The British writer Norman Douglas was so famous during his lifetime (1868-1952) that he frequently turned up as a character in fiction. D H Lawrence, Aldous Huxley and Richard Aldington all put him in their novels, while Douglas’s own bestselling novel South Wind (1917) appeared on the shelves of characters in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945) and Vladimir Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941). Bombarded by fans who sought him out in Florence, his home base during the 1920s and ’30s, Douglas had his mail sent to the local Thomas Cook travel bureau to keep his address secret.

In May 1937, Douglas fled Florence, fearing that he was about to be arrested for raping a 10-year-old girl. He took a train to Monte Carlo, to seek refuge with his friend Oscar Levy, a wealthy German Jewish intellectual who had funded the first English translation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s collected works. Levy wasn’t bothered by the allegations against Douglas. He told him: ‘The Italians ought to have sent you yearly 12 boys and 12 girls as did the Athenians to the Minotaurus of Crete. On account of your literary merits. And because you are not a minotaurus, but a nice gentleman, who does the children good.’ Levy didn’t share Douglas’s sexual tastes, but he didn’t condemn them either. Douglas’s enthusiasm for young virgins of both sexes, in Levy’s view, was part of his appeal. Levy praised Douglas as the ‘last of the pagans!’

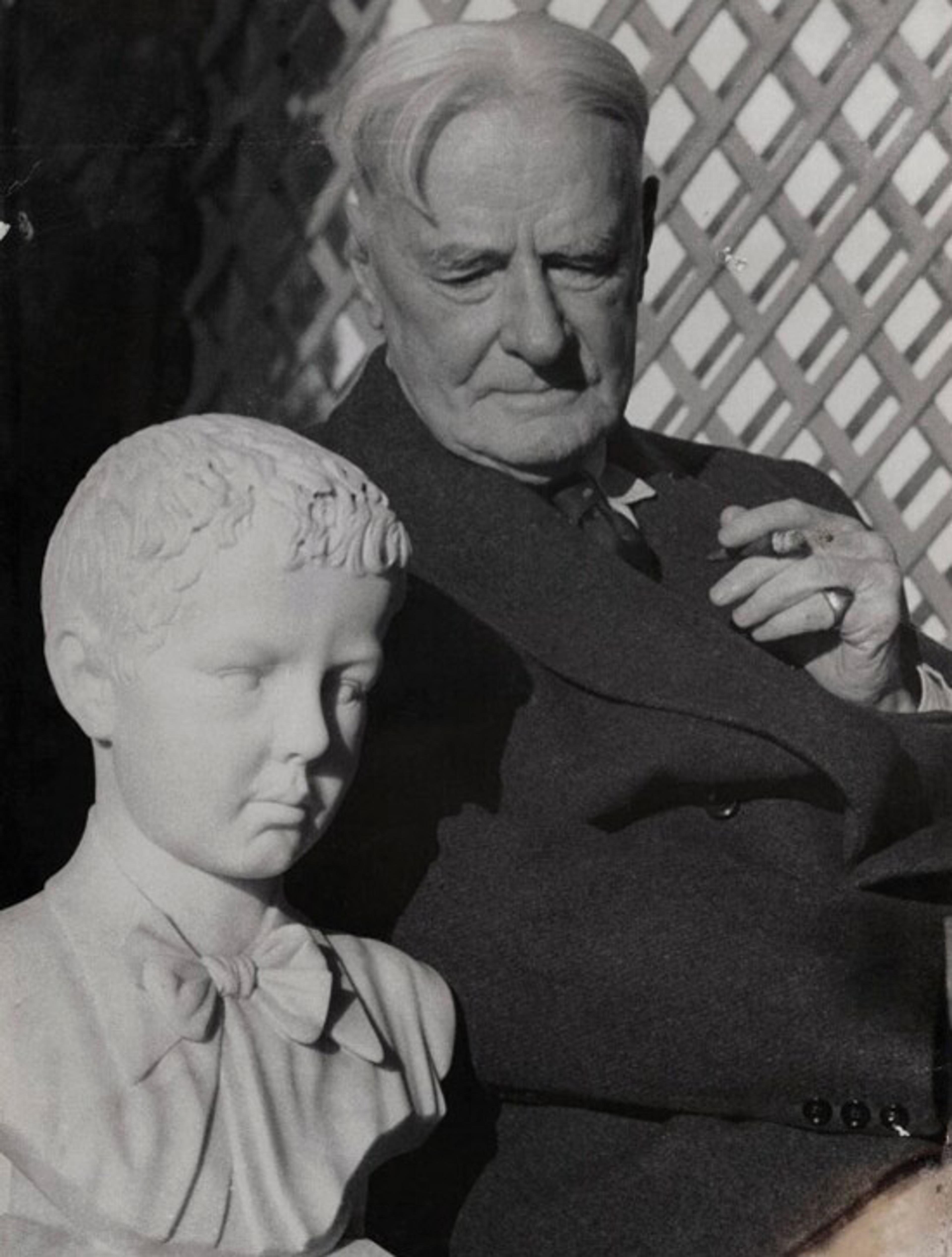

Norman Douglas with his own bust as a child, 1949. Unknown photographer. Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

It wasn’t just Nietzscheans who defended Douglas. Many within British literary circles blithely tolerated his pederasty, which he did little to hide. Renowned as a witty and ribald conversationalist, Douglas was given to bon mots such as ‘I’ve always loved a very large possession attached to a very small boy.’ The writer and actress Faith Compton Mackenzie said that ‘the tang of his salty conversation delighted me’. When Douglas was charged in November 1916 with indecent assault on two male cousins, ages 10 and 12, she volunteered an alibi in court. She included this anecdote in the first volume of her memoirs, saying that she considered her testimony to be her ‘war work’. Mackenzie’s alibi helped to get Douglas released on bail, enabling him to flee Britain and resettle in Italy.

Douglas’s 1916 arrest was widely reported in the British press. His notoriety helped make South Wind a bestseller. Twenty years later, Douglas’s flight from Italy in 1937 was also reported in the British papers, which again didn’t fatally damage his popularity. When Douglas was forced by the Second World War to return to London in 1942, he was welcomed by a new circle of literary friends, including Viva King, Constantine FitzGibbon and Brian Howard. After the war, Douglas returned to Italy, where he was befriended by Graham Greene, one of the era’s most popular writers. And after his death, in 1952, when critics attacked him for abusing children, Greene staunchly defended Douglas’s posthumous reputation.

