We have taken our places. This evening’s performance, sold out months in advance, is about to begin. The programme, handwritten in a traditional script on a rolled parchment, tied with string, tells us to expect a prologue, two chapters and an epilogue, without interval. I’m nervous with anticipation but I’m somewhat embarrassed to admit that it’s not because I am waiting for the curtain to rise on a Wagner opera or a Shakespeare play. I’m actually waiting for my dinner.

This is no ordinary meal, however. It’s the 19-course tasting menu at one of the world’s best restaurants, Frantzén/Lindeberg in Stockholm. Ranked number 20 in Restaurant magazine’s influential annual survey, it earned two Michelin stars in its first two years and is almost certain to get a third. Food doesn’t get much, if any, better than this.

Yet there seems something wrong about the effort and expense that fine dining like this involves. And when the average bill is the stiffest in the Nordic region, around €350 (or £280) per head, that unease can turn to moral outrage. What on earth could justify spending so much money on what is ultimately just fuel for humans, especially in a world where almost one billion people still go hungry every day?

Answering these questions was the main reason I was at the table at all. I was writing a book on food and philosophy and felt I needed to experience some of the extremes of food luxury. Of course, I also love eating, so it was a wonderful excuse. But I really don’t think I could have justified the reservation without some rationale other than pure pleasure. After all, this was going to be the most expensive three hours of my life.

Earlier, I had interviewed the head chef Björn Frantzén and he had played down expectations. He told me that he likes eating the sausages sold at football matches. Also that ‘I know there’s so many things wrong with it, but I think McDonald’s is nice’. And that ‘At the end of the day, let’s not forget, it’s a restaurant, you go to a restaurant because normally you’re hungry and it’s just food.’ As it turned out, he could not have been more wrong. This is not just food, and hunger is not the reason to eat it.

Take, for instance, the bone-marrow with caviar and smoked parsley. Delicious but, for all that, you might say it’s just an ephemeral experience. The obvious rejoinder is that of course it’s ephemeral: all experiences are; life itself is. The difference is that unlike, say, opera, when you are eating food you can never forget that fact. Certain aesthetic experiences of high art create a sense of transcendence, a feeling that you are somehow transported beyond the merely mortal realm to taste something of the divine. Indeed, that is precisely why some people believe art is so important.

I would argue the other way. The problem with art is that it can fool us into forgetting that we are mortal, flesh-and-blood creatures. The culinary arts, on the other hand, remind us that we are creatures of bone and guts, even as they delight us with creations no other animal could ever produce. Fine food is about the aesthetic of the immanent, not the transcendent. A mouthful of Frantzén’s diver scallops, truffle purée and bouillons transports you to heaven while never letting you forget it is a perishable place on Earth. Through experiences like these you come to know the potential intensity of being alive, what it means, as Thoreau recommended, to suck out all the marrow of life.

So yes, eating is ephemeral, but some experiences are so extraordinary they are worth it for their own sakes. Life is not just about such peak moments but it is very much enriched by them. ‘Mere experiences’ can also provide a kind of first-hand knowledge of the heights to which skill, flair and determination can take us. Perhaps it doesn’t matter which of the myriad forms of human excellence we most enjoy. Frantzén actually started out as a professional footballer for the top Swedish club, AIK Stockholm, before injury ended his career at the age of 20. I wondered whether he agreed that excellence is the thing that matters, not its particular vessel. He nodded in agreement, saying, ‘It happened to be cooking now, it could have been anything.’

Nor should it be seriously doubted that the very best chefs really do reach extraordinary heights, requiring rare skill, hard work and obsessive perfectionism. Take their dish of peas and beans, cream cheese of goat’s milk and mint. On the plate, it looks extremely simple, and in principle it is no more than the right ingredients put together in the right way. So why does this have a depth of flavour more usually associated with fine wine, along with an extraordinary ‘finish’: the taste that lingers in your mouth after you have swallowed, quite different from the one when you were chewing? Likewise, what explains how Satio tempestas, a small salad of 40 different ingredients, is delicious in a way that, from its description, is literally unimaginable?

The answer is that Frantzén has a rare depth of understanding of and sensitivity to ingredients. The restaurant has two gardens of its own and they harvest what Frantzén says is ‘peaking, when they are best in season, and that’s sometimes just a matter of a couple of days’. Hence the menu changes almost every day, as Frantzén adapts to create the perfect combinations of perfect ingredients.

And it’s not just about the combinations on the plates, but between them. ‘When you’re having a tasting menu, it’s a lot about the rhythm, and the speed you’re serving things,’ says Frantzén. So the frozen lemon verbena, for instance, is one of the simplest dishes on the menu, but it’s in exactly the right place at the right time.

