The novelist Elias Canetti liked to say: ‘I try to imagine someone saying to Shakespeare: “Relax!”’ – and Susan Sontag liked to cite him saying it. I, in turn, like to cite Sontag citing him, because I like to place myself in this lineage of people who work too hard and take things too seriously.

When I first read Against Interpretation and Other Essays (1966) in grad school, I fell in love with Sontag’s defiant excess and excessive seriousness – the very things that make her work endlessly relevant, and endlessly urgent. Love is not too strong a word for the fascination I have held for her, the mystery of transubstantiation at work that could lead her to take up familiar cultural touchstones – Jean-Luc Godard, Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, happenings, photographs, the critical project itself – and transform them into dazzling, death-defying essays. I took her as my own personal hero, to emulate in all things. With the bravado of youth I’d no doubt that if I worked really hard, and read everything, eventually I would reach her level of brilliance and erudition.

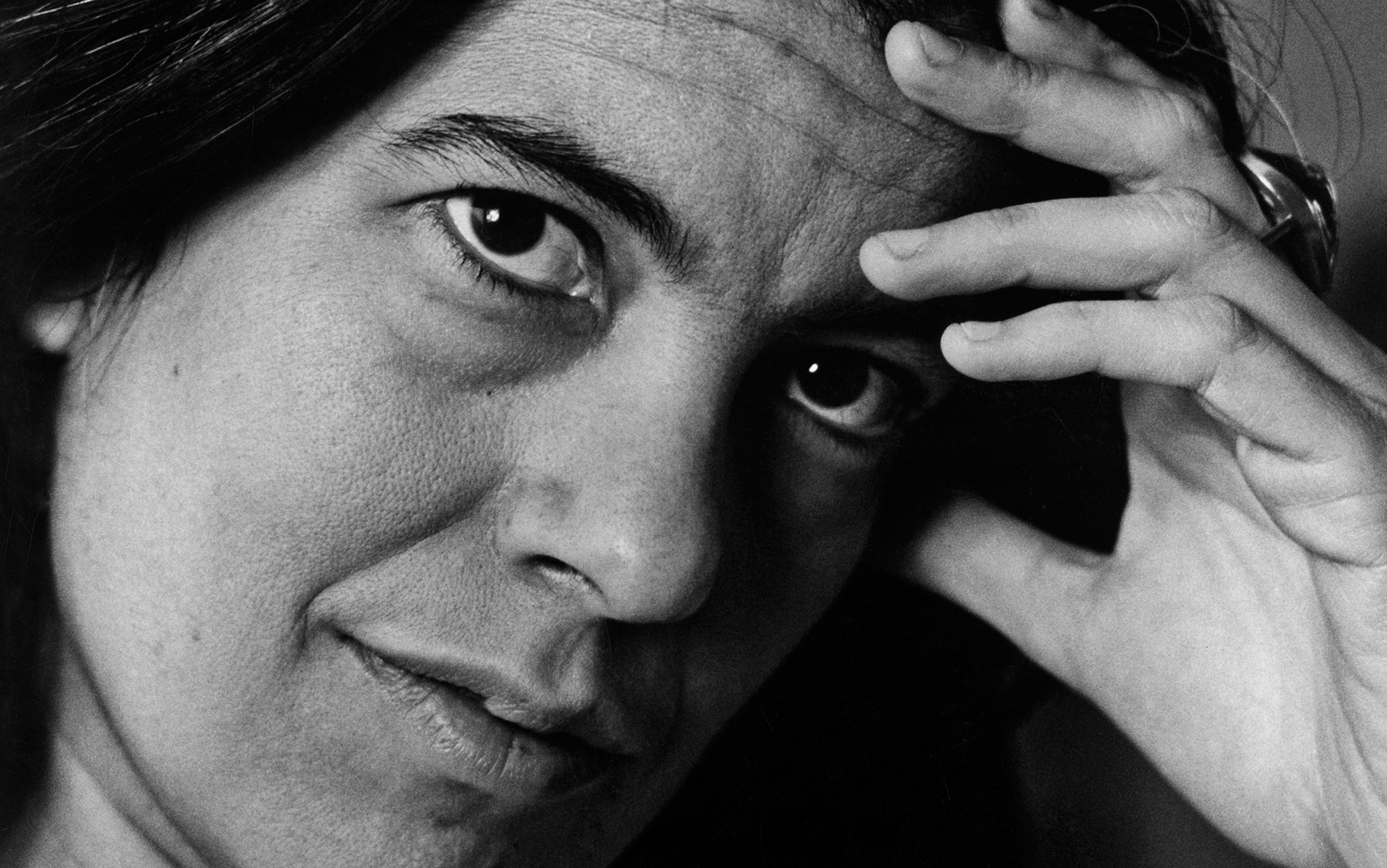

Sontag had no time for the kind of faux humility that women are conditioned to perform anytime anyone shows interest in what we do. She gave no fucks, in the lingo of the internet, a particular patois she did not live to see. She became famous as a critic and essayist by being publicly serious about all kinds of culture, low to high; for elevating ‘camp’ to an aesthetic theory; for calling for an ‘erotics of art’ to replace the systematic forms of interpretation she perceived as stand-ins for engaged critique: symbology, exegesis, Marxism, Freudian psychoanalysis. But she remained famous because her continued scrutiny of art, as well as her work on photography, illness and torture, was so perceptive, even morally compelling, that it gave us the primary terms in which we understand these phenomena in a cultural context.

Born in New York in 1933, but raised in Tucson, Arizona and southern California, Sontag felt keenly, in her formative years, that she was different from other people, especially her family. She would later say that she grew up surrounded by philistines; she called it a ‘prison sentence’, casting herself in the defiant role of jail-breaker. When she left for university at Berkeley at 16, she built herself up from that bookish girl from the Southwest, using her diaries as scorecards for what she read, or wanted to read, and for developing her ideas about the self, art and sexuality. Lists, lists, so many lists, and admonishments, and hopes, fill their pages. ‘The self is a project, something to be built,’ she wrote in an essay on Benjamin.

After an ill-fated marriage to the scholar Philip Rieff, with whom she had a son, she moved abroad to Oxford then Paris, before settling in New York. There, she discovered a world of people who read Hegel, went to the theatre and wrote for the Partisan Review, things that had been so out of reach to the adolescent Sontag that she lunged for them with all the more force. She brought her hunger for experience, knowledge, conversation, connection and inspiration to bear across disciplines, writing novels, essays, stories, plays and films that never lost their connection to politics and activism; she was an écrivain engagée in the purest form, travelling to Hanoi during the Vietnam War, presiding over American PEN, writing tirelessly about torture and war, and responsibility.

