Listen to this essay

39 minute listen

In a large hut on the edge of the Peruvian Amazon, 12 strangers gathered to transcend the modern world and find psychedelic healing. The Shipibo healer Maestro Juan, wearing a T-shirt with an illustration by Gustave Doré of angels circling heaven, was smoking a thick wad of hand-rolled mapacho tobacco while passionately telling us about tiny, invisible people who protect powerful noya rao medicine plants growing deep in the rainforest. When the seeds of those miraculous plants fall into the river, fish quickly eat them and jump into the air, becoming colourful birds. ‘Ayahuasca is similar,’ Juan explained, adding: ‘It’s not as powerful as noya rao, so you can drink it. Ayahuasca brings you into a new dimension where you can transform.’ But, as I learned during the 26 sessions I participated in at the centre where Juan worked, known as Pachamama Temple, what counts as ‘transformation’ can look very different depending on where you come from in the world.

I’m an anthropologist, and I came to Peru in 2019 to study these complex differences. For the other international participants beside me – who had arrived from Europe, North America, Southeast Asia and New Zealand – the retreat was a means of turning inward to heal personal trauma, experience shamanic visions, and forge a deeper connection with the natural world. For Juan, and the other Shipibo guides, it could be something quite different. The psychoactive molecules are the same in most ayahuasca recipes. The typical concoction is a tea made by boiling two plants that can be found across the rainforest basin: a vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) and a leafy shrub (Psychotria viridis). And yet, the experiences those molecules inspire are refracted by diverse cultural approaches and perspectives.

During the next few ceremonies I attended at Pachamama Temple, all the healers and guests drank ayahuasca as usual. But Juan stopped singing healing icaros (special songs) to each guest. Instead, dressed in a full-length robe covered in rainbow-coloured geometric kené patterns, he sung different songs to deal with the psychic incursions of sorcerers. His singing was no longer confident and loud, but now took on a cadence that was distressed, quivering and weak. He breathed heavily between verses as if the air filling his chest was thick with affliction. Then, his voice would rise again with confidence, passion and beauty. Through the sessions, the emotional tone of the singing oscillated between pain and comfort.

Juan later explained to me that jealous rivals had been magically attacking the centre – a story corroborated by other healers at the retreat. These rival shamans were telepathically spying on the centre and had directed criminals to rob Juan several weeks earlier while he was transporting a reasonable sum of cash to the local bank. As he drove on the dusty roads between the retreat and the city, Juan was confronted at gunpoint and mugged.

In Western imaginaries, the concepts of sorcery and witchcraft evoke dark and sometimes racist views of Indigenous societies being backwards or ‘primitive’. In Amazonian worlds, however, they represent an important part of holistic theories of health, emotion and power. Sorcery often signals that a disturbance has occurred and that balance needs to be restored. Many Amazonian cultures hold tranquillity and harmony as core values of society, and ayahuasca has been used to help restore balance within, for example, a village, a family or the wider ecology. Healing, in this context, is relational. Distress is understood as something that moves between people and places, not simply within the self. Therefore, accusations of sorcery may surface where relations of power or reciprocity have broken down – including around issues of jealousy, money or political dispute.

The global expansion of ayahuasca is unravelling academic ideas about the brew’s universal effects

The international guests at Pachamama Temple typically did not believe in sorcery and often ignored any sign of it. Like many of those in the Global North who turn to psychedelics as a form of psychological treatment or therapy, the guests came to the Amazon to heal themselves, learn about their own spiritual interior and connect with nature to transcend ‘modern’ problems. This treatment took place in ceremonies led by shamans seen to be relatively uncorrupted by the ills of civilisation.

