For more than half a century, it seemed that fascism in general and Nazism in particular had suffered their inexorable defeat and permanent annihilation in the Second World War. But with Right-wing authoritarian and ethnic nationalist movements on the rise across the world, the irrevocability of Nazism’s eradication now seems less certain. Throughout the late-20th century, one neglected body of British writing stressed that Nazism’s defeat was never inevitable, nor was its spirit entirely exorcised. Looking at that work now lets us see why postwar British writers continued to dwell on the possibilities of a Nazi triumph.

Britons consider the defeat of Nazism to be a defining national achievement, and they have been especially aware of its chanciness. That’s why every 15 September commemorates how precarious the situation appeared on that date in 1940 when the Battle of Britain was still in progress. The battle for control of the air space over England and the Channel was ultimately won by the Royal Air Force, and most Britons believe that the RAF’s victory in the air prevented the Germans from launching an amphibious cross-Channel invasion of the United Kingdom. At the time, the air battle was understood as the first stage of the nation’s struggle to repel the invading force. The prime minister Winston Churchill announced a few days after the beginning of the Blitz that: ‘These cruel, wanton, indiscriminate bombings of London are, of course, a part of Hitler’s invasion plans.’

The Germans called their cross-Channel invasion plans Operation Sea Lion. They made little attempt to conceal the operation. The whole world watched in part because Germany seemed at that point to be unstoppable; its blitzkrieg across western Europe had taken it to the coast of the English Channel. There it paused, confronting a nation that refused to make peace despite the defeat and retreat of the British Expeditionary Force from the Continent. All the action of the war had narrowed to the confrontation across the Channel. The tides and the weather would do much to determine when and if the invasion began. Would Hitler’s war machine be defeated in the attempt or deliver another deadly blow? Ultimately, Nazi Germany did not launch an invasion. But suppose the Luftwaffe had managed to defeat the RAF? Might the Germans then have started across the Channel? And if so, what might have happened then?

The question requires counterfactual historical analysis. Counterfactual history uses hypothetical thought-experiments to imagine the probable results of changes in the historical record. The hypotheses are two-part conditional statements, consisting of an ‘if’ and a ‘then’ clause: if the Luftwaffe had won the air battle, then the Germans might have successfully invaded Britain. Military historians have used counterfactual analysis for centuries. Among professional historians, they are still the most consistent practitioners. As soon as the German records for that summer had been fully declassified in the mid-1950s, military historians did not hesitate to pass judgment on the feasibility of an invasion. Their verdict: even if the Germans had won the air war, their invasion might never have launched and would have failed if it had. A Luftwaffe victory would have been a necessary but by no means sufficient condition for a sea landing.

Historians point out that the Royal Navy had more than enough flexibility and fire power to prevent a German armada from getting across the English Channel and, by cutting them off from their supply lines, could have stranded any German forces that did manage to land in Britain. German armoured divisions could not have stormed out of landing craft onto beaches because there weren’t any real landing craft at the time. The Germans’ hastily modified barges and other river boats could not have been made suitable for crossing the Channel. These facts do not, of course, rule out other ways in which an RAF defeat might have led Britain to succumb to Nazi domination. If the RAF had been badly defeated, it might have discouraged the United States’ entry into the war. Or if air victory for the Luftwaffe had eventually permitted a successful blockade of the British Isles so that the colonies could not have supplied them with food, the people might have been starved into submission. As in most counterfactual investigations, proposing the initial change allows us to see many other possible historical roads, several of which might have led to a Nazi Britain.

Imagining Nazi Britain became a popular pastime, and the fictional place was all the more plausible and vivid if people believed that they had narrowly escaped living in it. So despite the confidence of military historians, the idea that Britain was almost invaded survives. The summer of 1940 is a moment at which history and memory seem to stand at odds. Historians concur that a German invasion would have failed, but the widespread public memory remains that of a catastrophe averted at the last minute. No doubt the public memory owes something to the repeated portrayal of an invasion featured in all kinds of British propaganda.

Throughout the war, movies, leaflets and short stories featured civilians fighting off invaders, and the government helped to spur rumours about the RAF destroying German forces mid-Channel by detonating floating oil tanks to create a ‘wall of fire’. Nationwide invasion-scenario planning also played a role: widely distributed ‘stand fast’ leaflets, for example, and frequent Home Guard exercises. The Parish Invasion Committees drew up and continually revised plans for local action in the face of an advancing enemy force. The British people were encouraged to envision a Nazi invasion. They were compelled to think about where they would go, what they would take, and how they would act in encounters with enemy troops. So they have never really accepted the scholars’ assessments that it was unlikely. As late as 1992, the ‘wall of flame’ stories revived and again spread through the British press, purporting to be revelations of a closely held Second World War secret.

