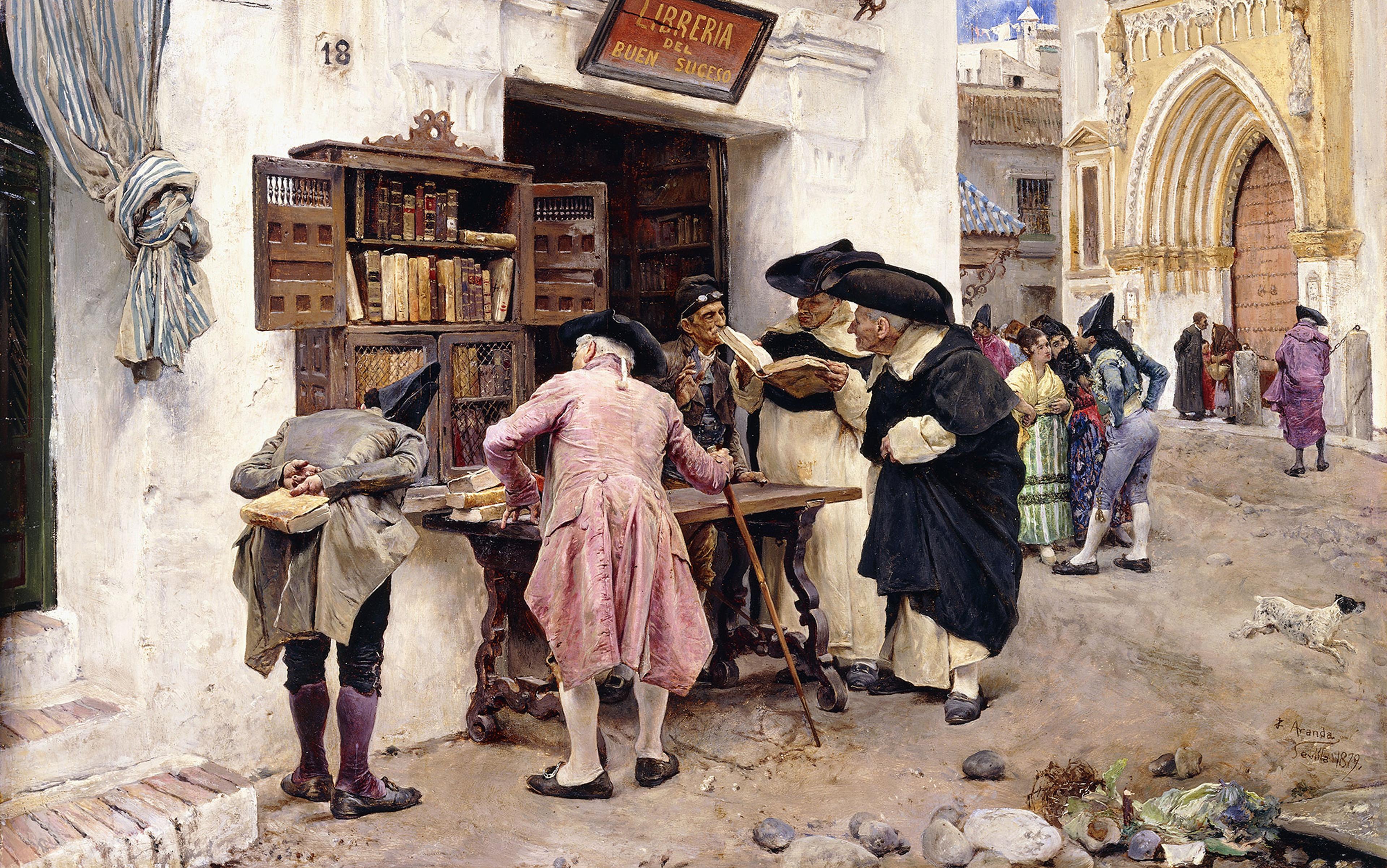

From 2009 to 2013, every book I read, I read on a screen. And then I stopped. You could call my four years of devout screen‑reading an experiment. I felt a duty – not to anyone or anything specifically, but more vaguely to the idea of ‘books’. I wanted to understand how their boundaries were changing and being affected by technology. Committing myself to the screen felt like the best way to do it.

