Fascism begins as something in the air. Stealthy as smoke in the darkness, easier to smell than to see. Fascism sets out an ethos, not a set of policies; appeals to emotion, not fact. It begins as a pose, often a deceptive one. It likes propaganda, dislikes truth, and invests heavily in performance. Untroubled by its own incoherence, it is anti-intellectual and yet contemptuous of the populace even as it exploits the crowd mentality. Fascism is accented differently in different countries, and uses the materials – and the media – of the times.

Fascism is hostile to egalitarianism and loathes liberalism. It champions ‘might is right’, a Darwinian survival of the nastiest, and detests vulnerability: the sight of weakness brings out the jackboot in the fascist mind, which then blames the victim for encouraging the kick. Fascism not only promotes violence but relishes it, viscerally so. It cherishes audacity, bravado and superbia, promotes charismatic leaders, demagogues and ‘strong men’, and seeks to flood or control the media. Even as it pretends to speak for the people, it creates the rule of the elite, a cult of violent chauvinism and a nationalism that serves racism.

The fascism of Thomas Mair (who killed the British Labour MP Jo Cox) or the now proscribed neo-Nazi National Action youth movement in the UK is so obvious; you can see it coming a mile away. The more insidious kind is the type being nourished across today’s alt-Right and its cheerleaders among Right-wing libertarians. Its precursors are in Italy, not Germany, in the Italian Futurism that bolstered Benito Mussolini, in the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, and in the mythic Roman figure of Deus Sol Invictus.

In the Futurist manifesto of 1909, Filippo Marinetti, the movement’s poster-boy, articulated the emotional fascism from which political fascism stems: ‘[O]ur hearts are not in the least tired. For they are nourished by fire, hatred and speed!’ Steel was the archetypal material for Futurist sculpture, but there are materials of the mind, too: the steel of cruelty, the gunmetal of hatred: ‘We want to exalt aggressive action, the racing foot, the fatal leap, the smack and the punch.’

In contemporary libertarianism, there is a similar love of hatred, from the alt-Right news site Breitbart proudly publishing the UK libertarian writer James Delingpole’s paean ‘In Praise of “Hate Speech”’, to Sean Gabb who, as director of the Libertarian Alliance in 2006, said: ‘[W]e believe in the right to promote hatred by any means that do not fall within the Common Law definition of assault.’ (Gabb said this as he stepped forward to defend David Irving’s expression of Holocaust denialism.) When Breitbart’s CEO Steve Bannon moved to become Trump’s chief strategist, his appointment was cheered by the former head of the Ku Klux Klan, and approved by the American Nazi party.

Libertarianism has never been more influential – many of the most prominent public figures of the far-Right are partly if not wholly libertarian. There are, of course, differences between today’s libertarians and the alt-Right: some libertarians are horrified by the racist nationalism of the alt-Right, and the militant statism of the far-Right is antithetical to libertarian values. Yet many libertarians make common cause with the alt-Right: cheering on the political upheaval of the populist Right; defending Holocaust denial; attacking the progressive left on climate science and feminism. Both the mischievous millennial alt-Right and libertarianism alike extol the power to offend and oppress, in the name of free speech. Classical libertarian issues – the defence of open borders and free immigration; the importance of personal sexual freedom – are eclipsed as the bonds of brotherhood with the far-Right tighten, and in parallel they support the rising authoritarian strongmen.

The character traits applauded by today’s far-Right – ambition, superbia, speed, drive, spin, success and spikiness – are the qualities the Futurists valued. There is fire here but never warmth; appetite but never food. If conviviality has an opposite, it is this: anti-vivial, anti-genial and, in its treatment of the future, anti-generative.

This bullyboy mentality detests the sensibility of liberalism, and torments those they call ‘SJWs’ (social justice warriors). There should be no regulations to protect the weak, they say, and they loathe the vulnerable: the British journalist Milo Yiannopoulos, Breitbart’s star writer, having encouraged the racist and sexist abuse of the American actress Leslie Jones on Twitter, then mocked her, saying: ‘If at first you don’t succeed … play the victim.’ This attitude is proto-fascistic, to despise the victim for being vulnerable, using that weakness as a reason to treat them with contempt. Many libertarians scorn individual or cultural sensitivity by promulgating the term ‘Generation Snowflake’ to describe people who might ‘melt’ in the heat of hate-speech or who want ‘trigger alerts’ to be issued over material that might traumatise survivors of sexual abuse.

