Dover Priory, 16 November 1535: at a modest monastic establishment on the edge of one of England’s main working ports, the nearest to the continent of Europe, the abbot signs a ‘deed of surrender’, turning over the establishment and all its property from the Church to the king. For centuries, since its foundation in the 12th century, the priory had served the needs of its small community of monks, whose main purpose was to work a small parcel of common lands, and to pray (in Latin, ora et labora). Music-making beyond that necessary for the daily cycle of prayer fit neither category, so the priory’s brothers employed musicians from the neighbourhood, among them the young Thomas Tallis (born c1505), who served as their organist and trained young boys in music in the priory’s school. Perhaps Tallis would have been working with the boys, or playing music at one of the liturgical hours with the monks, when the king’s commissioners arrived to turn out the brothers, and seized the priory’s buildings and land in the first phase of Henry VIII’s dissolution of England’s monasteries.

Or perhaps, over a period of months, the priory’s rich communal life just faded away. The monks, their employees and the boys would have known the end was coming: officials had been snooping around the priory for months, assessing the value of its property and the behaviour of its residents. Yet the sudden change would have been a shock. Musically, it meant significant change to the centuries-old cycles of bell-ringing, song and prayer attuned to the natural rhythms of worship and agricultural labour at the centre of monastic life. In the world of the medieval monastery, sound was a constant and meaningful presence, a fundamental part of understanding one’s place in the world. People knew when and where they were from the sounds of the bells; the emotional immersion of communal singing structured their relationship with God.

