Fresh off a public breakdown after making antisemitic Tweets and threats, divorcing a Kardashian, and earning 60,000 votes standing for the US presidency, Ye (né Kanye West) is an intriguing figure in global pop culture. Nothing if not complex, he has won 21 Grammy awards for his music performances and productions while maintaining an ever-growing, and increasingly horrifying, hall of shame. Who can forget him interrupting Taylor Swift’s 2009 MTV Video Music Awards win with the now memetic phrase ‘Imma let you finish’, after which President Obama deemed him a ‘jackass’? Or West piping up in 2018 to claim that 400 years of slavery was a ‘choice’ that Black people made; or his assertion two years later that Harriet Tubman ‘never actually freed the slaves’; or his recently proclaimed appreciation for Adolf Hitler? What follows here isn’t a redemption arc: you can have great cultural insight and still be a bigot. That said, amid all the ‘White Lives Matter’ T-shirts and public performances of mental breakdown, West’s canny affinity for using food as a symbol for status in the United States has gone largely unnoticed.

In his catalogue of 11 studio albums, West includes more than 140 references to foods, drinks, cooking and eating. As Food Studies professors, we became interested in what he was trying to express through these references. Many of them namecheck brands West admires. There’s Grey Poupon (‘Yeezy, Yeezy, Yeezy, this is pure luxury/I give ’em Grey Poupon on a DJ Mustard, ah!’); Nobu restaurant and Whole Foods grocery (‘Huh? I swear my whole collection’s so cruise/I might walk in Nobu wit’ no shoes/“He just walked in Nobu like it was Whole Foods”’); also fast-food outlets (‘Beggars can’t be choosers, bitch, this ain’t Chipotle’ and ‘Closed on Sunday, you my Chick-fil-A’). The food rap that made the most impact on US popular culture, as measured by thousands of memes and tweets, comes from West’s track ‘I Am a God (Feat. God)’ on the album Yeezus (2013). To wit: ‘In a French-ass restaurant/Hurry up with my damn croissants.’

Expediency in service is only what a deity might expect – though many people on the internet could relate. The best of the memes superimpose West’s face over a croissant, or over concertgoers waving at him from the foot of a stage, pastries in hand. Others set him alongside Napoleon Bonaparte or the Pillsbury Doughboy. The memes caught the attention of W David Marx, a former editor at The Harvard Lampoon, who in 2013 wrote a satirical response on behalf of a fictitious ‘Association of French Bakers’ chiding West for failing to consider the time it takes to achieve excellence in boulangerie. Marx’s letter, posted on Medium, went viral, and was picked up by Time magazine and USA Today, and prompted subsequent apologies for mistaking Marx’s parody for fact. ‘The Association of French Bakers does not exist,’ wrote Alexander Aciman in Time.

Yet mocking West is too easy. He is, after all, a contemporary cultural provocateur. The implicit logic of those meme-makers and critics, bent on turning his rap into a joke on its creator, suggests they took West at face value, as if he were merely complaining that an American Black man in a French restaurant doesn’t belong or is somehow out of place. But West was, in essence, exposing a politics of food consumption that, in tying French food to class status in the US, and concerning itself only with dominant Eurocentric and colonial foodways, silences the labours of indigenous chefs, chefs of colour and queer chefs. There’s powerful evidence that French food still aligns with class – which in the US can never be separated from race. So, when West tsks about French-ass restaurants, he reminds us that such covert forces of class allegiance persist, and that they need critiquing.

West may or may not have visited Thomas Jefferson’s neoclassical plantation Monticello, in Charlottesville, Virginia. But, there, historical tourism nuts can purchase Dining at Monticello (2005), a 200-page tome that catalogues the foods and wines that Jefferson brought back to the US when he served as minister to France. It includes Jefferson’s handwritten recipe for Biscuit de Savoie, a cake created in 1358 in honour of the Holy Roman Emperor. The recipe may be in Jefferson’s handwriting, but Jefferson did not work in his own kitchen. His meals at Monticello, and later in the White House, were prepared by the enslaved James Hemings, who had been the property of Jefferson since he was eight, and who was brought to Paris for the purpose of serving his master.

