Picture yourself in a supermarket aisle in 2050. These new ‘magic meatballs’, brightly coloured for the kids, seem worth a try. Better have some of the meat powder too, one of the more established products from the mass-manufacturers of cultured meat – you can make that creamy meat-based fondue that always satisfies. You don’t fancy the meat ice-cream today, but there’s still time left for a trip to the deli counter, for some expensive, but delicious ‘rustic’ meat, matured in special vats, or perhaps some knitted steaks. And you can pile your cart secure in the knowledge that no animals were harmed in the making of any of these offerings.

At the moment, in vitro meat is a laboratory venture, yielding expensive and unappetising-looking muscle fibres that might be fit for filler in pies or burgers. But suppose the researchers’ ambitions are realised? Where will the technology go? How will it be marketed and consumed? Who might want it, and what for? These questions animate The In Vitro Meat Cook Book (2014) by Koert van Mensvoort and Hendrik-Jan Grievink, whose recipes for hypothetical products are sampled above. The authors’ open-ended, imaginative approach makes the book a good example of a new way of questioning technology: design fiction. As questions about technological choices trouble us more and more, it could be that design fiction, not science, has the better answers.

The stories we tell ourselves about technology – typically, optimistic ones from would-be innovators, pessimistic ones from their critics – are usually too simple. Making them more complex can support a richer discussion about where a technology might be going, and the kind of futures it could open up. That calls for a kind of realism in the depiction of technical possibilities that is inspiring a new cadre of practitioners of design fiction, or critical design. In the cookbook, for example, that realism comes from using a familiar recipe format to take the reader into unfamiliar worlds. The future facts are imagined, but not fanciful in the context of current research. They might never happen, but they could.