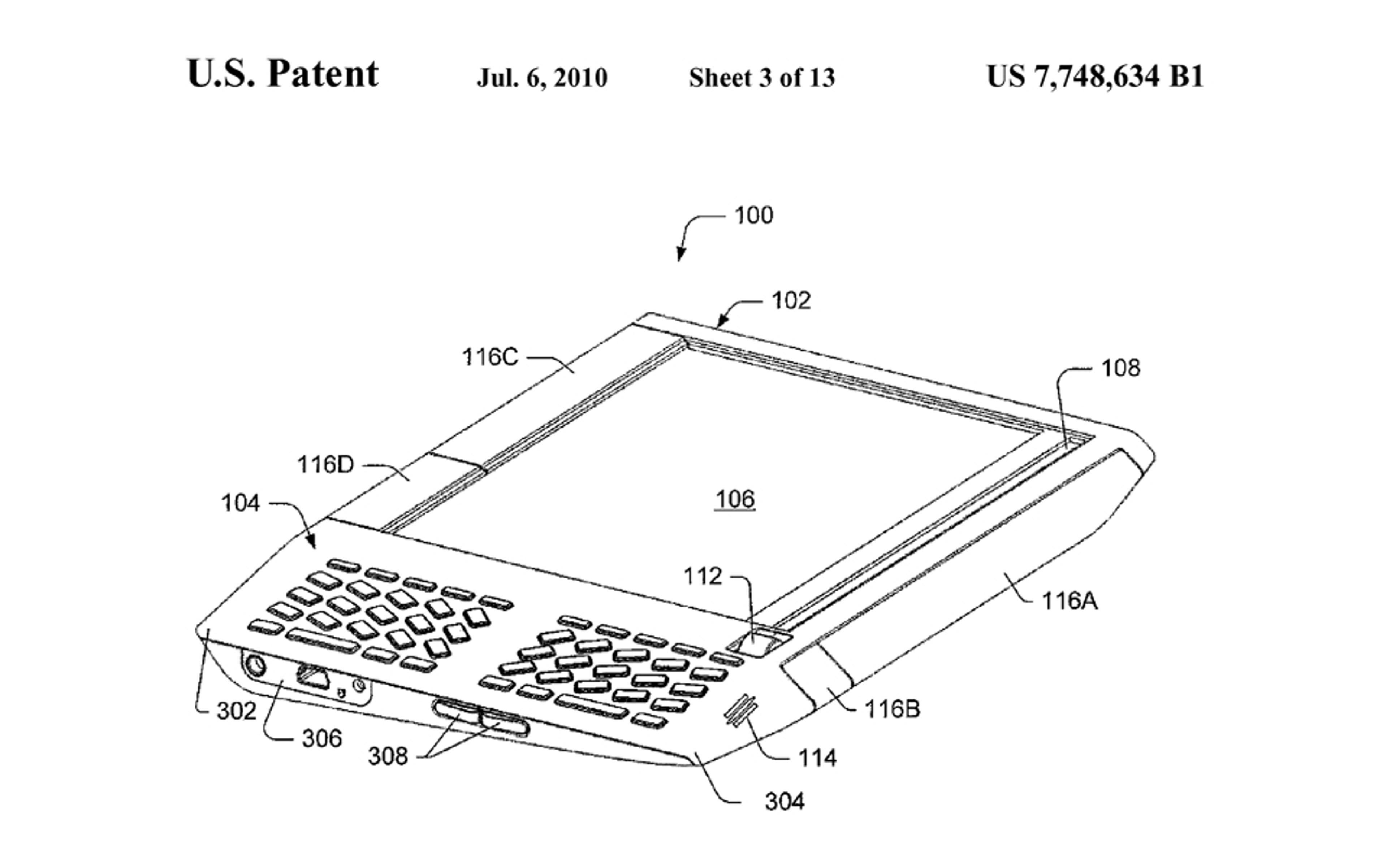

By 2009, it was impossible to ignore the Kindle. Released in 2007, its first version was a curiosity. It was unwieldy, with a split keyboard and an asymmetrical layout that favoured only the right hand. It was a strange and strangely compelling object. Its ad-hoc angles and bland beige colour conjured a 1960s sci-fi futurism. It looked exactly like its patent drawing. (Patent drawings are often abstractions of the final product.) It felt like it had arrived both by time machine and worm hole; not of our era but composed of our technology.

And it felt that way for good reason: you could trace elements of that first Kindle – its shape, design, philosophy – back 70 years. It evoked the Memex machine that the American inventor Vannevar Bush wrote about in ‘As We May Think’ (1945), a path-breaking essay for The Atlantic. It went some way toward vindicating Marshall McLuhan’s prediction that ‘all the books in the world can be put on a single desktop.’ It was a near‑direct copy of a device called the Dynabook that the early computer pioneer Alan Kay sketched and cardboard‑prototyped in 1968. It was a cultural descendant of the infinitely paged Book of Sand from a short story of the same name by Jorge Luis Borges published in 1975. And it was something of a free-standing version of the ideas of intertwingularity and hypertext that Ted Nelson first posited in 1974 and Tim Berners-Lee championed in the 1990s.

The Kindle was all of that and more. Neatly bundled up. I was in love.

The way we consume media changes over time. The largest changes can be explained, in part, through the lens of value proposition. For example: is the value proposition of reading a printed newspaper, with its physicality, its smell, its serendipity, its utility as a fly-swatter, greater than reading a newspaper’s website, which is immediate, universally accessible, networked, and sharable? Precipitous drops in print subscriptions indicate no. We readers see far greater value in the instant access and quick updates of the web than in the physicality of the printed broadsheet.

Granite, wood, wax, silk, paper, metal type, the Gutenberg press, Manutius’s octavo editions, Penguin paperbacks, desktop publishing software, digital type, on‑demand printing, .epub: the evolutionary path of ‘books’ has been punctuated by technological changes large and small. And so, too, with the Kindle.

Patent filed June 2006 for the Kindle Courtesy US Patent and Trademark Office

The Kindle set the imagination alight. It looked and felt like no ‘computer’ we had ever seen. And because its progenitor was paper – but yet it was digital – there was something magical in holding it. It was The Hitchhiker’s Guide made manifest. (A role that the iPhone would go on to fulfill in totality.) Unlike a desktop – at which we read straight-backed, vertically, some distance away from the text – we could cradle a Kindle. And because it was globally networked and backed by a vast and instantaneously available library, we rarely found it to be limited. That 2007 object held implicit the promise of a universal book container.

Previous attempts to make devices such as Kay’s Dynabook real – eg, Sony’s LIBRIé, released in 2004 – had been hampered by small libraries. Amazon’s library had no bounds, it had one-click purchasing. And, more generally, technology had improved: batteries were smaller, processors faster, e-ink displays higher-resolution. In the year of our lord, 2007, under the auspices of one company, all of the pieces came together making real those techno-prophecies of yore. Those of us of a certain codex geekery – myself included – were enthralled by its eccentricities and potential.

Containers matter. They shape stories and the experience of stories. Choose the right binding, cloth, trim size, texture of paper, margins and ink, and you will strengthen the bond between reader and text. Choose badly and the object becomes a wedge between reader and text.

