Mata Hari, the Dutch exotic dancer and convicted spy, once told a journalist why she left Holland for Paris in 1902: ‘I thought all women who ran away from their husbands went to Paris.’ In another version of this transformative moment, she arrived at the Gare du Nord, with half a franc in her pocket, and went straight to the Grand Hotel on fashionable rue Scribe.

Neither recollection of these events was true, strictly speaking; yet in interviews, Margaretha Geertruida Zelle MacLeod would glide seamlessly from the harsh and mundane reality of her abusive marriage straight to performing at the best venues across Europe. While Mata Hari’s story has always attracted media attention for the light it sheds on the intelligence services during the First World War, its enduring appeal lies in its significance for feminist historians.

Gretha (as she was known before her fame) could have easily followed the trajectory of the fallen angel, so beloved of Victorian writers, slipping from bourgeois respectability into prostitution and an ignominious early death. But as an expert at self-fashioning, she transformed herself into an ‘Oriental’ exotic – taking the stage name Mata Hari: eye of the day, the dawn in Malay – whose fluid moves and revealing costumes were considered by contemporary critics to be the height of modernist expression. Mata Hari defied expectations, and yet the angel did fall from that brief moment of grace when she trespassed into the male sphere of espionage, unaware that this was more than just another performance.

The story of Mata Hari, the double-agent executed by the French military on espionage charges in a suburb of Paris on a damp October morning in 1917, belongs to the history of the intelligence services; but it is also a story of female defiance. The metamorphosis of the hat-maker’s daughter from Leeuwarden in the Dutch province of Friesland into a ‘star of dance’, then ‘the greatest spy of the century’, reveals much about the social roles (and limitations) placed upon even bourgeois women in the fin de siècle. Women such as Gretha needed to be tactical to gain financial independence from their husbands and fashion their own identities, to hide shameful or abusive pasts. In Mata Hari’s case, her self-invention as a stage performer coincided with the cross-currents of modernist art, the burgeoning of haute couture and the opening up of female spaces within the theatre. Mata Hari was at this febrile epicentre.

Not only were her performances on stage in demand, but she enjoyed favourable critical comparisons with the modernist dancers Isadora Duncan and Maud Allan, and was courted by haute-couture designers as well. In 1908, she was photographed ‘in a sensational clinging robe of antique blue chiffon-velvet trimmed with chinchilla’ at the Grand Prix d’Automne at the Longchamp races. The same year, the designer Paul Poiret accompanied three of his mannequins in identical Hellenistic gowns to the races, where their dresses, side-split to the knee to reveal coloured stockings, caused outraged comment in the press. Like Poiret, Mata Hari engaged in a cross-media campaign, promoting her skills by appearing at fashionable venues that included the Bois de Boulogne, where she would lease a house in 1911.

This year’s centenary of Mata Hari’s death comes at a moment when the Dutch are beginning to reclaim their compatriot after long being ashamed of her reputation as a tawdry peddler of sex and espionage. A major new exhibition of her life, ‘Mata Hari: The Myth and the Maiden’, will open at the Fries Museum in her hometown of Leeuwarden this October, while the Dutch National Ballet last year debuted a production based on her life and choreographed by Ted Brandsen. Both encourage a more sympathetic view of Mata Hari as a woman who rose above her difficult circumstances to enjoy international celebrity, before she was scapegoated by the French at the end of the war, her life cruelly taken as a symbolic vanquishment of female enemies of the state.

The psychological and historical forces that brought Gretha to the execution grounds of Vincennes have their roots in the sleepy northern Dutch provincial capital of Leeuwarden. Born in 1876 to Adam and Antje Zelle, Gretha briefly enjoyed an indulged childhood. But before she turned 15 her father went bankrupt, her parents divorced, and her mother died. Gretha lived with relatives before enrolling in a teacher-training college in Leiden, where the 51-year-old headmaster could well have abused her, and she left under a cloud of sexual scandal. In 1895, with marriage her only prospect of respectability, she answered a lonely hearts ad in an Amsterdam newspaper, and four months later she married Colonel Rudolph MacLeod, known as ‘Johnny’. She was 18, he 39 – a battle-weary, hard-drinking officer in the East Indies Army, regarded as the black sheep of his aristocratic family.