Today it’s impossible to imagine how such a notorious paedophile could be admired by so many people despite his sexual behaviour. What explains this change? And does this historical episode help us understand anything about present-day willingness to turn a blind eye to blatant sexual abusers, such as the American financier Jeffrey Epstein and the French writer Gabriel Matzneff?

It might feel natural to presume that the moral injunction against sex between adults and children is timeless. But today’s extreme antipathy to paedophilia dates only to the 1980s, when contests over masculinity and homosexuality inspired an outburst of panic about child abuse. ‘Not until the 1980s did the signifier of paedophilia accrue the kind of abhorrence and horror that it connotes today,’ argued the historian Steven Angelides in 2005. Before the 1980s, attitudes towards sexual encounters between adults and children or youths – boys and girls – were far more ambiguous.

The gulf in power between adults and children didn’t trouble past sexual norms, which defined appropriate sex as that which took place between husband and wife, unequals whose different roles the Bible prescribed. European law before the past 200 years codified no ages of sexual consent except in England, Wales and Saxony, where the age of consent for girls was set between 10 and 12 years old. If sex between men and girls took place in marriage, it was sanctioned; if it took place outside of marriage, it was unsanctioned. Boys had no age of consent. They were regarded as potential perpetrators but seldom as victims. If they were physically capable of engaging in sexual relations, the law held them criminally responsible for their actions, and hence subject to punishment for their role in same-sex pederastic encounters with adult men.

‘Homosexuality’ emerged to differentiate male same-sex relations involving adults from this pederastic legacy

States enacted new legal ages of consent, first for girls and later for boys, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, but a significant gap remained between prescription and practice. In much of the Western world, courts remained concerned only with the potential victimisation of girls, and saw boys who had sex with men as predatory potential blackmailers. Concern for girls depended on their status relative to the man who abused them, and focused on their marriageability. The age of consent for marriage remained low throughout the 20th century, and marriage itself eliminated any restrictions on the sexual age of consent. In Britain, for example, before 1929, even if they couldn’t consent to sex outside marriage until age 16, girls could consent to marriage (and sex within marriage) at age 12.

