‘Power dwells with cheerfulness,’ wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson. Though we often think of cheerfulness as the opposite of power, as an insincere urge to liven things up, Emerson knew it to be a resource of the self, a tool for shaping our emotional lives that can help to relocate us in the social world and link us to community. At the present time, as we confront wave after wave of bad news sweeping the planet, cheerfulness is worth our consideration.

With cheerfulness, we see a rise in emotional energy, a sudden uptick in mood. It is fleeting or ephemeral, in that it comes and goes. But we can control it. We can ‘cheer up’, just as we can ‘calm down’. As the English philosopher Robert Burton put it in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621): ‘expect a little … Cheer up.’ Burton’s advice to ‘expect a little’ reminds us that cheerfulness is a modest power. But, as Emerson knew, it is a power all the same.

Perhaps it is because of the modesty of cheerfulness that philosophers have largely overlooked it. They tend to focus on more dramatic emotions such as anger and melancholy, viewing human emotional life as a battleground of unconscious drives or overwhelming passions. The classic example of the man ruled by passion is the Greek hero Achilles. Overcome by his wrath toward Agamemnon, Achilles refused to join his fellow Greeks in the war against Troy, thereby betraying his own duty as Greece’s greatest warrior. Unlike wrath, cheerfulness is largely elective. We can manage it.

It is no accident that Burton mentions cheerfulness in a book about melancholy. In much writing about emotion, cheerfulness is presented as the antidote to the dark emotions of the melancholic. Medical thinkers up into the 19th century assumed that the human body was governed by the circulation of fluids, or humours. Melancholy, for example, arose from an excess of black bile, while certain stimulants were understood to counter melancholy and generate cheerfulness – one glass of wine (not two), bright music, a well-lit room. The Renaissance doctor Levinus Lemnius recommended good company, ‘dallying and kissing’, drink and dancing – all of which, he noted, generate an emotional uplift that endures for days afterwards, visible in the face. Other doctors argued that it was possible to stimulate cheer chemically: in 1696, the English doctor William Salmon prescribed a powder to stimulate cheerfulness: mix up some clove, basil, saffron, lemon peel, bits of ivory, leaves of gold and silver, with shavings from the heart of a stag and, voilà! – you will be made cheerful.

Whether or not anyone took these medical approaches to cheer seriously, it’s clear that cheerfulness is deeply linked to the body, and, in particular, the face. Indeed, it begins in the face and moves inward. As the French writer Germaine de Staël pointed out at the beginning of the 19th century, when you take on a cheerful expression, no matter what the state of your soul, your cheerfulness moves into the self: ‘the facial expression penetrates, bit by bit, what one experiences.’ The interior of the self is changed by the power of cheer.

This trajectory of cheerfulness through the self is linked to the history of the word ‘cheer’ itself. ‘Cheer’ comes from an Old French word that means, simply, ‘face’. The term comes into English and spreads through medieval culture in the 14th century. In Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1387-1400), for example, people are depicted as having a ‘piteous cheer’ or a ‘sober cheer’. ‘Cheer’ is an expression, but also a body part. It lies at the intersection of our emotions and physiognomy.

The individual doesn’t perform cheer; instead, it envelops him

In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation sparked intense debate over the meaning of spiritual community. At the same moment, when the Bible begins to be widely translated into vernacular languages, the simple noun ‘cheer’ expands to encompass the adjective ‘cheerful’ and, eventually, around 1530, includes the more abstract idea of ‘cheerful-ness’, which turns the local expression of the face into an abstract noun, something that can circulate as an emotional quality of the self. In the Geneva Bible (1560), from Saint Paul’s ‘Second Letter to the Corinthians’ we learn that to participate in the Christian community you must practise caritas, or love. ‘As every man wisheth in his heart,’ says Paul, ‘so let him give; not grudgingly, or of necessity, for God loveth a cheerful giver.’ God loveth a cheerful giver. These words resonated widely across the early modern world, linking cheer – and the face – to the practice of caritas, a social and religious activity.