After their son Norman was born in 1897, the MacLeods set sail for Java, where their daughter Non was born the following year. In the five years that Gretha lived in these islands, she evolved the persona that would become Mata Hari. She appeared in soos (European am-dram societies), dressing up in fantastic costumes and enacting Orientalist tableaux, and observed traditional Javanese court dancers whose precise and fluid movements she would later imitate. Such moments of splendour, however, were rare as their marriage was marked by Johnny’s proclivity for whoring, drunkenness and debt. Then, in 1899, Norman died of an undiagnosed illness. Later, Gretha confessed her fears that Johnny had infected the boy with syphilis. The mercury treatment he received could have caused his death.

The couple separated soon after returning to the Netherlands in 1902. Gretha was awarded legal custody of Non, but with Johnny withholding financial support she struggled to keep her. After losing a battle with the Dutch government for a share of Johnny’s military pension, Gretha headed for Paris, leaving Non with family friends. There she explored her options as a lady’s companion and a teacher of German conversation and the piano. She took rooms, not at the Grand Hotel, but at an English guesthouse in the 14th arrondissement which she found ‘really rather awfully austere’.

Aspiring to work as a ‘house mannequin’ (the precursor of fashion models), she applied to the House of Worth, famous for its sumptuous crinoline gowns and winning Empress Eugenie’s patronage. She also left her details with Redfern and Sons, a British tailoring firm credited with popularising the high-waisted Grecian style of dress. Gretha was optimistic about her chances because, as she explained in a letter to a family friend: ‘I have an extremely good figure.’ Perhaps she was aware, too, that designers invited female buyers and their husbands to inspect the mannequin’s ‘flesh as well as fabric’, a concept that the society couturière Lady Duff-Gordon was already practising in London.

As an artist’s model, designer’s mannequin or on-stage performer, she understood that her body was a commodity for sale

The rise of haute couture crossed over into the theatre, with popular actresses operating as models, and ‘rather than appearing on stage as women who sold their bodies, they became women who sold elegant attire to society ladies’, as the historian Lenard Berlanstein wrote in Daughters of Eve (2001). Theatres were now more welcoming for female audiences as productions were expected to include scenes in which famous designers paid actresses to advertise their luxurious outfits. But while fees and levels of respect for women working in theatre had risen, ingénues such as Gretha were still expected to trade sexual favours for an entrée into the profession.

In December 1903, the director of La Théâtre de Gaîté invited Gretha to audition as principle dancer in the opera Messaline by Isidore de Lara. This might have been an honour, given the theatre’s reputation for avant-garde productions; but as Gretha wrote to Johnny’s cousin Edward, a retired general who took an avuncular role, the director clearly had double intentions: ‘I would have been well-paid, but oh, cousin, I do not dare show myself off in public as a Goddess in a ballet at the opera.’ Commenting on a singing audition the previous month, she wrote: ‘I am having a try at everything and know very well that that position at the Opéra Comique is not because of my voice. I sing well, but not exceptionally so; everything here in Paris is about appearance.’ Edward’s son Donald viewed her position more bluntly: ‘[N]othing is for free in Paris. The greatest actresses and chanteuses “have gone through that” before being able to get ahead. Tutors at conservatoires, theatre managers: they all lay down their singular requirements.’ As an artist’s model, designer’s mannequin or on-stage performer, Gretha understood that her body was a commodity for sale.

However, rather than succumb to the director’s coarse offer, Gretha took her ‘extremely good figure’ to Montmartre to model for a group of Beaux-Arts painters such as Fernand Cormon, Octave Denis Victor Guillonnet and a Madame Bisson. In November 1903, Cormon offered to hire her for 300 francs a month, which was welcome, but his assumption of her sexual availability was not. He told Gretha that she needn’t bother with ‘her attire’ for their first sitting, since he wished to paint her dressed only in ‘Syrian feathers’. Aware of the compromise involved, she assured Edward: ‘To be painted as a model at an exhibition is no lark, but I am unknown and I am not giving out my name and am conducting myself with propriety.’ The following day, Cormon was bemused when she turned down his advances: if she threw off her bourgeois conventions, he said, she could ‘earn money, as much as [I] want’.

