Parwati Soepangat (1932-2016), fondly known as ‘Ibu Parwati’ to the Indonesian Buddhist community, was one of the first women disciples of Ashin Jinarakkhita (1923-2002). Ashin Jinarakkhita was the so-called father of modern Indonesian Buddhism – and a prominent founding member of the Indonesian Buddhayāna movement. When I arrived in Indonesia in 2015 to conduct research on Ashin Jinarakkhita, I learned about Parwati’s writings and role as a Buddhist missionary in the world’s largest Muslim country. One of my informants, a niece of Ashin Jinarakkhita, told me: ‘To understand Ashin Jinarakkhita and his Buddhayāna movement, you must talk to Ibu Parwati.’ So I met Parwati in Bandung and interviewed her several times at her home in Jakarta.

Parwati candidly shared many insights into Ashin Jinarakkhita’s Buddhayāna movement and the development of Buddhism during Indonesia’s New Order period (1966-98) under the president Suharto. The authoritarian New Order regime, which mainly focused on economic development and maintained a repressive approach toward Left-wing views and political dissent, lasted until Suharto’s resignation in 1998. Parwati shared her views on religion and gender issues too. In 1973, Parwati, with endorsement from Ashin Jinarakkhita, established and served as the founding chairwoman of the Indonesian Buddhist Women’s Fellowship, a women’s organisation within the Buddhayāna movement, about which we will learn more later.

The author with Parwati Soepangat, 23 March 2015. Photo by the author

According to the 2020 Indonesian national census, Buddhists make up approximately 0.7 per cent (around 2 million) of the total population in the world’s largest Muslim country. Today, many Indonesian Buddhists remember Parwati as the ‘Buddhist Heroine of Solo’ (Srikandi Buddhis dari Solo). Her life and career, in some ways, reflect the story of Buddhist women in postcolonial Indonesia. The Theravāda Buddhist-majority mainland Southeast Asian countries (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Thailand), have a strong patriarchal, monastic Buddhist tradition. However, no such patriarchal monastic authority for Buddhism exists in Islamic Indonesia. This provided the space and opportunity for Parwati to rise to prominence in the Indonesian Buddhayāna movement. Parwati was a double minority – a Buddhist and a woman – in Muslim-majority Indonesia. Nonetheless, she advocated gender equality and women’s empowerment to spread Buddhist teachings and expand women’s religious participation across Indonesia.

Parwati was born on 1 May 1932, in the Surakarta Palace of Central Java, which was then part of the colonial Dutch East Indies. Her Javanese parents named her ‘Parwati’ after the Hindu Goddess of power and beauty. Her father Kanjeng Raden Tumenggung Widyonagoro was a regent of the Surakarta Palace, the royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the Surakarta Sunanate. Her mother Raden Ajeng Soewiyah was a teacher in the palace school. Parwati’s biographer, Heru Suherman Lim, writes that she followed her parents’ Buddhist faith and adopted a vegetarian diet in childhood.

Born and raised in the Surakarta Palace, Parwati was educated and trained in Javanese traditions. She spoke Javanese while growing up, which later proved to be useful in spreading Buddhism among the Javanese population. As part of her traditional aristocratic training, she learned to put on kain kebaya, a jacket-blouse and batik skirt combination considered the national dress for Indonesian women, whenever she was out on palace grounds. She also fasted on Mondays and Thursdays, and sometimes ate only white rice and fruits to restrain her desire and practise self-discipline. Her biographer writes that, once a month, she slept under a sapodilla tree accompanied by her nursemaid to train herself to ‘accept unpleasantness and to develop a bond with nature.’ Parwati learned and enjoyed bedhaya, a form of Javanese ritual dance. She shared how she struggled to understand the meaning and philosophy behind the hand and leg coordination movements of the ritual dance, and how her knowledge in Buddhist doctrine helped her to achieve discipline and meditativeness.

Formal Dutch colonial rule of Indonesia ended in 1949, and national liberation soon brought the rise of a women’s movement and the emergence of women’s organisations. The call for education dominated the early phase of women’s activism. And Parwati was uniquely placed to contribute to this movement.