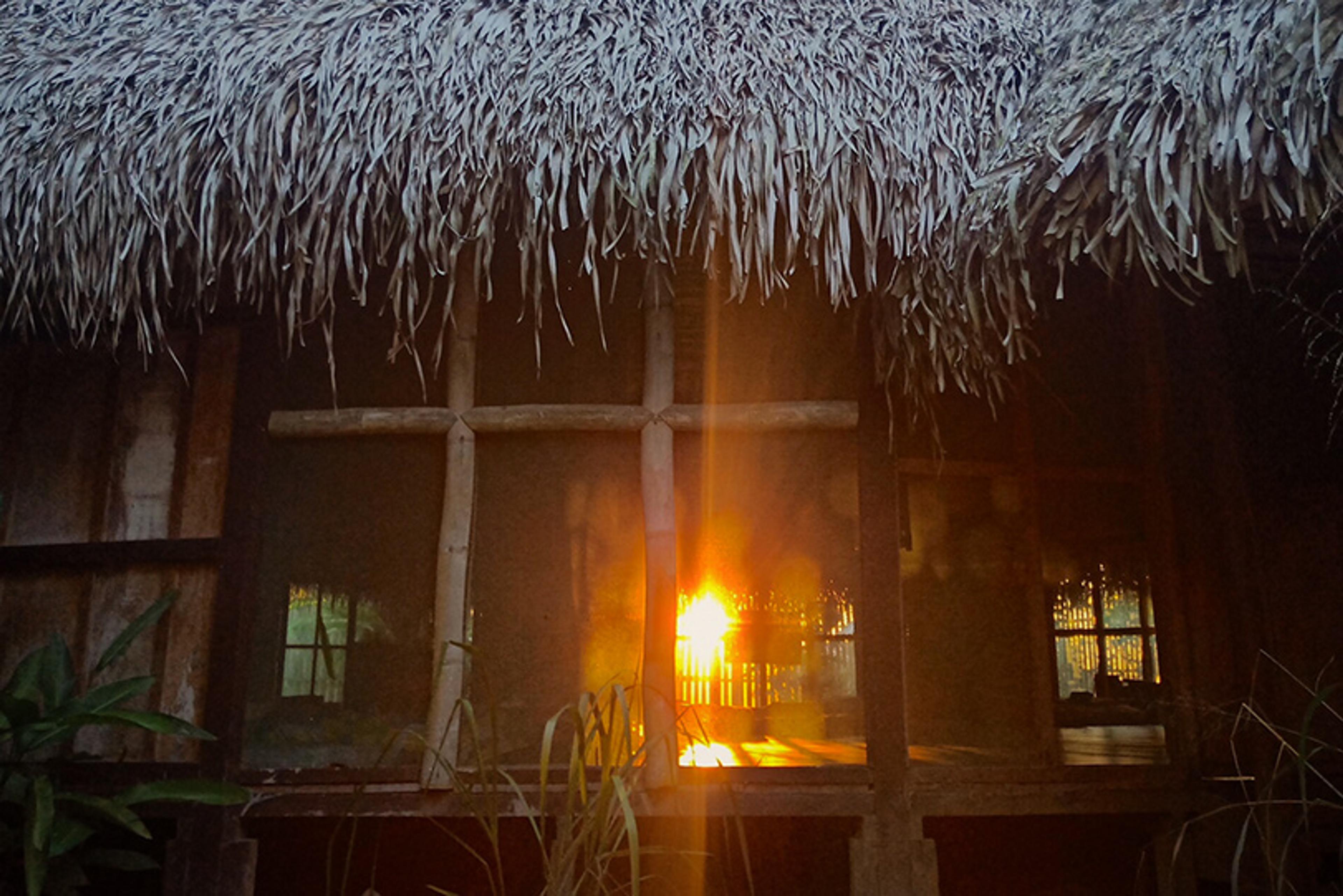

Brewing ayahuasca at Pachamama Temple in Peru, 2019. Photo by Dominik Janus

This difference in perspective demonstrates how ayahuasca can split into wildly different realities – a shapeshifting property I explore in my book Global Ayahuasca: Wondrous Visions and Modern Worlds (2024). The global expansion of ayahuasca is unravelling academic ideas about the brew’s universal effects, challenging decades of research by psychologists, scientists and anthropologists. Michael Harner, an anthropologist who lived in the Amazon during the late 1950s and early ’60s, identified purported ‘common denominators’ among Indigenous narratives of ayahuasca-drinking, such as visions of snakes, jaguars, spirits, distant places, the separation of the soul, and more. The author Peter Stafford, who wrote the Psychedelics Encyclopedia (1977), even went so far as to suggest the β-carbolines in the brew might represent a ‘pure element’ in a sort of ‘Periodical Table of Consciousness’, implying a transcultural, fundamental core to the visions.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the brew was brought to North America and Europe where it entered a burgeoning psychedelic age and became seen as a means of mind-expansion, personal empowerment and archaic revival. Even the word ‘psychedelic’ – from the Greek for ‘mind-revealing’ – privileges inner experience in ways foreign to many Indigenous understandings of the same substances. In Quechuan, the word ‘ayahuasca’ means ‘vine of souls’. For centuries or more, drinking this brew has connected Indigenous peoples in the Amazon with an invisible world, serving as a powerful teacher and ally. It has helped Indigenous groups strengthen their identities, and forge alliances with each other and with their ecological environments. It has assisted with healing, hunting, social welfare and more, representing a relational, embodied and ecological understanding of the world – one poorly captured by the English word ‘psychedelic’.