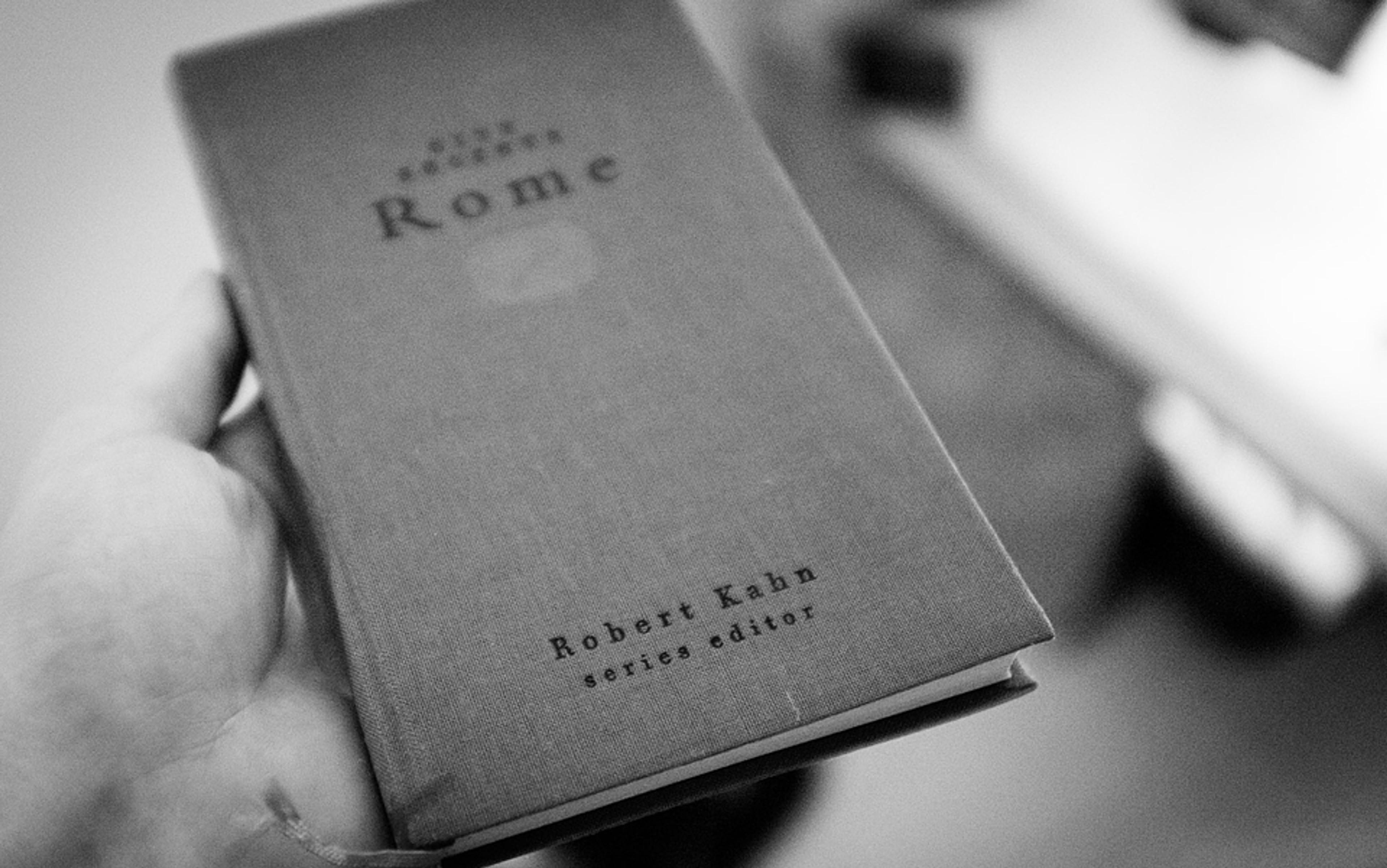

Photo by Craig Mod

Over the past 15 years, there have been two particular containers that have moved me. The first was a guidebook to Rome called City Secrets. I was 19 when I found it in my university bookshop. Bound in rust-coloured cloth, rough against the skin, with jet-black foil‑stamped lettering and a small key on the cover, City Secrets was skinny. The trim size was non‑standard, much taller than wide. It bent easily, fit handily into my jacket pocket, and was made with cover boards that had a reassuring springy resilience. The combination of the size and the cloth cover made it feel like a travel companion – a book that could take a beating, be dragged around the world, stored for years, and returned to, again and again.

I would read and take notes on the Kindle in bed, in a tent, on a train. It was an incredible user experience, delightful in its absurdity

I had seen older well-made books by the end of my teenage years – books such as the leather‑wrapped Overland Through Asia (1871), from the American Publishing Company in Hartford, found in the dusty stacks of a place called The Book Barn – but until City Secrets I had yet to come across a contemporary book as thoughtfully and deliberately made. Between its cover boards, the typography was elegant and readable. Its layouts functional. Its maps rendered with a perfect contrast. Despite having no means of visiting Rome, I bought it at once. Over the next decade, I’d go on to publish, write or design more than a dozen books, and City Secrets sat as my polestar. It affected the way I thought about every physical book I encountered.

The other container was, of course, the Kindle.

During my screen‑reading years, I found the Kindle to be most transformative in its ability to collapse the distance between wanting a book and owning it. When travelling, no matter how desolate the location, the older Kindle’s unlimited worldwide 3G – called Whispernet, and to the this day still one of the most innovative and forward‑thinking qualities of the Kindle platform – picked up enough of a signal to let me buy books when travel companions recommended them. Thanks to Amazon’s catalogue, the Kindle could deliver almost any book imaginable.

At night, I would read and take notes on the device in bed, in a tent, on a train. It was an incredible user experience, full of perceived value, delightful in its absurdity. Most importantly, using the device in these ways felt like an investment in the future of books and reading. Each Kindle book I bought was a vote with the wallet: yes – digital books! Every note I took, every underline I made was contributing to a vast lattice collection of reader knowledge that would someday manifest in ways beautiful or interesting or otherwise yet unknowable. This I believed. And implicit in this belief was a trust – a trust that Amazon would innovate, move the experience forward unpredictably, meaningfully, and delightfully. This belief – that Amazon was going to teach the old guard new tricks – kept me buying and reading and engaging.

