I was too young to bartend and too short to pass hors d’oeuvres. Dressed in black slacks and a white oxford shirt, I set tables, cleared trays, and washed dishes. I was 14, just old enough for a work permit, and it was my first night catering.

The wash station was far from the tent and the main house, tucked where none of the guests could hear us scraping plates or see us using the garden hose to fill water pitchers. A few hundred guests multiplied into a few thousand forks, knives, spoons, plates, water glasses, wine goblets, and champagne flutes. It was a harried night, one I spent hoping that I wouldn’t fall into any holes in the uneven yard while carrying trays in the unlit darkness. I hoped, too, that there might be some reason for me to enter the main house.

I had known about this estate since childhood. Wye House is one of the oldest homes on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, and among the most famous plantations in America. Built in the late 18th century, the main house is a grand, two-storey structure that bridges late-Georgian and early-Federalist architecture. Its agricultural fields, orchards, and gardens once sprawled across 42,000 acres. It would be easy to mistake Wye House for Tara, the wind-swept, war-torn estate in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. Even now that the property has dwindled to 1,300 acres, the pale-yellow plantation home is still an island in a wild green sea.

Thousands of slaves built this house, cultivated these fields, somehow managed to grow bananas, broccoli, oranges, and even ginger root in the plantation’s orangery, which is still heated and irrigated by the original 18th-century pipes.