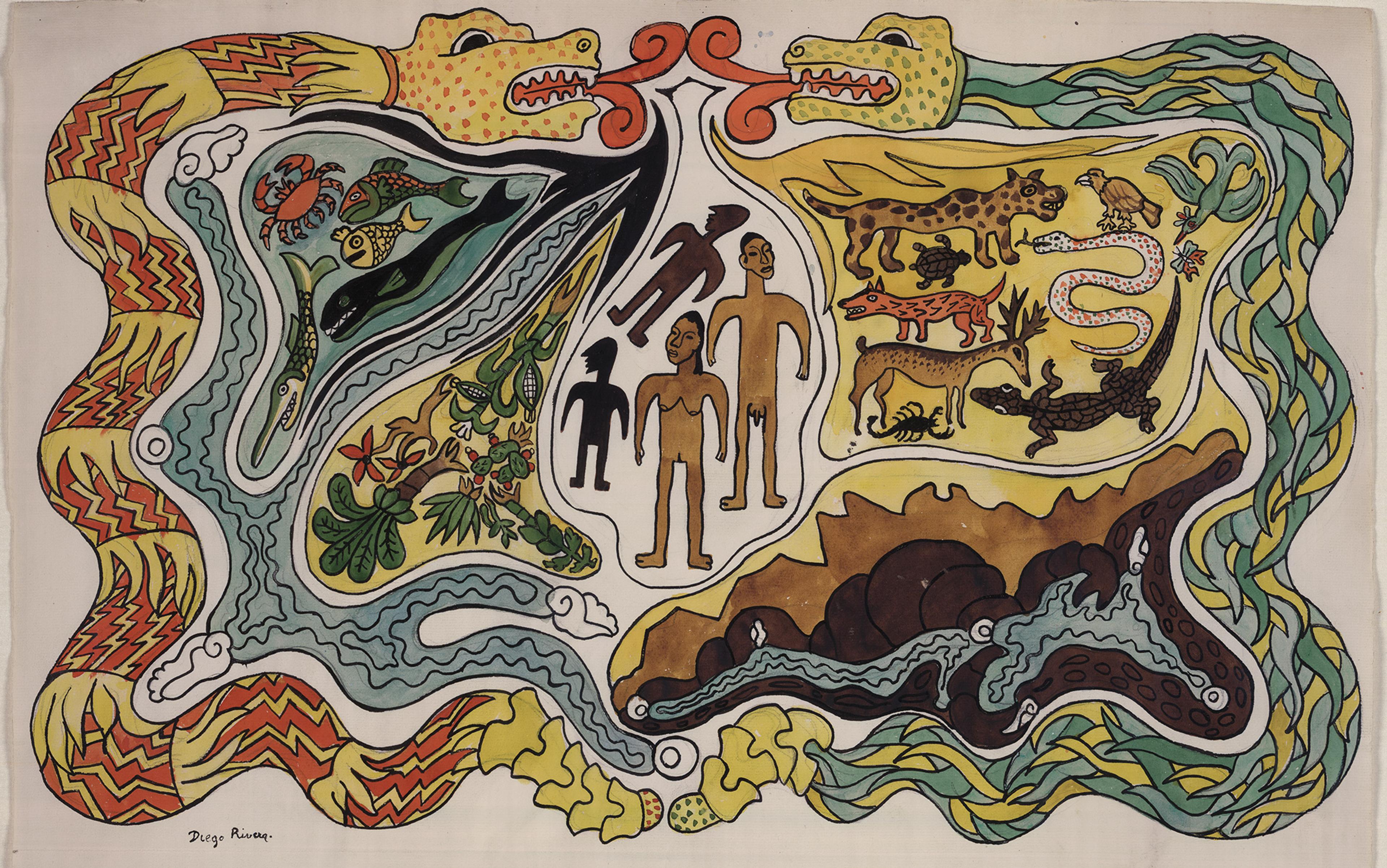

The soundscape of monastic life was common property for monks (and nuns), for people in their care and for those with whom they worked. In a sense, human-generated sounds would have been indistinguishable from those of the natural world: such distinctions might have been incomprehensible to the 16th-century mind. A few generations after the dissolution, William Shakespeare would write musically in Sonnet 73 of a late-autumn scene, of ‘bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang’. The sounds of nature, in other words, were not separate from those of society, because neither concept, nor their perception as a dichotomy, had yet crystallised in Western thought.

The Ruins of Kirkstall Abbey at Night (c1799) by William Turner. Courtesy Tate Britain

In place of this pair of opposites, as more than one historian has suggested, stood a singular ‘web of life’. This unitary, rather than dualistic, perception of how the world worked meant that, in centres of medieval learning in the West, music figured as one of the four key numerical arts (the ‘quadrivium’) alongside mathematics, geometry and astronomy. Five centuries later, music is mostly considered an artistic activity outside of the realms of science, and thus falls on the ‘social’ side of the nature/society divide. But in the world of Tallis’s youth, to understand music was to understand nature, to live in it.

As Tallis got older, music and sound were to take on new meanings. For all that dissolution meant the displacement of a familiar sound world, it also meant, for some, the opportunity to profit from sound in new and different ways. For figures like Tallis, it was a dramatic but ultimately manageable twist in an individual biography. The young composer-musician moved soon after to a much larger establishment, Waltham Abbey in Essex, 14 miles from London, and from there – after it was dissolved in 1540 – to a glittering career as a court composer for Henry VIII and his children Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I, moving with suppleness through musical styles even as political and religious turbulence swirled around him.

The Family of Henry VIII (c1543-47), unknown artist. On display in Hampton Court Palace and courtesy the Royal Collection

A primary context for the global 16th century as a whole, as well as for Tallis’s working life from its beginnings at Dover Priory, was enclosure, the seizure of previously common property for private profit. The enclosures that went with the dissolution of the monasteries were part of a huge world-historical process that included the first colonial expansions of European states, and initiated a process of rapacious extraction of the globe’s raw materials that continues today. The economy of extraction – you might also call it unbridled ‘capitalism’ – bred more extraction, and with it more destruction of the environment and, as was the case with dissolution, of previous lifeways. Under the sign of extractive capitalism, ‘nature’ becomes a passive object that must be exploited (also to the point of destruction) for the good of ‘society’.

Tallis was a man for the new era. He was a professional musician who worked for a salary. His career depended on clever management of political patronage in turbulent times. This management is clearly visible in his employment history and literally audible in his music, which moved from brilliant reinterpretations of the latest continental Latin Catholic polyphony to much more straightforward English-language hymnody (as required by the demands of the new Anglican Church), then back again to more ornamented Latin-texted music in the short interregnum of the Catholic Mary I before landing somewhere in the middle under Elizabeth I, a young Protestant queen whose court was initially dominated by powerful Catholic families.

This mutable aspect of Tallis’s career and compositional approaches under four English monarchs might be understood as a search for the most efficient way to release the right (eg, most remunerative) kinds of creative musical energy in order to capture some of the excess riches that enclosure brought for its beneficiaries. These riches included those the Tudors acquired through the dissolution, the beginnings of the British imperial project through the Protestant plantations in Ireland, and also the wealth that had begun flowing to northern Europe from the rest of the world. The latter came to England with Tallis’s erstwhile Catholic patron Mary’s brief marriage to Philip II of Spain, whose possessions, when he succeeded his father Charles V, spread from Madrid through the Americas.