Hemings had been the property of Jefferson’s father-in-law, who was also Hemings’s father – making him the half-brother of Jefferson’s wife, Martha. And Hemings was the older brother of Sally Hemings, who also travelled to France under Jefferson’s direction and later bore at least six of Jefferson’s children. It must be said of this complicated family tree and its attendant power dynamics that consent would be impossible, as enslaved women had no legal protections against unwanted sexual advances. It is also true that James Hemings, an enslaved Black man, was the first American on record to train as a chef in France. It was his work, meeting Jefferson’s insistence on the excellence of French cuisine, that set into motion the attitudes Kanye West had in his target – namely, that a French restaurant is where classy things happen.

Despite recent efforts of people inside and outside the restaurant business to make room for more chefs of colour, more female chefs, and more acknowledgment of the excellence of cuisines once deemed too ‘exotic’ to be mainstream, French dominance of the US culinary imagination in terms of high-end, high-class dining endures. Instagram reels and TikTok feeds show that posting images of oneself eating French food and, even better, eating French food in France, indexes social status. Next to predictable tourist shots of an ice-cream cone held aloft in front of the legendary Berthillon Glacier on Paris’s Île Saint-Louis, or a fork dipping into the steak tartare at Brasserie Lipp – which featured prominently in Ernest Hemingway’s posthumous memoir A Moveable Feast (1964) – foodie influencers such as ‘312 Craves’ share #frenchfood from fashionable hotspots around the US. In our Food Studies courses, there’s always a student or two eager to tell us of the magic of French baguettes, discovered while studying abroad, and who note that ‘over there, flour is less processed.’ (They happen to be right.) Like other students across the US, many of ours have binge-watched the TV fantasy Emily in Paris (2020-), which dominated quarantine-era viewing by fetishising brasseries, Champagne and omelettes au fromage. Even if the beret-sporting Emily is as clichéd as driving a Citroën 2CV, there is a measure of charm in her observing, with more than a dollop of romantic homage, that ‘The entire city looks like Ratatouille.’

Emily in Paris. Courtesy Netflix

This reification of French food by US media merely highlights how, in a country that recently crowned the burrito bowl the most popular dish (followed by the trusty burger), French cuisine is still the epitome of high culture. As Nikita Richardson, senior staff editor for The New York Times food section, put it: ‘We just can’t quit the French.’

It turns out that there are reasons for this that even Jefferson cannot claim. They have to do with how ‘French cuisine’ came into being and, most importantly, became canonised. Of course, French people ate ‘French food’ before the French Revolution, but there was no such thing as a ‘French chef’ for anyone but the noble courts before 1789. Prior to that, Paris was home to fewer than 50 taverns meant for common travellers. The aristocracy entertained on their own estates, courtesy of their cook-servants. Sofia Coppola’s film Marie Antoinette (2006), set in the final years of the Ancien Régime, imagines the high-end fare that the queen consumed in a montage scene showing Marie and her court snacking on dozens of platters of cakes and confections – pink macarons, bite-sized redcurrant tarts and strawberry ladyfingers decorated with edible pink flowers. This was a time when peasants (imagine Marie’s chambermaid) ate mostly bread – not brioche made with eggs and milk, as Marie got, but dense loaves made with the far cheaper barley, oats and buckwheat. It’s no wonder that the ensuing grain shortage was a major cause for the revolution.

In a stroke of branding genius, the chef was canny enough to include a portrait of himself in his book

One toppled monarchy, a new constitution and 30 years later, there were approximately 3,000 restaurants serving as many as 100,000 Parisians per day. These establishments entertained a new class of Parisian, who had a little money and a lot of ambition. Around this time, the world’s first celebrity chef was enjoying success in his career. Marie-Antoine Carême came from a very large, very poor Parisian family; by age 10, he was on his own, illiterate and broke. To sustain himself, he signed a six-year contract to wash dishes at a tavern called Fricassée de Lapin, on the edge of Paris. By 16, he’d landed a job at a pastry shop near the Palais-Royal.

Carême blossomed under his new boss, who recognised his talent and encouraged him to learn to read and write. Young Carême spent his free hours in the library, poring over architectural drawings, then returning to the shop to reproduce them in sugar and pastry. The boss began marketing Carême’s creations as banquet centrepieces, and within two years Carême had amassed such a following that Bishop Talleyrand, Napoleon’s chief diplomat, hired him to work under his personal chef – a landing spot that allowed Carême to meet other cooks of royal regimes.