The roots of Parwati’s feminism came from her mother, Raden Ajeng Soewiyah. The latter was a palace teacher and shaped her daughter’s education and her feminism. Raden Ajeng Soewiyah – a keen reader of the works of Raden Adjeng Kartini (1879-1904), Indonesia’s first feminist and educator – wanted her daughter to study abroad to receive a higher education than she had. As such, Parwati received an excellent education from a very young age. After graduating from high school, she was accepted into Gadjah Mada University, a top university in Yogyakarta, at a time when it was rare for women to attend. In 1958, she graduated with a degree in educational psychology.

Javanese women did not achieve emancipation because of the view that the wife is inferior to the husband

After Parwati completed her college degree, her mother sought to send her daughter abroad to further her education. Raden Ajeng Soewiyah felt insulted by her friends who had suggested marrying Parwati to a man in the diplomatic service before sending her abroad. Her mother rejected her friends’ recommendations and insisted on sending her daughter overseas as an ‘unmarried woman’. A year later, Parwati enrolled in the George Peabody College for Teachers, which is now part of Vanderbilt University in Nashville in the United States, where she graduated with a master’s degree.

Upon completing her master’s in 1959, Parwati returned to Indonesia. She began her academic career as a lecturer in psychology at Gadjah Mada University. Following her marriage to Soepangat Soemarto (1932-2017), a professor of engineering at the Bandung Institute of Technology, she relocated to Bandung to become a professor in the faculty of psychology at Padjadjaran University. Between 1969 and 1970, when Parwati accompanied her husband to the University of California, Berkeley, for his graduate studies, she took courses in psychology there.

In 1986, back at Padjadjaran University in West Java, Parwati completed her doctoral degree in psychology with a dissertation entitled ‘The Influence of Cultural Environment on Motherhood and Emancipation as a form of Female Self-Actualisation: Case Studies of Working Mothers in Several Cities in Java: An Approach through the Theory of Cultural Psychology’. Drawing on case studies of working mothers in several cities across Java, she argued that Javanese women did not achieve complete emancipation because of the conservative view that the wife is inferior to the husband. This perception led them to take up an unequal share of household labour. Her dissertation combined interests in psychology, gender studies, and her knowledge of Javanese culture.

Parwati then served as the chair of the educational psychology department and as the director of the Centre for Women’s Studies at Padjadjaran University. She lectured at several institutions in Bandung, including the faculty of psychology at Maranatha Christian University, the faculty of philosophy at Parahyangan Catholic University, and the department of nursing at the School of Health Sciences Saint Borromeus. She also spoke widely at international conferences on psychology, gender, feminist theology and Buddhist studies.

Parwati told me in our interview that she knew little about Buddhist doctrines in her earlier years. During the early years of postcolonial Indonesia, most Buddhists were ethnic Chinese who worshipped in Chinese temples, known as klenteng. These temples fused elements of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism. Ashin Jinarakkhita, an ethnic Chinese Indonesian, first encountered Buddhism at Chinese temples through chanting scriptures and practising vegetarianism. Back then, most of the Chinese migrant monks in those temples were ritual specialists who performed funeral rites. They neither conducted religious classes nor lectured on the Buddhist teachings.

Unlike Ashin Jinarakkhita, Parwati was an ethnic Javanese who could understand neither Mandarin nor Chinese dialect. She could not further her knowledge of Buddhism at the Chinese temples. Instead, she learned about Buddhism at the Theosophical Society.