Commentators on the Bible struggled to grasp the meaning of Paul’s famous phrase. Erasmus of Rotterdam, the greatest intellectual of the day, linked the cheerful body to community, saying: ‘let thy thankful gift be increased and doubled with a merry look and cheerfulness.’ Giving is good. But giving cheerfully is even better, and your intentions may be seen through your ‘merry look’. Conversely, if you are not cheerful (with no merry look), you may not be a true Christian. This was the suspicion held by John Calvin, the great Protestant reformer. He suggested that stingy or reluctant participation in the charitable Christian community is the mark of Catholics, whom he saw as decadent and fearful of papal authority, whereas good Christians give cheerfully, with a glad visage. A bit later, the poet and preacher John Donne extended this idea, noting in a sermon that God gives his holy word to us, ‘not in a sour, and sullen, and angry, and unacceptable way, but cheerfully’.

Modern readers might be struck in these early accounts by the extent to which cheerfulness is much more than the superficial performance of the upbeat colleague or the annoying salesman. A social quality, it shapes and defines a particular moral community. It emerges between people, binding them together. No wonder doctors sought to generate cheerfulness through chemical means.

During the European Enlightenment, as the great religious debates of the early modern period begin to wane in Europe, the theological dimension of cheerfulness falls away. Yet its essential social dimension remains, as the characteristic of enlightened gatherings. The 18th-century Scottish philosopher David Hume notes that cheerfulness is a force that is larger than the individual. The individual doesn’t perform cheer, as Calvin had suggested; instead, it envelops him. Anyone who has ever passed an evening with ‘serious melancholy people’, Hume points out, can surely acknowledge that, when a good-humoured or gay person enters the room, ‘cheerfulness carries great merit with it, and naturally conciliates the good will of mankind … others enter into the same humour, and catch the sentiment, by a contagion or natural sympathy.’ Cheerfulness is now a ‘contagion’. Elsewhere, Hume uses the metaphor of the flame to describe how cheerfulness might set a company alight.

If cheerfulness is healthy and social, even morally upright, we can understand why Emerson, with whom I began, understands it as a kind of power. Cheerfulness can condition our mood, but it also inflects our social being. It is essential to a healthy society. Whoever can control and harness it will possess a rare resource for shaping her emotional life and those of her fellows. For Emerson, the first great moral philosopher of the Americas, cheerfulness informs a well-lived life. It is also linked to creativity.

The cheerful sensibility brings the social vision of the moralist together with the creativity of the poet

In his essay ‘Shakespeare, or the Poet’ (1850), Emerson asserts that poetic genius requires two things. First, the ability of the poet to see natural phenomena as moral phenomena – that is, to turn things in the world into metaphors of our inner lives. It is the poet who first sees that apples and corn can mean something beyond their use as fruit and grain. The poet turns things into signs that convey ‘in all their natural history a certain mute commentary on human life’. Through the poet’s noticing, nature and humans are linked. No less important is a second trait: ‘I mean his cheerfulness, without which no man can be a poet – for beauty is his aim. He loves virtue, not for its obligation, but for its grace.’ The poet’s cheerfulness involves his ability to see the beauty of the world, to see things ‘for the lovely light that sparkles from them’.

Emerson’s celebration of the cheerful sensibility brings the social vision of the moralist together with the creativity of the poet. He suggests not only that cheerfulness links people together in communities, but that he who controls cheerfulness can remake the world. Cheerfulness is a psychological and emotional force, originating in vision and sensibility.

The turn of the 20th century saw a proliferation of what the philosopher William James called ‘mind-cure ’ movements – that is, approaches to living that assumed the influence of mental states on everyday productivity and social interaction. These movements swept cheerfulness along with them. The turn of the century ‘inspirational’ writer Orison Swett Marden, who founded SUCCESS magazine in 1897, placed cheerfulness at the centre of his thought. His many titles include Cheerfulness as a Life Power (1899), The Optimistic Life (or, in the Cheering-Up Business) (1907) and Thoughts about Cheerfulness (1910). Marden’s volumes are largely lists of ‘wise sayings’ and clichés about the advantages of being upbeat. These advantages are both personal and professional. They will make you happy – and help you make money.

