One evening in 1992, my parents, younger sister and I sat on the fold-out futon on the living room floor, petting our cats and watching fires consume buildings in Los Angeles. The images that spilled from the screen are only vague memories now: a dark night, broken windows, police sirens echoing, people rampaging across the city and leaving destruction in their wake. I was 16 years old. Having mostly grown up in small-town Montana without access to cable television, this was one of my first experiences watching a national news story on live TV.

The event we were watching, often called the LA riots, was triggered by the acquittal of police officers who had been filmed beating a construction worker named Rodney King. The eruption took its place in a long line of other violent uprisings against racial and gender injustice – the Watts riots, the Stonewall riots, and the 12th Street riot in Detroit. In my little hometown, TV viewers were prompted to view such riots through the lens of irrational ‘crowd contagion’ – a long-debunked perspective that nonetheless pervaded the media coverage in the first days of the LA event, until deeper analysis reflected on the searing racial tensions, inequality and poverty that triggered the uprising.

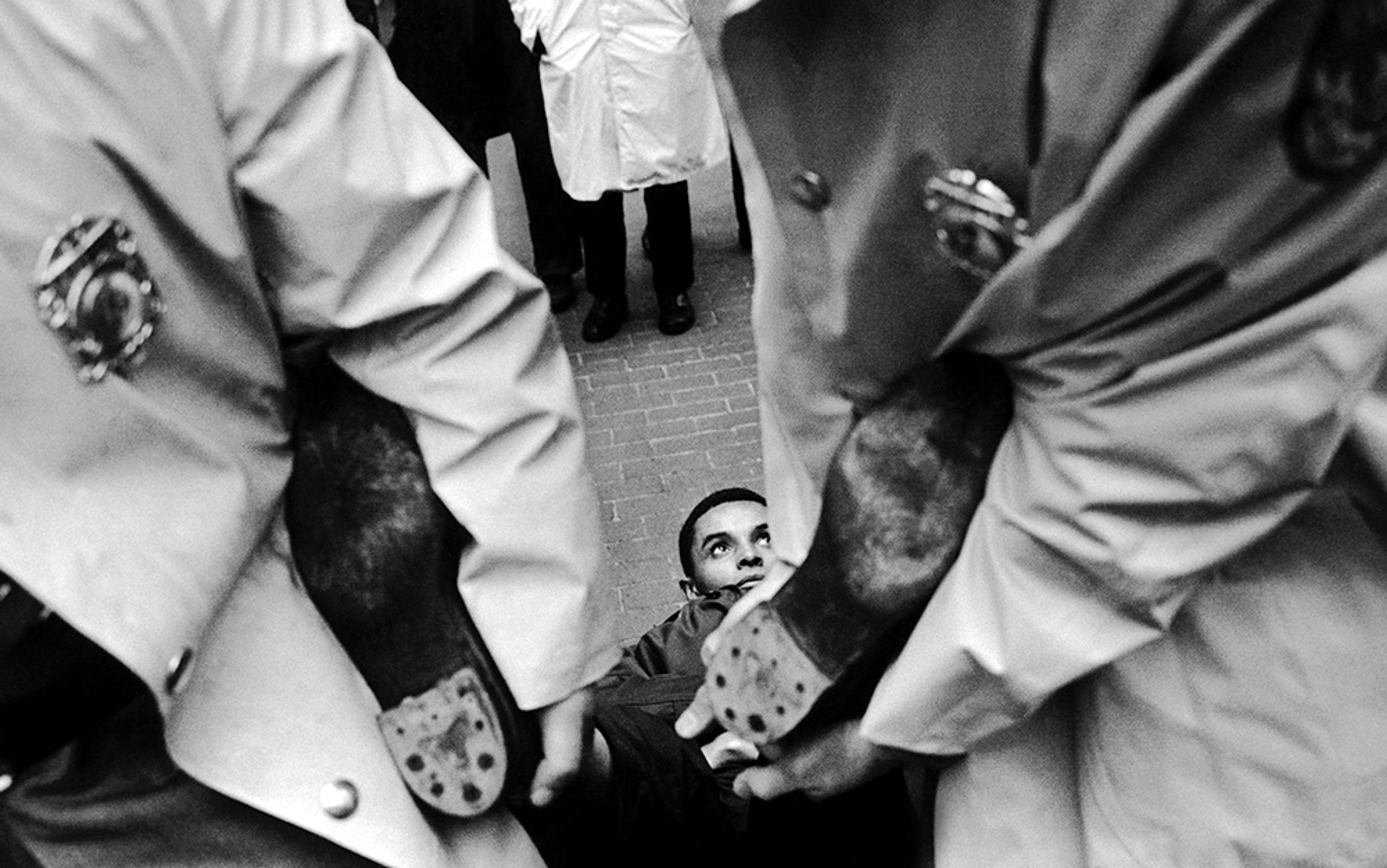

Darnell Hunt, then a postgraduate at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), focused his graduate work on the soul-searching that took place in the event’s aftermath. While I was watching buildings in LA burn on TV, he took a camcorder into the city to talk to people who saw themselves as sacrificing their own safety and freedom in response to years of injustice. While the powerful and comfortable described this civil disorder as a ‘riot’, Hunt – today, UCLA’s dean of social sciences – was pushing back to reveal concrete evidence of a government’s crisis of legitimacy. For the most part, people don’t engage in unrest for the fun of it, or because they’ve lost their rationality to a mob mentality; they do it because they feel they have no other choice.

The word ‘riot’ evokes a visceral reaction, calling up visions of chaos, disorder and offence to civil society. Once an event has been dubbed a riot, the media narrative is easy to frame: ‘these people’ are acting unlawfully, are out of control, irrational; if only they would sit down and talk. It’s this same perception that has prompted protesters in Hong Kong to insist, as one of their four remaining demands of the city’s government, that the charge of rioting be dropped against people who have been arrested for participating in mass protests against specific government policies.