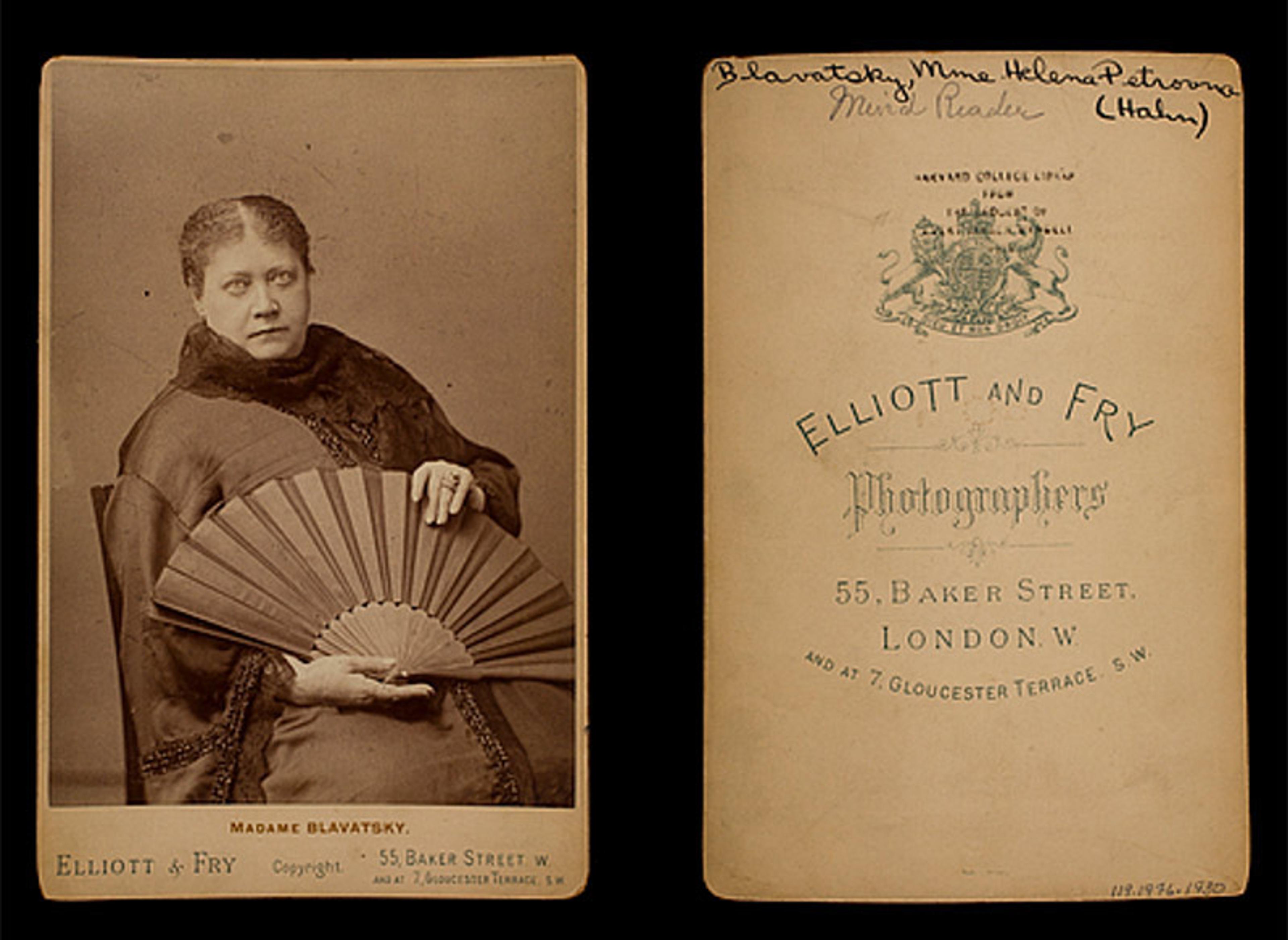

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky photographed by Elliot and Fry, London, May 1887. Courtesy Harvard Divinity School Library

The Theosophical Society was established in New York in November 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge, and others. In the 1880s, a German by the name of Baron von Tengnagell founded a branch of the Theosophical Society in the Dutch East Indies. However, little is known about von Tengnagell except that he died in Bogor in 1893, and the Theosophical Society declined following his death. A few years later, several Dutch and Javanese intellectuals revived the Theosophical Society and opened lodges in various parts of Java.