In the 2020s, we find ayahuasca used in wildly different settings to those where it first emerged in the ethnographic record. The European-based non-profit ICEERS (International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research, and Service) published a report in 2023 estimating that about 4 million people in the United States, Europe, Australia and New Zealand have consumed ayahuasca once in their lifetime. In smalltown Australia, I witnessed people purging traumas and reconnecting with nature, finding an ‘antidote’ to the disenchantment, malaise and alienation of their urban lives. In the Netherlands and elsewhere, ayahuasca drinkers embody a hybrid Christian cosmos that courses the body with the force of the brew. In Switzerland and other places, scientists are developing ‘pharmahuasca’ recipes that are administered through short-acting nasal sprays as part of the value-neutral idealism of biological psychiatry or psychotherapy. Still further, in China’s metropolitan shadows, I found entrepreneurs and executive managers secretly overcoming their blind spots with insights drawn from ayahuasca visions. Here, drinkers have visionary experiences that clarify business challenges, improve management skills or navigate complex workplace dynamics.

These glimpses show just how far ayahuasca has travelled from its rainforest origins. Across cultures and contexts, it keeps changing shape – absorbing new meanings and applications. But with so many ways of experiencing and understanding it, can anything truly universal still be said about the brew and what it reveals?

As ayahuasca circulated to places such as Australia, North America and Europe, it became associated with a movement toward ‘nature’ and away from cities. Descriptions of ancient and wise shamans living deep in the Amazon rainforest have tended to define who are the most legitimate and powerful healers. These Indigenous shamans are framed as holders of natural wisdom and ancient techniques of plant-spirit healing, which helps explain why international tourists, primarily from Western societies, keep coming to the Amazon rainforest in search of ‘authentic’ ayahuasca experiences.