New technologies are easily dismissible. And so an optimism and faith are critical to using emergent products. You must believe in what the thing might be moving toward, not what it is. This optimism and philosophy granted me special permission to overlook many of Kindle’s initial missteps – particularly in software design. I was critical of Kindle typography and layouts from day one, but I assumed that these errors would be remedied quickly. My book notes felt locked away in Amazon’s ecosystem, but I assumed they would eventually produce better interfaces or export options for more rigorous readers.

While the software wasn’t perfect, those four years did mark the pinnacle of Kindle hardware innovation. Each subsequent release was a significant improvement on the previous generation. Kindles became smaller, lighter, with higher resolution and more responsive backlit screens. The tactility of the page-turn buttons (the most – and arguably only – important buttons) improved. The battery lasted longer. And the device got cheaper. So cheap it inspired non-profits such as Worldreader to form and begin building digital libraries in Africa. It seemed that the Kindle hardware design team was honing in on the Platonic universal reading container.

If the pile of unread books on the bedside table is a graveyard of good intentions, the list of unread books on a Kindle is a black hole of fleeting intentions

But in the past two years, something unexpected happened: I lost the faith. Gradually at first and then undeniably, I stopped buying digital books. I realised this only a few months ago, when taking stock of my library, both digital and physical. Physical books – most of all, works of literary fiction – I continue to acquire voraciously. I split my time between New York and Tokyo, and know that with each New York trip I’ll pick up a dozen or more volumes from bookstores or friends. My favourite gifts, to give and to receive, are still physical books. The allure of the curated front tables at McNally Jackson or Three Lives and Company is too much to resist.

The great irony, of course, is that I’ve never read more digitally in my life. Each day, I spend hours reading on my iPhone – news articles, blog posts and essays. Short to mid-length content feels indigenous to the size, resolution and use cases of smartphones, and many online publications (such as this very site) display their content with beautiful typography and layouts that render consistently on any computer, tablet or smartphone. Phones also allow us to share articles with minimal effort. The easy romance between our smartphones and short-to-mid-length articles and video is part of the reason why venture capitalists have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into New York publishing upstarts such as Vox, Vice and Buzzfeed. The smartphone coupled with the open web creates a near-perfect container for distributing journalism at a grand scale.

But what of digital books? What accounts for my unconscious migration back to print?

Once bought by a reader, a book moves through a routine. It is read and underlined, dog-eared and scuffed and, most importantly, reread. To read a book once is to know it in passing. To read it over and over is to become confidants. The relationship between a reader and a book is measured not in hours or minutes but, ideally, in months and years.

As a consumer of digital books I feel delighted, but as a reader, I feel crestfallen. All of the consumption parts of the Kindle experience are pitch-perfect: a boundless catalogue, instant distribution, reasonable prices (perhaps once too reasonable, now less so with recently updated contracts). It’s easy to forget that Amazon doesn’t just frustrate publishers, it also powers a huge chunk of the internet – hosting files and providing servers for many of the largest companies in the world. That business alone accounts for nearly $2 billion of their bottom line. So it’s no surprise that Amazon has built seamless, efficient plumbing for digital books. But after a book has made its way through the plumbing and onto the devices, the once-fresh experience now feels neglected.