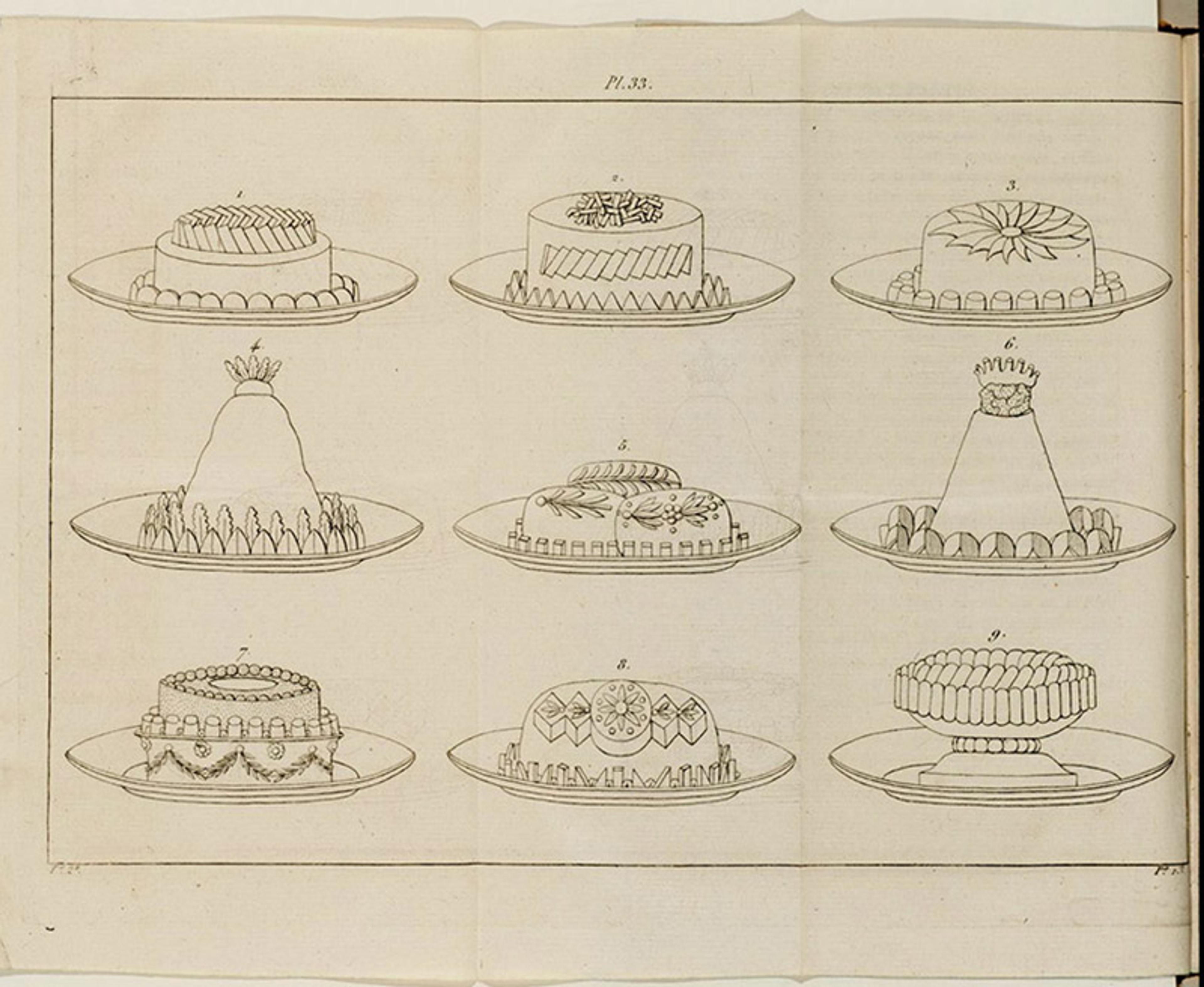

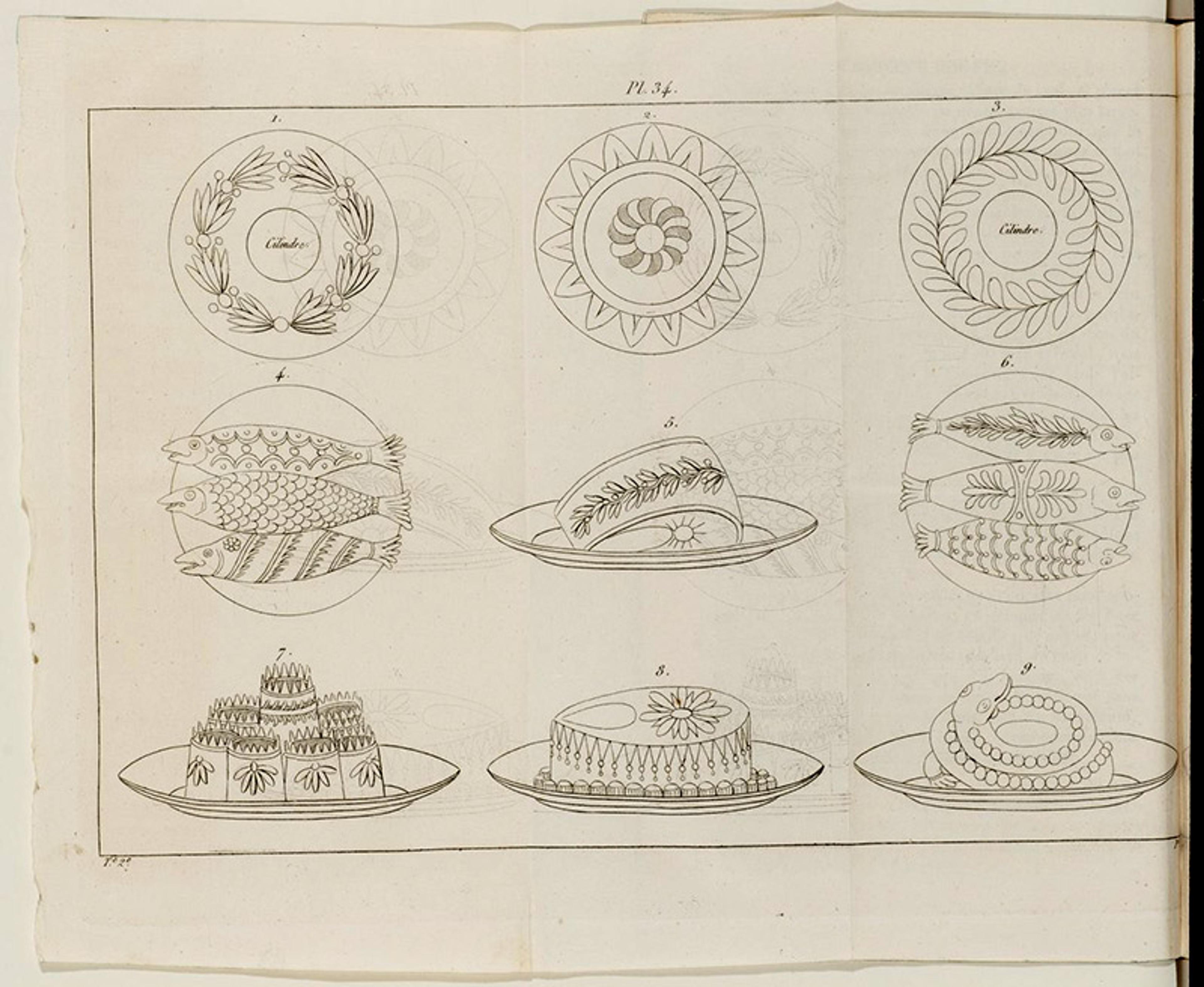

From Le pâtissier royal parisien (1815) by Marie-Antoine Carême.

Images courtesy the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

In 1815, Carême left Paris to work in London, as head chef for George, Prince of Wales. He stayed three years, during which he wrote his first book, Le pâtissier royal parisien, a 482-page manual with sweet and savoury recipes and accompanying schematic line drawings. Published in 1834, the introduction is nothing short of prophetic:

This work … will throw additional lustre on our national cookery so long and so justly esteemed by foreigners … attributed to the well-known fact that our modern cookery has become the model of whatever is really beautiful in the culinary art … and the art of French cookery, as practised in the 19th century, will be the pattern for future ages.