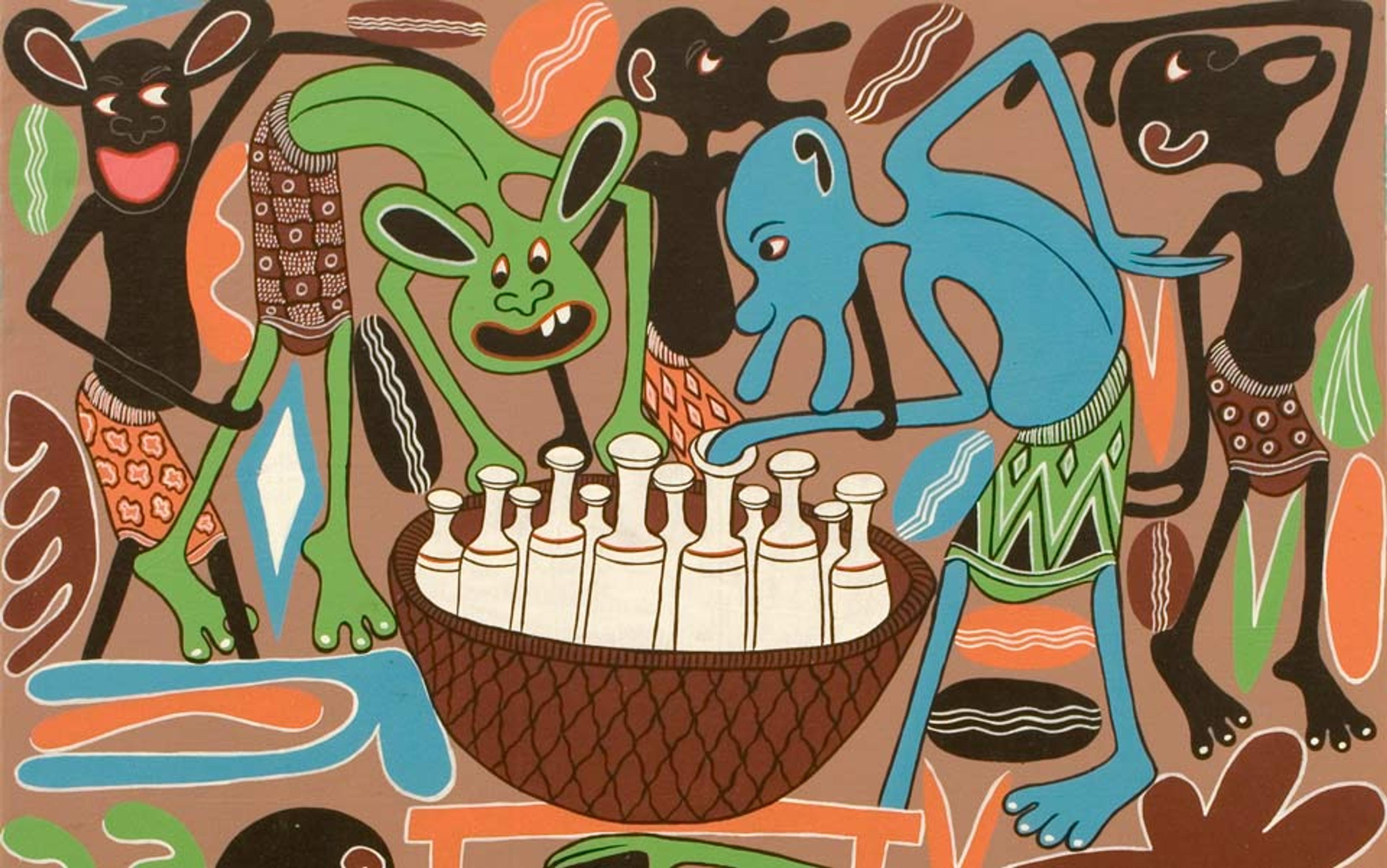

However, Amazonians hold a more complex view of the brew. They have frequently equated psychedelic experiences with their understanding of the latest technologies of the city: ayahuasca is seen as a forest cinema or Indigenous TV, and drinking it gives access to futurist underwater cities filled with skyscrapers where shamans obtain powers and a vast array of tools like X-ray machines, large bright surgical lights, hypodermic needles, as well as jet fighters and flying saucers. For marvellous visual portrayals of these technological worlds, consider the colourful paintings of the Indigenous Peruvian artist Pablo Amaringo, which show how ayahuasca can refract visionary encounters with modernity and possible futures.

In the past few decades, an ayahuasca tourism boom has occurred near Peruvian cities such as Iquitos and Pucallpa, and in other parts of the Amazon. In 2019, the anthropologist Carlos Suárez Álvarez examined Iquitos, the most popular location for ayahuasca tourism, and found that 70 ayahuasca retreat centres had served international clients that year (whereas only 30 centres were operating in 2016). He estimated that between 15,000 and 20,000 international clients had been drinking ayahuasca in the retreats annually, representing around $17.5 million in retreat booking sales. Ayahuasca centres were also operating in other parts of Peru, such as Cusco and Pucallpa, and in other South American countries.

Healers are steeped in beliefs that clash with the key marketing efforts that target international guests

In the same year that Álvarez was doing fieldwork, I spent a few months at Pachamama Temple to learn how people from different cultures used ayahuasca together. This retreat drew people from around the world who had come to drink ayahuasca with a family of Shipibo healers led by Maestra Rosa Pinedo Vasquez – affectionately known to guests as Mama Rosa. From what I’d seen in Australia and read in the anthropology of Lowland South America, I didn’t expect the brew to create the same kind of experience for everyone. I thought the mix of cultures might bring moments of connection as well as misunderstanding.

Maestra Rosa Pinedo Vasquez, 2019. Photo by Dominik Janus

Maestra Rosa Pinedo Vasquez with her son, Maestro Luis Marquez Pinedo, 2019. Photo by Dominik Janus

Many global ayahuasca retreats in Peru appear to minimise interactions between guests and Indigenous healers, most likely because healers are steeped in beliefs and contexts that clash with the key marketing efforts that target international guests. These different lived philosophies include differences in navigating the brew. Although many English-language websites encourage users to surrender and dissolve into their visions, whether blissful or terrifying, the healers at Pachamama Temple proposed a far more cautious approach. If guests encountered forms of negativity in their visions – such as scary snakes, spiders or monsters – they were told to dominate (dominar ) them and will the negativity away. The goal is to banish the bad energies and promote positivity and joyful, luminous and fragrant visions (‘fragrant’ being a reference to the synaesthetic effects of psychedelics, where aromas may convert to visions, or other senses may poetically blur).

From this perspective, the ayahuasca drinker’s bad or challenging visions are not merely reflections of their pathological mind or unresolved trauma. They may also be interferences from others, such as negative energies unwittingly spilling over from another person in the ceremony space.

These differing orientations between psychology and shamanism can be difficult to hold together in one perception. Reflecting on such challenges, the anthropologist Pedro Cesarino argues that:

Indigenous shamanism [has become] a metaphor for our dilemmas – reintegration with nature, rediscovery of the self, religion as a lost totality, overcoming the problems associated with neurosis and solipsism, among others – rather than being understood according to that which is original and specific to itself.

Yet, a novel approach has emerged in the ayahuasca tourism contexts. The healers at Pachamama Temple told me that they would rather heal visitors than locals, not simply because visitors pay around 10 times more for their services, but also because visitors are easier to heal. According to the healers, the nihue or spirit essence affecting the bodies of the international visitors is weaker and different from that affecting the Shipibo and others in the region.

Anthropologists in the 1970s, before international ayahuasca tourism existed, described Shipibo shamanistic practice as a closed cosmological system in which spirit essence must circulate and could not be destroyed. Thus, when removed from the body, the invisible pathogenic sickness that ayahuasca may reveal in colourful visions must be directed to another person. This person might be human, such as an unnamed member of a neighbouring community, or more-than-human, such as an animal or plant.