Like contemporary libertarians, the Italian Futurists saw themselves as anti-establishment – opposing political and artistic tradition – and driven, as the name suggests, forward to the future. As Marinetti wrote in the Futurist manifesto: ‘Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute.’ Libertarians, like the Futurists, loathe the past, which they associate with the natural world: the future is artificial, and they want to own it. Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley venture capitalist and Donald Trump backer, describes himself as ‘way libertarian’, and is heavily involved in the Singularity, a vision of transhumanism that promotes artificial super-intelligence to create the end of natural history.

The Futurist Luigi Russolo championed a materialist idea of music as pure noise: sound should be ‘bruitistic’, exemplified in the noise of technology and the city, as opposed to the music of history or the sound of nature. He sought to brutalise the ear with noise. Language was reduced to shout, the hate-scream that features so heavily in contemporary libertarian discourse. In design, libertarians go for the stark, crude smack of visual noise, not the sensitive subtlety of illustration.

The Futurists sought a language ‘purified’ by removing grammar. They created the poetry of noise, words released from the chains of grammar; unchain them, and pure sound could be set free. What is lost? Meaning itself. For grammar’s necessary role is to shape and sculpt significance, to proliferate distinction and difference, in the plurality of endless and beautifully diverse meaning. To the Futurists, grammar was merely a hindrance to a brutal gesture of noise. Like any good fascist, Marinetti called for the burning of libraries, museums and academies.