They wanted to dissociate Buddhism from Chinese culture and present it as an indigenous Indonesian religion

In the decades following national independence, the Theosophical Society promoted the teachings of major world religions, including Buddhism, to the general public, and garnered a wide following of educated Indonesians. Parwati became a member of the Theosophical Society when she was an undergraduate at Gadjah Mada University and began to learn about Buddhist teachings from Theosophical writings such as Olcott’s books The Buddhist Catechism (1881) and The Life of the Buddha and Its Lessons (1912). She often attended lectures and gatherings at various lodges in Java. At these lectures, she met Tee Boan An, who would later be ordained as Ashin Jinarakkhita, and Soepangat Soemarto, her future husband. The three soon became close friends due to their shared interests in Buddhism.

The Indonesian Buddhist community saw Ashin Jinarakkhita as a spiritual leader who, as Parwati told me, managed to revive Buddhism, which had disappeared in Indonesia. Ashin Jinarakkhita and his followers drew on historical claims to justify the propagation of Buddhism in the Muslim-majority country. They wanted to dissociate Buddhism from Chinese culture and present it as an indigenous Indonesian religion compatible with modern Indonesia. Ashin Jinarakkhita’s Buddhayāna movement stressed that diverse Buddhist sects and doctrines lead to a ‘single path’ (ekayāna) to enlightenment. His grand vision for a Buddhayāna movement was to promote an ‘Indonesian Buddhism’ for a culturally and linguistically diverse Indonesia.