For all her hustling, Gretha was often short of money and work, and at such times she’d return to the Netherlands for succour, but Paris always won her back, somehow. In 1904, the aristocrat Ernest Molier hired Gretha for her excellent equestrian skills at his circus in the rue Benouville, where performers included journalists, theatre critics, actors and singers. Like the spaces created by artists’ studios or within the theatre, Molier saw the circus as an escape from the constraints and false posturing of his social class. He suggested that Gretha might have more success as a dancer and, with the encouragement of Henri Jean-Baptiste Joseph de Marguerie, a French diplomat she had met in the Hague, she was introduced to salon hostesses, eager for new acts.

Her first reinvention was as ‘Lady MacLeod’ at the singer Madame Kiréevsky’s salon in February 1905, where her exotic dancing garnered rave reviews. By immersing herself in her memories of the temple dancers of the East Indies, she would become the first European artist to embrace Javanese performance. She distinguished herself from other modernist dancers such as Duncan, Allan or Loie Fuller by drawing authoritatively on life in the East, both in her discussions with admirers and with the press. A cultured performer, she elevated themes such as passion and sexual desire to the level of art, a trend that Lady Duff-Gordon popularised with her mannequins in tableaux with titles such as The Desire of the Eyes, Persuasive Delight, Visible Harmony, A Frenzied Hour, Salut d’Amour, Afterwards, and Contentment.

At Madame Kiréevsky’s, she met the industrialist Émile Guimet who hired her to give evening performances at the Museé Guimet to promote public interest in both Brahmin dancing and Javanese culture. With the loan of jewellery from his collection, and now using the name Mata Hari, the legend was born on 13 March 1905, to rapturous reviews. That year she gave more than 30 public performances in the most exclusive salons in Paris, including the homes of Baron Henri de Rothschild and Cécile Sorel, a famous actress; she appeared six times at the Trocadéro Theatre and at salons such as the Grand Cercle and the Cercle Royal. This high public profile also provided her with important contacts who would further her career, including her agent Gabriel Astruc.

She got 20,000 francs and three bottles of secret ink in return for giving the Germans useful information from Paris

Despite the flurry of media attention, Mata Hari soon realised that the public appetite for the novelty of her Orientalist performance would wane. By 1908, she aired her concerns at a benefit for an Old Actors’ Home where she claimed that she’d be flattered by her imitators, ‘if these ladies’ performances were accurate from a scientific and aesthetic point of view. But they are not.’ Spending above her means and fearing the downward spiral into poverty, Mata Hari ‘slipped’ again, conducting discrete liaisons at the city’s maison de rendez-vous where couples rented rooms by the hour. Well-spoken, beautifully dressed, and an excellent linguist, she attracted rich and powerful lovers who included the composer Giacomo Puccini, the then French minister of war Adolphe Messimy, and a German officer named Alfred Kiepert.

At the outbreak of war in August 1914, Mata Hari was engaged for a six-month run at the Metropol Theatre in Berlin, and was seen in public with her new lover, a police officer named Griebel. Although her liaisons with Kiepert and Griebel would later be used as evidence of her intelligence contacts, the German authorities, for their part, regarded her as a French citizen. Branded an enemy alien, her bank account was frozen and her unpaid seamstress seized her costumes, furs and jewels. Mata Hari managed to escape to the Hague, and soon became the mistress of Baron Eduard Willem van der Capellen who paid for her flat there.

But Mata Hari was restless; the theatres were closed and she found the Netherlands dull after her years in Paris. The stage was now set for her next career move, which, by her own admission, began when Karl Kroemer, the German consul in Amsterdam, contacted her in 1915. As she explained to her French prosecutor, Pierre Bouchardon in 1917, Kroemer gave her the considerable sum of 20,000 francs and three bottles of secret ink in exchange for providing the Germans with whatever useful information she might find in Paris. She agreed, regarding the money as payment for her losses in Berlin, and threw the secret ink into a nearby canal.

In researching Mata Hari’s complicated life, it seems that she stumbled into espionage, assuming that her talent for seduction, which had guided her to fame as a dancer and courtesan, would serve her well. She was profoundly mistaken. Her actions are remarkable for their naiveté, and her inability to grasp that a femme galante in a nation fighting for its survival would be regarded as treasonous. In effect, Mata Hari laid her own trap.

