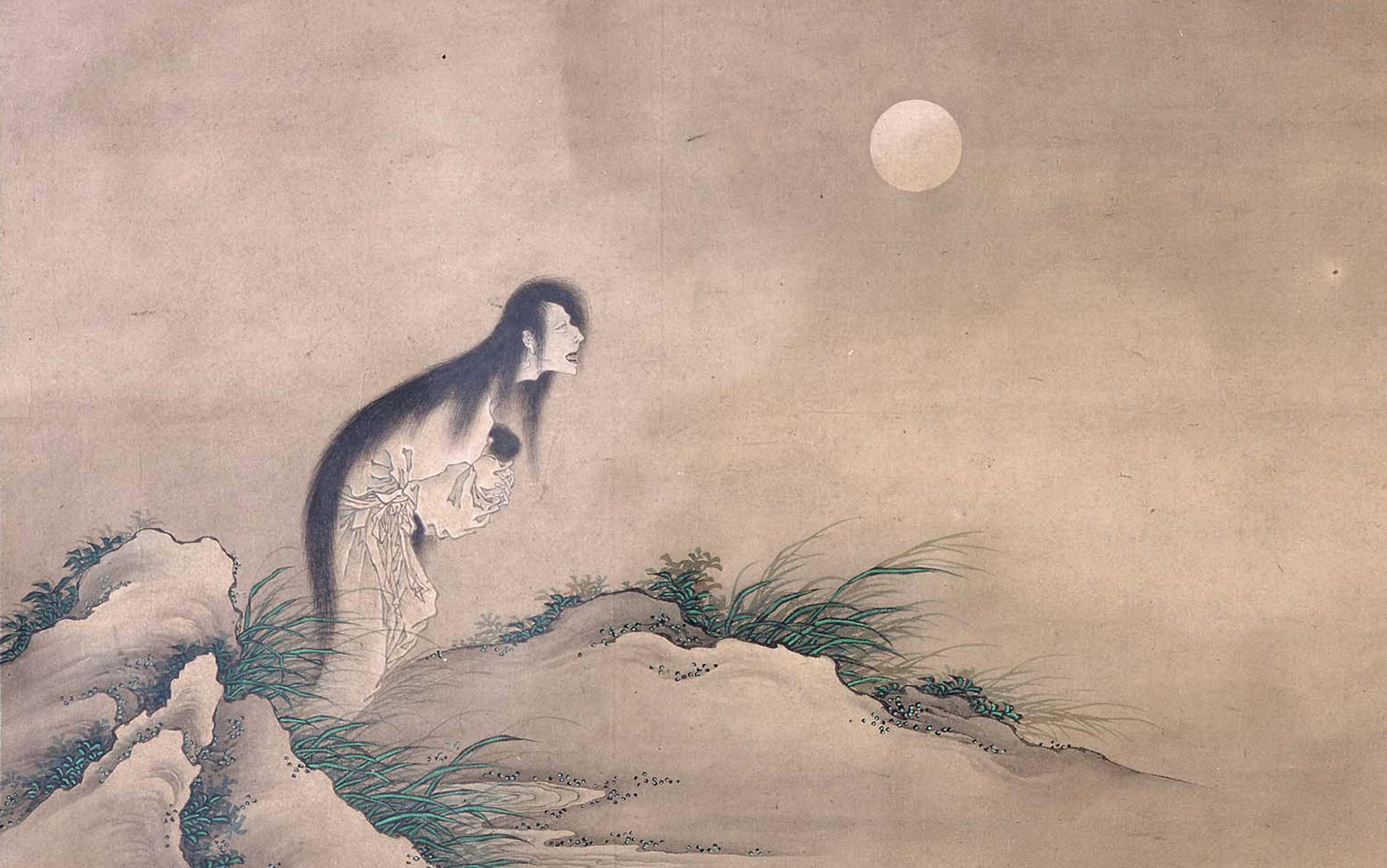

On the 11th floor of a suburban Hong Kong tower, an 86-year-old woman lived alone in a tiny, decrepit apartment. Her family rarely visited. Her daughter had married a man in Macau and now lived there with him and their two children. Her son had passed away years earlier, and his only child now attended a university in England.

One September evening, the old woman fell and broke her hip while trying to change a lightbulb. She couldn’t move, and no one heard her crying for help. Over the next two days, she slowly died from dehydration. It took an additional three days for the neighbours to call the authorities – three days for the stench to become truly unbearable. The police removed the body and notified the family. A small funeral was held.