The demand makes sense: when a protest is labelled a riot, it invites the automatic judgment of lawlessness and irrational, illegal behaviour begging to be quashed. Others, particularly those on the receiving end of the quashing, say that such events are last straws, emerging from communities fed up with the taking of their rights, liberties, resources and lives. In his book Languages of the Unheard (2013), the philosopher Stephen D’Arcy writes that a riot is the last resort of the disenfranchised and oppressed. He differentiates riot associated with a quest for equality from other ‘genres’ of rioting such as rioting at sports events, acquisitive rioting (looting), and authoritarian rioting, such as the Tulsa race riot of 1921, which was used to further oppress marginalised people. In fact, says Hunt, using ‘riot’ to describe both sporting events and political or social protest is a calculated political move: it colours protest or assembly as unlawful and unjustified. What we habitually call riot, writes D’Arcy, is ‘an opportunity to insist upon what official politics too often ignores: the dignity of each, and the welfare of all’.

The characterisation of ‘riot’ was born in the field of crowd psychology, whose borders became more clearly defined after the continual social unrest that shaped life in mid-1800s France. Gustave Le Bon, a French polymath and world traveller who died in 1931, had lived through the tumultuous insurrection of Paris against the French government and fought in the Franco-Prussian War. Le Bon’s book The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895) developed nascent ideas about crowd psychology that still – erroneously, say many modern researchers – inform our perceptions of crowd actions today. Le Bon is credited with influencing Adolf Hitler, Theodore Roosevelt, Vladimir Lenin and Benito Mussolini. He advanced the idea of ‘contagion’, the notion that individuals participating in a crowd action lose their sense of individuality and instead become infected by a kind of hive mind, with the group mentality spreading like a disease.

Later social scientists pushed back against the idea that collective crowd actions were irrational or spontaneous. The US sociologist Neil Smelser, author of Theory of Collective Behavior (1963), said that such acts were tied to social realities, and could be mobilised ‘in response to strain’.

The US criminologists Elliott Currie and Jerome Skolnick took things further, arguing in 1970 against the use of crowd psychology to define uprisings at all, even with caveats. They said that using its tenets to describe the agitators discredited them on a priori grounds by reverting to the top-down authoritarian thinking that Le Bon espoused. It was the authorities, Currie and Skolnick pointed out, who often acted irrationally and violently against legitimate grievances. A characterisation of mob mentality can predetermine police response, often leading to unwarranted escalation of violence.