To sing Thomas Tallis and William Byrd was to sing ‘unlawfull songe’

In return for these wages, Tallis created much extraordinary music. It would not be too far-fetched to think of the ‘retention’ arrangements Tallis was offered at the court of the young Elizabeth I, which included the novel right (together with his younger colleague William Byrd) to print court music for his own profit, as a kind of musical enclosure, a privatisation of formerly communal intellectual property. Indeed, a few years later, Tallis was granted rents from actual enclosure, from Crown land, after he complained that his printing privilege no longer brought what it had.

That is not to say that Tallis didn’t pay a heavy price for living when he did. As Peter Phillips – the leading Tallis performer-scholar of our time, and director of the Tallis Scholars – has pointed out, Tallis was the only major composer of his generation in England whose long life and, one assumes, diplomatic skill meant that he kept composing when the political and religious winds changed. We don’t know the truth about Tallis’s own religious convictions, although scholars have long assumed that his continuing commitment to Latin-texted music tells its own story. We do know that, at several points in his career, being too close to the old Catholic religion would have put him in mortal danger.

Research by the music historian Jeremy Smith has uncovered just how close Tallis came to serious trouble with the Tudor authorities. Just a year after Tallis’s death, Edward Barker, an official at Elizabeth’s court charged with investigating Catholic plots to replace the queen with her cousin Mary Stewart, turned up evidence that one of England’s leading aristocratic Catholic families, the Pagets, had five years earlier kept a ‘secrete’ choir in their private residence to sing ‘direges [dirges] and such lyke stuffe’. In the usage of the time, the word ‘direges’ referred to the Catholic Office of the Dead, the implication here being that the secret choir was singing mourning music (‘gallows music’) for the English Jesuit Edmund Champion, who was executed for treason in 1581. The leader of the choir, the musician Henry Ediall, protested under interrogation ‘that he … did use himself to singe in his lordshipes howse songes of Mr Byrdes and Mr Tallys, and no other unlawfull songe.’

The reference has to be to Tallis’s joint publication with his junior colleague Byrd (who really was a recusant Catholic) of Cantiones, quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur (1575) or ‘Songs, which by their argument are called sacred’, the very ones for which the two composers were granted royal printing privileges. Ediall disappears after the interrogation from the historical record, but his testimony – and his possible slip of the tongue that to sing Tallis and Byrd was to sing ‘unlawfull songe’ – gives some indication of the high stakes attached to music in the feverish atmosphere of the Tudor courts.

To our ears, Tallis’s music seems to emerge from the alluring mists of a lost medieval England, for instance as it does from the pastoral fog of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s beloved classic Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (1910). There it comes across as the sound of an ancient English landscape: something natural, beyond specific time and place. From a critical perspective, we might instead hear in Tallis something jarringly new, a product of a more complex story, behind and around his music’s sonic enchantments. We hear the sounds of a new regime of extraction, in which nature is there to be exploited, and destroyed, for profit: and, along with it, the sounds of the terrible price that new regimes of enclosure exacted from everyone they touched.