A few weeks later, the landlord had the apartment thoroughly cleaned and tried to rent it out again. Since the old woman’s death was not classed as a murder or suicide, the apartment was not placed on any of Hong Kong’s online lists of haunted dwellings. To attract a new tenant, the landlord reduced the rent slightly, and the discount was enough to attract a university student named Daili, who had just arrived from mainland China.

On the first night that Daili slept in the apartment, she saw the blurry face of an old woman in a dream. She thought little of it and busied herself the next morning by buying some plants to put on the apartment’s covered balcony. She hung a pot of begonias from a hook drilled into the bottom of the balcony above.

The next night, Daili saw the woman again. And so it went every night, with the old woman’s face becoming more detailed in each new dream. Sometimes the woman would speak to her, asking her to visit:

Why don’t you come by? Where are you? How long until you come again?

As the dreams persisted, Daili had trouble sleeping. Sometimes, rather than lying awake, she would go to the balcony to water her plants or look at the Moon.

One night, the dreams were particularly vivid, but even after Daili woke up and went to the balcony, the woman’s voice didn’t stop.

Come visit me. Where are you?

Daili climbed a small step ladder to water her begonias at the edge of the balcony.

I’m lonely. You never stop by.

Daili poured some water into the flowerpot.

I need your help, now!

‘OK,’ Daili replied.

She looked out over the edge of the balcony, jumped from the stepladder, and fell 11 floors to her death.

The police ruled the death a suicide, and the apartment was listed on the city’s online registers for haunted apartments. The landlord had no choice but to discount the rent by 30 per cent – and wait for a tenant who did not believe in ghosts.

When a university student in Hong Kong first sent me this story, which I have translated from Chinese and slightly modified, I knew it wasn’t true. Many similar fictional tales of ghosts, hauntings and unnatural deaths can be found online. Though these stories are not factual reports, I have found they reflect the experiences and anxieties of many who live in urban China: elderly parents left without family at the end of their lives; ghosts harming strangers (even leading them to take their own life); a pervasive fear of death; and a strengthening relationship between a fear of ghosts and the real estate market.

This may appear counterintuitive. In the official view, a belief in ghosts is mere superstition, a vestige of a traditional agricultural society that has been left behind in the name of progress. There is an assumption that people in cities should be less superstitious than their rural neighbours. But ghostly beliefs are integral to the experience of urban living and rapid urbanisation. Though a fear of ghosts may have a long history in China, I suspect that such beliefs both transform and deepen during the process of urbanisation. And, in turn, these fears are altering social life and urban space as they become tangled up with the remembrance and repression of the dead.

The deceased’s body is typically kept at home in a coffin for a few days between the death and the funeral

Belief in ghosts takes an ambiguous form in contemporary urban China. Though not everyone admits to believing in them, almost everyone I spent time with during decades of ethnographic research in Nanjing, Shanghai, Jinan and Hong Kong has acted in ways that implied that ghosts exist. These people took special precautions when visiting cemeteries and funeral homes; they indicated that abandoned buildings felt haunted; they avoided talking about or having any association with death, including not renting or purchasing apartments that might be, in their words, ‘haunted’.

I have been conducting anthropological research in China since the late 1980s. Back then, I lived in a rural area of Shandong province, at a time when few non-Chinese had the opportunity to live in a Chinese village. I came to Shandong province to investigate patterns of social interactions among village families, and it was here that I was first exposed to rural funeral practices, which are relatively similar across China. After someone dies, the deceased’s body is typically kept at home in a coffin – sometimes made from cedar, now often refrigerated – for a few days between the death and the funeral. People come by and pay their respects to the body, give a gift, and offer condolences to the family. The funeral itself is organised and conducted by familial elders. After the funeral, the body is either buried intact on village land or first cremated and then buried. But in all my time in rural China, I never heard anyone complain that their neighbour might be keeping a dead body at home. I never heard anyone say that the fields where they worked – and where their relatives were buried – were ‘haunted’.

I assumed funerals and beliefs about the dead would be similar in the cities. But I didn’t really know much about urban funerary practices. In the years after living in Shandong province, I had attended only a few urban memorial services for friends and relatives (my wife is from the city of Nanjing). All of that changed when I began a research project on funerals in Chinese cities.