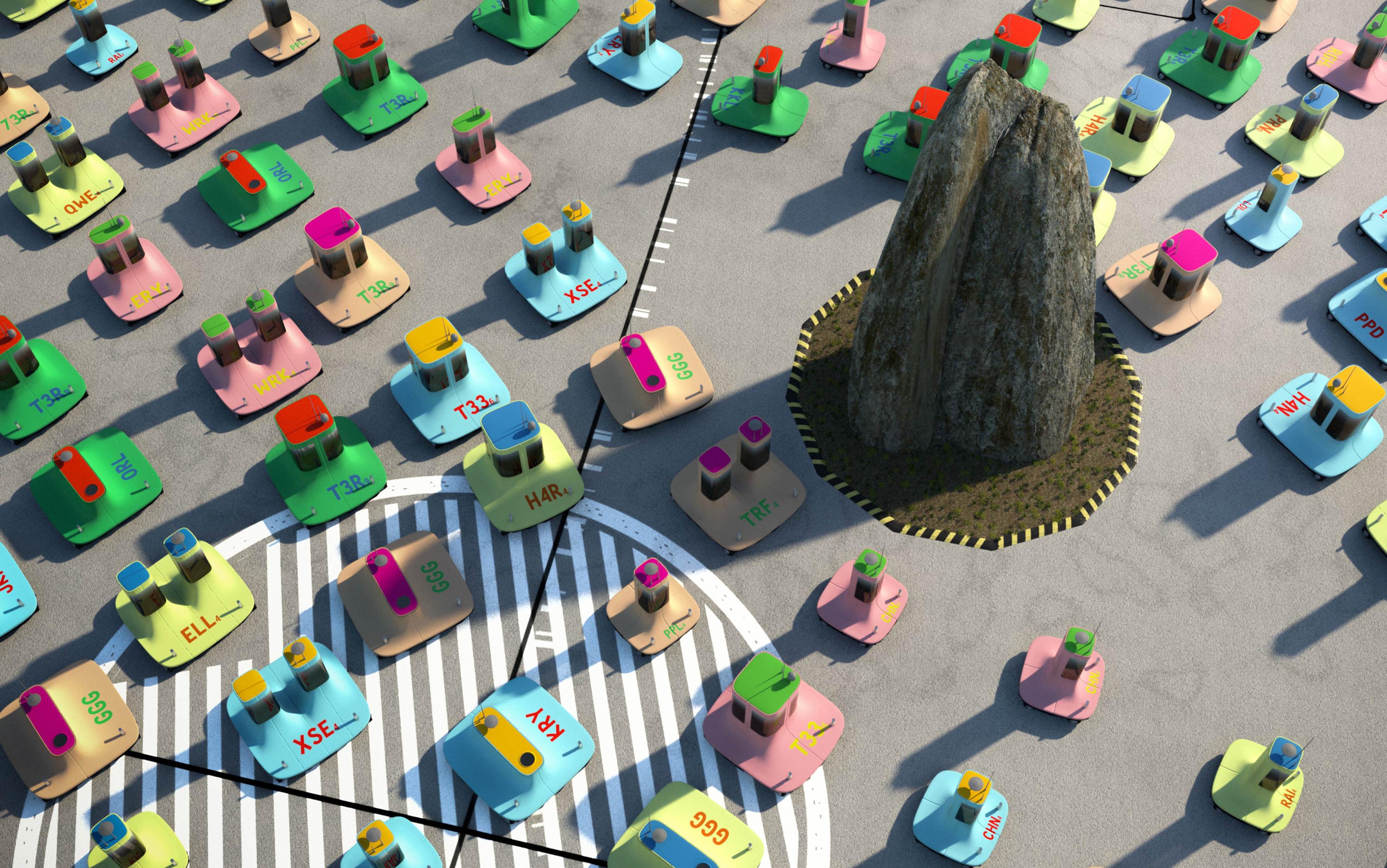

There are plenty of other examples of this effort to spur us to new thinking. In 2014, the Near Future Laboratory, a US-European design studio, published the TBD Catalog , an entire compendium of possible future products, from drone dog-walkers to environmentally sound seed-based feedstock for a 3D-printer. Other designers are committed to making actual objects or convincing mock-ups to think with. Either way, it is the detail that diverts. The 3D-printer cartridges, complete with model numbers and prices, look close enough to real adverts for things you’ve already bought to carry conviction. These finely textured depictions of the potential accoutrements of the future stimulate discussion in ways that earlier efforts to imagine technology often fail to do. They might even offer a more effective way to create futures we actually want.