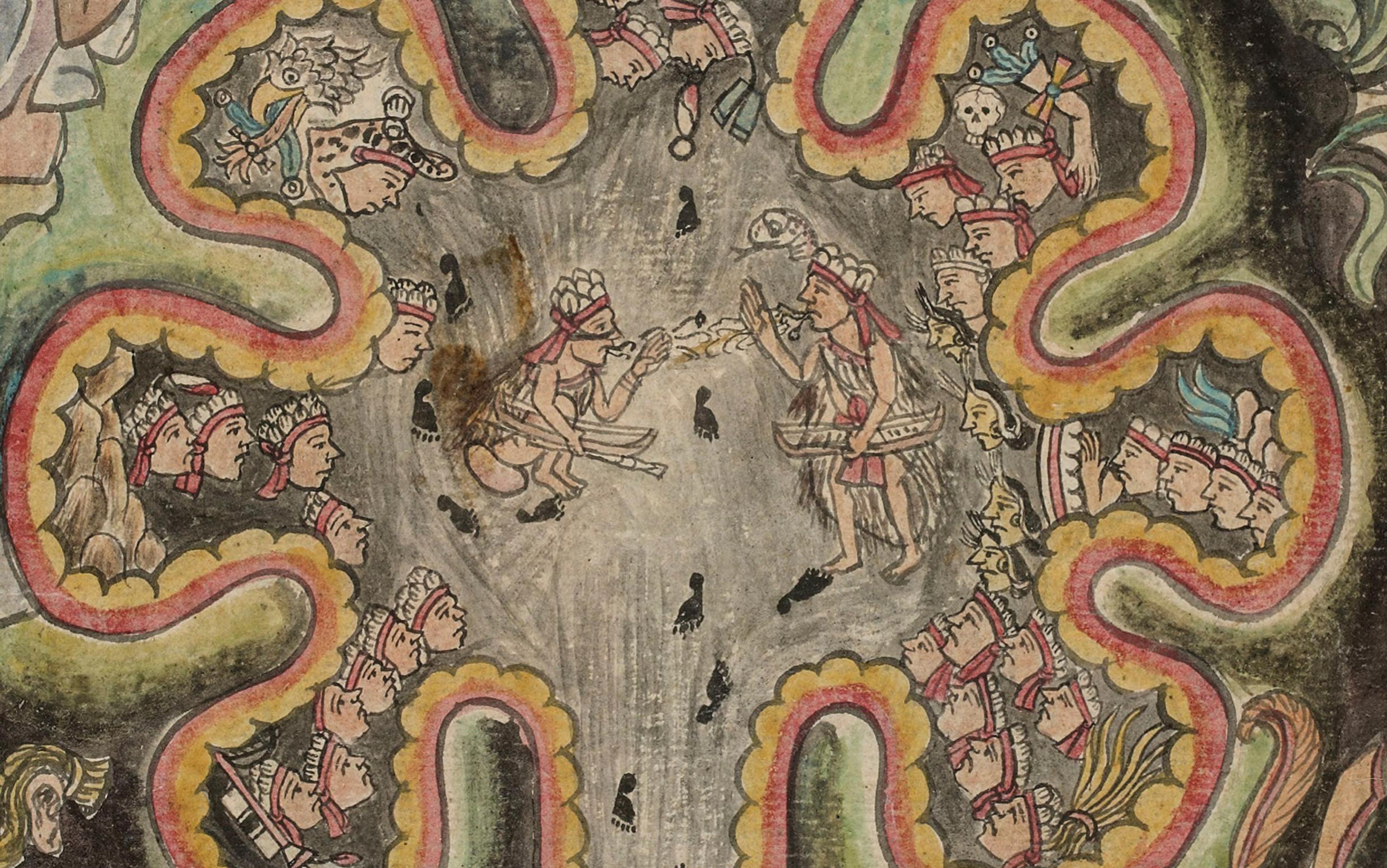

Mexico City, New Spain, 3 September 1607. Don Domingo de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin, an educated and privileged Indigenous scholar, fluent in both the conquerors’ Spanish and his native Nahuatl, writes in his annals. That September day, he recorded the disturbing sound of church bells. It has been raining for weeks, and the city, then still an island in a large lake in the valley of Mexico, is filling with water. The bell-ringing, which started at the cathedral a few blocks to the south, began in the morning: it sounded ‘like when excommunication is promulgated, very mournful, frightening and startling’. Nearly 500 years later, Chimalpahin’s extensive Nahuatl text offers one of the best sources we have, written from the perspective of an intercultural observer with a foot in both worlds of experience, on life in the immediate generations after the Spanish conquest. Chimalpahin was a descendant of an aristocratic family from the Chalca people, one of whom was a famous musician. That means what his trained ears captured can be trusted. What he heard was the sound of anthropogenic natural disaster.

Tenochtitlán, the great city of the Mexica or Aztec people, was surrounded by water and always subject to flooding. The city’s rise to the position of one of Mesoamerica’s dominant urban areas in the 14th century CE, however, made things worse. After its conquest, destruction and rebuilding at the hands of the Spanish in the years following their defeat of Tenochtitlán’s Mexica rulers in 1521, the flooding continued as before, and was exacerbated by changes that the Spanish made to the built environment, including the widening of raised paths on dykes to accommodate horse traffic and the filling in of drainage canals to allow more space for construction.