In 2013, I began interviewing people who worked in China’s urban funerary sector and visited funeral homes and cemeteries in many Chinese cities, with a particular focus on Nanjing and Hong Kong. I found that funerary practice in urban China differed considerably from that in rural locales. In general, people in rural areas appeared less afraid of death, dead bodies and places of burial than people living in cities.

As soon as a dead body is discovered in Nanjing, Shanghai and Hong Kong, it is removed from the home or hospital room and taken either to a hospital morgue or a funeral home. The funeral is organised and conducted by industry professionals rather than family members. After the funeral, the body is cremated and the ashes are buried in a cemetery or a columbarium located far from the city centre – in Shanghai, it took me more than two hours by public transport to reach the popular cemetery, Fu Shou Yuan.

When I described rural funeral practices to people in large Chinese cities – where everyone lives in apartment buildings – most found such practices distasteful. One man I interviewed in Nanjing was particularly disgusted by the idea of keeping a body in an apartment, even if it was kept in a refrigerated casket with no smell. Such a practice, he said, would bring bad luck and disrepute to the people who lived in the same building. And besides, he added, it would be illegal to keep a dead body in an apartment building. Indeed, when I asked government officials in Nanjing and Hong Kong about such a law, they confirmed that anyone who discovered a dead body in a home setting was required to notify the local government immediately and that the government would organise the removal of the body as soon as possible.

In China’s largest cities, even practices that announce death publicly have been outlawed. Some of my students at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who came from small cities in central China told me about funerals in their hometowns where tents for attendees were set up outside apartment blocks. But such tents are no longer permitted in large cities such as Shanghai or Tianjin.

Mourners stepped over the fire to counter the yin energy that comes from spending time around the dead

In Nanjing, I have seen home altars in family apartments with pictures of the deceased as a replacement for keeping a body at home. Friends and relatives could visit these home altars and pay their respects. But because of the steady stream of guests coming and going, and the visible placement of symbols related to death on the apartment’s front door, other residents would often become aware that someone in the building had passed away. In Nanjing, though some people set up home altars, others said they found the practice distasteful. As one woman told me during an interview: ‘How dare a family be rude enough to announce that something as inauspicious as a death had happened in their apartment building!’

In the largest cities I visited, including Shanghai and Beijing, I was repeatedly told that no one set up home altars. In Tianjin, a city of about 15 million, I saw an official billboard explaining that it was now illegal to set up a home altar in an apartment. If neighbours notified the government that a resident had set one up, a large fine would be imposed.

It seems that the larger the city, the more likely it is that neighbours will not want to know about a death in their apartment block, and the more likely it is that practices announcing death will become illegal.

While interviewing funerary professionals in the 2010s, I learned that urban distaste for announcing death was matched by a cautious attitude towards visiting places associated with death. Urban funerary professionals often told families how to counter the ghostly energy, considered ‘yin’ in the yin/yang dichotomy, that permeates places like funeral homes and cemeteries. This yin energy can be countered with yang activities, including drinking warm, sugary liquids, going to places that brim with people, or performing a fire-stepping ritual. In Shanghai and other cities, places for stepping over fire are built into the exits of funeral homes.

After observing a funeral in Nanjing, I watched a funeral professional light a small grass fire on a metal platform they had set up in the parking lot. The mourners all stepped over the fire before leaving to absorb yang energy and counter the yin that comes from spending time around the dead. I never saw such a ritual at a rural funeral.

People in China’s major cities, it seems, fear dead bodies and burial places more than people in rural areas. Even the thought of a death occurring in their neighbour’s apartment bothers them. Rapid urbanisation seems to intensify a fear of death. And this fear eventually leads to the removal of death-related infrastructure from urban areas. Throughout China, cemeteries and funeral homes are constantly relocated away from city centres. The rapid expansion of cities and their borders has necessitated the repeated relocation of state-run funeral homes and crematoria, requiring many cemeteries to be dug up. When I asked one Nanjing official why, he said:

People are still afraid of ghosts. The value of real estate near cemeteries and funeral homes is always lower than in the central districts. So, to protect the value of its real estate, the municipal government always attempts to keep funeral homes located far from the city centre.

I once told an official in Nanjing’s Office of Funerary Regulation about an American relative of mine whose ashes were scattered in his favourite park. The official replied:

[W]e cannot allow people to dispose of their parent’s ashes in public parks. People fear ghosts. People would not like Nanjing’s parks if they thought they had ghosts, so it is illegal to scatter cremated remains there, even if they do not pollute the environment and are indistinguishable from the rest of the dirt.