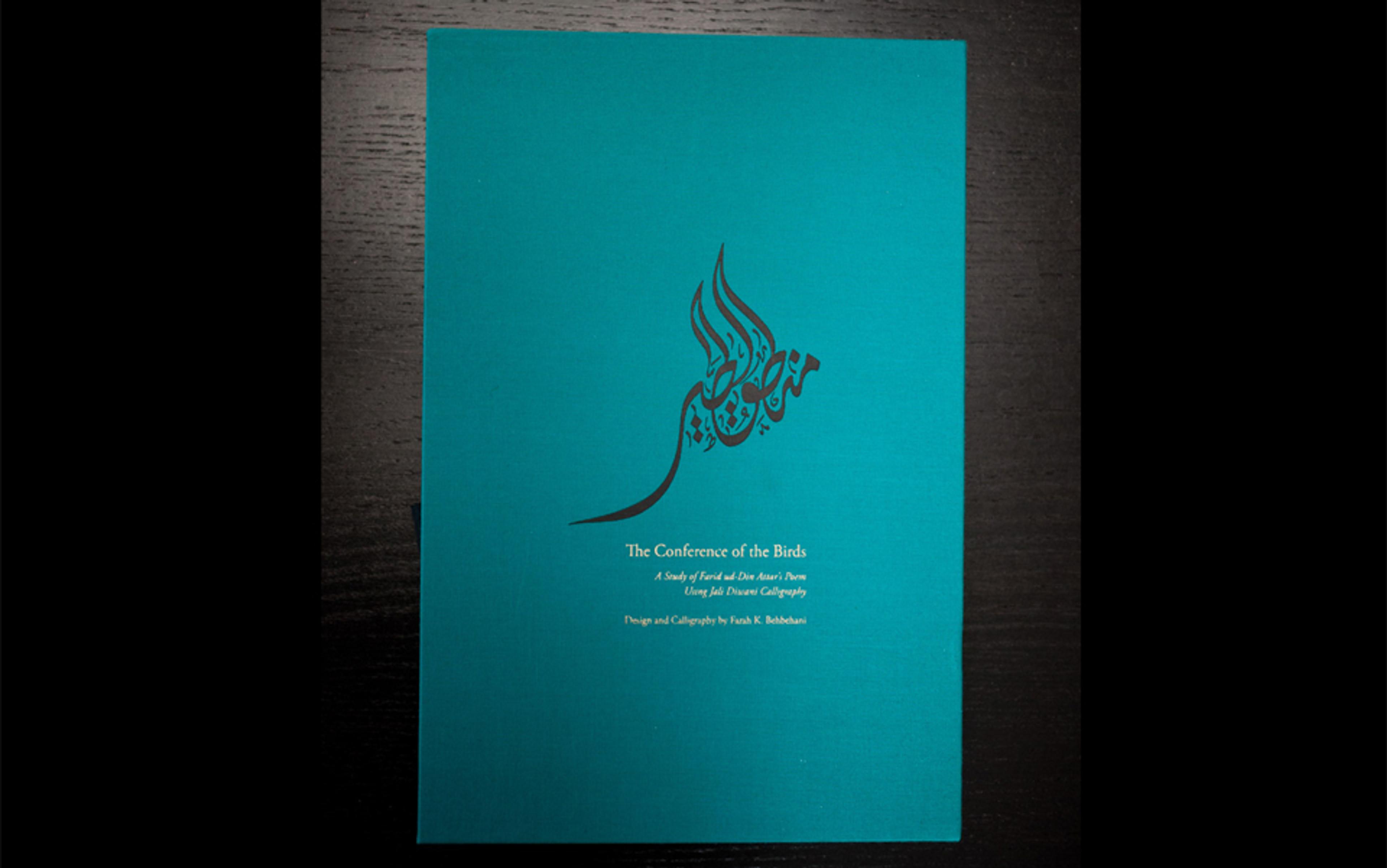

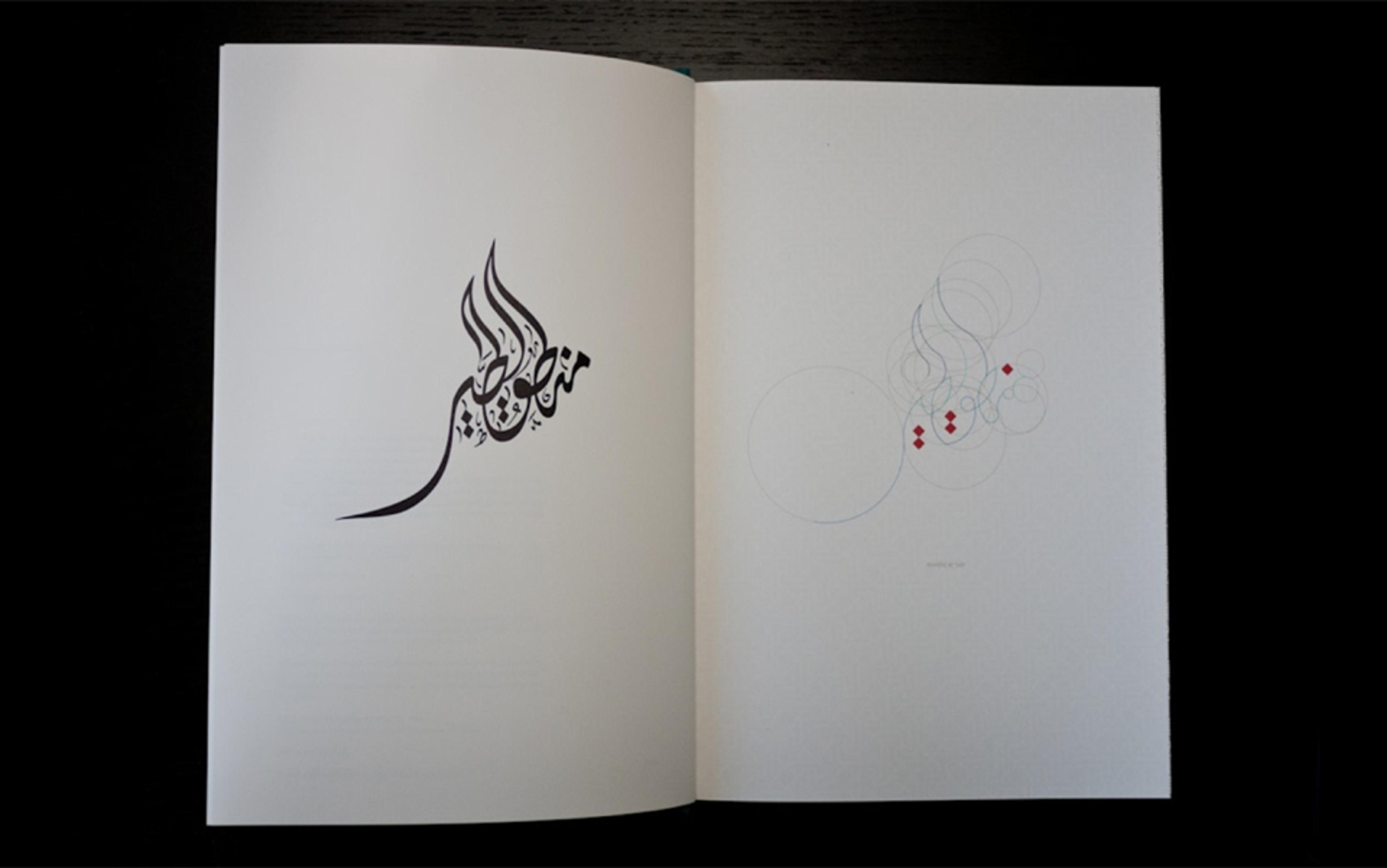

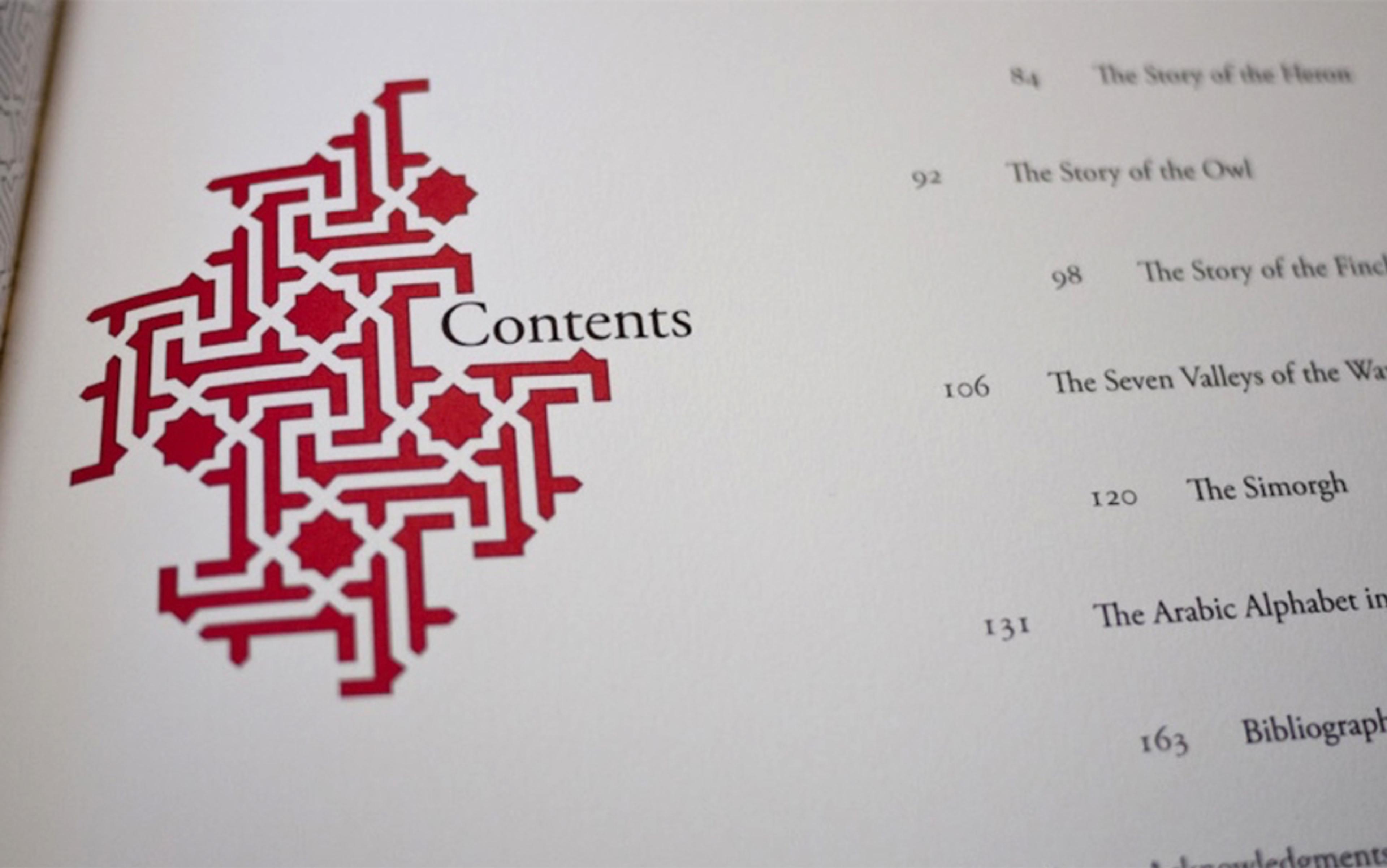

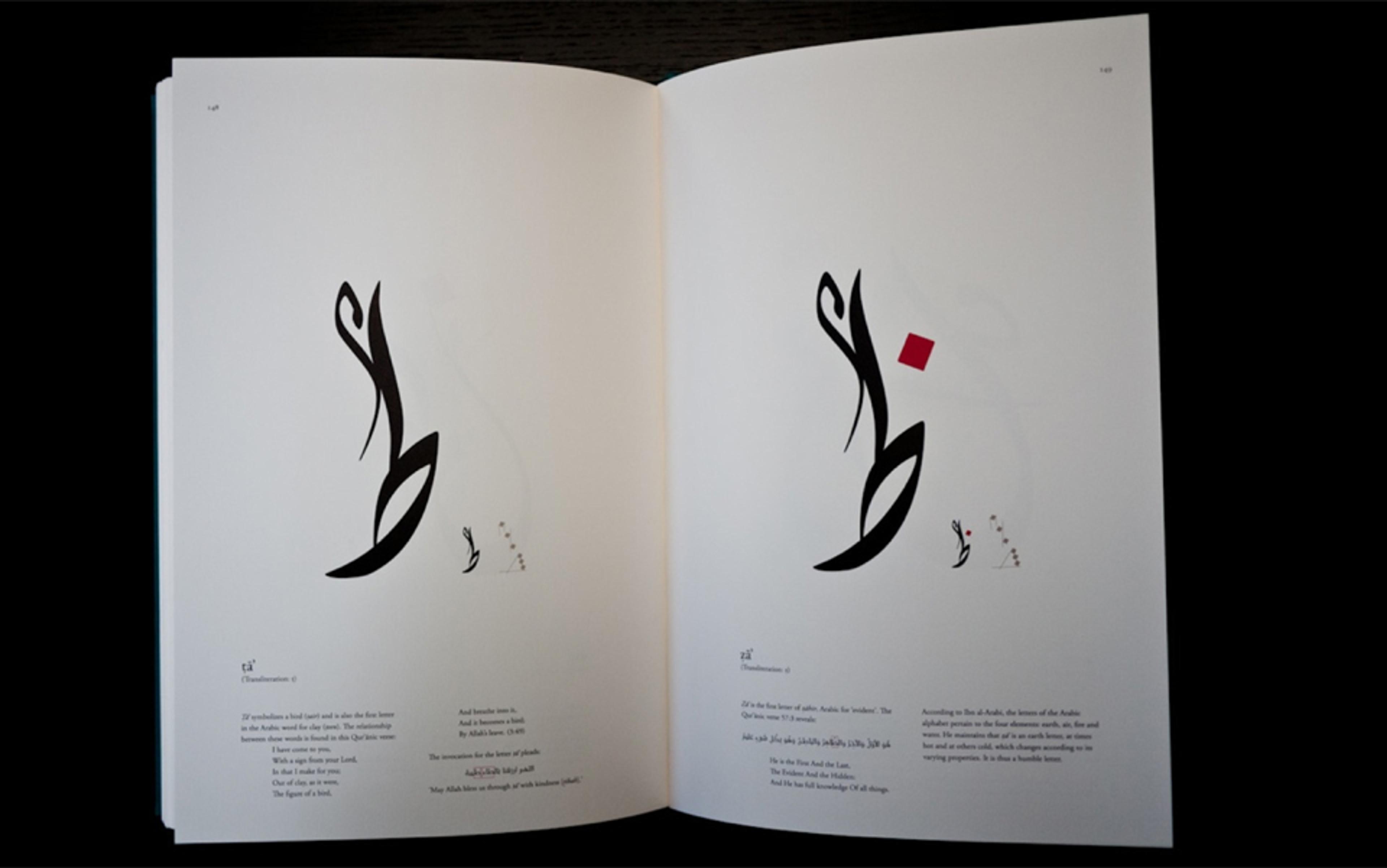

Take for example the multistep process of opening a well-made physical edition. The Conference of the Birds (2009), designed by Farah Behbehani and published by Thames and Hudson, is a masterclass in welcoming the reader into the text.

Photos by Craig Mod

Photos by Craig Mod

The object – a dense, felled tree, wrapped in royal blue cloth – requires two hands to hold. The inner volume swooshes from its slipcase. And then the thing opens like some blessed walking path into intricate endpages, heavystock half-titles, and multi-page die-cuts, shepherding you towards the table of contents. Behbehani utilitises all the qualities of print to create a procession. By the time you arrive at chapter one, you are entranced.

Contrast this with opening a Kindle book – there is no procession, and often no cover. You are sometimes thrown into the first chapter, sometimes into the middle of the front matter. Wherein every step of opening The Conference of the Birds fills one with delight – delight at what one is seeing and what one anticipates to come – opening a Kindle book frustrates. Often, you have to swipe or tap back a dozen pages to be sure you haven’t missed anything.

Because the Kindle ecosystem makes buying books one-click effortless, it can be easy to forget about your purchases. Unfortunately, Kindle’s interface makes it difficult to keep tabs on those expanding digital libraries: at best, we can see a dozen titles at a time, all as inscrutably small book covers. Titles that fall off the first-page listing on a Kindle cease to exist. Compare that with standing in front of a physical bookshelf: the eye takes in hundreds of spines or covers at once, all equally at arm’s length. I’ve found that it’s much more effortless to dip back into my physical library – for inspiration or reference – than my digital library. The books are there. They’re obvious. They welcome me back.