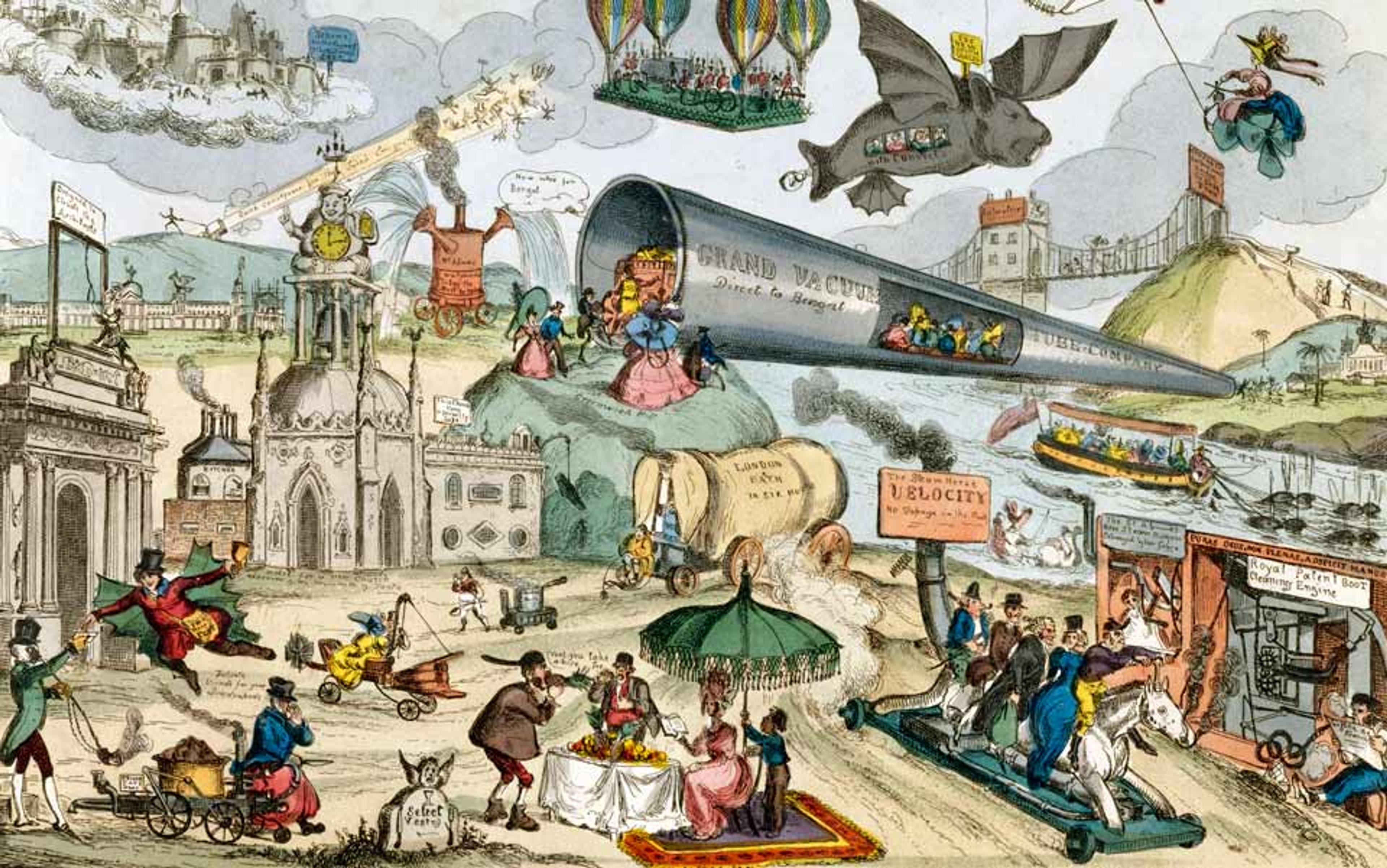

Design fictions draw on a long tradition of technological storytelling. Every technology starts with a story. We don’t know how the first hominids who fashioned a hand-axe from a flint shaped their thoughts, but the very action of flint-knapping implies a plan for the future: the result will be better, in some way, than the flints already to hand. So it is with all technologies. ‘A tool always implies at least one small story,’ writes the historian of technology David Nye in Technology Matters (2006). It begins in the imagination, and that imagining extends to what the tools will help us to achieve.

These stories can be as dry as a patent, or as fanciful as a commercial for some new gadget that will magically endow your life with the shining perfection of the product you are being sold (Google Glass, anyone?).

They are also interwoven with more familiar kinds of science fiction. The ties between scientific speculation, technological imagination and sci-fi are close, and complex, even if genuinely new ideas most often come up in the tech arena first. Arthur C Clarke is often cited as a techno-visionary for his ideas about geostationary communication satellites, but these were first outlined in 1945 in a technical essay, not in fiction. And yet the causal chain can run in the other direction: Clarke’s road map to the planets fundamentally shaped NASA’s space policy in the 1960s and, earlier, the pioneers of rocketry drew heavily on the fictions of Jules Verne and H G Wells.

Often the imaginings of sci-fi and technology work as an echo-chamber, reflecting ideas back and forth, with tech innovators claiming sci-fi inspiration as a way of communicating what their devices might do. Martin Cooper, the US engineer who led the team behind the first cell phone – demonstrated in 1973 – happily told reporters it was inspired by the Star Trek communicator; yet, at the time, he had been working for Motorola on hand-held police radios, and the mobile phone was a simple extension of that idea. But name-checking Star Trek was a good way to get people’s attention.