If a neighbour fears death or dead bodies, then they have the right to restrict the activities of an undertaker

In Hong Kong, fears of the dead echo those on the mainland. This fear even impacts the operation of funeral parlours (places where funerary rituals may be conducted). As of 2022, Hong Kong has only seven licensed funeral parlours and approximately 120 licensed undertakers, who help with funerary arrangements but do not have the facilities to conduct funerals. Only those undertakers who started their businesses before the current regulatory regime began in the 2000s can openly advertise the nature of their business, display coffins in their shops and store crematory remains. These businesses have what are called type-A undertaking licences. Those with type-B licences cannot store cremated remains or display coffins in their stores if any other business or homeowners in their vicinity object. Those with type-C licences are even further restricted: they may not use the word ‘funerary’ in the signs displayed publicly in front of their stores.

The logic here is the same as described by people I spoke with in Nanjing: if a neighbour fears death or dead bodies, or fears that other people’s fear could affect the value of their business or property, then they have the right to restrict the activities of an undertaker. In practice, this means that the business activities of all proprietors with type-B and type-C licences are affected.

Currently, most of the undertakers with type-A licences are in the Hong Hom residential district of Hong Kong, and many apartments there have a window from which one can see an undertaker’s shop (and shop sign). These apartments rent for less than those without such a view. In Hong Kong, as the story of Daili’s suicide reminds us, there are online resources one can use to locate ‘haunted dwellings’ where unusual deaths have occurred. These apartments also sell and rent for discounted prices.

So why are modern Chinese urbanites so afraid of ghosts? Four factors seem important: the separation of life from death in cities, the rise of a ‘stranger’ society and economy, the simultaneous idealisation and shrinking of families, and an increasing number of abandoned or derelict buildings. What is important to note here is that all four factors are products of urbanisation itself. Urbanisation makes ghosts. There is also a fifth point, which is distinct from these other factors but still compounds the haunting of modern China: a politics of repression.

The first factor is the increasing separation of life from death. People in cities don’t usually die at home. Instead, they die in hospitals, where staff do all they can to hide dead bodies. Even in cases when someone doesn’t die at a hospital, dead bodies are quickly taken to be stored at funeral parlours. The result is that many people in China’s major cities have never seen a dead body. This separation only increases as cemeteries and funeral homes are moved further and further away from city centres. The less people experience death, the more fearsome it becomes. For many, just mentioning death is inauspicious.

More important, I believe, is the second factor: the rise of a ‘stranger’ society and economy. In village settings, relatives are buried together in the same vicinity, but in urban cemeteries strangers are buried side by side – a situation comparable to large apartment buildings where neighbours may not know one another. In urban China at least, the concept of ghost (鬼, Romanised as ‘gui’, refers to malevolent spirits of many types, but also, perhaps metaphorically, to malevolent people or even animals) is directly related to the notion of the ‘stranger’. Kin become ancestors; strangers become ghosts. Ghosts can do evil and must be feared. In the opening story, the ghost of the old lady leads Daili to suicide. In burial ceremonies at urban cemeteries in Nanjing, funeral practitioners often introduce the newly buried to their ‘neighbours’ in the hopes that the spirits next door will not act like ghosts.

Urban economies are economies of strangers. In cities, we purchase goods and services from those we do not know and hope these strangers treat us fairly. Most crucially, funerals in Chinese cities are arranged and run by strangers. These strangers handle the bodies at the funeral homes and crematoria, and they work in hospital morgues and cemeteries (or at stalls outside, selling flowers and funerary paraphernalia).

As in many places around the world, workers in this sector are stigmatised. They have trouble finding marital partners and often marry each other. They avoid shaking hands with their customers. They lie about their occupation to strangers and tell their children to do the same if anyone asks about their parents’ line of work.

This stigmatisation of funerary sector workers is related to the fear of ghosts in cemeteries. A comparison with how sex work is viewed in China is illustrative: a woman who has sex with her husband is seen as an upstanding citizen, but a woman who has sex with strangers for money is seen as a polluted, polluting figure. Likewise, a person who helps with the funeral of a relative in a village is a moral person, but those in cities who help with the funerals of strangers for money are to be shunned. Burying ancestors is an act of filial duty; burying strangers and dealing with their ghostly yin energy exposes one to spiritual pollution. Because they are stigmatised, both sex work and funerary work can be relatively lucrative forms of employment. Both sectors cross uncomfortable lines between domains of the familial and the monetised economies of strangers.