In Cheerfulness as a Life Power, Marden calls cheerfulness ‘The Cure for Americanitis’. The book is laced with reflections on how hard Americans work, on how little time they have to enjoy themselves, on how materialistic they are. Marden’s goal is not only to get Americans to relax, but to get them to become more productive and wealthy. This miracle is to be achieved through the spread of cheerfulness.

About the same time, in 1911, the Boy Scouts of America published its first handbook, combining advice about such practical skills as how to build a fire in the woods, with moral encouragement toward a better life. The development of the self is governed by a ‘Scout Law’, consisting of 12 virtues. The eighth of these is cheerfulness. Here is how the Scouts define it:

Another scout virtue is cheerfulness. As the scout law intimates, he must never go about with a sulky air. He must always be bright and smiling … A bright face and a cheery word spread like sunshine from one to another.

Taking in a larger historical frame:

A good scout must be chivalrous. That is, he should be as manly as the knights or pioneers of old … He should be cheerful and seek self-improvement, and should make a career for himself.

With the 20th century’s expansion of consumer and mass experience, cheerfulness circulates as a concept that can bring capitalist ambition into phase with the ethical concerns of an earlier era. The Scouts’ emphasis on skills of woodcraft and survival are intended to prepare a new, mostly male, class of consumers and producers, each looking out for himself, for life in the rough world of the marketplace. Capitalism pits individuals against each other in a duel to the death for resources and money. It is a lonely business. Scout cheerfulness gives it a heroic cast. The external diffusion of cheerfulness will lead to professional success, as the salesman or junior executive brightens up the office. Actions that might appear self-serving or unctuous are recast as echoes of a more noble past. Each fledgling ‘organisation man’ – as the sociologist William Whyte put it in his 1956 management book – is, we learn, at heart, a wandering knight, if not a rugged trapper.

You’ve been fired in a corporate restructuring and are too old to be rehired … The solution is cheerfulness

Both Marden and the Scouts see cheerfulness not as a philosophical concept or theological idea, but as a tool. Stripped now of its roots in debates about community and charity, it can be deployed in daily life and generate specific rewards. These writers bring cheerfulness into the industrial age, where it is soon taken over by the huckster mentality. In the years following the Second World War, the clergyman Norman Vincent Peale made a fortune selling his own brand of ‘positive thinking’, which purported to lead even the most desperate and bereft to success and happiness. Peale’s work emerged from the psychic chaos of the war, as thousands of young people returning home were forced to adapt to a new economy, and transformed the social and theological cheerfulness of the Bible and the Enlightenment philosophers into a therapy for the man in the grey flannel suit.

