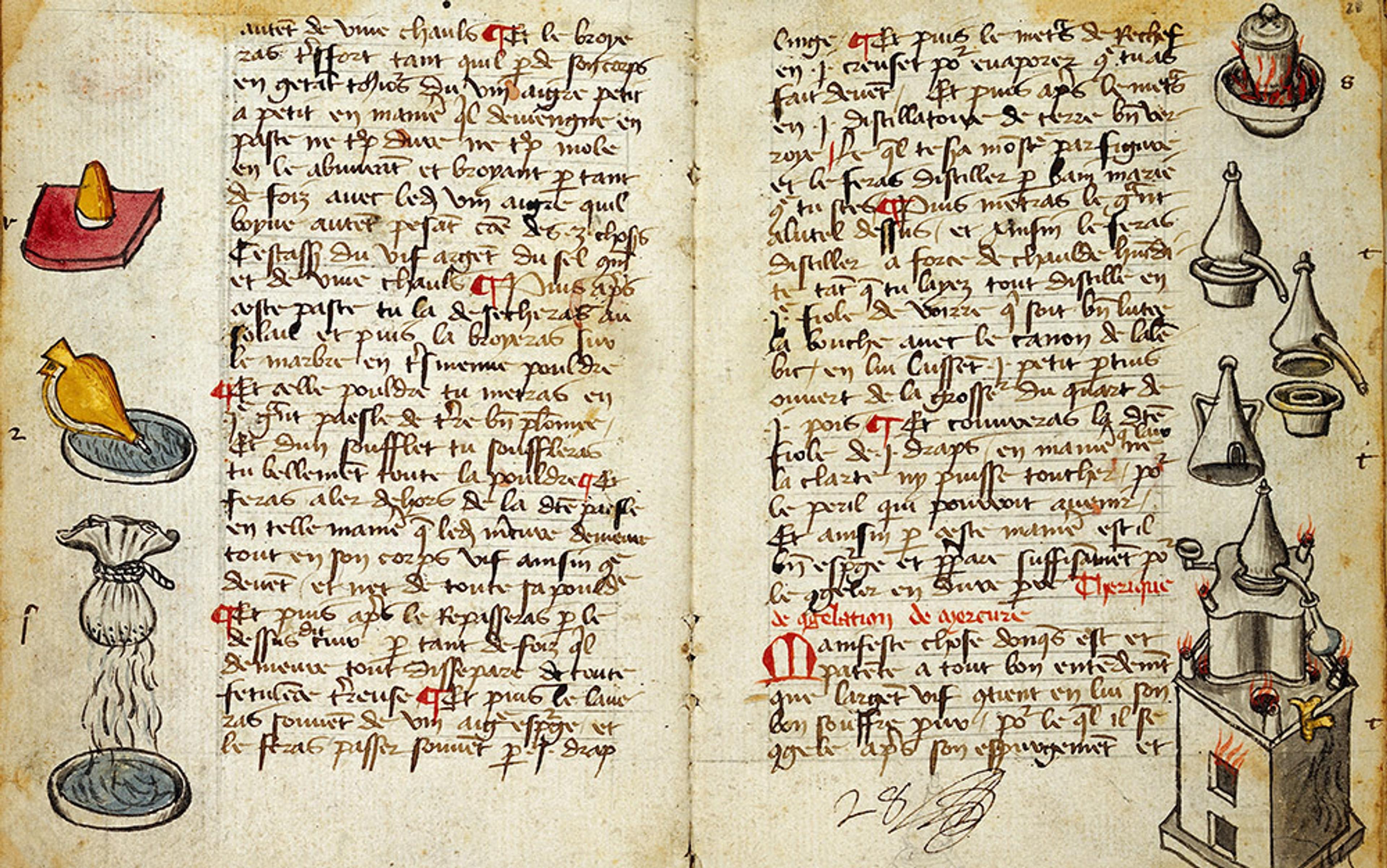

In early 16th-century France, François Rabelais, who had already made his reputation as a doctor of theology and of medicine, a scholar and a scallywag, turned his hand to novel-writing. Several years, and several hundred pages later, he loosed Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532-64) on the world. Driven by an insatiable hunger for both food and knowledge, endowed with great intellectual as well as physical brawn, and prone to laughter as seismic as an earthquake, the eponymous father-and-son duo overwhelm. No matter how you approach them, they are volcanic and titanic, immense and elemental.

In a word, they’re … well, grotesque.

And this is how Rabelais wanted it. For the good doctor, grotesqueness was not an insult, but instead an insight into the human condition. More than half a millennium later, in a world dominated by indignation and outrage, and largely abandoned by laughter, a dose of the grotesque might help to better digest events, if only by having a good – and right kind of – laugh.