The pile of unread books we have on our bedside tables is often referred to as a graveyard of good intentions. The list of unread books on our Kindles is more of a black hole of fleeting intentions.

But it shouldn’t be a black hole, especially not after nearly a decade. Aside from revamping digital book covers and the library browsing interface, Kindles could remind us of past purchases – books either bought but left unread, or books we read passionately and should reread. And, in doing so, trump the unnetworked isolation of physical books. Thanks to our in-app reading statistics, Kindle knows when we can’t put a book down, when we plunge ourselves into an author’s world far too late into the night, on a weeknight, when the next day is most definitely not a holiday. Kindle knows when we are hypnotised, possessed, gluttonous; knows when we consume an entire feast of words in a single sitting. Knows that others haven’t been so ravenous with a particular story, but we were, and so Kindle can intuit our special relationship with the text. It certainly knows enough to meaningfully resurface books of that ilk. It could be as simple as an email. Kindle could help foster that act of returning, of rereading. It could bring a book back from the periphery of our working library into the core, ‘into the bloodstream’, as Susan Sontag put it. And yet it doesn’t.

To return to a book is to return not just to the text but also to a past self. We are embedded in our libraries. To reread is to remember who we once were, which can be equal parts scary and intoxicating. Other services such as Timehop offer ways to return to past photos or past tweets. They, too, are unexpectedly evocative. Far more so than you might think. They allow us to measure and remeasure ourselves. And if a resurfaced tweet has an emotional resonance of x, than a passage in a book by which you were once moved must resonate at 100x.