Healers are not dealing with powerful sorcery substances in foreign visitor’s bodies

By contrast, the healers at Pachamama employed a new shamanic technology that enabled them to vaporise and completely obliterate the bad energies of the visitors. One healer told me that when he drinks ayahuasca and sings over a patient, he can see the bad nihue in their body appear like a dark cloud. His magical song blasts the dark cloud until the bad energy starts raining down and drains away from the body. When I asked where the energy goes, he explained that it was weak nihue, so it just disappears. Another healer at Pachamama described the difference this way:

When I sing over a pasajero [ayahuasca visitor], my medicine penetrates their body. I can see their body and energy. We remove the bad energies, leave him healed, and open his visions. But working with Shipibo patients can be different. There is a lot of black magic here, and people come with a lot of harm. Also, many people learn bad spells. The pasajeros don’t arrive with witchcraft harms. They are just sick with mental disorders.

The healers made a distinction between two types of techniques: chamans and curanderos. The first heals foreigners; the second heals Shipibo and other locals. In the tweaked cosmological environment of international tourism, healers are not dealing with powerful sorcery substances in visitor’s bodies, nor are they required to cure illness by passing it on to another body (whether human or nonhuman). The guests have introduced a lucrative-sounding opportunity for Amazonian shamans to provide therapeutic services that are not concerned with local moral economies of tranquillity, sorcery and inequality.

Although international retreats may sound lucrative to Indigenous healers, the anthropologist Daniela Peluso points out that foreign investment dominates the ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’ of ayahuasca tourism in Peru. The result of this, she suggests, is that Indigenous people are disadvantaged and the benefits of the foreigner are privileged. This can be observed by considering the ambient poverty of many Shipibo living in Pucallpa and the wider Ucayali region. According to research by Bernd Brabec de Mori in 2014, of the 50,000 Shipibo people who live here – considered among the most internationally renowned group to use ayahuasca – as little as a few dozen earned enough to live well on the ayahuasca tourism economy. Issues of water sanitisation, food security and poor health are rampant in areas of Pucallpa and Iquitos.

So, with all this difference and cultural complexity, is there anything shared about the experiences of Indigenous peoples in the Amazon and the international tourists who visit them? One way of understanding a connection is to view the Shipibo healers working in the international retreats as merchants of wonder. The humour and happiness they expressed sometimes came as a positive surprise to the visitors.

A kind of warm happiness was on full display at the retreats I studied. I remember noticing this one evening at Pachamama Temple. The healers had arrived at the dark maloca (communal house) shortly after sunset, where international guests had completed a guided meditation for one hour and then remained in a private and introspective state for another hour. The healers got comfortable in the space, whispering to each other, giggling and joking, whistling tunes, sustaining a warm sociality. Maestro Jose opened the glass ayahuasca bottle and the pressure created a gas-release sound indicating the brew had accidentally fermented. Some healers giggled, getting ready to drink and serve a brew that would likely upset the stomach more than usual.

Maloca at Pachamama Temple, 2019. Photo by Alex Gearin

Today, ayahuasca is known globally for awe-inspiring visions, sometimes hard-earned healing effects, and hedonic tones, including beautiful and grotesque sensory worlds. Less acknowledged is how the wondrous brew entangles with moral life. Awe, as the psychologist Dacher Keltner points out, can arise when we perceive extraordinary virtue in others, and sometimes even in ourselves. He calls this our capacity for moral beauty.

Shipibo healers in the Peruvian Amazon who have mastered psychedelic plants embody a special quality called quiquin, which combines notions of ‘correctness’ and ‘beauty’, according to the anthropologist Angelika Gebhart-Sayer. Quiquin can indicate good moral character, broadly speaking, and also refers to the beautiful ‘design medicine’ that healers sing to shape the augmented senses of ayahuasca-drinking. In this way, quiquin unifies the moral and the aesthetic with vision-inducing plants. In Amazonia, the brew has assisted people in developing virtues, such as courage, kindness, tranquillity and joy, but it has also fostered qualities deemed immoral and toxic, such as those associated with sorcery and witchcraft. Ayahuasca, like wonder and awe, dances with moral ambiguities.

This moral ambiguity runs through the shapeshifting skills of jaguars, anacondas and shamans themselves

In contemporary English, the notion of wonder tends to be stripped of its ambiguous moral tones and cast as a mood to enhance positive psychology. People tend to speak of it in a positive light. Yet wonder can also occur during fearful, painful encounters. Importantly, in the context of psychedelic use, a positive version of wonder is but one possible mood among a vast emotional landscape. Moments of ‘moral beauty’ may arise across these undulating and unpredictable terrains, revealing visions of protective plant spirits, wrathful deities, futuristic realms, poignant social memories, and much, much more.

Inside the maloca at Pachamama Temple, 2019. Photo by Alex Gearin

Among Amazonian healers, this moral ambiguity runs through the shapeshifting skills of jaguars, anacondas and shamans themselves. These figures can disguise themselves by transforming their appearance, appearing helpful when they’re really motivated by other intentions. The same force that cures can also wound; the same vision that protects can deceive. What you see is not necessarily what you get, as the anthropologist Peter Rivière explained in his description of Amazonian cosmology. Transformation is not simply good or bad, but a delicate dance with powers that can turn either way.