In many ways, Carême was born at the right time. Post-revolution France was flourishing economically, creating conditions that allowed restaurants to cultivate ‘regulars’ who could afford to eat out often. Another change was technological: the printing press meant Carême’s recipes and drawings could be mass produced on the cheap. And, in a stroke of branding genius, the chef was canny enough to include a portrait of himself in his book, which helped cement him as an authority of record – and helped cement French cuisine as an important subject.

Carême’s archive established the very basis of French cuisine – the ‘mother sauces’, mutable formulas that, with the entry-level know-how, create the architectural foundations of a multitude of dishes. That these sauces – béchamel, velouté, Espagnole, and tomato (Hollandaise was included a few years later) – were the invention of, among others, an 18th-century chef named François Pierre La Varenne mattered less than that they were inscribed authoritatively by Carême. In time, his cookbooks became more than guides: the food historian Alan Davidson described Carême’s mother sauces as ‘an intellectual platform for cooks to redefine their professional status’, because they broke down complex practices into practical steps and in the process became canonical. (Incidentally, ‘mother’ is also the word used for the moulds necessary to make many beloved French cheeses, including brie and Comté, as well as the term for the biofilm composed of cellulose, yeast and probiotic-dense bacteria that develops on fermenting liquids such as vinegar.)

No one helped spread the world of the canon more than Auguste Escoffier, who, in the decades following Carême’s career cooking for the nobility, focused on improving everyday restaurant experiences. Escoffier was born in a village on the outskirts of Nice in 1846, where, as a teenager, he apprenticed in his uncle’s restaurant, and later reported that he was often bullied. At the time, cooking was not a profession held in high social regard: it was a hot, thankless job that typically involved disordered workspaces and even uncleanliness. Young Escoffier was drafted into the army, where he became enamoured of the military brigade system, the adoption of which changed not only his life but the lives of millions of future restaurant workers.

In keeping with this military brigade system, Escoffier reorganised the canteen kitchen according to a chain of command, with the chef as ‘the general’ directing the campaign and various sub-stations flowing from his own, each with its own commander. Escoffier’s hierarchy professionalised the atmosphere of the kitchen, and many food scholars argue that its emphasis on hygiene and teamwork produced a new pride in the profession. In 1890, Escoffier formed a partnership with the Swiss hotelier César Ritz. Their first joint project was the Savoy Hotel in London, and their goal was to transform it into the place in the world to experience culinary excellence. From there, they moved to the Ritz Hotel in Paris, then the Carlton Hotel in London, repeating a pattern of setting up chains of command in the kitchens (in the process, they were also convicted of fraud in the form of taking kickbacks from restaurant suppliers, a reputational stain each managed to overcome). While managing smart hotel dining, Escoffier advocated a system in which the food comes out of the kitchen as the guest requests it, in the order in which it should be eaten – this was his idea of meal pacing. He also partnered with Cunard, consulting with chefs on menus for their luxury ships, thereby ensuring that French food was what the international set should demand. Escoffier was also prolific, writing more than 5,000 recipes; even today, his book Le guide culinaire (1903) remains a bible for students enrolled in cooking schools around the world.

Into every kitchen Escoffier entered, the mother sauces and the brigade system followed, opening up the pleasures of French cuisine to the world, but also putting them into a kind of coffin. Every canon has its drawbacks: by nature, it is fixed. Yet despite its rigidity, the French culinary canon allows for homage and suggests that tribute itself is a kind of innovation.

Legions of American women were willing to undertake such ardours for social status

Enter Julia Child, who in the mid-20th century singlehandedly and successfully promoted middle-class American interest in French cuisine. Child was a native Californian, who trained in the finishing-school style of Le Cordon Bleu and was equipped with a flair for communicating her passion. Her two-volume book Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961, 1970) demonstrated that the many strictures of French food were accessible to home cooks in the US. Having fallen for the French reverence for food after following her husband to Paris, Child believed she could ‘translate’ its pleasures to Americans and improve their lives in the process. Thanks to the post-Second World War economic boom, the average US consumer had money to spend and a social ladder to climb. Child’s cooking show The French Chef, which aired on Boston public television in 1962 and then nationally for the next 10 years, demystified Carême and Escoffier while creating room for failure: ‘Always remember: if you’re alone in the kitchen and you drop the lamb, you can always just pick it up. Who’s going to know?’ she told viewers, in the signature warbly high voice that made her caricature-fodder for comedy impresarios, as well as a national treasure.