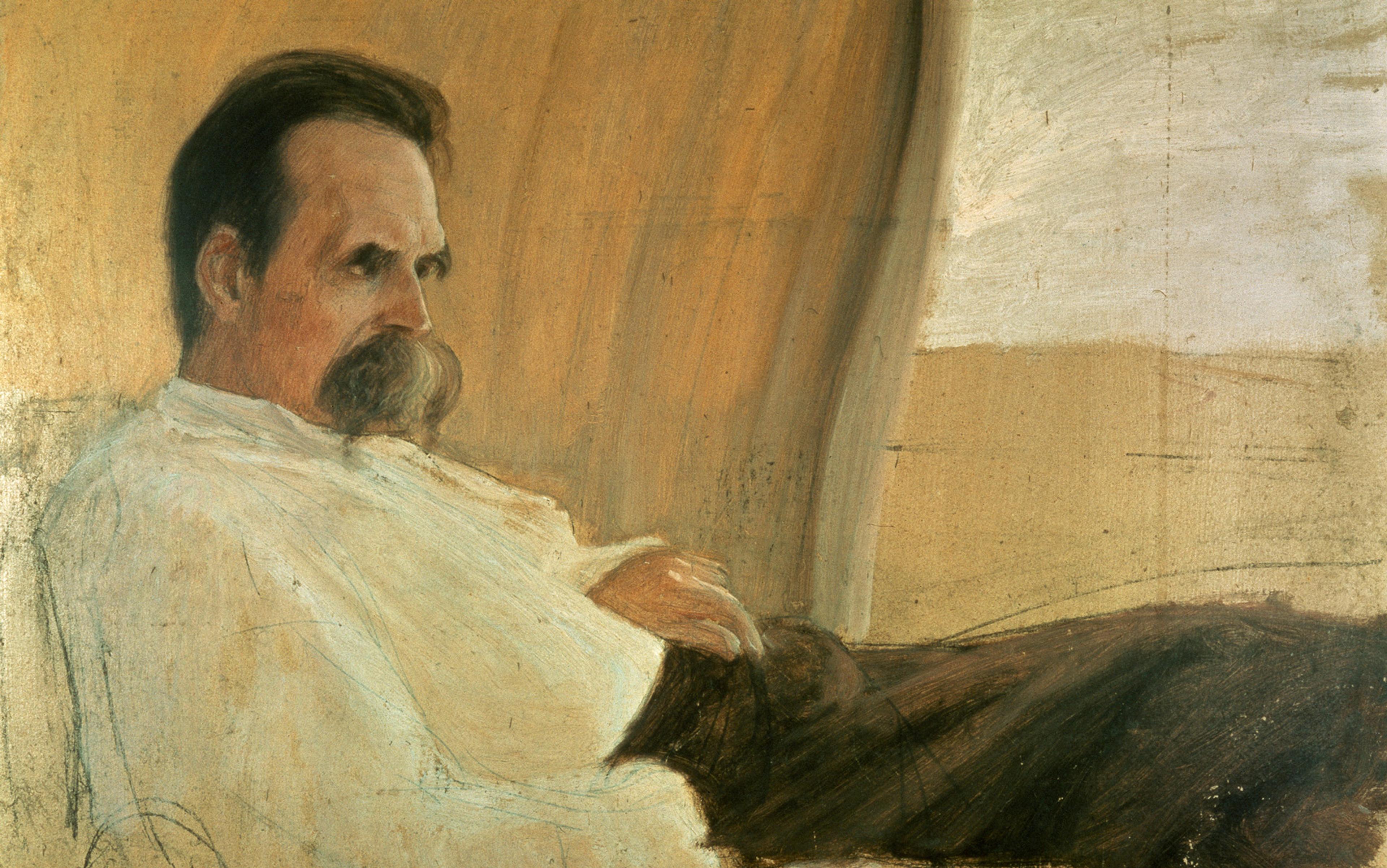

Fifty years ago, the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin presented Gargantua and Pantagruel as a unique and foreign world, at once beautiful and repulsive. In his landmark Rabelais and His World (1965), Bakhtin suggested that the laughter resounding through Rabelais’s work was particular, and practised at specific moments. It is a kind of laughter that, like any of the countless dialects or languages over the millennia, withered and died. The possibility of reviving Rabelaisian laughter is as daunting as, say, reviving the Livonian language.

Laughter is no different than political systems, commercial relations or artistic practices: it evolves over time, the result and cause of material and social transformations. For medieval man, laughter was the great leveller. Preceding Martin Luther’s priesthood of all believers was Rabelais’s priesthood of all belly-laughers. Inclusive and communal, laughter left no one untouched; no less universal than faith, it was a bit more subversive. In fact, as Bakhtin notes, late-medieval laughter marked a victory, albeit temporary, not just over the sacred and even over death; it also signalled ‘the defeat of power, of earthly kings, of the earthly upper classes, of all that represses and restricts’. For medieval man, laugh and the whole world laughs with you – or else.