On her first trip back to the Netherlands in 1916, travelling with 10 trunks of luggage, she aroused the suspicion of the UK authorities by giving conflicting reasons for her journey when her ship docked at Falmouth. But her double-dealings and self-contradiction only escalated. When Captain Georges Ladoux, head of the French counter-espionage bureau, offered to employ her as spy in 1916, she failed to explain that she was already working for the Germans. Ladoux’s assignment required that, for a fee of a million francs, she travel to Brussels to seduce Moritz von Bissing, the military general of occupied Belgium, and Mata Hari hoped that this money would allow her to retire from public life. Becoming, in effect, a double agent was a hugely ambitious venture since it demanded she travel across the theatre of war and make contact with a man with whom she had only a brief acquaintance.

There were other signs that Mata Hari failed to understand the essentials of spying. While travelling back to the Netherlands from Paris (using a circuitous war-time route), she passed through Madrid where she sent Ladoux letters en clair through the hotel post and spoke openly with a French officer about an intelligence assignment that involved seducing the German military attaché Major Arnold Kalle. Although Kalle provided her with useful information, he became convinced that she was a double-agent. Kalle sent a series of incriminating telegrams to his superiors in Berlin in a code he knew that the French had already cracked. It was an invitation for the French to arrest her.

Arriving back in Paris in January 1917, Mata Hari must have realised that her grand plans were a fantasy. Two police detectives shadowed her continuously, while Ladoux refused to see her; meanwhile, her debts were mounting and there was no word from her young Russian lover, Vadime de Massloff. When Ladoux finally agreed to a meeting, he refused to pay her for the information she’d gathered from Kalle. On 13 February, five police inspectors and their superior entered her room at the Élysée Palace hotel to arrest her on charges of ‘espionage, complicity and intelligence with the enemy’.

Mata Hari was taken to the Saint-Lazare prison for women, a dark, rat-infested building where sex workers who showed any signs of sexually transmitted diseases were sent for a humiliating ‘treatment’. There she existed in virtual isolation, writing up to six letters a day, to anyone she believed might help to prove her innocence. She pleaded often with her prosecutor Bouchardon who would subject her to 17 interrogations over the next five months, and who observed coldly:

Was she, had she been pretty? Without a doubt … Feline, supple, and artificial, used to gambling everything and anything without scruple, without pity, always ready to devour fortunes, leaving her ruined lovers to blow their brains out, she was a born spy.

Aside from Bouchardon’s preconceived belief in Mata Hari’s guilt, his own recent discovery that his wife had taken a lover fed his anger towards her. As his great-grandson Philippe Collas has written of Bouchardon’s attitude: ‘Mata is guilty because she is immoral. A liberated woman, a sex symbol, a free woman … Mata offended him.’ Worn down after months of interrogation, she confessed to Bouchardon: ‘Today I am going to tell you the truth.’ Despite her protests of loyalty, and her admitting to meetings with Kroemer and Kalle, and to receiving money from the Germans, that moment of transparency would prove her downfall.

She acknowledged that she was a courtesan and admitted to spying: ‘I did what I was able to do for France’

Along with the intercepted telegrams from Kalle to his superiors in Berlin, Ladoux and Bouchardon had the opportunity, during a national mood of ‘spy psychosis’, to brandish an enemy agent, caught red-handed. The case proceeded to a court martial, held in camera at the Palais de Justice on 24 July 1917. Mata Hari, dressed in a tricorner hat, a dark-blue coat and low-cut frock, unaware that she was fighting for her life, faced a jury of seven officers. She acknowledged that she was a courtesan who regarded a military man as ‘a sort of artist’ whose nationality was unimportant to her, and she admitted to spying – not for the Germans but for the republic: ‘I did what I was able to do for France.’