Sci-fi media can be astonishingly effective at promoting possible technologies. This takes on a new dimension in film, which trades in realistic depictions of new tech to underpin fictional worlds. Sometimes this cinematic realism is directly exploited by innovators. The computer interface that Tom Cruise’s character uses to manipulate data with gestures in Minority Report (2002) was based on designs by John Underkoffler, a former MIT Media Lab researcher in visualisation who was working towards just such an interface. Although the film’s narrative was dark, the interface caught people’s imagination, and Underkoffler used its cinematic impact to help secure investment in his research.

Such ultra-realist depiction of possible technology, what David Kirby in Lab Coats in Hollywood (2011) calls ‘diegetic prototypes’, is an unbeatable way to promote a new technological possibility. As Kirby writes in a 2009 paper for the journal Social Studies of Science: ‘cinematic texts require technologies to work. And, in this case, visual realism was achieved by enlisting help from people who wanted to develop precisely what was being depicted.’ It is a new kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, he says, ‘creating “preproduct placements” for technologies that do not yet exist’.

When promotional efforts like this work well (for technology advocates), sci-fi’s baleful warnings can seem less troubling, even when lodged firmly inside the culture. The dark becomes light. Think of how the 5 million-plus children born so far via in vitro fertilisation have dispelled the dystopic shivers conjured by Aldous Huxley’s hatcheries in Brave New World (1932).

Minority Report is not about critical design. In good design fiction, the possibilities are left open

But techno-Jeremiads can also hobble discussion of actual technologies in the making, by polarising the debate between pro- and anti-factions. Sometimes, this creates serious obstacles to introducing a technology. Think of how GM foods are often depicted as either essential to save a burgeoning population from starvation, or else as ‘Frankenfoods’ that jeopardise health and environment while enriching corporate agribusiness.

Design fiction’s efforts to create imaginative realisations of technology, which consciously try to evoke discussion that avoids polarising opinion, have a key ingredient, I think. Unlike the new worlds of sci-fi novels, or the ultra-detailed visuals of futuristic cinema, their stories are unfinished. Minority Report is not about critical design because its narrative is closed. In good design fiction, the story is merely hinted at, the possibilities left open. It is up to the person who stumbles across the design to make sense of how it might be part of a storied future.

Consider a project created by the designers James Auger of the Royal College of Art and Jimmy Loizeau of Goldsmith’s College, both in London. A small robot sports a mechanism that unwinds a roll of flypaper. Flies trapped on the paper are scraped off at the end of the track, and fed into a microbial fuel cell. The cell powers the roller and also a small digital time display on the front of the machine. This ‘carnivorous domestic entertainment robot’, introduced to the world as a series of realistic images in 2009, drew strong reactions online, from invocations of The Matrix to the commenter who said: ‘I can’t wait until I can throw my neighbour’s dog into the trunk of my Prius to get to work.’ Seeing an unfinished story, people responded by supplying their own scripts.

In one way, this was a success for Auger and Loizeau. The flypaper-equipped robot is a technically plausible way to start a conversation. But it still didn’t quite achieve the kind of careful, critical conversation they hoped to begin. Biomass as an energy source is all very well, but a mechanism feeding off small corpses diverts debate into the extremes of horror or levity. Popular techno-cultural tropes that get reflexively invoked this way – killer robots for electro-mechanical devices, Frankenstein’s monster for biological creations – take up so much bandwidth that they squeeze out more nuanced responses.

Design fiction’s proponents want to craft products and exhibits that are not open to this simplified response, that fire the imagination in the right way. That means being not too fanciful, not simply dystopian, and not just tapping into clichéd science‑fictional scripts. When it works, design fiction brings something new into debates about future technological life, and involves us – the users – in the discussion.