Social and legal concern about boys and sex during this time had less to do with age than gender. Moral and legal authorities didn’t worry about the welfare of boys who had sex with girls or women. They were concerned only about the immorality of boys who had sex with adult men. Before the early 20th century, age-differentiated sex was the paradigmatic form of male same-sex practice in the West. In English, French and Italian, the language reflected that understanding, as the terms ‘pederast’, pédéraste and pederasta described men who had sex with other males. Often, these sexual encounters took the form of prostitution, in which boys and youths sold sex to older men. The historians Jana Funke and Kate Fisher have recently shown that the concept of ‘homosexuality’ emerged as a means to differentiate male same-sex relations involving adults from this pederastic legacy, and thereby to give affective adult same-sex behaviour more legitimacy.

Pederasty had its defenders. In the mid-19th century, a neo-Hellenist intellectual movement swept German and British universities. Scholars such as Karl Otfried Müller, Walter Pater and John Addington Symonds embraced ancient Greek history and philosophy as models for modern liberal politics and society. These neo-Hellenists placed pederasty at the centre of the Greek model, defining the pederastic relation as one ‘by which an older man, moved to love by the visible beauty of a younger man, and desirous of winning immortality through that love, undertakes the younger man’s education in virtue and wisdom.’ In this lofty vision, pederasty didn’t entail a sexual relationship, but took place on a higher spiritual plane. In point of fact, both Pater and Symonds were sexually attracted to male youths. Their writings influenced Douglas and other pederasts who came of age in the late 19th century. When concerns about the sexual trafficking of girls began to heat up in the 1880s, catalysing the passage of new age-of-consent laws, Symonds rejected age-differentiated pederasty. He became a homosexual-rights advocate, defending age-consistent reciprocal relations between adult men. Many early activists joined Symonds on this path. Others, like Douglas, remained enamoured of pederasty.

Pederasty served as a positive framework that men used to defend their sexual relations with boys and youths during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Douglas presented his own sexual encounters in this light. (Most of his encounters were with boys; his encounters with girls were the exception to the rule.) His writings often celebrated the Hellenic past. Douglas’s travel books about Italy delved into the history of the country’s ancient Greek colonies. In Old Calabria (1915), one of his most beloved books, he wrote about the Achaean colony of Magna Graecia that had preceded modern Calabria. In the book he noted: ‘Calabria is not a land to traverse alone.’

As that suggests, Douglas didn’t make the trip by himself but with a companion, a cockney boy named Eric Wolton whom he’d first picked up at a Guy Fawkes celebration in Crystal Palace, when Wolton was 12. On their travels together in Italy, Douglas tutored Wolton in reading and writing. Wolton kept diaries, practised writing correspondence, and worked on spelling words assigned by Douglas, all in keeping with the pederastic model. Following the ancient Greeks, Douglas also had sexual encounters with Wolton. He took a naked picture of him on the beach in Calabria, which he likely showed to select friends. Many of Douglas’s London friends met Wolton, since the boy was often in his company during the early part of that decade.

Many of the children who had sexual encounters with Douglas later expressed nostalgia for their times together

The framework of pederasty enabled all parties – Wolton and his parents, Douglas, and Douglas’s friends – to accept the relationship between the man and the boy. It enabled men like Levy to say that Douglas did the children good, a common sentiment. The writer Reggie Turner, a member of Oscar Wilde’s circle who’d moved to Florence after Wilde’s arrest, thought that Douglas was so good with children he should have been a schoolmaster. Harold Acton, the Florence aesthete, went even further than Turner, remarking wistfully that ‘such a schoolmaster would have been ideal, and I regret that I met him too late, when I was more or less crystallised.’ Acton, who witnessed many of Douglas’s intergenerational affairs in Florence, including the final episode that led to his flight from the city, was under no illusion about the nature of Douglas’s relationships with children. He simply didn’t condemn Douglas for his sexual behaviour. Rather, he romanticised it. Likewise, Douglas’s close friend Giuseppe ‘Pino’ Orioli, a rare-bookseller and publisher, who remarked in his diary in 1934 that it was a pity he hadn’t met Douglas when he was a child: ‘I am sure he would have handled me beautifully.’ Orioli frequently recorded the details of Douglas’s sexual encounters with children in his diaries, so there can be no question what he meant by the word ‘handled’.