In Hong Kong’s current ongoing protests, there was no destruction until protesters were forced to break into a building to escape the tear gas used by police, points out Clifford Stott, a professor of social psychology at Keele University in the UK. ‘If the crowd is irrational,’ Stott wrote in a 2016 paper on Le Bon and crowd psychology, co-authored with John Drury, ‘there was no point in reasoning with it; all that was required was the use of coercion and violence to protect civilisation from its inherent pathology.’

Rioting is rooted in the unwillingness to be ignored.

How we characterise crowds depends on who commands the narrative. The Boston Tea Party, where protesters dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor in 1773 in response to a tax they disliked, is taught to US schoolchildren as one of the founding myths both of America and of our modern idea of patriotism wrapped in protest against one’s government. Its name – the Boston Tea Party, not the Boston Tea Riot – evokes joyousness and order, not anger and chaos. On the other hand, at least one British newspaper of the time called it a ‘riot’, and the British government responded with harsh laws that Americans dubbed the Intolerable Acts. If America had lost its revolutionary war, our children today would likely be taught the British perspective: rather than patriotic, the dumping of tea was unlawful and chaotic, the entire evening a riot resulting in the egregious destruction of property.

The lines between assembly, protest, riot, revolt and rebellion are probably narrower than we would like to believe, and how they’re perceived by the public has lasting ramifications. Was the Tulsa race riot of 1921 less a riot than a violent act of race-directed terrorism? Was the 12th Street riot actually the 1967 Detroit Rebellion? Should the Stonewall riots of 1969 more precisely be titled the Stonewall Uprising?

‘Rioting is rooted in the unwillingness to be ignored,’ writes D’Arcy, ‘bolstered by the confidence we inspire in one another when we fight together, when we all say “No” at once and refuse to back down, side by side … That’s why it can be such a resource for democratic politics.’ Stott argues that the point at which a protest turns into what might be called a riot is simply the point at which the power dynamic of authority is reversed, whether temporarily or forever, an echo of Hunt’s idea of a government’s crisis of legitimacy. Tabatha Abu El-Haj, an associate professor of law at Drexel University in Philadelphia specialising in the history of the US constitutional right to assemble, writes that ‘angry and leaderless crowds that form to respond to perceived abuses of governmental power are always disruptive. More importantly, the Founders fully understood this when they singled out assembly for First Amendment protection.’ Rioting, or what is perceived as rioting, has been used to forward progress for centuries, usually as a last resort.

Which is also why governments have worked so hard to suppress it. The original Riot Act, which first came into being in Great Britain in 1714, made rioting punishable by up to a year in prison. The Act gave towns legal means to force gatherings of 12 or more people to disperse. Protesters were read the oral section of the Act and given an hour to disband and head home. Disobeying was punishable by death. The oral warning was crucial; several convictions of rioters were later overturned because the sheriff or mayor had failed to include every element of the proclamation (oddly enough, the ending phrase ‘God Save the King’, which seems both automatic and the easiest to remember, was the most often omitted):

Our Sovereign Lord the King chargeth and commandeth all persons, being assembled, immediately to disperse themselves, and peaceably depart to their habitations, or to their lawful business, upon the pains contained in the act made in the first year of King George the First, for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies. God save the King.

God save us all from excessive verbiage. The Riot Act was last used in England in 1919, during a police strike for shorter working hours, and was repealed in 1973, although many places still require an oral warning to be delivered before a public assembly can be dispersed by force. The law was used by nearly every British monarch between its passing and its repeal; the Sacheverell riots of 1710, the Coronation riots of 1714, and further riots in 1715 prompted the British government to come down heavily on any gathering of 12 or more people deemed unlawful, riotous, or ‘tumultuous’.