In Sarajevo in 1993, during the Bosnian war, she staged a production of Waiting for Godot (1953): it seemed to Sontag as if it had been written ‘for, and about, Sarajevo’. As she told the American TV journalist Charlie Rose in 1995: ‘Waiting for the American intervention. I mean, it was like waiting for Godot.’ The production drew scathing responses in the US and the UK: it was called ‘mesmerisingly precious and hideously self-indulgent’. It was not, Sontag countered, ‘redundant’ or ‘pretentious’ to stage a play about despair in a place where people were in despair, and where it might offer them a way to feel ‘strengthened and consoled by having their sense of reality affirmed and transfigured by art’. It is almost incredible to look back and see how angry a theatre production could make people when Sontag was at the helm.

With her debut essay collection in 1966, Sontag became a star in a way we can’t really conceive of today; and when her earlier essay ‘Notes on “Camp”’ (1964) was picked up by Time magazine, she was practically a household name. I’m trying to imagine an essay in n+1 having that kind of crossover power today; the closest thing I can think of is Rebecca Solnit’s essay on mansplaining (first published on TomDispatch.com in 2008) which, though it has certainly won Solnit new audiences, has not made her a celebrity of Sontag’s order.

Sontag maintained her fame (inadvertently, she always claimed) by courting controversy, as when, writing about the Vietnam War, she called the white race the ‘cancer’ of humanity (later she took this back, writing against the use of cancer as metaphor); or when, writing in The New Yorker on 24 September 2001, she said that 9/11 ‘was not a “cowardly” attack on “civilisation” or “liberty” or “humanity” or “the free world” but an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed superpower, undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions’.

We need monsters like Sontag because they aren’t afraid to speak a certain kind of truth

There were accusations of unfeeling monstrosity, and even a few death threats. ‘I was a lightning rod,’ Sontag commented in a later interview. ‘I wasn’t the only voice in America to say things like this.’ But on some level, she knew she’d be ‘drawn and quartered’ in the media as long as she persisted in pointing out unpopular truths. As Rafia Zakaria wrote in 2017, Sontag was ‘adept … at carving out a position of dissent and non-complicity against even the most intractable milieu’. But it would have been unthinkable for Sontag not to speak her mind, no matter how unpopular it made her – and ‘speaking her mind’ meant articulating a nuanced, often contrarian position. She was an enemy of the pieties that people seemed to want from writers, then as now. There would always be plenty of other people happy to provide them. Why should she voluntarily blend into the din?