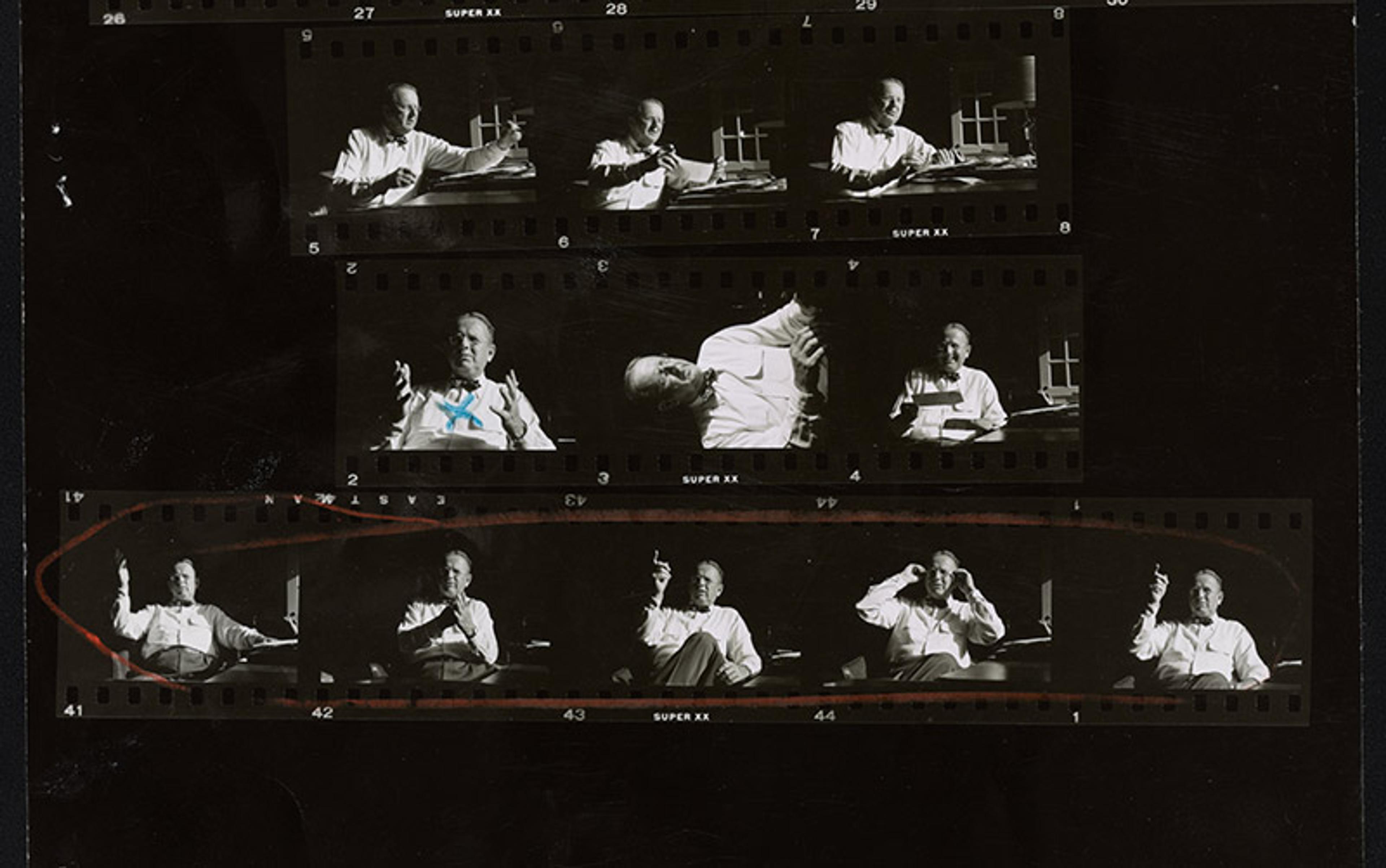

A contact sheet from a Look magazine assignment featuring Norman Vincent Peale in 1953. Courtesy the Library of Congress

Peale’s most famous book, The Power of Positive Thinking (1952), aims to mobilise the power of attitude for the goal of worldly success. It is built out of a set of exhortations, disguised as scientific truths, and intertwined with illustrative anecdotes. The anecdotes are particularly interesting, since they divide the world into actors and observers. The book is peopled by a shadowy group of unnamed persons, some of them uncomfortably strange: ‘I was on the stage greeting people when a man approached me … with a peculiar intensity of manner,’ recounts Peale. These people are miserable, and they come to Peale after his various speeches. Lonely, uncertain, they’ve been driven to seek new solutions for their problems. We watch as Peale consults with the many strangers who approach him out of nowhere. He consoles them (and us) with anecdotes about some of his close friends, who, unlike the shadowy sufferers who seek Peale’s help, are generally named; and all of them seem to be successful business people or media stars who seem to have gotten his message.

The uncertainties that trouble Peale’s sufferers are rooted in the massive corporate expansion of the postwar economy. It’s not just the memory of the recent war, and the possibility of trauma that lurks unacknowledged in the background, but Peale’s miserable clients often fear that they are undereducated, unprepared for challenges, or that they cannot conform to the cultures of their corporations. In other words, Peale is placing us right in the midst of a set of social transformations analogous to what we saw with the Boy Scouts, where an earlier, agrarian economy was refigured for the modern world via woodcraft. In Peale, we meet a class of workers in the midst of a new economy, for which they are spiritually and emotionally unprepared.