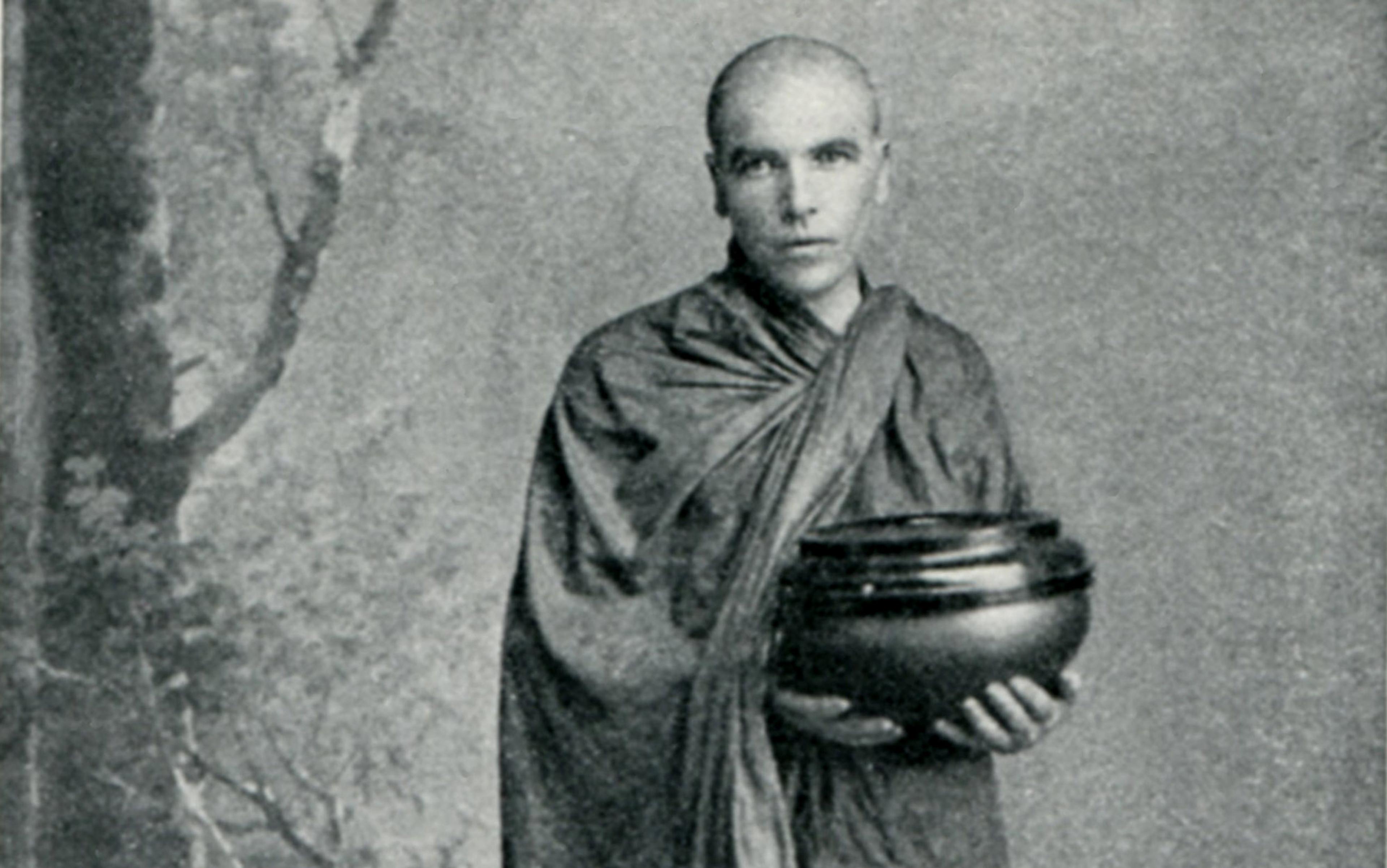

In 1955, Ashin Jinarakkhita returned to Indonesia from higher ordination in Burma. He and his disciples made two ‘dharma tours’ to urban and rural parts of Java, Sulawesi and Bali to spread the Buddhist teachings. Ashin Jinarakkhita wanted to convert native Indonesians to Buddhism. Therefore, he appointed Parwati, an ethnic Javanese, to serve as his Javanese-language translator for his missionary trips. They wanted to show that Buddhism was not a religion just for the Chinese population of Indonesia.

As the Buddhayāna movement grew, Ashin Jinarakkhita moved to establish an institution to organise its members. In July 1955, he established Indonesia’s first lay Buddhist organisation, the Indonesian Fraternity of Lay Buddhists (Persaudaraan Upasaka Upasika Indonesia, hereafter PUUI), to consolidate his lay disciples and train lay preachers to help him spread the dharma. The PUUI became an important platform for Ashin Jinarakkhita to ordain his senior disciples with the best knowledge of the Buddha dharma as lay preachers, known as pandita, to serve the needs of a growing congregation. Parwati was among the first disciples to be ordained as a pandita and was authorised to lead Buddhist funeral ceremonies, bless weddings, and deliver dharma lectures in various parts of Indonesia.

In the 1950s, the poor transport systems in Indonesia made it hard for Ashin Jinarakkhita to travel from one place to another and reach his growing number of followers. In the absence of a patriarchal Theravāda monastic authority and given the lack of monastic members to lead the congregation, panditas such as Parwati supported Ashin Jinarakkhita in ministering to the congregation and made it possible for the Buddhayāna movement to grow quickly within the span of a few years.

Parwati considers the Buddha’s stepmother as the first feminist Buddhist theologian

Ashin Jinarakkhita soon recognised the necessity of establishing a sangha (or monastic) organisation to represent the Buddhist community in Indonesia. On 23 January 1963, he founded the Maha Sangha Indonesia in Bandung. Shortly after the founding of Maha Sangha Indonesia, Ashin Jinarakkhita also decided to ordain the first Buddhist nun in Indonesia. During the early 1960s, bhikkhunī ordination (that is, the full ordination of a female monastic) in the Theravāda tradition was unheard of, and it remains a point of contention among the Theravādin communities in contemporary Southeast Asia. However, as bhikkhunī ordination is a common practice in Mahāyāna Buddhism, Ashin Jinarakkhita did not hesitate to support the ordination of nuns in Indonesia.

Following this first bhikkhunī ordination, Ashin Jinarakkhita encouraged Parwati to form a laywomen’s organisation within the Buddhayāna movement to complement the PUUI. On 14 July 1973, Parwati established the Indonesian Buddhist Women’s Fellowship (Wanita Buddhis Indonesia, hereafter WBI) and served as the founding chairwoman, with Sujata Gunadharma and Visakha Gunadharma as her deputies. The laywomen organisation had two aims. The first was to become the largest and most active Buddhist women’s organisation in Indonesia in terms of management, territorial coverage, membership, and range of activities to support women activists to elevate the status of women in Indonesia. The second was to nurture Buddhist women’s potential and guide them according to the dharma by adhering to the Buddhayāna values of inclusivism, pluralism, universalism and non-sectarianism.