This is how I see her monstrosity: residing not in whether she was or was not likeable, but in her relentlessness, and her refusal to pander. The word ‘monster’ comes from the Latin monere, to warn. We need monsters like Sontag because they aren’t afraid to speak a certain kind of truth: cutting through cant, received opinion, nationalist rote, the efforts of alt-Right bot farms. We need critics who insist on hierarchies of thought and output, instead of buying into marketing hype that makes everyone really, really good, critics who don’t lunge straight for content, for what a book is ‘about’ or what it ‘says’, but who stop to consider form, and style – which, as Sontag shows us, are inextricably bound up in content. We need critics to keep us on our toes, to question authority, sweeping claims, totalising world views. We need Sontag to help us think for ourselves, and be unafraid to speak our minds. And we need her for these things now, more than ever. Maintaining a lively critical capability isn’t just about snark. It’s how we’re going to make it out of these dark days of nationalism and populism with our democracy intact.

There are things it has taken me two decades as a serious reader and writer to become aware of or to articulate, things that Sontag noticed straight off the bat in Against Interpretation, at the age of 33. Skimming her essays today, I’m struck by the sharpness of their insights and the breadth of their references. Dismayingly, nearly 20 years after I first read her, I still have not caught up to Sontag, and neither has our critical culture.

You won’t find Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Hume or György Lukács nonchalantly dotting the page in criticism today; it is supposed that readers aren’t up for it. But Sontag charges in and dares to distinguish between their good and mediocre work. She isn’t afraid of Jean-Paul Sartre. Writing on his book on Jean Genet, she notes: ‘In Genet, Sartre has found his ideal subject. To be sure, he has drowned in him.’ She stood up to men held up as moral giants. Albert Camus, George Orwell, James Baldwin? Excellent essayists, but overrated as novelists. In 1966, Sontag checked an America that was in thrall to realism and normative morality, demonstrating how to respond to the ‘seers, spiritual adventurers, and social pariahs’ as she put it in her essay on the French dramatist Antonin Artaud.

Her special brand of monstrous relentlessness saw her go in search of paradox. Moderation, and those who practised it, never interested her. It seemed to her like a cop-out. And she believed that only the immoderate rose to the level of the culture-hero: people who took things to extremes, who were ‘repetitive, obsessive, and impolite, who impress by force’, as she wrote of the French philosopher Simone Weil. Sane writers are the least interesting writers, and Sontag had that stripe of insanity, like that grey thatch of hair, that made you sit up and listen, and also made you a little nervous. Her pungent public personality won her a reputation for being, as Sigrid Nunez put it in 2011, ‘a monster of arrogance and inconsideration’. She was a monster – for art. She read everything, watched everything, listened to everything, went to see everything. How did she fit it all in? It’s as if she lived several lives in one. She sat in the middle of the third row at the cinema, so that the image would overwhelm her. She would not, could not, relax. Art was too important. Life was too important.

Look across her many books: she simply does not let up. Every sentence is a new challenge; there is no filler. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve read On Photography (1977), and every time it’s like I’m reading a new book. There’s something very constructed and Germanic about her sentences; I find myself reading her cubistly, not left to right only but also up and down, piecing together what she’s saying chunk by chunk instead of line by line. She quotes very infrequently, and is less interested in local textual moments than in building up a global reading of an author’s work. She frequently revised her opinions, so no sooner have I got a handle on On Photography than she’s off on another tack in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), further refining it in ‘Photography: a Little Summa’ (2003). She was uninterested in boiling down her views to an easily citable argument; she resisted simplification in every aspect of her life and work.

She wasn’t just serious: she was passionate about the mind and its possibilities

‘Boring, like servile, was one of her favourite words,’ writes Nunez in Sempre Susan (2011), recalling her time as Sontag’s assistant and her son David’s girlfriend. ‘Another was exemplary. Also, serious.’ The word ‘serious’ and its variants (‘seriousness’, ‘seriously’) appear 120 times in Against Interpretation, a text of 322 pages. That’s every 2.6 pages. For Sontag, seriousness was an all-encompassing, even physical way of being in the world. ‘Yet so far as we love seriousness, as well as life, we are moved by it, nourished by it,’ she wrote in her essay on Weil. ‘In the respect we pay to such lives, we acknowledge the presence of mystery in the world – and mystery is just what the secure possession of the truth, an objective truth, denies.’ Mystery is missing from all that is sage, appropriate, nice, fitting, obedient. Notice Sontag’s emotive, personal choice of words: we are moved by seriousness; it affects her (and, she presumes, her reader) on a primary, physical level.