Athony Dunne and Fiona Raby are leading theorists and practitioners of critical design, and partners in the design studio Dunne and Raby in London. In Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming (2014) they survey pretty well the entire field, its forebears and its offshoots, looking for projects with something of art’s power to disturb. ‘Critical design,’ they write, ‘should be demanding, challenging, and if it is going to raise awareness, do so for issues that are not well-known.’

The recipes for in vitro meat are a case in point, foregrounding a new approach to a technology that has been depicted before, in more conventional sci-fi narratives. Artificially grown meat became a 20th-century fixation after the French surgeon and biologist Alexis Carrel experimented with tissue culture early in the century and managed to maintain chick heart cells in the lab. Worldwide publicity for the ‘heart in a jar’ ensured that cultured protein featured in many futurological tracts. It made its way into fiction, such as Frederik Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth’s classic sci-fi novel The Space Merchants (1952), with its working class fed on meals prepared from ‘Chicken Little’ (an industrial-scale tissue culture, fed with algae grown on solar-heated ponds), right up to Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake (2003), with its unappetising headless, ready-to-eat ‘ChickieNobs’.

there might be cheap, mass-produced meat, cultured in massive facilities in the countryside

Both those stories had staying power, but The In Vitro Meat Cookbook is more provocative still. It offers 45 recipes – enough for several weeks’ dining. You can’t cook them yet, says the publicity, but ‘they’ve all been developed with strict culinary rigour’. It sounds as if Heston Blumenthal had been on a visit to an advanced tissue‑culture lab. And like some of Blumenthal’s own novelties, this playful/serious compilation sets the mind working in new ways. The recipes and ingredients here help bring home the idea that if this barely existing technology (I was going to say embryonic but that risks an unfortunate confusion) develops into real products, there will be complex choices to make about which ones to use.

Mensvoort and Grievink supplement their recipes with speculative essays, including a 2025 vision of ‘The Carnery’ – a foodies’ paradise with an extensive menu of meats cultured on premises, and in vitro leather seats. The possibility of substitute meat production not involving animals is, um, fleshed out here in impressively convincing detail. The same essay suggests that there might be cheap, mass-produced meat, cultured in massive facilities in the countryside. Mid-range products would come mainly from local carneries in cities, while a few restaurants would operate micro-carneries the way that some now run micro-breweries, or make their own sourdough. This is design fiction vividly telling us to begin thinking about which new products we might choose to sample now, before they materialise, and about how to take the technology into our own hands.

But what happens when genetic manipulation is taken to a new level in what is known as synthetic biology? This, when it comes into being, will mark an epochal shift. We have spent around a century and a half getting used to the power of evolution by natural selection, which accounts for the wealth of living forms and their appearance of having been designed, without any need for a designer. Now there is every prospect of bringing design, in the proper sense of the word, back into biology.

At present, public debate about modifying living things to serve human projects remains dominated by visions of monstrosity, as witnessed by debates around GM food. Even genetically altered micro-organisms tend to be presented as super-germs. We need ways to envision a brave new biological world, ways that lead to real debate about balancing costs and benefits of realistically conceived projects. The question is, can design fiction help? According to a new book of collaborations between synthetic biologists and artists, it can.

Synthetic Aesthetics (2014), a multiply authored bio-design manual, offers a series of novel responses to scientific visions of re-engineered life. It covers the range from art pieces to design fictions, including plants modified to grow components of a herbicide dispenser; self-healing building materials; packaging that grows healthful nutrients to improve food products when you add water; and cheeses made by bacteria harvested from human skin and then named for their owners (Daisy’s Armpit, Philosopher’s Toe). While not involving any speculative science or technology, these cheeses nicely embody the spirit of the project.

The biologist Christina Agapakis, now of New York University, and the Norwegian artist Sissel Tolaas swabbed microbes off the skin of the book’s various authors, from their armpits, hands, toes and noses, in order to ferment milk. Reassuringly, perhaps, it was ‘organic pasteurised whole milk’. After an overnight incubation, they found cheese-in-the-making, then did what regular cheese-makers do, and separated the curds from the whey. The result was a collection of eight cheeses, ‘not the aged masterpieces of artisan cheese-makers, but microbial sketches, capturing some of the ecological diversity of different bodies and different body parts.’ They produced, they report, ‘a wide range of smells’.