Britons asked what the world would have been like without their resistance to Hitler

The German invasion threat helped to reshape the British national character. It cast Britons as the saviours of Western democracy, a role that put them at the centre of world history and boosted their national pride. For more than a year after the retreat from Dunkirk in 1940, only Britain stood against Hitler. Its refusal to capitulate despite the enemy’s menacing preparations embedded itself deep in the nation’s self-image. During 1940 and ’41, the government carefully monitored civilian morale, and emphasised that the decision to fight on alone resulted from general principles, not mere expediency. Britain was not only refusing foreign domination but refusing Nazi control. To emphasise that point, the government celebrated the national traits that made Britons the opposite of Nazis.

Britain fought as a democracy, as an asylum for oppressed racial minorities, and as a defender of equal civil rights for all citizens. It protected the ideal of national self-determination for all nations. Undemocratic markers of Britishness (the House of Lords, the empire) were quietly disregarded. The royal family became less a representative of the monarchy than a symbol of all Londoners who remained in the city, endured the Blitz, and went about their lives. Many Britons believed that the most democratic and communitarian values of their country would have been extinguished worldwide if they had failed to brave the invasion. And after the war, Britons asked what the world would have been like without their resistance to Hitler’s aggression. Especially as postwar Britain evolved into a nation without an empire and massive Navy, the question of what set the British apart kept drawing on their role in defeating Nazism.

By the 1960s, the British were producing a body of literature on the spectre of a possible Nazi-occupied Great Britain. Sometimes, the occupation resulted from an invasion, and other times from a dishonourable peace. The literature of Nazi-occupied Britain offers a different kind of counterfactualism from that found in military histories. It draws out sequences of imagined events to create a picture of a society that might have existed. The books show a preoccupation with how Britain’s national character would have fared under Nazi occupation. Would Britons’ behaviour have differed from that of other Europeans? If so, how and why? The answers varied but the imagining of a Nazi Britain compelled intense British self-scrutiny.

Mid-20th-century Britain was coming to grips with its postwar loss of imperial and international power, while also experiencing the first waves of immigration from former colonies. The alternative-history books published in the 1960s and ’70s try to imagine a plausible Nazi-dominated Britain in this new world. Comer Clarke’s England Under Hitler (1960), David Lampe’s The Last Ditch (1968) and Norman Longmate’s If Britain Had Fallen (1972) all promise a ‘nonfictional’ account of ‘what German occupation would have been like’. The ‘nonfictional’ claim derives from basing their counterfactuals on evidence from three sources. First, they used Germany’s plans for organising and administering the occupation of Great Britain (devised as part of the Operation Sea Lion preparations); second, they drew information from British records of a secret official resistance movement (which had been established and recruited early in the war); and third, they used a body of research into Nazi practices from other occupied European nations. Clarke’s, Lampe’s and Longmate’s books reach the same general conclusion: though the actual wartime sacrifices were great and postwar reality had been harsh, a Nazi victory would have been much worse.