Most shocking to today’s mores, perhaps, is that many of the children who had sexual encounters with Douglas later expressed nostalgia for their times together, and appreciation for Douglas’s role as an educator and mentor. After serving in the First World War, Wolton took a job as assistant inspector of police in what was then the British colony of Tanganyika (now Tanzania). In the autumn of 1921, he caught typhoid and was hospitalised in Dar es Salaam. During his convalescence, Wolton wrote letters to Douglas. ‘Doug, I have wanted Italy and you as bad as anything last week,’ he said. ‘They were happy times too Doug wer’nt [sic] they, I have no evil thoughts about them.’

In fact, his appreciation for Douglas only intensified the older that he got. ‘You are more to me than ever you were,’ he wrote in another letter, ‘the difference is now that I am old enough to realise it.’ Decades later he told a friend that, if it hadn’t been for Douglas, ‘I would have been doomed for all times.’ When he’d met Douglas at Crystal Palace, Wolton had been a delinquent, as he put it. He said that Douglas had taken him away from a life of dishonesty and violence, educated and mentored him, and set him on the path to professional and personal success. In the early 1950s, Wolton brought his children to see Douglas in Italy before the old man died. His loyalty and affection for the writer were fairly typical of Douglas’s past connections.

Many of Douglas’s boys remained on friendly terms with him throughout their adult lives, inviting the writer into their homes and introducing him to their wives and children. He was not the only pederast to find warmth and welcome among his former boys. Social scientists have found that many men hold positive feelings about ‘willing’ childhood sexual experiences they had with adults. Some explain these positive memories as expressions of child sexual abuse accommodation syndrome (CSAAS), akin to Stockholm syndrome, while other social scientists have challenged CSAAS as junk science. From a historical perspective, the underlying psychological structures that might or might not explain children’s positive attitudes to sexual encounters with adults are less significant than the observation that, during the 20th century, such attitudes were surprisingly common.

Sex between men and girls could be made licit through marriage. But sex between men and boys was always stigmatised during the 19th and 20th centuries. Social and legal proscriptions on pederastic sex varied by time and place, with some regimes far more punitive than others. Italy, for example, decriminalised sex between males in the 19th century, and many communities tacitly accepted sex between boys, or between boys and men, as a release valve that would shore up the sexual restrictions on girls and women. But Italian civic and religious authorities looked on such sex between boys and men more as a necessary evil than as a positive good. A broad moral consensus remained staunchly antagonistic to pederasty.

Popular toleration of pederasty, in Italy and elsewhere, took the form of wilful ignorance. As the American literary theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick pointed out in Epistemology of the Closet (1990), ignorance is not a singular ‘maw of darkness’ but a multiple phenomenon. Ignorance can entail intentional not-knowing, making the closet a performance of silence as a speech act. The Australian anthropologist Michael Taussig called communal expressions of wilful ignorance ‘public secrets’ that rested on ‘active not-knowing’. The experiences of the German photographer Wilhelm von Gloeden demonstrates how such a public secret, or active not-knowing, operated. Gloeden lived in Taormina, in Sicily, from 1878 to his death in 1931. During his decades of residence, he photographed generations of boys, frequently posing them naked in Hellenic ruins, adorned with laurel crowns and other symbols of ancient Greece. Gloeden’s photographs were popular with many early gay activists, including Symonds. The people of Taormina, who benefitted from the tourist trade that Gloeden’s photography brought to their town, also liked him. Gloeden and other foreign men often paid local youths for sexual encounters, an open secret in the community. Locals silenced any journalists, priests and politicians who attempted to criticise Gloeden, since they felt that these criticisms dishonoured the community and threatened their economic wellbeing. As Mario Bolognari, a historian of Taormina, concluded in 2017: ‘having chosen not to see does not imply being blind. It only means having decided that it was preferable not to notice certain things.’

They maintained a deliberate ignorance about what happened between Douglas and the boys and girls

Active not-knowing happens at the intimate level as well as the communal level. Families engage in active not-knowing about sexual wrongdoing in the home. This applies not only to child sexual abuse, but to all sorts of misbehaviours, including adultery, sibling incest and domestic violence. The motivations for active not-knowing are various, ranging from love and loyalty for the offender, to fear of retribution, to a desire to shield the family from public shame. Active not-knowing applies to more than sexual misbehaviour, and extends beyond the family. Friends exercise active not-knowing on behalf of friends, not wanting to risk meaningful relationships. Fans of artists engage in active not-knowing about their idols, motivated by awe and admiration, or by a desire to protect a favourite artwork from scrutiny and rejection. And disempowered people engage in active not-knowing about the powerful, from fear of the consequences that might result from confronting the truth, or from appreciation for the benefits that accrue from maintaining ignorance. Lastly, everyone benefits from silence by avoiding being implicated themselves in the bad thing that they know about.