To understand the wondrous transformative potential of ayahuasca, I later travelled to China, to participate in drinking ceremonies thousands of kilometres from Peru. Here, the brew’s moral and aesthetic ambiguities were being recast in new languages.

What initially surprised me was how certain ideas I had encountered in Amazonian shamanism – particularly the notion of shapeshifting – found a surprising resonance in Chinese thought. While teaching anthropology in mainland China, my students noticed some striking parallels. The Amazonian practice of taking psychoactive plants to shapeshift to the point of view of another species, lifeform or person made sense to them. They immediately connected this to familiar Chinese stories.

This similar-but-different motif tricks the senses while exaggerating reality to reveal the true essence of a person

Consider this scene in the classic 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West, when Monkey and the formidable deity Erlang Shen compete in a mutual shapeshifting showdown. Being chased, Monkey dives into water, becoming a fish. Erlang follows, yet is unable to spot Monkey. He thinks to himself:

The fish that released the bubbles looks like a carp though its tail is not red, like a perch though there are no patterns on its scales, like a snake fish though there are no stars on its head, like a bream though its gills have no bristles … It must be the transformed monkey himself!

This shared literacy runs deep. In Peru, the Yaminahua shaman José Choro described to the British anthropologist Graham Townsley how he perceives shapeshifting animals and plants when drinking ayahuasca. He said they appear ‘like something you recognise and at the same time they are different.’ They are, for instance, like the jaguar but without a tail, like the anaconda but with different designs, like the river dolphin but with a larger nose. This similar-but-different motif tricks the senses while exaggerating reality to reveal the true essence of a person; at least for those sharp enough to recognise.

My Chinese students drew other parallels too. While reading the Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa’s book The Falling Sky (2010), they compared his indictment of the ‘People of Merchandise’ (from non-Indigenous, commodity-driven societies) with movements in contemporary China, where youths are reimagining Buddhism as fo xi (佛系), a laid-back ‘Buddha-like’ refusal of competitive capitalism and grand modern dreams.

Many of the retreat attendees I met in Peru or at other ayahuasca retreats around the world were searching for an enchantment deemed lost to modernity. They were not seeking ways of executing a greater mastery over modern life. However, as ayahuasca has spread to global cities it appears to be increasingly used, along with other psychedelics, to optimise, boost or enhance workplace performance. This has become a well-established theme of psychedelic use in North America and Europe. As I found during fieldwork in 2019 and 2020, it is also emerging among executives and other white-collar workers in China.

For some of the ayahuasca drinkers I met, corporate contexts shaped the visions and wonder they described. These young professionals, who lived in large Chinese cities, were searching for holistic wellness, self-cultivation and a competitive edge in capitalist environments. Ayahuasca provided a new means of achieving mastery.

In China, I mostly interviewed upper-middle-class Chinese workers who were seeking wisdom from ayahuasca for their careers – my research doesn’t allow me to make any grand claims about the broader use of psychedelics in China. This fieldwork was designed to explore how utilitarian ambitions were intersecting sharply with the mystery and wonder of the brew. Additionally, some of the ayahuasca drinkers I encountered were often connected with the shen xin ling (‘Body-Heart-Spirit’) milieu, a movement that the anthropologist Anna Iskra has described as recirculating New Age spirituality in China. Some of the drinkers I met had been regularly attending shen xin ling workshops in search of holistic wellness and spiritual inspiration.

Ayahuasca is typically translated as 死藤水 (sǐ téng shuǐ), which literally means ‘dead, vine, water’. Aside from sounding spooky in Chinese, this translation is reminiscent of the Indigenous Quechua terminology: ‘aya’ means ‘spirit’, ‘soul’ and ‘deceased ancestors’; ‘huasca’ means ‘vine’ and ‘woody rope’.

Describing ayahuasca-drinking as secular and therapeutic gives it a modernist bent

During my time in China, I soon learned that the only ongoing commercial ayahuasca business operating in mainland China appears to have been largely cultivated by one person, who I will call ‘Luke’. He is a young and energetic ayahuasca specialist from Europe who, when I spoke with him, had made more than 10 trips to the Amazon region to learn from Indigenous specialists and other experts – he had also been drinking ayahuasca himself for 16 years. However, unlike the Amazonians he learned from, his approach was secular.

‘I have great respect for the different ayahuasca traditions,’ he told the 15 mainly Chinese attendees at a retreat shortly before everyone drank the brew in one of the country’s largest cities. ‘We have our own way. It’s not the shamanic approach, or religious approach, but the therapeutic approach, the secular approach.’ He described the events as specifically ‘sessions’ and ‘processes’ rather than ceremonies or rituals.