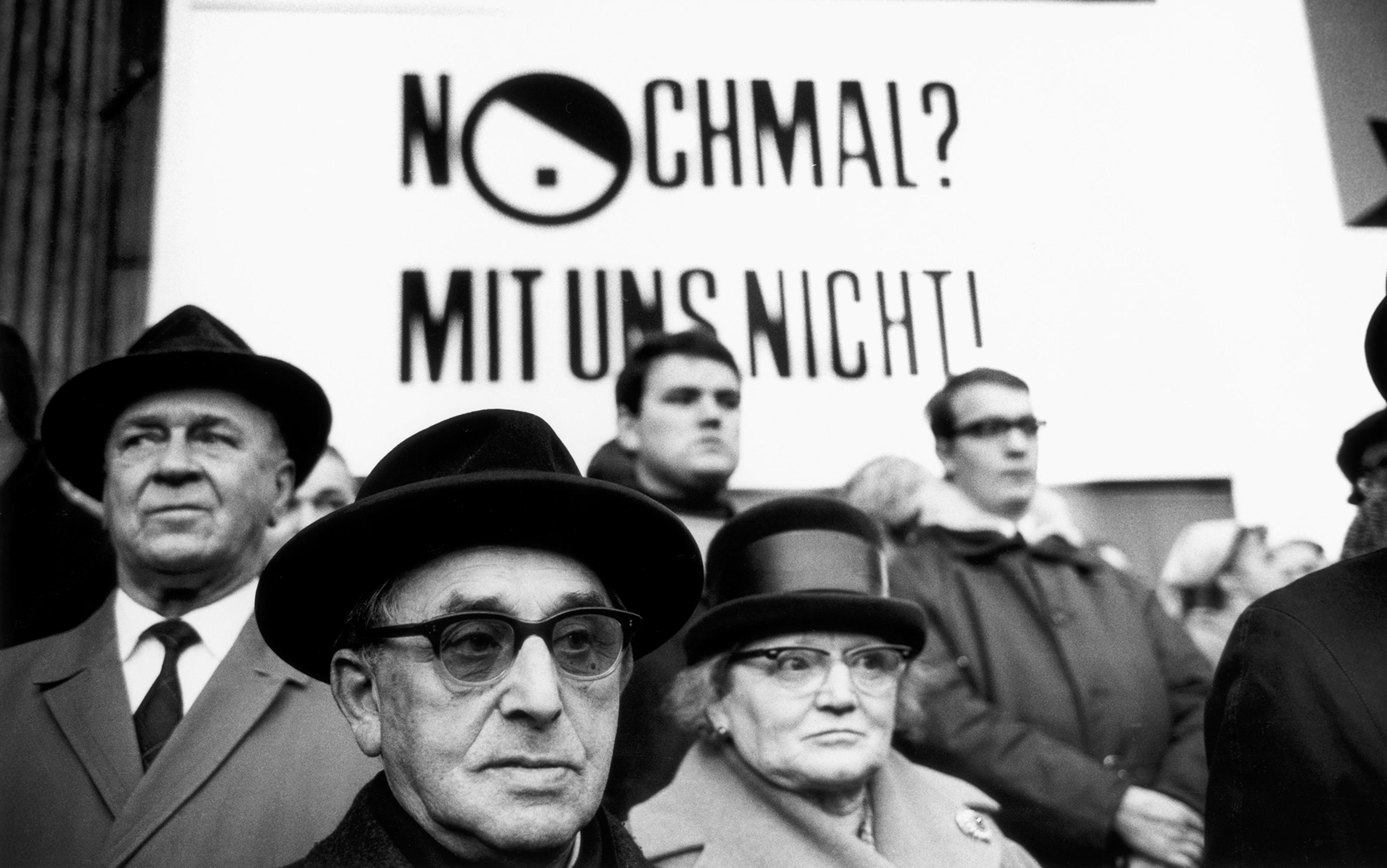

The three books also reveal how much the idea of Nazi Britain changed between 1960 and ’72. Clarke’s England Under Hitler expressed outrage that the process of denazification in the German Federal Republic had stalled in the late 1950s. Clarke meant to expose the nefariousness of the living Germans who had been most involved in planning the occupation of Britain in the summer of 1940. He wanted to show that the occupation would have been hellish, and that halting the prosecution of former Nazis invited a resurgence of National Socialism in Germany. He asked readers to take the report of his historical research as ‘a chastening reminder [of the true nature of Nazism] now that … sections of youth are daubing on walls in Germany their wretched slogans and evil swastika symbols’.

Clarke followed the lead of British wartime propaganda in presenting the Nazis as the existential enemies of all that Britain represents. He claimed that Britain, due to its strong resistance, would have been treated far worse than other western European nations. And he emphasised the uniqueness of the British national character, namely that ‘it would not have been part of the British temperament to have taken it lying down’. To prove this, he turned to the archives of the official British resistance movement, including interviews with some of its architects and projected leaders. The Nazi Britain in his England Under Hitler is brutally suppressed but also home to a brave and well-organised underground.

By the later 1960s, historical understandings of Nazi occupations and anti-Nazi resistances had grown more sophisticated. Lampe’s The Last Ditch looks at the planned British resistance movement. He agrees with Clarke about the special severity of the German orders for handling Britain. But then Lampe stresses the contradiction between imagining the occupation as hellish, and thinking of it as a possible environment for the emergence of British virtues. British resistance, Lampe insists, would have triggered the most extreme measures planned by Germany, for example, shipping all the fighting-age males out of the country. Even if the secret Auxiliary Units (the official name of the resistance operation) managed to get underground – literally into burrows that were dug in wooded and rural parts of the country – they were not equipped to do serious damage to a full-scale occupying force. Instead, the would-be British resistance could only hope to harass the enemy behind its lines. Importantly, British resistance fighters could not have been supplied from abroad, as the French had been from Britain. They would have needed to live off the land, draining local resources. This home-grown resistance would probably have proved a fatal liability to the communities among which it lived.