Child’s teachings nonetheless came with a cost. The culinary historian Betty Fussell describes her own slavish adherence to the formulas that Child popularised as an exercise in which she ‘spent time and money mastering the art of competitive cooking’. She spoke for legions of American women who were willing to undertake such ardours for social status. And yet Child’s influence endures. Her roast chicken recipe is an American classic – reprinted time and again in newspapers, and a staple of instructional YouTube videos and TikTok feeds – while her stuffed eggplant has become a culinary litmus test for aspiring cooks. The food journalist Alan Richman compared the fiddly task of preparing mushrooms for the aubergines’ stuffing to ‘drying laundry by hand’. Only the most dedicated of cooks would bother perfecting it.

At the same time, Child herself became an American classic, so thoroughly representing the relationship between French food and social aspiration that when Dan Aykroyd sent her up in a Saturday Night Live skit in 1978, audiences across the US knew very well that he was mocking the fancy Frenchified aspirations of an entire nation.

One of the more unusual outings for Escoffier’s brigade system in recent years was Disney-Pixar’s animated movie Ratatouille (2007) – a favourite pop-cultural amuse-bouche among our Food Studies students – a familiar bildungsroman set in the context of a French culinary fantasy. The film’s plot follows Remy, a gutter rat who dreams of becoming a chef. Who can forget Remy attempting to smoke a mushroom on a spit over an old woman’s rooftop chimney, only to be struck by lightning that causes his mushroom to puff up like a popcorn kernel? Upon tasting the result, Remy pronounces it to contain an ‘mmmm ZAP’ of flavour with ‘lightning-y’ tang. Yet to become a ‘real’ chef, Remy must mask his identity and hide under the toque of his marionette-like kitchen accomplice, Alfredo Linguini, yanking his hair to operate the man’s arms through each dice and stir. As Remy finds glory cooking at Gusteau’s, the premiere restaurant in Paris, he epitomises the film’s central adage: ‘Anyone can cook.’

The fancy mustard from Dijon, breakfasting on croissants – all of this is symbolically off-bounds to minorities

That Ratatouille is animated tends to obscure the direct reference to Escoffier’s brigade and, more importantly, the realistic labour issues at play in high-end kitchens where so few women are employed. The only female character in the film, Gusteau’s rôtisseur Colette Tatou, explains to Linguini that ‘haute cuisine is an antiquated hierarchy built upon rules written by stupid old men, rules designed to make it impossible for women to enter this world. But still, I’m here!’ Colette’s gender struggles make explicit the tensions in the rat’s own quest for acceptance as a chef in a French kitchen, labouring his way through the embedded hierarchies of the brigade system.

In the climactic scene, Remy prepares a ratatouille that wins the heart of the film’s antagonist, the critic Anton Ego, showing that even a simple Provençal preparation – created by a gnarly rodent, at that – can be the apex of good taste. The premise, absurd yet heartwarming, makes it (like Julia Child) ripe for parody. In the awardwinning film Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), set in a multiverse uncomfortably close to our own, the lead character visits a Benihana-style teppanyaki joint, and encounters ‘Raccacoonie’ when she runs into a wild-eyed chef who has a furry ringed tail sticking out of his toque.

Having come full circle, from pop culture to the French Revolution and back again, we now find homages to French cuisine across the rap music scene. Since Das EFX’s album Dead Serious (1992) made a reference to the French brand Grey Poupon on their track ‘East Coast’ (‘He’s the don, have you seen my Grey Poupon? Bust this, we roll more spliffs than Cheech and Chong’), waves of rappers have invoked the mustard to signal class status. When Kanye West demands that his server hurry up with his croissants, his point is not merely to acknowledge that many Americans align French food culture with status, but to highlight the way such alignments are traditionally closed off to Black people. In his US, ‘French’ equates socioeconomic status with white privilege: the fancy mustard from Dijon, dining in a ‘French-ass restaurant’, breakfasting on croissants – all of this is symbolically off-bounds to minorities. So, when West demands the expedient delivery of his pastry, he effectively yokes the cachet of French cuisine in the US to the standpoint of a Black man from Chicago who has achieved such regular access to it that he can take it down. Perhaps too, in West’s ‘hurry up’, there is a nod to the invisible violence that permeates French restaurants through the brigade system whose structure remains intact in so many high-end eating places today.