All is not well on the digital book design front. Until recently, the Kindle iOS application still lacked the ability – nearly five years after its launch – to hyphenate words at the end of lines in books as they appear on the screen; this was a small ‘problem’, but it’s one that should have been solved years ago. And that’s only one of many deeper usability and design issues. Amazon’s long-term neglect of the Kindle continues to be worrying to me, both as a designer and a reader.

It seems as though Amazon has been disincentivised to stake out bold explorations by effectively winning a monopoly (deservedly, in many ways) on the market. And worse still, the digital book ‘stack’ – the collection of technology upon which our digital book ecosystems are built – is mostly closed, keeping external innovators away.

To understand how the closed nature of digital book ecosystems hurts designers and readers, it’s useful to look at how the open nature of print ecosystems stimulates us. ‘Open’ means that publishers and designers are bound to no single option at most steps of the production process. Nobody owns any single piece of a ‘book’. For example, a basic physical book stack might include TextEdit for writing; InDesign for layout; OpenType for fonts; the printers; the paper‑makers; the distribution centres; and, finally, the bookstores that stock and sell the hardcopy books.

Thanks to desktop publishing software, print‑on‑demand, and even Amazon (for distribution), the production sequence of the physical book stack has become almost universally accessible. This represents one of the most significant shifts in publishing over the past 20 years. Today, any individual or independent publisher can create a physical book of almost any conceivable design and distribute it globally. This combination of accessibility and openness gives designers great latitude in typography, binding materials and papers. The playful design of books such as City Secrets or The Conference of the Birds is a direct result of this ecosystem. As a publisher, McSweeney’s has taken full advantage of this situation. They have pushed, pulled and stretched the boundaries of what a book could or should look like, how it should be packaged, how it should be read. And have done so because the raw material of the medium allowed them to do so.