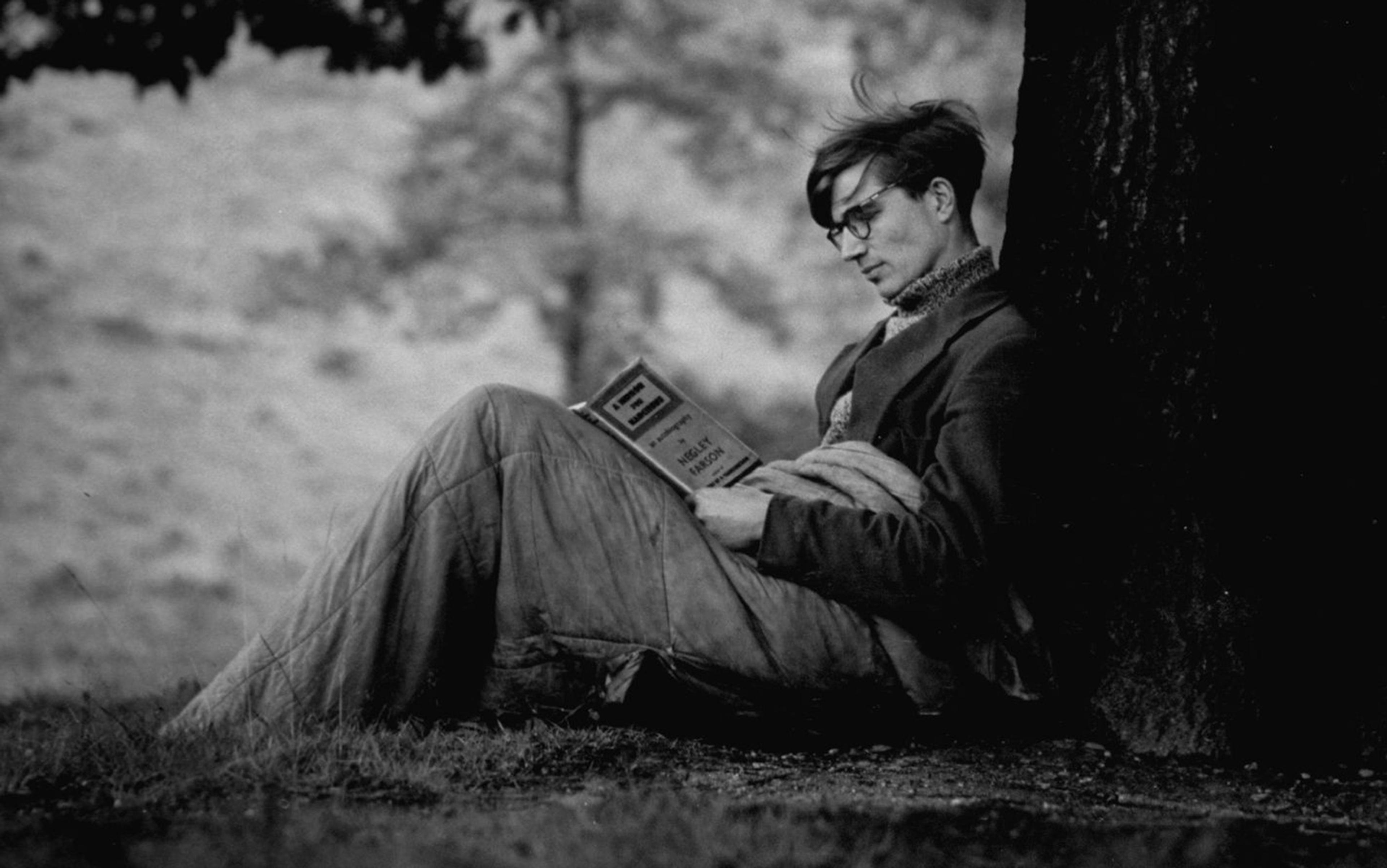

Italian Futurists (like today’s alt-Right) had a special relationship to truth. Rumour and rhetoric was their register of choice. ‘We live in a post-fact era. It’s wonderful,’ says Yiannopoulos. Yet to lie is to abuse power. It is that simple. You know you’re lying, and you also know that your audience doesn’t know, so to lie is to exploit that power imbalance contemptuously. Fascism has never been known for its intellectuality and, although book-burning seems a thing of the past, its equivalent is happening right now in the dissemination of lies about climate change, in flaming the scientists online, and trolling writers who cover the subject. In taking a deliberately anti-intellectual stance, these libertarians undermine the very idea of expertise, creating the thuggish intellectual atmosphere in which fascism flourishes. Delingpole, discussing the rise of Trump recently, remarked: ‘Part of the problem is people with degrees … there are too many of them.’

Central to the Futurist manifesto was an adoration of the machine, to the point where the ultimate aim was the technological triumph of humanity over nature. Marinetti foresaw – and was intoxicated by – the idea of a war between organic nature and mechanised humanity. Futurists fetishised cars, planes and technology in general, loving steel and loathing wood, which came gentle from the natural earth. They wanted to force the Danube to run in a straight line at 300km an hour, hating the river in its natural state (‘The opaque Danube under its muddy tunic, its attention turned on its inner life full of fat libidinous fecund fish.’)

The flight from Earth to space: the libertarian off-ground ideology of unlimited, unrestricted freedom

Such detestation of the natural world, amounting to biophobia, is one of the hallmarks of libertarians and alt-Right alike. Today’s British libertarians coalesced in the 1990s around the Revolutionary Communist Party and its magazine Living Marxism (LM), with human domination of nature their soap-box theme. Environmentalists were public enemy number one. Far-Right anti-environmentalists such as Ron Arnold, of the Center for the Defense of Free Enterprise in the US, were given a platform to rant: ‘This is a war zone,’ he wrote. ‘Our goal is to destroy, to eradicate the environmental movement.’ Meanwhile Delingpole, a climate-change denialist, recently described environmentalists as ‘scum-sucking slime creatures’ and ‘mutant slugs’ in a Breitbart article celebrating Trump’s US presidential victory, urging: ‘smite them, salt them, and crush them underfoot’. Libertarians disdain sustainability and object to environmental protection laws. Their contempt for the green movement was evident in the UK libertarian Martin Durkin’s infamously deceitful prime-time TV series Against Nature (1997), made by his company Kugelblitz, the name of Nazi-manufactured weaponry.