This is what her detractors so often miss in her work. ‘Mind as Passion’ she called her essay on Canetti. Style. Will. Mind. Passion. These are also words that recur throughout her work. She wasn’t just serious: she was passionate about the mind and its possibilities. The mind, to Sontag, was a feeling organ. What she said of Barthes could easily be said of herself – perhaps she wished us to think it of her?

It was not a question of knowledge (he [Barthes] couldn’t have known much about some of the subjects he wrote about) but of alertness, a fastidious transcription of what could be thought about something, once it swam into the stream of attention. There was always some fine net of classification into which the phenomenon could be tipped.

Alertness and sensitivity were for Sontag ways of knowing as well as feeling; reading and learning and writing were physical states. Against interpretation, an erotics. Never one without the other. Towards the end of her manifesto ‘Against Interpretation’, which opens that collection, she urges the reader to ‘recover’ her senses. ‘We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.’ More, more, more. It is galvanising to encounter this kind of commitment, especially as a woman, raised to be just so, appropriate, kind and generous.

The commitment Sontag had to her work is often confused with self-seriousness. She certainly didn’t help matters: she could be unpleasant, dismissive and condescending, and didn’t try to be otherwise. Good for her. Heroine. Her personal idiosyncrasies have been explored in a range of memoirs, from Phillip Lopate’s book Notes on Sontag (2009) to Terry Castle’s essay ‘Desperately Seeking Susan’ (2005) to Sempre Susan (she was the kind of person who inspired memoirs in those who knew her). A collection of scholarly critical articles about her work is entitled The Scandal of Susan Sontag (2009). I have imprinted on my mind the image of her railing against the young Maureen Freely for not being able to parallel park. (As if anyone could, with Sontag in the car.) Frequently she’s accused of having no sense of humour. The playfulness of an essay such as ‘Notes on “Camp”’ seems to have passed many people by. It’s like she’s joking in another key.

It’s true that in interviews she can come across badly, because of the precision with which she thinks, but also the literalism, and the bossy defensiveness with which she approaches her way of thinking. In a TV interview with Chris Lydon in 1992, she lays into him for asking ‘journalistic’ questions about her thoughts on ‘pop culture’, refusing to entertain the idea of a split between high and low art: ‘I’m not a pundit,’ she insists, twice. It is difficult to watch. You cringe on her behalf; she is so defensive, so out of order. But also: fascinating. On video, you can see from the unwavering way she watches the people interviewing her that she can barely withstand being exposed to (what she clearly perceives as) their idiocy, but she has chosen to be there for whatever reason (shoring up her fame? Her bank account?) so she has to grit her teeth and answer their questions. There is an honesty in her inability to play the self-promotion game, and do it with a smile, that I admire almost as much as her work. Yet her very integrity made her a catch-all target for anti-intellectual jibes.

For a product of the American Southwest, she was astonishingly European in her worldview. Then again, perhaps no one is as European as an alienated American. There is something in our tradition that makes people suspicious of intellectuals, especially Continentals. This might account for why Sontag was so drawn to German philosophers, French writers and filmmakers, the nouveau roman, and also why the mainstream media never gave up its fascination with Sontag, even as it persisted in misunderstanding her, making her a star and keeping its lens trained on her, but framing her in ways that she refused to recognise.

The suspicion was mutual. ‘There is a terrible, mean American resentment toward a writer who tries to do many things,’ she wrote in 1972, on the death of the author Paul Goodman. At one point in Against Interpretation she calls out American and British critics for their ‘cozy’ taste in the novel, which she calls ‘philosophically naive’ for the way that it clings to the 19th-century novel and the ‘prestige of “realism”’. She confronts them with the ‘serious’ contemporary work being produced in France by writers such as Nathalie Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet or Michel Butor, books generally classed under the term nouveau roman, striking for their lack of plot, or character, or psychological analysis. ‘I no longer trust novels which fully satisfy my passion to understand,’ she declares. It is a sentiment that Anglo-American literary criticism seems finally to have caught up with, at least in its embrace of writers such as Sheila Heti and Rachel Cusk, both of whom have made provocative public statements about their ennui with conventional novelistic form, the pointlessness of making up characters and putting them through the motions of a plot. ‘It is harder for a woman,’ Sontag admitted to Nunez. ‘Meaning: to be serious, to take herself seriously, to get others to take her seriously.’ Is this why she was so studiously anti-autobiographical in her own interpretive work?