We readers are the greatest beneficiaries of this open physical stack. When we buy a physical book, we can do with it what we want – cut up the pages, burn it for warmth, give it to friends, and so on. Because the contract of ownership between reader and object is implicit, not dependent on any third party, the physical book also becomes a true souvenir of the reading experience. One that can’t be revoked because of broken or neglected software. In effect, a longterm trust is embedded in the nature of a physical book.

Contemporary digital publishing stacks are mostly closed. As readers, when we buy an Amazon Kindle or Apple iBooks digital book, we have no control over what software we can use to read it, or what happens to our notes and other meta information culled from our reading data. Those notes I took in the tents while hiking back in 2009 still exist, somewhere, locked inside the Kindle ecosystem. I can dredge them up by going back in and raking through the books in question or pulling up the kindle.amazon.com website, which itself hasn’t had a significant update since it was launched six years ago. But they don’t exist, for example, as a simple text file, easily searchable, on any device or computer. Nor am I certain that they will continue to exist in coming years as Amazon changes the way its ecosystem functions.

Designers working within this closed ecosystem are, most critically, limited in typographic and layout options. Amazon and Apple are the paper‑makers, the typographers, the printers, the binders and the distributors: if they don’t make a style of paper you like, too bad. The boundaries of digital book design are beholden to their whim.

The potential power of digital is that it can take the ponderous and isolated nature of physical things and make them light and movable. Physical things are difficult to copy at scale, while digital things in open environments can replicate effortlessly. Physical is largely immutable, digital can be malleable. Physical is isolated, digital is networked. This is where digital rights management (DRM) – a closed, proprietary layer of many digital reading stacks – hurts books most and undermines almost all that latent value proposition in digital. It artificially imposes the heaviness and isolation of physical books on their digital counterparts, which should be loose, networked objects. DRM constraints over our rights as readers make it feel like we’re renting our digital books, not owning them.

The books I’ve returned to again and again, and that have followed me throughout my life, cover my walls. I have been reading Sandra Cisneros’s House on Mango Street (1991) for nearly two decades. It never ceases to remind me what writing honestly and simply about one’s childhood looks or feels like. All these years later, Paula Fox’s The Coldest Winter (2005) still moves me to travel harder and more boldly. Physical books are raw souvenirs, totems pulled through space and time, laden with emotional value, products of an open relationship between the reader and the object.

As our hardware has grown more powerful and our screens more capable, our book-reading software has largely stagnated

Many of these digital concerns would be rendered moot with more open digital-reading ecosystems. Without proprietary DRM, we could copy and back‑up our books with ease. Even if Amazon stopped supporting Kindle (as Sony did with LIBRIé, as Yahoo! did with Geocities, and as countless other huge corporations have with their seemingly invincible products and communities), we could be certain that our books and reading data would still be accessible. With a proper API (an application programming interface, which allows one authorised application to read and manipulate data in another), entrepreneurs outside of Amazon or Apple could step in and offer more beautiful, efficient, or innovative reading containers for our books, leaving the bigger companies to do what they do best: payments and infrastructure.

Individually, these niggles might seem small and inconsequential, but over time they gnaw, erode trust, and perhaps inspire one to move back to print. Back to an ecosystem that’s old but fully formed, chock-full of reliability and delight. In contrast, our digital book ecosystems feel stillborn. Certainly not like the same fresh, potent universes they did five or six years ago when the Kindle was nascent and the iPad had just been announced. As our hardware has grown more powerful and our screens more capable, our book-reading software has largely stagnated. Many of the typographic and user experience gripes I had during my four years of peak Kindle usage remain to this day.

In other words, digital books and the ecosystem in which they live are software, and software feels most alive and trustworthy when it is actively evolving with the best interests of users in mind. An open stack is not strictly necessary for this, but it certainly helps.

In early August I visited Bret Victor’s Communications Design Group research laboratory in San Francisco. Against the far wall of the lab’s library stood a 10-foot wooden bookshelf. It was stuffed with manuals on the history of computers and programming and interfaces, novels and countless non-fiction books.

From behind me, Bret said: ‘Watch this,’ and pointed a small green laser at one of the books. The spine – the physical spine – lit up and above the bookshelf the book itself exploded onto an empty swath of wall. The entirety of its contents, laid out page by page by some hidden projector. The laser tracked by some hidden constellation of cameras. In his hand, Bret held an iPad, and as he pointed the laser at various projected pages they appeared on his device. As he slid from page to page on the iPad, the corresponding pages on the wall enlarged. It was a way to view both the macro and micro of a book – the overarching structure of the whole and the minutiae of the paragraph. The margins, it must be said, were gorgeous.

The next step, Bret said, was to get all of the books properly scanned and indexed. Soon enough, you’d be able to type in any search term, and the related physical volumes would glow, their collected relevant pages appearing above. But this was possible only by performing your own scans, owning your own data, placing it in an open, malleable format. A supple data source, it seemed, was the only way to hold forth these investigations.

Bret’s magic bookshelf reminded me of a quote by Alan Kay. Explaining his Dynabook concept to a group of children in 1968, he said: ‘I want to be able to do all the things you can do with a book, but be dynamic.’ There was something about the playful quality of the magic bookshelf that felt like it had achieved spiritual lockstep with Kay’s goals. The bridging of the digital and physical seemed oddly and unexpectedly fresh, prescient, like a rich vein worthy of continued mining.

Seeing that bookshelf was the first time I had been delighted by digital books in years, and it was a stark reminder that pliancy of media invites experimentation. When media is too locked down, too rigid, when it’s too much like a room with most of the air sucked out of it, stale and exhausting, the exploration stops. And for the intersection of books and digital there’s still much exploration to be had.

Where will those explorations happen? I don’t know. But I do know that print has endured and continues to endure for good reason. Our relationships to our most meaningful books are long and textured. And until we can trust our digital reading platforms, until the value propositions of digital are made clearer, until the notes and data we produce within them is more accessible and malleable, physical books will remain at the core of our working libraries for a long time coming.

Have I ever been to Rome? Not yet. But when I do go, my walks will be guided in equal parts by Google Maps and a tiny clothbound book.