Map of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán from 1524. Courtesy Wikipedia

By around 1600, however, the inhabitants of the city began to experience a more profound, troubling and destabilising deterioration in their relationship with their watery surroundings. Beginning soon after the conquest, the Spanish authorities began to enclose woodlands in the hills and mountains around the Valley of Mexico and force Indigenous people to cut down trees on this land for use in building projects. The results of this deforestation (all too easily anticipated from today’s perspective) included erosion, due to the breakdown of soil, and even greater flooding. By the 1550s, the first plans for a desagüe (drainage) of much of the valley had been prepared but then abandoned. The rainy season of 1607 – in Mexico City, winters are dry but summers are wet – was more intense than usual. The results were calamitous. Chimalpahin’s own parish church of Santo Domingo, of which he, in the tradition of Nahua annalists, was intensely proud, was reduced to ‘a very sad sight; it was just a pond.’ The local response – completely understandable from today’s perspective – was mitigation, to raise the floor of the church above the rising waters. Around the city, other church communities did the same. But soon the authorities were convinced that a massive desagüe was required if the city were to be saved.

Excommunication was the ultimate form of social control … It meant social death

Chimalpahin’s ‘mournful, frightening and startling’ bells thus heralded a massive transformation in the Valley of Mexico’s natural environment, a human intervention meant to make a huge city work where none really belonged, which continues today on a scale unimaginable in 1607. Thanks to Chimalpahin’s extraordinary position as mediator between Indigenous and European histories, it is possible to reconstruct with some accuracy – just as we might for Tallis in the months before Henry’s commissioners arrived in Dover – what he heard all around him, day and night, in September 1607: ‘there would be ringing everywhere because of the cloudbursts, and the ringing went on that way in Mexico all during the said month of September.’

A contemporaneous clue to the actual sound of excommunication is to be found back in England, in Christopher Marlowe’s play Doctor Faustus (c1592), wherein the scholar invites the pope and his cardinals to ‘curse [him] to hell’ with ‘bell, book, and candle, candle, book and bell’. Without going too deeply into the complex layers of politico-religious meaning in Marlowe’s play, it is enough to note the repetition in the lines, which echo the chanting of the Maledictus Dominus, and perhaps the clangour of bells themselves, in the Catholic rite of excommunication; they are also reminiscent of the power the Elizabethan secret policeman Edward Barker ascribed to the secret Catholic ‘direges’ sung in the home of the traitorous Paget brothers. Britons of Marlowe’s generation would have known these chants in the aural memory of their youth, just as his contemporary Chimalpahin would remember the pre-conquest Nahua music sung to him by members of his grandparents’ generation in his own childhood.

The excommunication scene in Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus offers a ghastly hint to what Chimalpahin meant when he wrote that the flood-warning bells, in their ‘mournful, frightening’ repetition, sounded like those used when ‘excommunication is promulgated’:

Enter all the Friers to sing the Dirge.

Come brethren, lets about our businesse with good devotion.

Sing this.

Cursed be hee that stole away his holiness meate from the table.

Maledicate Dominus.

Cursed be hee that stroke his holinesse a blowe on the face.

Maledicate Dominus.

Cursed be he that tooke Frier Sandelo a blow on the pate. male, &c.

Cursed be he that disturbeth our holy Dirge. male, &c.

Cursed be he that tooke away his holinesse wine.

Maledicate Dominus.

Et omnes sanctis Amen.

Chimalpahin knew what the rite of excommunication sounded like because we can be almost certain that he had witnessed it first-hand. Excommunication, the expulsion from the Christian religious community, was the ultimate form of social control, used to discipline Indigenous people at the disposal of Mexico City’s church authorities. It meant social death. The threatening repetition of the flood bells thus invoked in Chimalpahin the worst fear he and his community, already decimated by years of deadly epidemics and traumatised by humiliating defeat at the hands of the Spanish, could possibly experience: the loss of what was left of their humanity (and most likely their lives). Nothing less than this fear is literally audible in his description of the bells of September 1607.

Nor were the bells the only sounds of ominous global processes, human-made changes to geology and economy, that Chimalpahin heard. In 1612, he was witness to a crackdown on Mexico City’s Black population that culminated in the brutal public execution of 35 enslaved people accused of conspiring to overthrow the colonial regime and install an African kingdom (a monarchía africana) in its place. The plot turned out to be imaginary, and the executions a product of rulers’ ethnocentric misunderstanding of an unfamiliar cultural ritual. The executions in 1612 were the brutal final act of a series of events going back to 1608, when Spanish authorities became alarmed at carnivalesque activities on the part of their slaves. The most alarming was probably a ‘mock coronation’ – held by members of the city’s enslaved African population during Christmas Eve celebrations – of a sort that echoes throughout the African Diaspora.