Peale is an easy target for criticism. His book is a transparent hodgepodge of clichés and fake anecdotes, presented through the sober ‘case study’ tone of the mid-century’s social sciences. But the larger implications of his description of the US malaise are worth noting. Peale’s answer to the misery of his subjects is to translate their objective dilemmas, rooted in economic uncertainty and a changing job market, into subjective problems. You are pathetic, not because you’ve been fired in a corporate restructuring and are too old to be rehired, but because you have the wrong attitude. The solution is cheerfulness.

The story of cheerfulness is bound up with the story of bodies, with how we inhabit our faces and gestures. But it is no less bound up with the story of communities. Both Peale and Boy Scout literatures build on the earlier language of cheerfulness as articulated in the Bible and in the work of early modern philosophy. But they strip it of its collective dimension. And as those communities are erased and reimagined in the developing world of industrial, and now post-industrial, capitalism, cheerfulness is at once endlessly evoked and drained of its power to bind humans to each other. Today, cheerfulness mainly evokes the ghosts of earlier cheerful scenes: we walk among the ruins of theological and natural cheer. Contemporary cheer – the gaiety of networking apps and cheer squads – mimics the spirituality of communities that no longer exist.

Good cheer won’t revolutionise the future, but it will render the present tolerable

Cheerfulness made its return to the public stage in March 2020, when the then president of the United States, an avowed disciple of Norman Vincent Peale, went on national television to promote a set of fake medications that he claimed could cure the sick and dying. When challenged by the press about his comments, the president took no responsibility but declared: ‘I am a cheerleader for America.’ Donald Trump sought to nationalise the power of cheerfulness, as if the horrors of the COVID-19 pandemic could be overcome through a better attitude. His own ignorance and deceit were now subsumed into a larger patriotic mission. Trump presented himself as the ultimate salesman: when he touted fake cures for the body, he was also selling an image of a nation for which he alone could speak. Such is the status of cheerfulness at the beginning of the 21st century. Whatever happens next, something has changed.

One consequence of life in the pandemic age is that it demands cheerfulness. The resilience of the virus and the endless drudgery it’s imposed on our daily lives have sapped optimism and eroded our ability to plan for the future. Cheerfulness offers a momentary, modest respite from a situation haunted by dread and confusion. We know that good cheer won’t revolutionise the future, but it will render the present tolerable, and bring us together in a time of isolation. It can even transform the impersonality of digital connection, making room for genuine, if often fleeting, expressions of community identity.

The pandemic, which cruelly mimics the Enlightenment celebration of conversational ‘contagion’ as the incubator of cheerfulness, imposes a reinvention of cheer. Hume’s idea of cheerful affect as a kind of fever that can transform the emotional tenor of a community is turned inside out. The mere practice of self-discipline, of social distancing and proper hygiene, becomes a reaffirmation of community: we can remain cheerful only because we do not contaminate, because we remain discrete. Not least, cheerfulness bridges the distance imposed on us by our fear of contamination. It can circulate because the disease does not.

So, from a distance, and despite digital mediation, cheerfulness may re-emerge, in expressions of care and concern, in offers of help from afar. These are only small gestures, but they are gestures nonetheless – like the Biblical practice of the ‘cheerful giver’. They imply care and empathy. Because we control and cultivate cheerfulness through our conversations – digital or otherwise – we recreate community through an act of the will.

Debased and overlooked, cheerfulness provides an instant of solace, a flash of support. Its vital usefulness emerges at moments of crisis. Beyond the commercialisation of our cheery culture and the fake gaiety of our politics, cheerfulness is a tool that frees us from our bonds by asserting affective freedom, often in the very face of oblivion. Even in its modern iteration, cheerfulness is a form of emotional power that should not be overlooked. It is not the ‘hope’ of the messianic, or the ‘optimism’ of the cheap politician. It makes more modest promises – to get you through the next few hours, to connect you to a neighbour. You can’t build a politics on it. But you probably can’t rebuild a world without it.