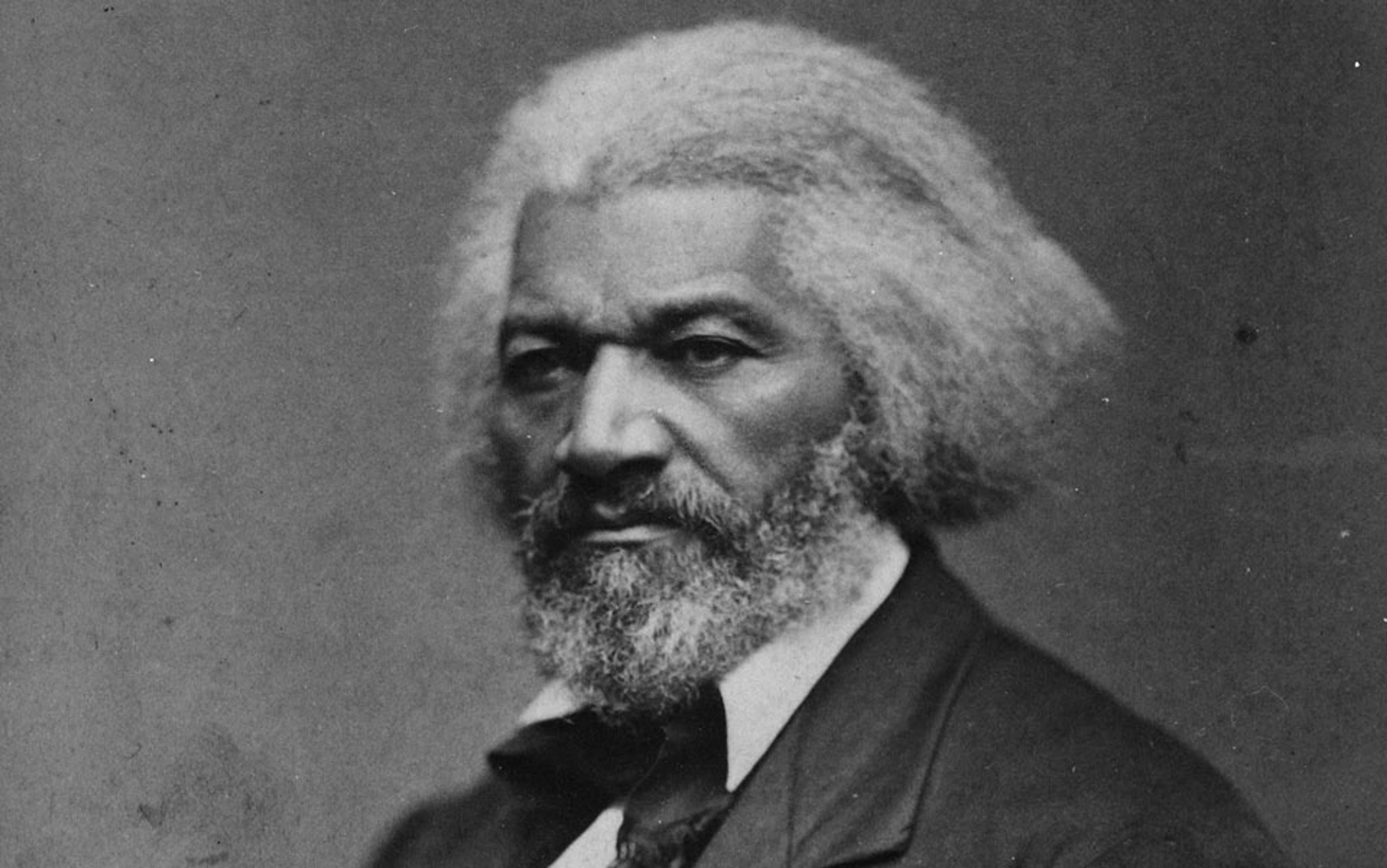

Of them all, only one is known to me. For two years, the young Frederick Douglass was a child slave at Wye House.

I know of him because, after years of slavery, he escaped and wrote an autobiography: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845). It is a beautiful book that I first read as a cheap paperback with a font so small and margins so narrow that when I try to read that copy again as an adult, it strains my eyes and causes a headache. I read that book the way one reads an adventure story, transfixed by the chapters that carried Douglass far, far away from the Eastern Shore.

Douglass is Talbot County’s most famous native son. Although he became one of the most famous black men in America and a celebrity around the world, Douglass was born in a tiny, now nonexistent village called Tuckahoe. It’s not far from where I was born at Easton Memorial Hospital or where I was raised in a map-dot town called Cordova.

Talbot is one of nine counties on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, whose western border of meandering shorelines is carved by fresh-water tributaries and the brackish Chesapeake Bay; whose eastern border is formed by the Delaware, and whose northern and southern boundaries are Pennsylvania and the Eastern Shore of Virginia respectively. These counties were settled in the 17th century and divided into plantations, like Wye House, that grew corn, tobacco, and wheat.

More than tragedy or romance, history is filled with irony. Just down the road from Wye House is a small hamlet called Unionville that was settled by former slaves and free blacks who returned to the Eastern Shore after the Civil War. The land was leased to the community by a Quaker family, abolitionists who abhorred their slave-owning neighbours and sent one of their sons to serve as captain of a black regiment in the Union Army. Almost all of the 18 Union soldiers whose names are carved on tombstones in the Unionville Cemetery were first listed as property in inventories at Wye House. These men returned from the War and settled only a few miles from the plantation where they were once slaves.

Take one left off Unionville Road and arrive at Wye House; take another, and arrive at the Hanging Tree. The trunk of this oak tree looks like an outstretched arm bent at the elbow: it rises two-dozen feet in the air, then bends at a perfect right angle before rising another two-dozen feet. As a teenager, I can remember driving to this haunted spot and waiting for midnight when the ghosts of the hanged were supposed to appear. It’s the sort of ritual repeated unthinkingly in an area where Confederate flags still fly on flagpoles, Confederate decals adorn the bumpers and back windows of pickup trucks, and Confederate uniforms and belt buckles hang in ornate frames in living rooms.

Maryland was a border state, but the Eastern Shore has always been secessionist. The Talbot Boys, the regiment from Talbot County that fought for the Confederate States of America, are memorialised with a 13ft statue on the Courthouse Green in Easton. Erected in 1916, the Confederate war memorial features a life-size, youthful standard-bearer who stands vigilant atop a broad granite base. The names carved on the base of that monument are locally familiar, whether or not you know Civil War history; they are the names of streets and towns around the Eastern Shore: Tilghman, Ewing, Goldsborough, Thompson, Wrightson, McDaniel, Tunis, and Lloyd.

By contrast, for much of the 20th century, the only public acknowledgement of Frederick Douglass was a small roadside marker along Maryland Route 328:

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, NEGRO PATRIOT: ATTAINED FREEDOM AND DEVOTED HIS LIFE AND TALENTS TO THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY AND THE CASE OF UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE. VISITED ENGLAND IN 1845 AND IN 1859. WON MANY PROMINENT FRIENDS ABROAD AND AT HOME. WAS US MARSHALL FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AND US MINISTER TO HAITI. WAS BORN IN TUCKAHOE, TALBOT COUNTY.

Placed by the State Roads Commission, you will miss it if you blink after crossing the bridge over the Tuckahoe River. The village of Tuckahoe no longer exists, so the marker sits by the side of the road without explanation, far from any extant town.