The paradoxical result of some of the French theory that Sontag helped to popularise in the US – the kind of poststructuralist philosophy that questioned grand narratives and Enlightenment values as tools of the patriarchy – is that the Right-wing ideologues with a stranglehold over American and British politics now use interpretation as a weapon. It’s just my opinion, they claim and, on the Left, we find ourselves in the novel position of having to defend ‘the truth’ as it has been captured on film or in print; there are some things that are not a matter of opinion, but a matter of record. Journalists such as Matthew d’Ancona or Michiko Kakutani have (with no small amount of glee) accused the ‘relativists’ of going too far, of giving us Donald Trump and Nigel Farage. Even philosophers such as Bruno Latour, back in 2004, fretted that postmodern thought had perhaps gone too far, when the warnings about climate change are dismissed as scientific ‘opinion’ instead of verifiable reality.

‘In some cultural contexts, interpretation is a liberating act. It is a means of revising … the dead past’

The supposedly democratic space of social media is the principal sphere in which proliferating personal opinions are given proper platforms as if they were matters of record, not of ideology or spin. In ‘Notes on “Camp”’, Sontag refuses the ‘familiar split-level construction’ as an example of too-easy, journalistic thinking. She is anti-dialectical: her thinking does not begin, or end, with an either/or proposition, of the kind that social media encourages in bite-sized Tweets, soundbites and false equivalencies. How devastating that Sontag died before the existence of Twitter; I’d have loved to read her critique of it. It would have been eviscerating. She, herself, would not Tweet; she would be endlessly cross with our hot takes and undigested opinions, our virtue-signalling and dog-whistling. It is the opposite of thought, the opposite of seriousness. How, too, might she have coped with the information overload of our day? Would she get less work done, falling down the click-hole of YouTube, finding different productions of her favourite plays or operas, clips of her favourite films, all available at her fingertips?

Throughout Against Interpretation, Sontag insisted on the importance of historical specificity, which is not the same thing as relativism. The same intellectual moves will take on different values at different times; our very way of encountering art, politics and ethics shifts with time and place, and is inflected by that perspective. The way that we ask and answer questions is a gesture at understanding that is itself situated. Our interrogations do not have the same motivations or yield the same truths. She writes: ‘In some cultural contexts, interpretation is a liberating act. It is a means of revising, of transvaluing, of escaping the dead past. In other cultural contexts, it is reactionary, impertinent, cowardly, stifling.’ It was important in the years following Against Interpretation and Jacques Derrida’s De la grammatologie (1967) – the years of the Vietnam War, when, as Sontag details in her various writings on photography, images of war were being disseminated by TV crews as well as by photographers – to ask how ideas were constructed, in what contexts, under whose authority. And it is important in our own time to refer to statements made on camera, or yes, on Twitter, in the face of politicians who deny the reality of their own public records.

In her essay ‘On Style’, she expands further. Our situatedness in history directly correlates with the way that we perceive anything – art, power, fact, opinion – at a given moment:

It is not only that styles belong to a time and a place; and that our perception of the style of a given work of art is always charged with an awareness of the work’s historicity, its place in a chronology … [But] the visibility of styles is itself a product of historical consciousness. Were it not for departures from, or experimentation with, previous artistic norms which are known to us, we could never recognise the profile of a new style.

For Sontag, style itself is historically produced, not innate. Ethics, similarly, are something you practise, not something you inherently have: ethics as style, perceived through our particular historical consciousness. This strikes me as one of the most important observations in Against Interpretation: what we are sensitive to is a function of where we’ve been and what we have to compare it with. This has implications beyond art. We have to keep asserting that the current ethics of governing is unacceptable. We cannot normalise it and assimilate it into our idea of what governing is. We have to regard it as an anomaly that we will not tolerate.

Sontag’s own style was monstrous; inspiringly monstrous. We’re used to hearing this term ‘monster’ as an insult. But the monster – a figure of excess, difficult to absorb culturally – confronts us with the limits of our own powers, and forces us to rise to the level of what the text, or the time, demands from us. ‘It is not important whether or not Sontag was always right in her conclusions, only that she was right in raising the issues that she did,’ wrote Solnit in her tribute to Sontag in 2005, ‘for the most useful position is the one that prompts people to test an idea and perhaps think for themselves by disagreeing.’ There is something missing in the public discourse because Sontag is no longer a part of it. We need to fill the void by continuing to read her and think through her ideas, even and especially where we disagree with them.