Germans expected the cooperation of a British civil authority

Lampe wrote during the years when the French resistance was just beginning to come under new demythologising scrutiny. Following that lead, The Last Ditch eschews Clarke’s practice of spinning stories about possible daring raids. Instead, he proposes vicious Nazi reprisals and the imposition of ‘tighter and tighter restrictions until, as a number of former Auxiliary Units Intelligence Officers today admit, great numbers of ordinary, decent Britons would have begun to cooperate with the Germans in putting down the resistance just to bring about a sort of peace’. Resistance fighters, Lampe envisions, would ultimately have turned their weapons ‘on any neighbours whom they judged to be collaborators’. He concludes on an antiheroic note: ‘to invite men into any armed underground movement is in a sense to invite them to place themselves above the law, especially when they must be trained to murder and must be armed with the weapons of assassins’. In the occupation Lampe imagined, the resistance retaliates against their countrymen, putting ‘ordinary, decent Britons’ between the Nazis and the resistance.

Longmate’s If Britain Had Fallen went further into the moral entanglements of a Nazi occupation of Britain. Like Lampe and Clarke, he searched the records for individual Britons whose lives would have been different under German rule. The members of the Auxiliary Units and the 2,700 people on the Germans’ notorious ‘Black List’, slated for immediate execution after the invasion, grabbed his attention. If Britain Had Fallen also specifically considers collaborators as a social type. It emphasises that Germans expected the cooperation of a British civil authority, and planned to delegate most of the administration of civilian life to it. The entire British legal system was to remain intact, as were the functions of teaching, policing, postal service, even customs administration.

Indeed, Longmate points out that the Germans presumed the French model of occupation by referring to ‘occupied’ and ‘unoccupied’ zones, and that the Germans’ invasion force was projected at only 250,000. They would have needed a compliant figurehead and government ministers, who might have been found, ‘somewhere among the noble families which feared a revolution and which had fawned upon von Ribbentrop or been entertained by Göring at his hunting lodge’. Longmate declined to name individuals, but his description is specific enough to bring to mind the Cliveden set of upper-class individuals, who met at the homes of the viscountess Nancy Astor, members of the Anglo-German Fellowship, and even diplomats such as Neville Henderson.

If Britain Had Fallen stresses that these British Nazis would not have been representative of the occupied British nation. Longmate portrays the struggles of British judges, lawyers, district nurses and doctors, postmen, teachers, tax collectors, mayors and city clerks pressed between the subjugated people and the Nazi overlords. If Britain Had Fallen gives us a very different Nazi Britain from Clarke’s England Under Hitler. Clarke’s model of British behaviour had been Major Colin Gubbins, the head of the Auxiliary Units, assassinating Nazi perpetrators after a village massacre. Twelve years later, in Longmate’s If Britain Had Fallen, the exemplary Briton is the anonymous civil servant, ‘a good mayor or, perhaps even more, a good town clerk’, bearing the day-to-day burden of carrying out German orders and consequently ‘likely before long to be unpopular all round’.

These darker visions of British complicity had begun appearing in alternative-history fictional works as early as 1964. They put the degeneration of the national character in a different context, indicating growing doubts about Britons themselves. Alternative-history narrative fictions are often used to populate the counterfactual worlds and explore how they would have been experienced subjectively. The film It Happened Here (1964) and the television drama The Other Man (1964) were the first works to explore the mentalities of ordinary Britons who might have been gradually led into full participation in Nazi activities. Their narratives commented on disappointments with 1960s Britain by stressing not the superiority of our world over the counterfactual alternative but the resemblances between the two.

The film It Happened Here was inspired by the fact that London in 1956, when filming began, simply did not look like a victorious national capital. The filmmakers, Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, grew up in postwar London, and were adolescents – only 18 and 16, respectively – when they began their project. They thought that, by altering a few details, London could be easily transformed into the landscape of a Nazi occupation. Theirs was the first visual representation of Nazi-occupied Britain. When they attempted to dress London as a set for their movie by draping Trafalgar Square in Nazi regalia, a number of real neo-Nazis enthusiastically joined in. Although the filmmakers kept them at arm’s length, eventually the Right-wing volunteers had a prominent role in the fictional story; they play themselves, proselytising for their racist ideology in a scene where they recruit the protagonist into the British Nazi Party. The scene stresses that Nazi beliefs were a living menace, not a mere bygone possibility.