The sanitisation of ayahuasca into a secular framework is remarkably novel. However, Luke didn’t further force participants to think this way. When they described encountering spirits, gods and other worlds in their visions, he made no effort to correct them along secular lines.

Spiritual practitioners are often obliged to justify themselves in modernist contexts, as Vincent Goossaert and David Palmer explained in The Religious Question in Modern China (2011). Describing ayahuasca-drinking as secular and therapeutic gives it a modernist bent, which was Luke’s explicit intention. He told me:

To bring the plants [ayahuasca] to the modern world, sometimes it needs to be translated. If you start talking to a manager from a company who is very square-minded about power animals and mariri [spiritual substances or protective energies], he is going to think you are crazy. My background is more aligned with companies and corporate mindsets. I talk more in terms of anxiety, depression, purpose, mission, conflict.

The ‘session room’ where he conducted the evening ayahuasca sessions was in the loungeroom of a quiet housing estate. A large glowing salt crystal was on the floor in the middle of the room, surrounded by sage leaves, fragrant palo santo woodsticks, a piece of ayahuasca vine, and a pinecone. One wall was decorated with Amazonian Shipibo fabric, a large Chinese script for driving away ghosts (next to a figure of the Daoist deity Guan Yu) and an image of a Tibetan Buddha, which were all above Luke who was observing the group as the sounds of a calming Spotify playlist filled the room.

‘We have different packages and services all designed to help people transform,’ Luke explained to me. This transformative business included a core product, titled Bridging the Gap, which aimed to take clients beyond a functional state and enhance their vocational abilities. It was a leadership programme designed specifically to help corporate managers, entrepreneurs and CEOs to advance their careers and live happier lives.

Clients were supported by Luke and retreat staff in the overall goal of Bridging the Gap, wherein they sought to align an internal self, called the Monk, with an external self, called the Suit. The Monk-self was related to ‘spirit, heart, purpose and intuition’, and the Suit-self to ‘occupation, material belongings, ego and mind’. Group sessions of drinking ayahuasca helped individuals perceive and understand the gap between their two selves. Subsequent coaching sessions and knowledge seminars helped the client ‘take action’ to close the gap between the two inner selves and ‘implement change’ in their workplace and domestic life. This all results, Luke hopes, in a ‘Suited Monk’.

The ayahuasca-drinking of Ting Ting, a Chinese woman in her early 30s, incorporates this framework while also seeking to heal deeply personal trauma. After completing her university studies, she left home and moved to one of China’s largest cities. She was motivated to move partly to escape the distress of her father being diagnosed with a terminal disease, which gave him less than two years to live. About a decade after her father’s death, she attended ayahuasca retreats facilitated by Luke, where she attempted to heal feelings of guilt, shame and sadness related to those difficult years.

Her ayahuasca healing experiences, while including family topics, also had an impact on her perception of her job at a large technology firm. She described her company as fast-paced, competitive and challenging. Her goal was to increase her salary and advance her career by doing good work and getting noticed by senior colleagues. This required social tact, which ayahuasca assisted her in cultivating.

In one vision, she saw dozens of red lanterns floating up to the sky, each with a face of someone she loved or someone she despised, including her colleagues. The vision taught her to ‘let go of other people’s opinions easier.’ She explained:

After I cried for two or three hours [over my father’s death], I then puked a little bit. I was working on my own journey … When I saw the lanterns, I thought, it’s not their hope to make me sad, but I choose to be sad. It’s all on me. So, as the lanterns floated away, I was able to let some of my frustration and anger or unsatisfied feelings go with those people. Some of those people are in my company, working with me every day, or some are friends I sometimes see during the weekend … People who don’t believe in me, I now don’t see them as a threat blocking me from progressing in my company, and I don’t let their opinion bother me as much. The ayahuasca helped me feel it’s not personal anymore. I realised their advice is not always compatible with my expertise and development.

By closing the gap between inner and outer selves through insightful visions and releasing ‘negative energies’ from her body, Ting Ting felt relief from trauma and sensed an improvement in her management techniques at work.

‘What I learned from my father’s death,’ she explained, ‘is that you will not feel shame if you try your best to take care of someone or do something good.’ Reflecting on her ayahuasca sessions, she added: ‘After releasing the pain from my body, I became more comfortable with myself. My colleagues appeared more open to my ideas because I can manage my body language and expectations better now.’

He described the retreat bonding activities as being ‘like a good job interview’

In parallel, the ayahuasca practice of Wang, another of Luke’s clients, reveals the practical and quotidian dimensions of ayahuasca’s wonders. Wang is a Chinese American who spent his early years in California before moving to China after college, where he studied business management. Shortly after his studies, he began working as a manager for a Chinese company and started to frequent an ayahuasca retreat facilitated by Luke. Here, Wang sought personal and professional development, including help to address the anger he felt at home and in the workplace.