Talbot County’s is the least remarkable of any of the memorials I’ve seen for Douglass. I have found the abolitionist everywhere else: in parks, playgrounds, and schools across the country and around the world. Years ago in Belfast, after taking a cab down the loyalist Shankill Road and back up the republican Falls Road, I looked at the political murals on the Peace Line and saw there a portrait of Douglass, his birth and death dates clearly marked.

Frederick Douglass mural in Belfast Northern Ireland. Photo courtesy NornIronphotos

To the left it read: ‘Inspired by two Irishmen to escape from slavery Frederick Douglass came to Ireland during the famine. Henceforth he championed the abolition of slavery, women’s rights and Irish freedom.’ To the right it quoted Douglass: ‘Perhaps no class has carried prejudice against colour to a point more dangerous than have the Irish and yet no people have been more relentlessly oppressed on account of race and religion.’

I remember reading those words and wondering how a prophet so honoured by the world could be so forgotten by his hometown. I am not surprised by all the places where I have found Douglass around the world; I am saddened that it is so hard to find him in Talbot County.

Talbot County, like so much of America, has an uneasy relationship with its past; and Easton, like so many small towns, has no idea what to do with its uncomfortable history. In 2004, a few locals proposed honouring Douglass with something more than a road sign. They asked the Talbot County Council that Douglass be given a monument on the Courthouse Green like that of the Talbot Boys.

Fred’s Army, as they came to call their group, was told that the Green was reserved for veterans of past wars, the only two statues there being dedicated to the Talbot Boys and to the veterans of the Vietnam War. For weeks, letters to the local newspaper seethed hatred and hurt not cured, much less calmed, in the century since Douglass’s death. Members of the local chapters of the Vietnam Veterans of America, the American Legion, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars all spoke against the monument. Members of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People spoke for it.

Letter by letter, speech by speech, the two sides divided in ways uncomfortably similar to those of a century before. Statue supporters challenged any definition of veteran that allowed for a public memorial to the Confederacy but disallowed a monument for Douglass; those opposed to the statue insisted that military service be the sole criteria for public memorials on the Green, and that Douglass would be better honoured with a memorial at a school or a library. The opposition called itself patriotic; the supporters of the monument called them racist.

After weeks of debate, the Talbot County Council, in a narrow three-two vote, approved the monument. That vote, in 2004, was followed by years of delay and continued debate over the design, height, and exact placement of Douglass on the Courthouse Green. A policy was created that required so that any new statue on the Green not exceed the dimensions of the other statues, meaning quite literally that Douglass could stand no taller than the Confederate standard bearer.

Finally, in June of 2011, a statue was installed and dedicated. One hand raised mid-oration, Douglass looks as though he could be chastising the Confederate monument. His life-size bronze statue finally offers a challenge to the Talbot Boys. For nearly a century, the Lost Cause was more honoured than the Just Cause, a fear Douglass had himself articulated in the years after the Civil War.

At Arlington National Cemetery in 1871, Douglass had observed: ‘We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.’ In 1894, at a Memorial (then ‘Decoration’) Day address in New York, his language was even sharper: ‘Fellow citizens, I am not indifferent to the claims of a generous forgetfulness but whatever else I may forget, I shall never forget the difference between those who fought for liberty and those who fought for slavery.’

Douglass experienced abuse that was worse than any he had ever witnessed, but he also had the profound awakening that led him to escape slavery

Even though the military conflict had ended, the fight for the narrative of the Civil War had not. Douglass lived long enough to see the gains of Reconstruction disappeared; by the time he gave that speech in May 1894, the Supreme Court had already ruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional. He was right to intimate that racial strife had not ended with emancipation, and that the Lost Cause and the Just Cause would be confused.

For most of my childhood, the two seemed indistinguishable. The legacy of the Civil War was shared sacrifice, whether your family or your state had fought for the North or the South. The Talbot Boys were veterans, not of a partisan cause, but a national conflict, and you bowed your head when you passed them without thinking. You didn’t care that you lived within two hours of the nation’s capital, but you were proud to live south of the Mason-Dixon Line. You visited the Hanging Tree no matter how uncomfortable you found such a ritual. Such behaviour was not limited to locals or natives: in 2003, the year before the controversy over Douglass’s memorial, then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld purchased a vacation home in Talbot County. He bought Mount Misery, the farm where Douglass experienced the most brutal beatings of his life.

While it was at Wye House that Douglass first saw ‘the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery,’ it was at Mount Misery that he experienced it for himself. Owned by Edward Covey, the farm was where slave owners sent their property for ‘breaking’. At Mount Misery, Douglass was subject to abuse worse than any he had ever witnessed, but he also had the profound awakening that led him to escape slavery.