That Durkin’s title echoed Joris-Karl Huysmans’s iconic Decadent novel Against Nature (1884) is telling. Huysmans’s book reads like a libertarian tract, in wanting to seek freedom from the unbearable restraints of nature. ‘Nature,’ he writes, ‘has had her day … After all, what platitudinous limitations she imposes … what petty-minded restrictions … the moment has come to replace her, as far as that can be achieved, with artifice.’ Artifice was valued by the Decadent movement, while the natural world, so beloved of the Romantics (and, interestingly, the Nazis), was loathed. Libertarians and the alt-Right also adulate artifice. Yiannopoulos cites the LessWrong.com blog set up by artificial intelligence researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky: ‘LessWrong urged its community members to think like machines rather than humans. Contributors were encouraged to strip away… concern for other people’s feelings, and any other inhibitors to rational thought.’ Mere human nature has had its day.

Trump, in his climate-change denialism, makes explicit his contempt for the natural world – mere Earth – and seeks the unbridled technological artifice of colonising space. Flight is at the heart of it. The flight from Earth to space: the libertarian off-ground ideology of unlimited, unrestricted freedom, echoing Marinetti’s line: ‘Hurrah! No more contact with the vile earth!’ Contemporary libertarians venerate flight too, from libertarian writer F M Esfandiary, author of a crypto-evolutionary tract called Up-Wingers (1973), to Elon Musk’s off-world ambitions to colonise Mars. The Futurists were obsessed with the rhetoric of flight, and ‘Aeropainting’ was a major expression of Futurism. One Futurist manifesto speaks mockingly of ‘the reality traditionally constituted by a terrestrial perspective’; in contrast, painting from an aerial perspective ‘requires a profound contempt for detail’. (The contemptible details of my own terrestrial perspective, for example, might include lizard, pine marten and tomato; grace, ice and plurality.)

When the British novelist Rex Warner wanted to expose fascism’s vicious hatred of nature and of humanity, while also addressing its glamour, it was the image of flight he chose, and the rhetoric of freedom akin to the ‘liberty’ sought by libertarians. In his novel The Aerodrome (1941), the aim is to create ‘a new and more adequate race of men’ – handsome, cold, energetic, charismatic, cruel, rhetorically skilled, inhuman, cynical and fiercely anti-natural. The commanding fascist Air Vice-Marshal calls to the young airman: ‘Your purpose – to escape the bondage of time … to obtain mastery … over your environment … This discipline has one aim, the acquisition of power, and by power freedom.’ Flight is the way to escape the dank and oozing Earth, where the huddled unhygienic trudge their dumb ways. Above, superior, invincible and superb, is the airman, the Übermensch.

Trump calls climate change ‘bullshit’ and ‘a hoax’. His Environmental Protection Agency transition leader, libertarian Myron Ebell (who led a coalition of denialists to oppose the Paris agreement on climate change) speaks of the ‘myths of global warming’. In 2015, Ebell referred to Pope Francis’s encyclical on climate change as ‘scientifically ill-informed … intellectually incoherent … morally obtuse … theologically suspect … leftist drivel’. A year later, Delingpole wrote on Breitbart: ‘[T]he global-warming industry has been almost wholly under the control of crooks, liars, troughers, and scumbags’ and also: ‘Climate change is the biggest scam in the history of the world.’

Another voice now: ‘I made the mistake of thinking the truth would be its own ambassador’ says a climate scientist in The Contingency Plan (2009), a play by the British dramatist Steve Waters. If only.

Climate-change denialism is the signature deceit of alt-Right and libertarian rhetoric, top trumps in their pack of ‘alternative facts’. But the alt-Right has a host of alt-facts at its fingertips. Politics has always been riddled with propaganda, spin and cover-ups, the difference is that the libertarian mindset relishes its dishonesty; part-trick, part-game, part-combat. Over and over, all members of the far-Right use the notion of ‘free speech’ to vindicate offensiveness and outright lies.