Commercial interests and political institutions have, in our own age, hijacked carnivalesque events such as Mardi Gras, flattening them into carefully policed occasions marked by bar-crawling and souvenir-hawking. In Rabelais’s age, however, carnivals were simply subversive, turning upside down the official feasts and pageants regularly staged by throne and altar. Laughter laced these festivals that larded the medieval calendar. Under the walls of castles, crowds would crown jesters as kings, while in churches the junior clergy would mock pontiffs. Lords of misrule would make a mockery of royal pronouncements and practices, while monks would subvert sacred rituals into scatological riffs. During these great pauses, the institutional machinery of feudal society shuddered to a halt, enabling the vast majority of men and women, their lives shackled to scarcity and submission, to revel in the taste of abundance and lack of inhibition.

What better reason for laughter? Not only did it defeat despair, but it also overturned the symbols of state power and violence – a dizzying liberation from time and place. The laughter provoked by carnival, Bakhtin announced, consecrates the profane and ‘celebrates temporary liberation from prevailing truth’. In this monde à l’envers, he concludes, all that is ‘terrifying becomes grotesque’.

Is it possible, though, that in our own time, the grotesque has become the terrifying?

While the grotesque is difficult to define, we know it when we see it. When white- and blue-collar workers joined student activists to protest the dehumanising values embodied by Wall Street, many of them donned the sinister mask of the anonymous anarchist hero of the film V for Vendetta (2005). The mask not only shielded their identities, it also signalled that, though these men and women hailed from different backgrounds, they shared all-too-human common concerns.

Few things are more grotesque than a murderous sociopath who presents the possibility of divine grace

This convergence of socio-professional opposites, along with their fusion of contemporary cultural references with timeless ethical demands, all of which was played out on the stage of Wall Street, fused into the grotesque. In Flannery O’Connor’s short stories, glittering with a gothic pantheon of monsters and misfits, freaks and fools, the use of the grotesque resembles that of the Occupy protestors. At the conclusion of her deeply disturbing ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’ (1953), a homicidal criminal named The Misfit who has murdered an entire family confronts the one member still alive, the grandmother. When she confusedly reaches out to him, blurting that he is ‘one of my children’, The Misfit shoots her three times in the chest. ‘She would of been a good woman,’ he declares, ‘if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.’ We are left with the sight of the old woman ‘in a puddle of blood with her legs crossed under her like a child’s and her face smiling up at the cloudless sky’.

Grotesque in this sense is a descriptive, not a pejorative, term. We run head first, O’Connor writes elsewhere, into an ‘experience which we are not accustomed to observe every day, of which the ordinary man may never experience in his ordinary life’. In these lives, fictitious or factual, ‘there are strange skips and gaps which anyone trying to describe manners and customs would certainly not have left’. Few things are more grotesque than a murderous sociopath who presents the possibility of divine grace. But, of course, this is nothing more than a possibility. Recall the last words attributed to Rabelais as he lay on his deathbed: ‘I am going to the great Maybe.’

In the world of Rabelais, the grotesque comes misshapen and in sizes beginning at XXXL, lumbering across a landscape reeling from the physically excessive and socially transgressive. Pantagruel is one of the signature creations of Rabelais: as an infant, he sucked the milk of 4,600 cows and, at each meal, drained a church bell filled with gruel. The novel’s real hero, quips Bakhtin, is the ‘gaping mouth’. However, despite referring to many scenes of defecation and urination, Bakhtin – perhaps by prudishness – declines to identify other orifices as candidates for heroism.

Like the proportions of Pantagruel, so too for the limits of festive laughter: it comprehends the universe. Carnival laughter is ‘directed at all and everyone, including the carnival’s participants’. Inclusive and communal, this laughter has a ‘deep philosophical meaning, it is one of the essential forms of the truth concerning the world as a whole’. As such, medieval laughter challenges medieval seriousness. Infusing the latter, Bakhtin writes, are the ‘elements of fear, weakness, humility, submission, falsehood, hypocrisy, or on the other hand with violence, intimidation, threats and prohibition’. As if he were looking ahead to our post-modern era as much as back to Rabelais’s early modern era, Bakhtin adds that this brand of seriousness ‘oppressed, frightened, bound, lied and wore the mask of hypocrisy’.

Striding on stage at the start of Gargantua and Pantagruel, Rabelais announces to his readers:

When I see grief consume and rot

You, mirth’s my home and tears are not

For laughter is man’s proper lot.