Yet if government refuses to grant rights to the people it governs, and repeatedly shows itself deaf to the people’s wishes, what exact recourse do those people have except either to acquiesce, or to become tumultuous according to the government’s interpretation of the word? It’s easy to tell people to show up at the ballot box and make their voices heard by voting, but some of the most violent actions in history were sparked by the struggle for voting rights in the first place. People don’t engage in collective action because democracy has been effective; they engage in it because it has ceased to be responsive to its citizens. In 1992, Hunt found that when authorities in Los Angeles told people to quiet down, go back home, and use their voting power to push for the changes they desired, people’s responses were along the lines of: ‘That’s what we have been doing. And nothing has changed.’

Uprisings bring change that other strategies do not. The Guardian newspaper was founded in direct response to the so-called Peterloo massacre in Manchester in 1819. It started as a peaceful rally of more than 60,000 unarmed, mostly working-class people, including children, asking for better representation in parliament in response to starvation wages and the lack of an elected representative for their urban population, at a time when only 2 per cent of the British people had the vote. After an unsympathetic magistrate read the Riot Act (which, it seems, almost nobody at the gathering heard), the thousands assembled at St Peter’s Field were attacked by government forces with sabres, ending in 18 people dead and more than 650 injured.

Prior to the reforms in the later 1800s, those without property could not vote at all

A series of hard-fought British reforms throughout the 1800s sought to spread the right to vote and alter the unequal method by which members of parliament were elected. In 1831, the Reform Bill passed in the House of Commons by more than 100 votes, but failed in the House of Lords by 41 votes. Over the next month, massive riots – or, depending on one’s perspective, rebellions – broke out in Derby, Bristol and Nottingham. ‘[W]ith wild cries,’ wrote Harry Gill in a 1904 history of Nottingham Castle, the crowd ‘rushed at the dwellings of supposed anti-reformers and perpetrated lawless deeds … The Riot Act was then read; the constables were, however, unable to seize the chief offenders or make much impression on the moving mob.’ Parliament’s refusal to reform was the impetus for the riot, but unrest had been simmering in Nottingham for several years over low wages, high food prices, and feelings of frustration and powerlessness. One account said that Nottingham alone had seen 17 riots in 17 years.

After the crowd set fire to Nottingham Castle, the Duke of Newcastle, who owned the structure, described in his diary a mob full of ‘audacity’ and ‘impunity’. Incensed by the rioters’ actions, he refused to restore the castle, and for the rest of his life the building remained a burned-out shell near the city centre. Today, the castle is a museum; one set of rooms tells the history of the Nottingham riots, of the battle between a yearning for justice and the rebellious destruction of property.

Parliament finally passed the Reform Act in 1832. The law addressed ‘rotten boroughs’ – districts where a candidate tended to be chosen and backed by local nobility, leaving the question of competition fairly moot – and ‘pocket boroughs’, in which a wealthy individual, usually also a member of the nobility, could control the local representative to the House of Commons by owning most of the local property. Prior to the reforms that followed in the later 1800s, those without property could not vote at all, while opportunities for common people to own land and therefore have some sway over electoral democracy were few and far between.

In a debate about riot’s role in democracy in 2014, D’Arcy argued that riots are ‘part of the people’s repertoire of rebellious interventions in politics’, without which the silenced and marginalised would remain silenced and marginalised. His narrative pits the ‘public order’ faction, including police and politicians, against ‘defenders of community standards of decency and fairness’. D’Arcy’s counter-debater, Vijay Prashad – an Indian journalist and then a professor of international studies at Trinity College in Connecticut – argued that riots should, instead, be seen as ‘an outgrowth of capitalism … expulsions of anger against an unfathomable system’. Perhaps both debaters are correct. Every culture has its own struggles between haves and have-nots, and its own point at which people feel that they have no choice left but to take to the streets.

‘Unfathomable’, moreover, is an apt description for the ways in which authorities have characterised protest over time. Riot need not involve throwing rocks or bottles or burning down nobles’ palaces; it need only fall within the bounds of whatever definition government gives it. In the 1800s, the House of Lords argued that ‘rioting is an essential part of our constitution’. On the other hand, in 2016 the Standing Rock encampment in North Dakota got a different response when the state accused protesters of illegal riot for blocking roads, chaining themselves to equipment and refusing to move. The so-called rioters, aligned against a pipeline carrying crude oil from North Dakota to Illinois, are the leading edge of a definitional battle with crucial consequences both for democracy and for the future of human survival in the face of the climate crisis and environmental degradation.