But more: seeking freedom in all things, loathing restraint, the fact of lying becomes an ambition for breaking free of the tethers of honesty, of being ‘bound’ to tell the truth. The far-Right are masters of post-truth misinformation, and their technique is simple. Take a truth (climate change, Rwandan genocide, Serbian concentration camps) and simply declare it is a lie. (A ‘myth’, a ‘hoax’, a ‘scam’, a ‘swindle’.) Sit back and wait a minute, and a very gullible press with little editorial responsibility will happily help you tell the public that they have been conned. No one wants to feel they’ve been duped so, hey presto! You have a ‘war of ideas’. Without evidence, argument or proof. Without expertise or knowledge.

‘We will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene’ bawled the Futurist manifesto

But one libertarian lie is particularly important. In 1997, libertarianism gave a fascist, genocidal regime its actual support. At the height of Serbia’s militant nationalism, when it was torturing, raping and murdering Muslims and Croats, a small libertarian magazine called LM (previously Living Marxism) carried an article by German journalist Thomas Deichmann titled ‘The Picture that Fooled the World’. Deichmann claimed that the camps were refuges where people were protected by the Serbs. Deichmann’s fabrications led to a libel suit that forced LM to close, but they had a long afterlife: Radovan Karadzic cited them in his trial in the Hague years later in an unsuccessful attempt to fend off his conviction for war crimes, while a doctor who was an inmate at the camps recalled their impact upon him: ‘It’s hard to explain my feelings. I have no words for this behaviour. On one hand, we are trying to survive what happened to us; on the other, we have these people telling us that it is a lie.’ Though LM was financially ruined over these claims, it was quickly reconstituted as the overtly libertarian magazine Spiked to which Deichmann continued to contribute.

Lest this admiration for authoritarianism seem an anomaly, it is worth remembering that Friedrich von Hayek, one of libertarianism’s founding heroes, was an ardent admirer of Chilean dictator, Pinochet. He travelled to Chile several times, and proclaimed his personal preference for a ‘liberal dictatorship rather than toward a democratic government devoid of liberalism.’ A dictator, argued Hayek, might be a necessary transition to achieve a truly free market: he could dismantle the apparatus of state regulation and a planned economy unhindered by a political opposition.

‘We will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene’ bawled the Futurist manifesto, in language that Serbia would recall in its ethnic ‘cleansing’ for the sake of militant nationalism. Today’s libertarians follow in the far-Right’s slipstream, supporting the UK Independence Party (UKIP) with its naked nationalism (‘Believe in Britain’) and cheering Trump’s slogan ‘Make America Great Again’. As the propaganda machine whirred, Durkin produced Brexit: The Movie (2016) and made a fawning documentary about UKIP’s former leader Nigel Farage. For his part, Yiannopoulos attacks Black Lives Matter activists even as he claims to disapprove of white supremacists. ‘Behind every racist joke is a scientific fact,’ he says. Libertarians have long loathed indigenous cultures: the libertarian cult figure Ayn Rand defended the genocide of Native Americans saying that they did not ‘have any right to live in a country merely because they were born here and acted and lived like savages’. Yiannopoulos teases that he’ll turn up at Yale dressed in traditional Native American costume to speak about cultural insensitivity.

‘We will glorify … scorn for woman,’ said the Italian Futurists, and the libertarians are only too happy to oblige. Breitbart compares abortion with the Nazi Holocaust and yelps its support for Trump’s relentless hatred of women. Calling breastfeeding ‘disgusting’, Trump once remarked of women: ‘You have to treat ’em like shit.’ So free is he of ethical conventions that he makes sexual comments about dating his own daughter, while libertarian Mary J Ruwart opposed restraints on child pornography. Pandering to the pretence that white men are the ‘victims’ of political correctness – that sneering term for something the rest of us call respect – Yiannopoulos announced plans for college bursaries for white men, to put them ‘on an equal footing with female, queer and ethnic minority classmates’.

Yiannopoulos waxes freely on female biological inferiority in science. ‘Would you rather your child had feminism or cancer?’ is one of his lines. Apropos of ‘Gamergate’ – the controversy over sexism in the video games industry – he referred to ‘sociopathic feminists’. Yiannopoulos did not consider the rape threats that women received over Gamergate to be a serious issue, never mind that the games developer Brianna Wu’s home address was posted online: she received so many death threats that she had to move out of her home. Those victimised by the libertarians have often been silenced: hate speech will do that to a person. Huysmans, in 1884, noted how the supposed ‘free thinkers’ were really ‘people who claimed every liberty that they might stifle the opinions of others’.