With Prospero-like flourish, he then unleashes a carnivalesque riptide, sending scholastic, dynastic and ecclesiastic seriousness head over heels. The deadweight of social hierarchies and the everyday dread of natural disasters were thrown over, if only for a short time. While this reversal of roles ignites bouts of laughter, it does not lead to enduring change. Turned inside out, the world of carnival paradoxically reminds its practitioners of the rightness of a world up-righted. Rather than spurring rebellion, the practices of carnival amount to little more than the theatrics of rebellion, a safety valve to release social tensions. They do not offer any way to think critically about social conventions, much less new ones. Occasions for misrule are scheduled and scripted, not spontaneous; events inscribed in the calendar, they are eagerly anticipated, then nostalgically recalled when the page of the calendar turns.

But calendars and customs cannot always control carnival. As with any liminal event worth its salt, it can lurch in an unexpected direction. In 1580, for example, the French city of Romans hosted a carnival that turned deadly. As the historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie recounts in Carnival in Romans (1979), the city’s artisans and workers donned traditional costumes and props – death shrouds and flails to symbolise the ringing out of the old season, ringing in of the new by the beating of grain. The city’s notables, already galvanised by the wars of religion, interpreted the costumes and gestures as a political threat. Rather than waiting for the world to turn right-side up again, they decided to lend a bloody hand to the process. Slipping on the traditional costumes associated with their aptly named rooster and eagle clubs, they massacred several dozen of the leading members of the artisan community.

From a sharply limited ritual, the carnivalesque was granted a four-year lease on our political institutions

Several thousand miles away, and several centuries later, the United States has plunged into a similar kind of liminality gone awry. Here, too, grotesqueness lurched from the aesthetic to the political realm during the presidential primary season. Donning costumes replete with images of Hillary Clinton in prison garb or shackles, and demanding at rallies that she be locked up, the carnivalesque at times morphed into physical violence. Those scorned or ignored by the elites insisted on their feast days during these mass rallies. On 8 November 2016, however, the carnivalesque was transformed: from a sharply limited and defined ritual, it was granted a four-year lease on our political institutions.

Since then, even our ceremonies of state – from the selection of cabinet secretaries and Supreme Court justices, to the staging of press conferences and executive-order signings – exemplify the carnivalesque. Individuals lead government departments that they had once dedicated their lives to destroying; press secretaries treat the media as ‘enemies of the people’; presidential security advisors are employed by foreign powers; presidential flaks turn the world of facts upside down, insisting that down is up and up is down.

The distance travelled between Rabelaisian and Trumpian carnivals could not be greater. Bakhtin believed that the carnival-grotesque form freed medieval man ‘from conventions and established truths … from all that is humdrum and universally accepted’. Today, however, the carnival that has been catapulted into power promises a lasting, and not passing, liberation from established truths that, until now, guided our world. Alternative fact, once the nonsense spouted by fools who were crowned for a day as kings, now informs the worldview of a man, long dismissed as a fool, crowned for four years as president. In his send-up of pre-modern scholasticism, Rabelais captures the insanity of our post-truth world: ‘Why should you not believe what I tell you? Because, you reply, there is no evidence. And I reply in turn that for this very reason you should believe with perfect faith. Faith is the argument of non-evident truths.’

Medieval carnivals existed, for a limited time, to bring forth laughter. They were haw today, gone tomorrow. The postmodern carnival, on the other hand, risks becoming no less mirthless than relentless. By grotesque gestures and costumes, medieval jesters mocked not only others but themselves; laughter was all-encompassing. It flowed down – or up – the entire social ladder.

Laughter is not among the many things that spill from the gaping mouth, housed at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, that now demands the attention of the world. His incapacity for awe, respect and shame has transformed the role of comedians in our society. They are everywhere praised for their irreverence. Yet a funny thing happened to these comics: they were crowned, by popular demand, not as kings (and queens) of comedy, rulers of a world upside down, but instead as kings (and queens) for the world right-side up, where words matter and reality abides. In a sign of just how topsy-turvy the world has become, contemporary comedians have become the defenders of reverence – a virtue, the philosopher Paul Woodruff argues in Reverence (2001), that captures the capacity to have ‘feelings of awe, respect and shame when these are the right feelings to have’.

But this newfound prominence carries a risk. Bakhtin distinguished between the laughter of the Middle Ages and what he calls ‘the pure satire of modern times’. The modern satirist, unlike the medieval jester, situates herself above the world she mocks. She is from it, but not of it. The laughter inspired by carnival, while mocking, also mocked the mockers. As for the laughter inspired by late-night comedy, it too is mocking, but too often it exempts the mocker. While it is effective, it also breeds the same disdain that characterises its victims. The measure of Rabelais’s humanism is that sarcasm is almost entirely absent in his writing.

In a phrase attributed to the dying Rabelais, he supposedly declared: ‘I have nothing, I owe a great deal, and the rest I leave to the poor.’ Here is the golden rule for the mockery of those in power: leave them laughing at ourselves no less than at them. Excuse yourself from the mockery and you run the risk not just of compromising the finer political institutions, but also our humanity.