For all its whimsical Disneyfication in Ratatouille, the degree of bullying in the kitchen brigade – which, ironically, Escoffier designed his system to mitigate – remains unchanged. Kitchen staff are as notoriously overworked and underpaid as ever they were. There’s no better representation of this kitchen exploitation on the screen today than the TV drama The Bear (2022-). Its portrait of a tortured chef who flees his job at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Manhattan to take over his family’s Chicago beef joint amid a crisis reveals the worst kind of abuse the brigades are famous for. ‘You are terrible at this, you are no good at it,’ the head chef hisses in a flashback scene – as our guy tries his best to concentrate on arranging tiny sprigs of fennel and orbs of fish roe atop a bite-sized sliver of grapefruit-pink salmon – silencing a thrumming kitchen staffed with sauciers, chefs de partie and cooks of all ranks. The scene is shockingly brutal, but also shockingly complicit, co-opting viewers who fundamentally believe that the French brigade system produces the most aesthetically perfect food that exists. The intensity of the scene culminates in the top chef practically spitting into his underling’s face: ‘You should be dead.’ It’s so off the charts that it tips into dark comedy. Still, the real message here is that life in the classic brigade system involves routine abuse.

Why is this important? Because it asks us to consider how our experiences with food give us a sense of value and confer social membership. The Bear hit home at the same moment as the TV docuseries High on the Hog (2021-), which traces the lineage of many so-called American foods to Africa, and also spotlights Black culinary expertise, won a prestigious Peabody award for excellence in storytelling and was hailed by The New York Times as ‘profound[ly] significant’. The uneasy coexistence of these two shows hints that Americans value French food as a symbol of class even as we know that our own nation’s history obscures the real foodways upon which the shaky concept of ‘American food’ rests. The US chef Alice Waters made some attempt to bridge that distance by harnessing locally grown fresh ingredients to promote a vibrant simplicity in place of complicated and time-consuming preparations. Her ‘revolution’ at the restaurant Chez Panisse in California nearly rendered the ‘mother sauces’ obsolete. By the 1980s, Chez Panisse was known across the country for its French-American hybridity, and its success snowballed into the now absurdly popular farm-to-table movement.

The Birkin bag and Chanel No 5 – both evidence of the American desire for status in a French-inflected form

At the time, it felt as if French cuisine would be relegated to libraries. So how did it come roaring back? It turns out that it never really went away. Decades of its perceived cultural supremacy meant that its social signifiers remained embedded in the US collective understanding of class, which is what Kanye West plays to so well in his work. When he demands that kitchen servers hustle with his croissants, he insists that he’s worthy of occupying a space once reserved for those at the top of the social order. ‘I belong here,’ he says. Mobilising the trope of a ‘French-ass’ restaurant being a space – if not the space – by which class legitimises itself, West’s mocking term skewers traditional French elitism by aligning it with another cultural totem – another piece of bling. His meaning is less about ‘I’ll have some of that’ and more about ‘Look at you with your fancy props and pretensions.’ That French food sits outside of US ritual food traditions (Fourth of July barbecues, Thanksgiving and Labor Day picnics) makes it ever riper for a takedown.

Of course, other French products exert a serious hold on the aspirational ideals of modern Americans. There’s the enduring appeal of the Birkin bag, and the seductive status of Chanel No 5 – both evidence of the American desire for status in a French-inflected form. Both products are tied to distinct brand histories and traditions designed to appeal to outsiders like us; buying into them, according to this logic, will make us insiders. Like French cuisine itself, these overdetermined luxuries rely on a sense of exclusionary appeal, on the fact that you can’t get real versions of them elsewhere. This trope plays well with Americans who have grown up on the ubiquity of KFC and McDonald’s – places where it takes so little time for customers to get food that robots are now being installed to do the job. When West says ‘hurry up with my damn croissants’, he might as well be talking to one of them. And that’s why he says it. He’s saying that the so-called fancy treats are just as good as the ones we’ve already got. And on this point, a most unlikely person would have agreed. For Julia Child’s guilty pleasure was a McDonald’s French fry.