Like Italian fascism’s ‘Il Duce’, libertarians support the ‘strong men’ – the rise of the Übermensch in the giddy upsurge of Trump and Vladimir Putin, with Farage nibbling from their fingers and Marine Le Pen in the wings. He’s ‘my daddy’, Yiannopoulos says of Trump, sounding both smirking and sinister. Warner’s airman also finds a surrogate father, a kind of godfather, in the Air Vice-Marshal, and there is something of The Godfather in this, too – a touch of the Mafia, which is becoming so apparent in the Trump camp as he gives his family key jobs around him, treats women as baubles, never forgets a grudge, and speaks a language of violence and revenge.

Tropes of Italian history are cropping up everywhere in the libertarian story: Yiannopoulos arranged for his supporters to carry him shoulder-high on a ‘throne’ to address students like an emperor with his praetorian guard. There is a flavour of the decadence of the dying Roman empire in all this – the flagrant, public, abusive sexuality that Trump boasts about; the wealth of empires at his fingertips. But the most salient parallel is the one Yiannopoulos plays for Trump: the role that D’Annunzio played for Mussolini.

D’Annunzio (1863-1938) was an attractive playboy, a poet of the Decadent movement, a racist, journalist and lover of the Übermensch – he portrayed himself as a Nietzschean superman – and a fascist sympathiser. He was a style icon of his times. A charismatic aesthete, he stood for election in 1897 as the ‘Candidate for Beauty’, and his aesthetics influenced the fascism of Mussolini, (including the use of the Roman salute). Politics was performance, and he compared himself to Nero as artist-tyrant. D’Annunzio had an extravagant, audacious style, narcissistic and self-regarding, ostentatiously sexualising himself: he had a night-shirt made for him with a hole cut out for his penis, scarlet and gold tapestry around the hole, while his slippers were patterned with phalluses. He was both self-publicist and liar: faking his death to ensure book sales. He was, like the Futurists, obsessed with aeronautics, speed, technology and war (his mansion has a battleship embedded in the side of a hill) and he was contemptuous towards what he called ‘the stench of peace’. In his praise of the idea of flight, he wrote: ‘Life on earth is a creeping, crawling business. It is in the air that one feels the glory of being a man and of conquering the elements.’

On tour, Yiannopoulos requires defuzzed peaches and roses without thorns: nature engineered to suit a jaded appetite

Yiannopoulos is flamboyantly image-obsessed. His talks are ‘shows’; his role as poster-boy for Trump, his decadence and his racism are all prefigured in D’Annunzio. They share a similar obsession with Nero – Yiannopoulos used the Twitter handle @Nero until the site banned him for life for his abuse of Leslie Jones. Both Yiannopoulos and D’Annunzio have an element of the Trickster in them, the neither-nor character, skirting the edge of fascism, not quite in, not quite out. The Trickster wants attention but not responsibility – to create chaos and then skedaddle, like Farage after the Brexit vote. Yiannopoulos declares he is not interested in politics itself, and seems to be unable to take anything seriously. In mocking Jones for playing the victim, he appears not to know the difference between playing and being – an ultimate position for an artist-trickster, for whom all life is a Gamergate, and he viciously derides his enemies for taking things seriously, for not getting his ‘joke’. But perhaps one of the most striking resemblances is the charisma.

In a brilliantly perceptive interview with Yiannopoulos for Burning Tree Magazine, Will Anderson described him as ‘an incredibly, and often disturbingly, charismatic man … I found myself instinctively wanting to clap at the crescendos of his speech, even when I knew I didn’t agree with the point he had built up to.’ Yiannopoulos’s self-conscious aesthetic looks like fetish-fascism; he ostentatiously plays Wagner and reads works on racially stereotyped sexuality, while the rider for his college tour includes defuzzed peaches and roses without thorns: nature engineered to suit a jaded appetite. There is a decadent chiaroscuro in Yiannopoulos; the sleek, wealthy, well-tailored body versus the cruelty of his political views. Artifice is his message, his meaning and his morality. He is obsessed with physical attractiveness – his own and others’ – posing, with photos of shirtless young men.