It would be unwise to eat any of them, as their initial bacterial load was undefined – although each one was analysed in detail later on. But the reactions when they were passed round a lecture theatre for sniffing were still revealing. As one of the instigators of the project, the UK designer and artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, writes:

The audience passed them along, tentatively smelling each cheese, some trying to distinguish themselves with a measured air of objectivity by comparing smelling notes with their neighbours. For others, the small, white, moist cheeses were just too much, transgressing accepted boundaries of decency…

She reports that ‘Daisy Armpit’ was judged the best-smelling preparation, with ‘a fresh, yoghurt-like aroma’.

designers ‘test a near future by creating product manuals to probable improbable things’

For me, the human-cheese experiment displays the quality that successful design fiction needs. It proposes a different world, one in which we are not disgusted by human-derived bacteria but happy to consume cheese made with their help. And the existence of the various real cheeses effortlessly fulfils the essential condition for more fictional efforts in this vein. As the UK futurist Paul Graham Raven wrote: ‘a design fiction has to believe in itself, or at least give the impression of believing in itself’.

As design fiction comes to be recognised as a distinctive activity, it will continue to find new forms of expression. The US design theorist Julian Bleecker of the Near Future Laboratory suggests that the TBD Catalog with its realistic depictions of fictional products models a different way of innovating, in which designers ‘prototype and test a near future by writing its product descriptions, filing bug reports, creating product manuals and quick reference guides to probable improbable things’. The guiding impulse is to assist us in imagining a new normality. Design and artistic practice can both do that.

Oron Catts, director of the ‘biological arts’ lab SymbioticA, and Ionat Zurr, an artist and lecturer, both at the University of Western Australia, describe Synthetic Aesthetics’ compilation of future visions as artistic expressions that ‘offer glimpses of the possible and the contestable; works that are neither utopic or dystopic but rather ambiguous and messy’. This is the kind of subtlety that tends to get hammered out of Hollywood screenplays, but can flourish in the more diverse ecosystem of design.

Design fictions are not a panacea for some ideal future of broad participation in choosing the ensemble of technologies that we will live with. Most future technologies will continue to arrive as a done deal, despite talk among academics of ‘upstream engagement’ or – coming into fashion – instituting ‘responsible research and innovation’. The US Department of Defense, for instance, and its lavishly-funded, somewhat science-fictional Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has an extensive catalogue of research and development (R&D) projects on topics from robotics to neural enhancement, selected according to a single over-riding criterion: might they give the USA a military advantage in future? DARPA’s Biological Technologies Office tells us, in a ghastly combination of sales talk and bureaucratese, that it is ‘looking for the best innovators from all fields who have an idea for how to leverage bio+tech to solve seemingly impossible problems and deliver transformative impact’. Here, as in other fields, military, security and much commercial R&D will probably go its own way, and we’ll get weaponised biology whether we like it or not.

For the rest, though, there is a real contribution to be made through a playful, freewheeling design practice, open to many new ideas, and which is technically informed but not constrained by immediate feasibility. There are already enough examples to show how design fiction can invite new kinds of conversations about technological futures. Recognising their possibilities can open up roads not taken.

Design fiction with a less critical (and more commercial) edge will continue to appeal to innovative corporations anxious to configure new offerings to fit better with as yet undefined markets. Their overriding aim is to reduce the chances of an innovation being lost in the ‘valley of death’ between a bright idea and a successful product that preys on the minds of budget-holders.

But the greatest potential of this new way of working is as a tool for those who want to encourage a more important debate about possible futures and their technological ingredients. This is the debate we’re still too often not having, about how to harness technological potential to improve the chances of us living the lives we wish for.