He had become increasingly stressed as an executive manager at a restaurant franchise. The business was excelling, partly due to his management efforts, but he was finding it difficult to cope with the new challenges and responsibility that came with opening more outlets. Business language and thinking permeated his approach to ayahuasca. He described the retreat bonding activities as being ‘like a good job interview’, similar to the way that a hiring committee might take a potential employee out of the office and into a park, where the group can ‘network together’ and ‘informally exchange’. Wang kept attending ayahuasca retreats because they provided him with a lasting sense of calm and peace, which he said helped him be more tender and perceptive as a father and husband, and more successful as a manager and business coach.

The beginning of the ayahuasca sessions with Luke were usually mentally challenging, disorienting and otherworldly, but eventually Wang ‘reached a certain level’ or had a ‘new ego death’ and then the rest of the session involved graceful periods in which he explored worldly affairs. He narrated one such session to me, in which a violent and dreamlike experience gave way to a period of visionary grace directed at his workplace challenges. At the start, ‘I was just an observer,’ he said, ‘like an audience member, watching’:

I wasn’t scared. I wasn’t worried or anxious. Physically, I did feel sick. I was seeing the same thing if I opened or closed my eyes. It was violent. Small and large creatures were climbing the walls, kicking and punching each other, and flying around. There was blood and water in the air. Ancient symbols were glowing on the walls, and trees and plants were growing out of them. The sensation, the smells, it was very real. The ceiling I remember vividly. It was open to outer space, and there was no sun, but I could feel a warmth like the sun.

Then, shortly after vomiting, he achieved a state of visionary peace and ‘flow’ in which he felt confident to tackle challenges and ‘turn the positive energy into something applicable’. He realised his pride had been affecting his management skills in negative ways that made the business operate less efficiently. He was failing to address performance issues with key managers and HR staff. Rather than expecting compliance, he now aimed to manage with less pride and better listening. ‘I visualise some of my challenges [during the ayahuasca session] and think, OK, tomorrow morning I want to make this decision and I want to start rolling out this execution,’ he explained. ‘It’s very detailed and very clear.’ Wang described his visions as ‘strange’ and ‘entertaining’ but expressed a motivated wonder towards the worldly aspects of his other visions. His ayahuasca sessions involved a release of negative emotion followed by a unity of grace and reasoning, intuition and rationality, spirit and success. The stress of the workplace was discharged in visions that enabled a renewed spirit to permeate his workplace perceptions and decisions.

These Chinese examples would likely come as a surprise to many Euro-American ayahuasca enthusiasts. Professionals using the brew to help them work more effectively and efficiently in dense megacities may seem far removed from what takes place during ayahuasca drinking sessions in the Amazon rainforest. And yet, there remain similarities. The practical applications of the brew have long been observed in South America where specialists have used ayahuasca to help find lost objects, discover the plans of enemies, cleanse the body, improve hunting perception, perceive ecological patterns in astronomical changes, and inspire artistic creations, among other utilitarian activities.

Although the tradition has shapeshifted considerably, ayahuasca drinkers in China were doing something similar-but-different to those in Amazonia. The question is: was this shared quality a similar essence with different appearances, or a similar appearance with different essences?

Speaking broadly, the effects of ayahuasca span the mundane to the remarkable. It produces moments of calm meditation as well as encounters with seemingly impossible yet uncannily real persons – whether animal, plant or human-like – who can disseminate knowledge and information in awe-inspiring encounters. The brew can impose a strangeness and a sense of immense power, as drinkers become astonished by these otherwise-invisible presences animated with vitality and marvellous beauty.

This brings the mysterious intelligence of the brew into conversation with what we bring to the cup

Afterwards – like so many other experiences of awe – drinking ayahuasca defies easy description. The anthropologist Luis Eduardo Luna describes it like this:

Without a doubt, one of the questions that comes to mind when experiencing ayahuasca has to do with the origin of all this beauty, all these extraordinary patterns, cities, palaces, gardens, jewels and extraordinary beings. Where does it all come from? … Ayahuasca takes us to realms where normal rationality is irrelevant, and where we are submerged in worlds of wonder and awe.

In experiencing and cultivating wonder through ayahuasca, we learn not only to see the world anew but to grapple with complexities that elude straightforward understanding, including those that are specific to culture and context. This brings the mysterious intelligence of the brew into conversation with what we bring to the cup, including our backgrounds, orientations and intentions.

Ultimately, the real wonder, at least for me, lies in how ayahuasca may both affirm and transcend our differences. The brew’s transformative power is neither purely internal nor wholly universal. It is relational, contextual and cultural. In each session, participants can navigate not only their own psyche but also the moral webs, collective concerns and shared longings of society and everyday life.

Perhaps the takeaway is that ayahuasca visions reveal that our relational horizons of mind, body, society – even species – are more expansive than we imagine. By navigating this vastness, we can encounter the therapeutic and practical insights that wonder itself inspires.