This is a trope of proto-fascism: Putin too is photographed shirtless, striking his hypermasculine poses. Le Pen poses alongside a near-naked male underwear model on her campaign trail. The alt-Right uses ‘cuckservatives’ as its hypermasculine insult to Republicans, while the alt-Right sympathiser Daryush Valizadeh (known as Roosh V) emphasises brute physicality as a hypermasculine ideal and, in line with his gender-fascism, advocates making rape legal. Marinetti, meanwhile, vilified the female body, and sought a hypermasculine transcendence of humanity, to become ‘the multiplied man’. For him, women were ‘a symbol of the earth that we ought to abandon.’

The libertarian alt-Right fits the profile of the psychopathic mindset. It sees people as objects – units, if you like. Viewing speech without consequence, guiltlessly cruel, the psychopathic mind is dishonest, deceitful, power-hungry, lacking in empathy. (According to a 2012 study, libertarians experience less empathy than others, and are less disturbed by violence.)

A crucial way in which the human mind practises empathy is in the use of metaphor; not as a literary device but as a stance of psyche, a way of understanding otherness and making stories of connection and relation. Metaphor is weirdly missing in the libertarian screeds: the literalism is choking. Metaphor comprehends the world of spirit and imagination. It deals in pluralities and the unmeasurable. It doesn’t seek to deceive but rather to augment truth. It is essential to all kinds of understanding. Metaphor is the opposite of rhetoric and works like anti-fascism in the human mind.

Libertarians loathe political correctness because it puts the brakes on bigotry, restricts racism, reins in sexism

If the alt-Right has an ideologue, it is Julius Evola, anti-semite and godfather of Italian fascism, whose ideal order was based on hierarchy and race. Richard Spencer, the white supremacist who led the ‘Hail Trump’ fascistic posturing at a Trump election celebration, invoked Evola’s vision of the Solar Civilization, a reawakening of whites, the ‘Children of the Sun’. Breitbart’s former CEO, Steve Bannon, now Trump’s closest ally, has referred to Evola as an important influence.

But if the alt-Right has an organising myth, it is Deus Invictus, the god unbound, who loathes any tether, shackle or constraint. Invictus was the epithet applied to the supreme deity Jupiter, Übergott, and to Mars, god of war, and to the empire-building Caesar. It is associated with the triumph of individualism and totalitarianism, as well as solar monism, a sky-god, singular as the Sun, and unbound from – and hostile to – the pluralities of the land. Deus Invictus drove the Italian Futurists’ demand to be free of the ‘yoke’ of the past and loosed from ties to the natural world.

Deus Invictus lies behind the libertarian refusal to be shackled by cuts in carbon emissions, behind their demand to fly free and their obsession with anti-natural technology. Deus Invictus is god of the libertarian-supported Singularity. The Deus Invictus complex drives unfettered capitalism and the unregulated industry that allows some to live like gods by making others live like cattle. Characteristics such as kindness, modesty, slowness, generosity, receptivity, pity, honesty and truth are detested by Deus Invictus, for they are the fettered emotions. In honesty you are bound to tell the truth. You are tied by respect, linked to others by love, tethered by kindness to kinship with nature, and restrained by a sense of justice and conscience. Libertarians loathe political correctness because it puts the brakes on bigotry, restricts racism, reins in sexism.

In the decadent days of the late Roman Empire, Deus Invictus, as patron of soldiers, was shown with a whip and a globe to emphasise dominance and invincibility; his solar rays were spiked. Deus Invictus is a ruthless enemy, the god unchained to scorch the earth. Deus Invictus is typified in libertarianism and personified in Trump’s solar solipsism, with his backdrop of gold curtains, Twitter-roaring against the unbearable restraints of respect or social justice. An ideology of monoism without plurality or otherness furious for its own freedom. An idiot divinity unleashed upon the world.