Many of these ways of not-knowing helped Douglas escape condemnation. Some members of his extended family disowned him because of the abusive way he treated his wife, who was his first cousin and thus their relation as well. But his sons, who witnessed firsthand his sexual encounters with children (and might even, in the case of his older son, have experienced abuse) maintained loyalty to their father and defended him from posthumous accusations. Some writer friends wrote off Douglas after his arrests, but many loved his books and maintained a deliberate ignorance about what actually happened between Douglas and the boys and girls he recounted meeting in the pages of his travel books. The children themselves knew the most about Douglas’s sexual predations, but they had the most to gain financially – and often emotionally – from keeping close to him. There’s almost no evidence of children speaking out against Douglas either during their connections or afterwards, as adults. One exception is a 16-year-old whose complaint led to Douglas’s initial arrest in London in 1916.

The lack of panic about paedophilia during Douglas’s lifetime made it easier for all these people to look the other way, even when he flaunted his predilections. Douglas went so far as to write about how he’d purchased children for sex in his memoir, Looking Back (1933). Very few reviewers took issue with the material, at least until after Douglas’s death, when, freed from the fear of a libel suit, they pointed out how unseemly it was for Douglas to have admitted to such behaviour. The author and former politician Harold Nicolson complained that he was ‘shocked by people who, when past the age of 70, openly avow indulgences which they ought to conceal’. In the eyes of reviewers who wanted to maintain the pretence of active not-knowing, Douglas’s admission might have been a worse crime than the acts themselves, since they implicated the readers by forcing them into a state of knowing.

If Douglas escaped condemnation during his lifetime, he couldn’t escape the assault on his reputation following the intensification of anti-paedophilic sentiment after his death. The shift in public mores during the 1980s towards viewing paedophiles as monsters made it impossible to defend Douglas. He disappeared from literary memory, except as an example of historical villainy – the role he plays in two novels published after the 1980s, Francis King’s The Ant Colony (1991) and Alex Preston’s In Love and War (2014). Most readers would consider that a salutary change and welcome the expulsion of paedophiles from acceptable society. However, the rise of the ‘monster’ discourse doesn’t seem to have made people much more willing to speak out against child sexual abuse in the present.

Looking at the example of Epstein, one can see the same old dynamics of active not-knowing operating among the leadership of the MIT Media Lab (who accepted donations from Epstein) and the scholars who turned a blind eye to his abuse, even after his conviction. The Media Lab didn’t want to lose Epstein’s financial patronage or be shamed by association. Individual scholars might have enjoyed his company (and the company of the girls and young women Epstein surrounded himself with), or they might have wanted funding from him, or feared the consequences to their careers if they spoke out against him. In an even more striking parallel to Douglas, Matzneff wrote and spoke openly about his paedophilia without censure, protected by fellow writers’ and publishers’ unwillingness to disturb the dense network of literary connections in which they all played a role, until one of his victims of abuse, the French publisher Vanessa Springora, broke the silence in 2019.

Is it possible that elevating the paedophile to the status of a monster has in fact, rather than making it easier to speak out against child abuse, made it more imperative for friends, family members and fans to engage in active not-knowing? Who wants to expose someone they love as a monster? More than that, people are inclined to disbelieve tales of extraordinary monstrosity. Who wants to disturb their own situation by making such explosive allegations? The stakes are too high to risk getting it wrong. Maybe it would be easier to counter the problem of child sexual abuse if we were able to acknowledge it as both bad and ordinary. In Douglas’s day, such sex was seen as questionable but mundane. Today, it’s seen as terrible but exceptional. If we could create a world where people agreed that sex between adults and children was not healthy for children, and that many ordinary adults engaged in such behaviour nonetheless, maybe more people would feel empowered to witness and speak out against everyday abuse.

Unspeakable: A Life Beyond Sexual Morality (2020) by Rachel Hope Cleves is published via The University of Chicago Press.