After eight months working under Covey, on a hot summer’s day in August of 1833, Douglass collapsed from heat exhaustion. Covey attempted to punish the slave by beating him with a wooden plank. Douglass escaped and tried to inform his owner of Covey’s gross abuse, but his owner ordered Douglass back to Mount Misery. For two hours on his return, slave driver and slave fought. ‘This battle with Mr Covey,’ Douglass wrote in the autobiography, ‘rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood … [it] inspired me again with a determination to be free.’

Less than four years later, Douglass escaped. In September of 1838, he boarded a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland; from there, he took a ferry across the Susquehanna River to catch a second train to Delaware; at Wilmington, he travelled by steamboat to Philadelphia. In less than a day, Douglass was safe in New York, and by the end of the month, he would be married and settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Douglass first told his remarkable story at small gatherings of abolitionists around Massachusetts. Within a few months, he was invited to address the state’s Anti-Slavery Society’s annual convention. By 1845, he had published his first of three autobiographies, which became an immediate bestseller; that same year, he sailed to England for a two-year speaking tour to promote the cause of abolition.

‘Time Makes All Things Even’ is the title of a chapter in Douglass’s final autobiography. While he worried greatly that the evenness of time would soften the realities of the Civil War, this chapter recounted his four reconciliatory returns to the Eastern Shore as a free man.

The first took him to St Michaels, where he met with his former master, Captain Thomas Auld. Douglass had written Auld an incredible letter many years before, published in an anti-slavery newspaper. ‘I entertain no malice towards you personally,’ Douglass wrote, ‘I am your fellow man, but not your slave.’ By the time of their meeting in June of 1877, Auld was on his deathbed. ‘Tenderly Douglass grasped the palsied hand of Captain Auld,’ The Washington Star reported: ‘addressed him as old master, and manifested emotion creditable alike to his manhood and his heart.’ The second return, in 1878, took Douglass to Easton, where he gave speeches at two black churches and on the Courthouse Green. ‘This visit was made interesting to me,’ he wrote ‘by the fact that 45 years before I had … been dragged to Easton behind horses, with my hands tied, put in jail, and offered for sale.’

The third, six decades after first witnessing ‘the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery’, was a return to Wye House.

The fourth, in March of 1893, fewer than two years before his death, was supposedly to look for possible retirement homes, though Douglass would ultimately die of a heart attack in Washington, DC, and be buried with his wife in Rochester, New York.

Is the sin of racism erased if we destroy the memorials that preserve it?

All four returns to the Eastern Shore were marked by forgiveness. Douglass’s private journeys are illustrative of the journeys he expected the nation to make through its collective history. He refused to deny the horror of any these places, but equally he would not repudiate any of the individuals connected to them. He met with his former owner Captain Auld; he shook hands and walked with Howard Lloyd, great-grandson of the Colonel Lloyd who had owned Wye House during his enslavement.

Douglass understood that history was not only life, but narrative. Nowhere is this belief — that the stories we tell are what shapes the past — clearer than in the campaign he waged against the narrative of the Lost Cause. Douglass spent the last three decades of his life arguing for sharp distinctions ‘between those who fought to save the Republic and those who fought to destroy it’. A century later, those distinctions had not only faded in Talbot County, but the Lost Cause had overtaken the Just Cause.

So how are we to tell the stories of our past, especially in little towns like Easton? Is the sin of racism erased if we destroy the memorials that preserve it? The United Daughters of the Confederacy alone built hundreds of monuments to the Confederacy: these memorials dot cities and towns around the South, but we cannot destroy them any more than we can erase the history they mark. In Talbot County, that history lives not only in the granite statue for the Talbot Boys, but in the walls of Wye House, the trunk of the Hanging Tree, in place names and family trees. To remember, as Douglass demanded, ‘the difference between those who fought for liberty and those who fought for slavery’ is to remember both sides.

Those who opposed Douglass’s memorial wanted black history to remain invisible, banished to small road signs on rural roads. The other side sought to balance the public symbols of the past by placing a native abolitionist on the green. Now the shame of the Talbot Boys, that young rebel standard-bearer, stands forever opposite the glory of Frederick Douglass, that tall abolitionist poised in triumphant speech.

Without our stories, there is only irony: a rebel soldier and a black abolitionist. With them there is this: the story of the slave who left but returned a free man, and the soldier whose courage was great but whose cause was immoral; the romance of Unionville a little way down the road from the tragedy of the Hanging Tree.