Following suit, in March 2019 South Dakota signed into law vague legislation that would allow towns, the state and third-party entities working with the state to sue the supporters of any protest action that turned into what South Dakota classified as a riot. In a 16-minute press conference introducing the then-proposed law, the state’s governor, Kristi Noem, used the words ‘riot’ or ‘rioters’ 12 times, wrapping them neatly next to now-familiar trigger phrases such as ‘out-of-staters’, ‘out-of-state money’, and ‘George Soros’. The word ‘protest’, by contrast, was used just three times. The legislation floated a new concept in US law: ‘riot booster’, which Noem indicated would apply to anyone funding what South Dakota would consider a riot. A riot booster ‘does not personally participate in any riot but directs, advises, encourages, or solicits other persons participating in the riot’, including anyone contributing to a protester’s GoFundMe site. ‘We will not let rioters control our economic development,’ Noem later explained.

Uprisings are like earthquakes – tensions build up along the fault lines

While a lawsuit currently prevents South Dakota from enforcing the riot booster law, it hasn’t been repealed. And during the same period, several other states have expanded definitions of riot in response to actions such as the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota.

Nonviolent resistance has been a useful tool for advancing social justice over the past 100 years but, even when it works, staying nonviolent is no protection against accusations of rioting, as those at Standing Rock found. This situation has also sparked increased resistance in Hong Kong, where nonviolent protesters have been charged with rioting. And while China’s government has attempted to portray the actions in Hong Kong as unreasonable and unlawful, the protesters’ stated requests echo the pleas of accused rioters throughout the centuries. From Britain’s failed 1800s reform bills through to the 1992 uprisings in Los Angeles, these crowd actions protest against injustice: they call not for jobs, but for the right to elect their leaders; not for affordable housing, but for freedom.

As ‘Trey’, a social scientist in Hong Kong, posted anonymously on Comparativist.org, the current unrest didn’t come out of nowhere: ‘There is a pervasive sense that this is a “last stand” with existential stakes.’ The protesters had seen what happened in the Chinese region of Xinjiang, where at least 1 million Uyghur people and likely many more were sent to ‘vocational centre’ concentration camps and ‘their children interned in fortress-like kindergartens under state custody. The correct emotional response to what happened in Xinjiang should be anger, disgust, and horror,’ wrote Trey. ‘I wonder how much of it fuels much of the existential panic in Hong Kong.’ Nonviolent protest, he added, was clearly going to be ineffective at changing Hong Kong’s policies in the long run – even if the protesters could persuade the police to convert to their side, the Chinese army waits right across the border – yet their crowd actions continue. Riot or protest, effective or not, the actions have focused the world’s attention on the Hong Kong government’s own crisis of legitimacy. Even so, the controlling narrative will ultimately depend on the government’s response.

Uprisings, says Hunt, are analogous to earthquakes – a society can go for a long time without one but tensions build up along the fault lines, and scientists are still trying to figure out what finally triggers a big event. And if I had accompanied him while he interviewed people in Los Angeles in 1992, instead of watching news coverage from my home in the Rocky Mountains, I would have had a very different perspective on the people participating in what we now call the LA riots: not anger, but a feeling of joy, of political affirmation. A feeling that the people he talked with were taking part in something greater than themselves in the interests of justice, which is part of what makes comparison with, say, acquisitive or sports-related ‘rioting’ so pernicious. Riot, rebellion, uprising or simply ‘event’, it’s no longer enough to label protesters a mindless mob and call in the riot police. Classic crowd psychology made it easy to pathologise and delegitimise these events; modern research forces us to re-examine the underlying narratives presented by authority, to ask ourselves what’s really going on.

Abraham Lincoln called the right to peaceably assemble the ‘Constitutional substitute for revolution’, the next step in forcing government to acknowledge the people’s demands when it has otherwise ceased to be responsive to voting, speech or even the rule of law. However it is defined, and whatever its parameters and perception, sometimes riot might be necessary to reclaim and defend democracy.