It Happened Here was the first occupation story to feature actual British Nazis. State functionaries of all kinds, we learn, are required to join the Nazi Party, and we see the alternative world through their experiences. A struggle in the conscience of the protagonist – an Irish nurse called Pauline – replaces the opposition between Nazism and Britishness, occupiers and occupied. In order to advance her career, Pauline first accepts the Nazi ideology and rule, only to recoil when she discovers its full horror.

Most of the Nazi-Britain fictions that followed adhered to this version of the struggle. They repeated the premise that German occupiers would have found plenty of Britons eager to lead their naive and compliant countrymen into full cooperation.

The Other Man – a television play written by Giles Cooper (the preeminent broadcast dramatist in Britain) and starring Michael Caine – aired on ITV in 1964 too. Caine played a British army officer, and the TV play told an alternative history where the defeat of the British Expeditionary Force in May 1940 led to a peace treaty between Germany and the UK, including an alliance between their armed forces. Appealing to Britons’ patriotic desire to maintain imperial dominion, the Germans use the British troops to keep the South Asian and African colonies under control. Caine’s protagonist grows into a leader of genocidal anti-insurgency campaigns. The point of the tale is that Britons actually using force to retain their dominance over colonised peoples (especially in Rhodesia in 1964) were embodying the victory of Nazi ideology.

The BBC miniseries An Englishman’s Castle (1978) portrayed genocidal racial purges as a central feature of the post-1940 occupation. All of these Nazi-Britain fantasies implied that the summer-of-1940 critical moment was not really over. ‘Nazism’ loses its specific historical moorings, becoming an enduring menace, so that Britain remains at a crossroads where it must struggle against reactionary movements. However, the country no longer awaits a threat from the outside, because the characteristics touted as inimical to Britishness during the war – racial exclusivism, authoritarianism, imperialist domination – are already inside.

What defines Britishness during the controversy over EU membership?

But these warnings about the Nazi threat from within were not wholesale revaluations of the national character. At most, they challenged the idea of a unique and unchanging national essence by acknowledging the country’s political variety. Nevertheless, the Nazi-Britain narratives did preserve the summer of 1940 as a decisive moment when Britishness asserted itself through resistance, so that even if it had been shortlived, and quickly undermined by an invasion or an ignoble peace treaty, the spirit of the moment represented the best of Britons. In the 1960s and ’70s, the political Right also appealed to the spirit of 1940 in anti-immigrant campaigns. Britons, declared the Conservative MP John Stokes in Parliament in 1976, had not held out against Hitler ‘only to hand over parts of our territory to alien races’. The Left and liberal alternative histories stressed that the invasion summer represented the defeat of Nazi racism, whereas the Right-wing made it anti-foreign.

The meaning of the summer of 1940 has continued to be bound up with the question of what defines Britishness during the decades of controversy over EU membership. In the Brexit debate, those in favour of remaining in the EU have framed it as a time when Britain took the lead in a European rescue mission, while the Leavers present it as a moment of defiance against Continental interference. In 1995, the journalist Madeleine Bunting made one of the earliest attempts to tie the invasion summer to European unification. She reminded readers that the Germans actually did invade and occupy a very small portion of Great Britain in the summer of 1940: the Channel Islands.

In her book The Model Occupation (1995), Bunting reasoned that the Channel Islands’ occupation might serve as an accurate model of ‘What … could have happened in the rest of Britain’, which would debunk ‘the myth of the distinctiveness of the British character from that of Continental Europeans’. In an occupied Britain, she asserted, Britons would have behaved as they did in the actually occupied islands; they would have ‘compromised, collaborated and fraternised just as people did throughout occupied Europe’. Bunting urges Britons to discover what they truly are from the Channel Islands’ experience: typically European. Acknowledging their Europeanness would help them to accept their proper place, which is in Europe.

Bunting made her argument a few years after the UK Parliament in 1992 ratified the Maastricht Treaty on European Union, when Britons seemed on their way to becoming European. Times have certainly changed, but what lasts is the tendency to use a counterfactual thought-experiment to explore the question of whether Britons belong in Europe or not. Regardless of whether the thought-experiment concludes that Britons are typical Europeans, or that they’re intrinsically different, it starts with the same question: what would have happened if the island had been invaded and/or occupied in 1940?

This is, to be sure, a question that can never be definitively answered and, since Britons can never know how they would have acted under the heel of Nazi oppression, they are likely to continue speculating about it. Perhaps that is the one characteristic that truly does separate Britons from other Europeans.