In 1976, WBI expanded and relocated to Bandung, where the Maha Sangha Indonesia was based, to better coordinate the local chapters in 18 provinces all over Indonesia. As the chairwoman of WBI, Parwati took a proactive role in advancing the status of women in the Indonesian Buddhayāna movement and the Buddhist community at large. She considers Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī, the Buddha’s stepmother, as the first feminist Buddhist theologian in Buddhist history.

Parwati argues that the bhikkhunī order was the first women’s organisation in the world and was founded by none other than the Śākyamuni Buddha himself. She writes that the establishment of the bhikkhunī order provided an opportunity for women to pursue a spiritual life and elevated the position of women in a male-dominated society. Thanks to Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī, as she contends, women were no longer oppressed as ‘objects of worldly fulfilment’, and had opportunities to serve as religious teachers and achieve spiritual perfection.

Parwati also suggests that there were already Buddhist nuns in the Hindu-Buddhist kingdom of Srivijaya during the 8th century. Like Ashin Jinarakkhita, Parwati drew on historical claims to justify the propagation of Buddhism and, more importantly, to elevate the status of Buddhist women in the Muslim-majority country. More crucially, this allowed her to legitimise her WBI missionary campaigns to convert native, especially Javanese, women to Buddhism.

In her lectures and writings, Parwati emphasises the significant role of both nuns and laywomen in the Indonesian Buddhayāna movement. She highlights the contributions of the female monastics in the Buddhayāna Sangha, pointing out that they have the same duties as monks in the running of temples, serving the spiritual needs of the lay congregation, and propagating the Buddha’s teachings in Indonesia. She also remarks that Buddhist nuns preached and initiated lay followers in various Buddhayāna organisations, serving both the lay male and female members of the movement. More importantly, Parwati points out that laywomen preachers such as herself were granted the authority to officiate wedding ceremonies and funeral rituals just like their male counterparts.

Over the years, as the chairwoman of WBI, Parwati gradually developed her ‘Buddhist feminist theology’ (teologi feminis Buddha) to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment within the Buddhist community in Indonesia. In her essay ‘Buddhist Feminist Theology in Indonesia’ (2002), she lauded the Indonesian government for their 1984 promulgation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Although she was glad that many new provisions had been proposed for the regulation, she believed that more could be done to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment in Indonesia.

Buddhist feminist theology became a key teaching in the Indonesian Buddhayāna movement

Concretely, Parwati believed that Buddhist feminist theology can help to achieve equality and liberation. Drawing on history, she pointed out that women were active Buddhist leaders in the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms of Srivijaya and Majapahit, and remained important leaders during the Dutch colonial and independence periods. Her linear historical narrative of Buddhist feminism serves to justify that Buddhism – and the participation of Buddhist women – had long been a part of Indonesian history.

In addition, Parwati tapped into Buddhist doctrines to claim that the Avalokiteśvara in Chinese Mahāyāna Buddhism and the Tara in Tibetan Tantrayāna Buddhism are a glorification of ‘feminine divinity’ in Buddhism. She suggests that the Mahāyāna concept of prajñāpāramitā, which refers to the ‘perfection of wisdom’, is personified as the ‘mother of all Buddhas’, which gives birth to the ‘noble teachings for humanity.’ Therefore, Parwati is critical of the Theravāda tradition, which opposes the ordination of women into the Sangha.

Parwati’s Buddhist feminist theology became a key teaching in the Indonesian Buddhayāna movement. In addition to serving as the chairwoman of WBI, she was also appointed as the rector of the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Ampel, the president of the Vimala Dharma Vihara Foundation in Bandung, and the vice president of the Indonesia Buddhayāna Council.

The case of Parwati helps us better understand women’s agency in promoting Buddhism and advocating gender equality in the world’s largest Muslim nation. More attention is needed to examine the much-neglected role of minority Buddhist women in the Muslim-majority countries of maritime Southeast Asia. These numerous Buddhist women’s stories remain to be told.