By the turn of the 17th century, Mexico City had a substantial Black population. The enslavement of Africans as a source of cheap labour had followed on almost immediately from the ‘discovery’ of Mesoamerica: the Spanish and Portuguese were already using enslaved people from the coastal zones of Africa in the early plantation economies of Atlantic islands such as Tenerife. The realisation in the mid-1500s of the enormous profits to be had from exploiting the Americas led to the massive expansion of such economies, particularly in areas where European-introduced diseases had already killed much of the Indigenous population. Thus, there are Africans in New Spain from very early on in the colony’s history. In the capital Mexico City, they worked primarily as domestic servants, and employing them was a badge of social distinction for those Spanish families who could afford to. By around 1600, particularly in the wake of decades of high mortality from epidemics among the Indigenous population, they made up a substantial portion of the city’s population.

Black cultural practices, novel in the Americas, would have been hard for any observer to miss, especially if they were sonorous. This is probably why the Spanish inhabitants took notice of the mock ‘coronation ceremonies’ that undoubtedly featured drumming and other forms of African musical expression along with repertoires of bodily movement that would have been unfamiliar or even unnerving to both Spanish and Indigenous observers. Confirmatory ‘echoes’ of this cross-cultural observation – or misconception – exist in both the corn-shucking ceremonies of the 19th-century North American Deep South, in which competing gangs of enslaved workers would replicate harvest celebrations by crowning the plantation owner ‘king’ and parading him in state, literally ‘Singing the Master’, and in the 18th-century Pinkster (Pfingster: ‘Pentecost’) celebrations of Afro-Dutch New York State, when an African ‘Pinkster King’ would preside over the carnivalesque festivities.

Like Chimalpahin, we feel that the water is rising threateningly all around us

Other, more ominous historical parallels appear even closer to the Mesoamerican moment: the dance historian Paul Scolieri describes ceremonial pageants in the 1530s re-enacting the Conquest in which Hernán Cortés himself played the ‘Christian commander’, while defeated and newly baptised Indians played Dominican missionaries. Scolieri rightly calls these ‘rituals of “humiliation” … through which Indians repeatedly performed their [own] subordination.’ Chimalpahin’s moving description of the execution of the Black ‘plotters’ includes a report of their cries ‘to their redeemer our lord God’. These cries, and the tolling of the flood bells, sounded the arrival of Western technologies of extraction and enclosure in the Valley of Mexico.

These sonic stories should resonate with us today. We too feel that many of us are called upon to navigate in our professional lives through times of profound political instability, fight entrenched prejudice, and, like Chimalpahin, that the water is rising threateningly all around us. In other words, like these historical witnesses, we too live under the sign of anthropogenic climate change, and of its divide between society and nature. One of the most profound consequences of this divide has been the assignment of whole swathes of humanity (people of colour and women) to the ‘nature’ side of the equation, on the ‘scientific’ grounds that such people are different, a lesser kind of human – or even not human at all. An influential tradition of critical historians, from the Trinidadian C L R James to the historical geographer Jason W Moore, see the origins of racism and misogyny in all its modern forms in the new intellectual dispositions of capitalism, an economic system built around the enclosure of nature and its relentless exploitation for profit.

No human life since the 16th century has remained untouched by the processes this new divide in human thinking unleashed. Clearing the forests of Scandinavia and the Baltic, enclosing the common lands of Britain and Ireland, terraforming the mountains of Peru: all of these human activities, and many others besides, rapidly and dramatically changed Earth’s environment in a way that no prior human actions had done. Particularly in the Americas, the results were horrific. Millions of Indigenous people died of imported diseases, their land went fallow, and the trees that (re)grew on that fallow land sucked so much carbon out of the atmosphere that by 1610 global temperatures began to sink, only to begin rising again as the Industrial Revolution began emitting more carbon. That is why some scholars identify the years around 1600 as the beginning of the Anthropocene, the geological era in which human activity breaks into the geologic record. The echo of Tallis’s brilliant multifaceted music in gothic spaces – and its secret performance in the homes of Catholic dissidents – was as much the sound of this moment as Chimalpahin’s threatening, repetitive bells ringing out over the new Mexico City as it slowly drowned in the rain. A global history of music under the sign of the Anthropocene thinks the two together.