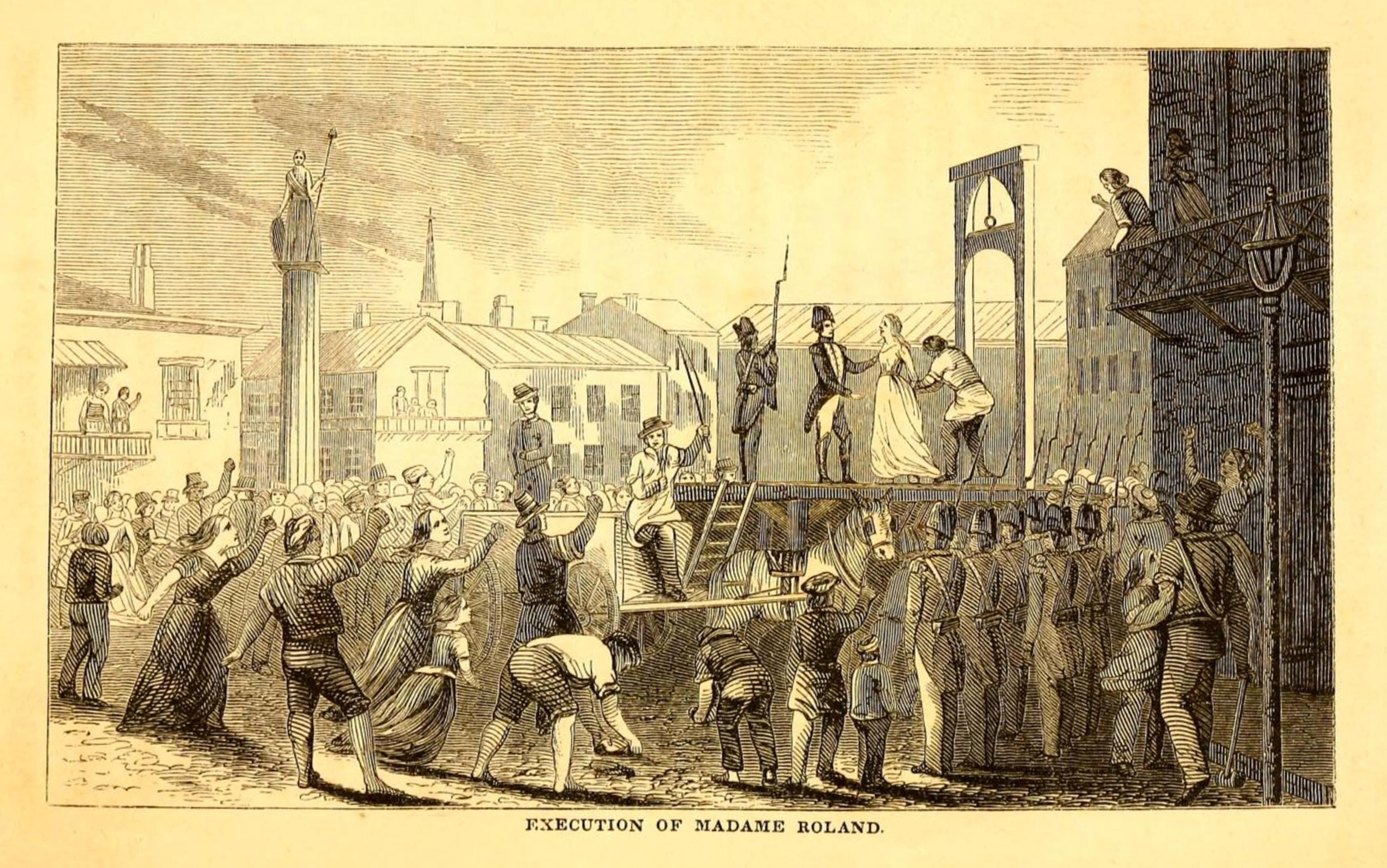

The judges passed a sentence of death, and before daybreak on 15 October 1917 she was driven to the execution grounds at Vincennes. One witness described how she refused a blindfold at the stake and then: ‘Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her.’ A non-commissioned officer then walked up to her body, pulled out his revolver, and shot her in the head.

Since that fateful day, more than 250 novels and biographies have been published about her, the first appearing weeks after her death, in some 60 languages. Heavily fictionalised versions of her life were popularised from the 1930s on, with films starring Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich, and by Alfred Hitchcock with Notorious (1946) and North by Northwest (1959). She has embodied the role of femme fatale, even inspiring Second World War agents such as Violette Szabo, and creating an obstacle for others such as Josephine Baker.

Before the military archives at Vincennes began to open up in the 1960s, the Mata Hari of popular culture was guilty as charged – a ‘half-caste spy’ who ‘met a well-deserved fate’. But when the files were opened, revealing how little evidence her prosecutors possessed, along with details about her tragic early life, another Mata Hari emerged. She might have been exploited and abused by men throughout her life but for a brief, glittering moment, she boldly threw the male gaze back at her spectators and shone upon the world’s stage.