We must learn to live with our ghosts rather than repress them

Related to this idea is the third factor behind the fear of ghosts in urban China: the idealisation of family. As China urbanises and modernises, not only does contact with strangers become more prevalent, but the size of families and households also shrinks. Rather than a person’s entire social world being composed of relatives of varying degrees of distance, the social universe of urbanites is composed of a few close relatives and a larger society of strangers and acquaintances. As families shrink, the contrast between kin and non-kin becomes more critical. Family becomes an idealised site of moral interaction; the world of strangers is where one might face exploitation, robbery and treachery. But if a family shrinks too much, a person might become completely isolated, and end up a ghost – like the old woman in the story.

As China urbanises, its ideas about ghosts are transforming. Only in urban and urbanising China are ghosts equated with strangers. In traditional, rural Chinese society, ghosts were often thought of as relatives or kin who had been mistreated in life and not given a proper burial. The whole purpose of a funeral was to make sure that a dead relative became an ancestor instead of a ghost. When a person’s social universe is composed almost entirely of family, then both good and evil must be located within the family. In urban settings, these can be separated: family can be imagined as purely good, while evil is located in strangers.

A century ago in rural China, dead infants, toddlers and young children were not given any funerals at all. Their bodies were tossed into ditches for animals to consume. They were thought of as evil spirits, ghosts of a sort, that had invaded a woman’s womb and would return again if given a proper burial. But in contemporary urban China, losing a child is one of the most painful things imaginable. Dead children can receive elaborate funerals and children’s tombs are often the most ornate of all. Dead children represent only the love of their families and are never associated with evil. Family is sacred; strangers (and their ghosts) are dangerous.

The fourth factor related to the haunting of Chinese cities is the existence of abandoned buildings, neighbourhoods and factories. These places once brimmed with life, but because they are slated for urban renewal, residents and workers have been forced out. Empty and often derelict, they remind the people who are left behind (or who live nearby) of the loss of communities or ways of life. Areas targeted for renewal include rural areas but also previously urbanised locations, especially those not so intensely built up. After redevelopment, these areas become new districts that rise higher and are more densely populated. The communities affected by these projects may have protested, or attempted to protest, but in China such protests are often quickly suppressed.

Ghosts are not only strangers, but also someone or something that should not be remembered, at least in the eyes of an authority figure. Since memories of them are repressed, these spirits must actively haunt the living to receive recognition. The political repression of these memories, especially prevalent in China, makes them only more spectral. This leads to the final point: the ways that a fear of ghosts is connected to a broader politics of memory and fear. Projects of urban renewal are simply one of many occasions that could potentially lead to anti-government protests, and, in the eyes of the government, all such resistance must be suppressed. The current Communist Party regime in China imagines its spirit must live forever; all other spirits are ghostly enemies, strangers, to be banished. From this perspective, the ghosts from the party’s now-repudiated past – the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution or the Tiananmen Square massacre – must never be mentioned again. But I believe that the totalitarian impulse of the Communist Party regime to banish all spirits other than that of the party itself can only increase the haunting of urban China. We must learn to live with our ghosts rather than repress them.

In urban China, a fear of ghosts is not a rapidly disappearing vestige of a traditional rural past. It is produced in the process of urbanisation itself and politically amplified. The separation of life from death, the rise of stranger sociality, the idealisation of family and its separation from the wider society, the constant disruption of communities of living and production, and the repression of their memory all contribute to the haunting of urban China. It is a haunting narrated through ghost stories of all kinds, which tell of spirits arising from familial abandonment, the destruction of urban areas in the process of urban renewal, and wrongful deaths caused by strangers, like that of Daili and the old woman. These narratives tell us both that the demise of extended families and communities increases the chances that we will die alone, and that, as we depend more and more upon strangers in all aspects of our lives, we become more vulnerable to harm.

In China’s cities, cemeteries and funeral homes are visited only when necessary and dead bodies are rarely, if ever, seen. Yet death still forces its way into our personal space. Its sudden and unwelcome appearance makes it only more spectral. As our urban lives increasingly involve interactions with strangers, with people or beings whose comings and goings are complete mysteries, more and more ghosts haunt our cities. As urban neighbourhoods are razed and rebuilt again and again, as urban economies are restructured and disrupted over and over, as the pace of societal change increases and political repression continues, the memories that haunt us will only multiply.