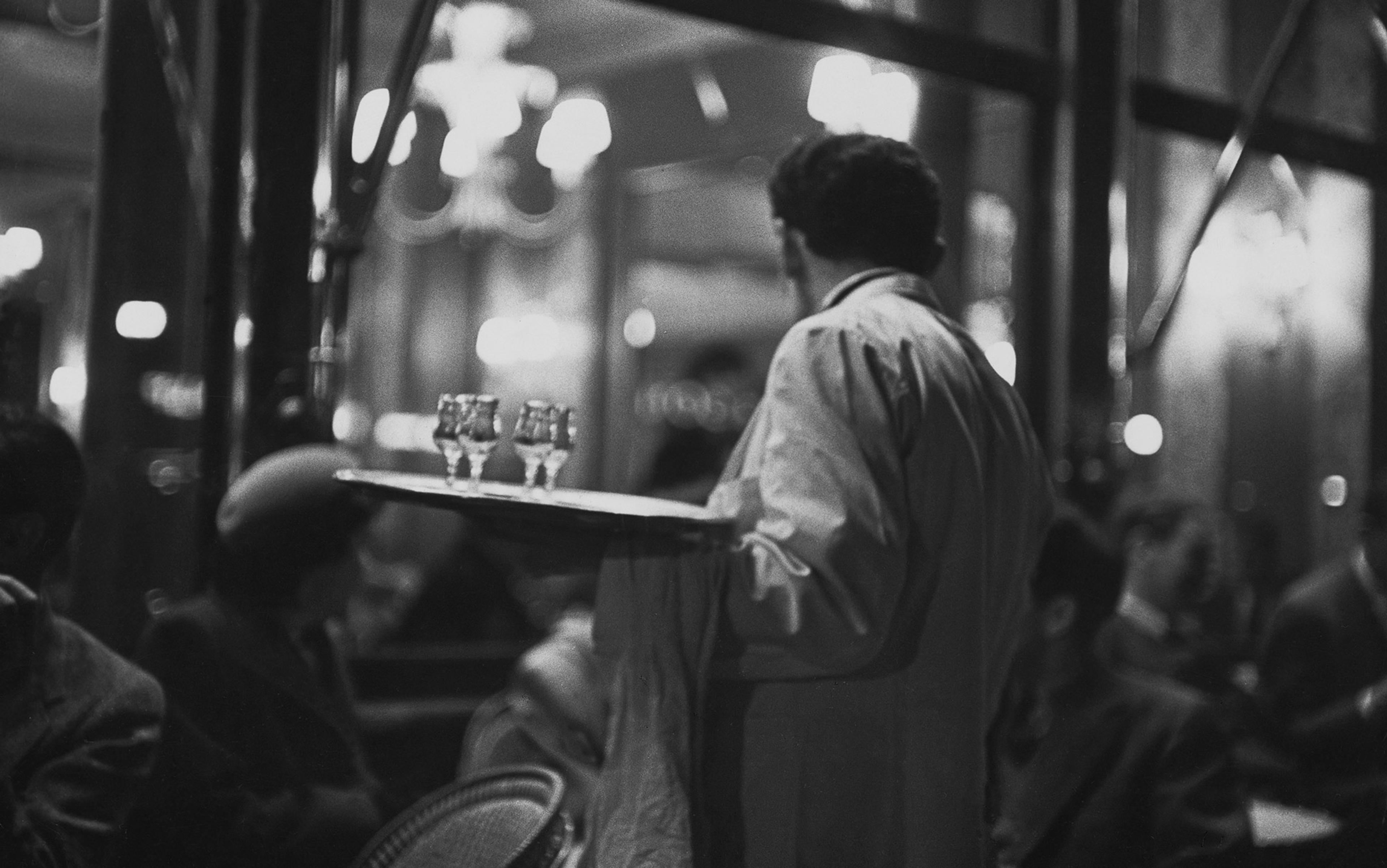

A meal like this is not just about delicious food. Frantzén says it sounds pretentious, but ‘it’s like going to the theatre … more than just what’s on the plate, it’s a lot of other things: storytelling, ingredients, where they’re coming from, how you present it, the look and feel of the restaurant’.

Our evening was full of theatre. As soon as we took our seats we saw a glass-topped wooden box on our table containing a small baguette-shaped piece of dough, proving. It was then taken away and baked over an open fire and brought back with some buttermilk, churned in front of us. At one point the maître d’ Jon Lacotte brought a piece of raw veal to our table and blow-torched it through a piece of coal. It was then taken away to return later as a ‘tartare’, with tallow from an 11-year-old milk cow, smoked eel and black roe.

This is not the cheap theatricality of banging plates or a flamboyant chef tossing pasta. Like a good play, you see only the action that is relevant to the plot, and that moves it forward to a satisfying resolution. So the freshest, most delicious bread and butter I’ve ever eaten, the very definition of simplicity, takes its rightful place alongside the most elaborate creations, because behind both is an incredible amount of care and effort to get it exactly right.

Still, there is the nagging question of cost. How could anyone possibly justify the bill? There is at least a financial logic to it. Ingredients such as the top-grade oyster, which came with frozen rhubarb, cream and juniper, cost a fortune. Frantzén’s business partner, the pastry chef Daniel Lindeberg, told me that 40 per cent of the bill is the cost of the ingredients alone. The rest is time. One dish we were served was whole turbot, which was baked for four hours at 55°C (130°F), with white asparagus baked for three hours with pine, lemongrass and mint. It takes longer to prepare a single ingredient of a single dish than it does for us to eat the whole meal. And it takes eight people in the kitchen, and about the same again outside it, to serve a total of 25 guests for dinner. Since I visited, that proportion has been ratcheted up again, with more kitchen space and less eating room: 11 chefs to 16 guests. Like an opera that requires an orchestra, a chorus and the world’s best solo voices, it’s this expensive because it costs this much to produce.

You have to be obsessive to push your cooking to such limits of originality and ingenuity, always at the edge, looking to create ‘the perfect restaurant, the perfect service, the perfect plate, the perfect menu’. To pursue excellence so doggedly, the restaurant has to come first, certainly above creaming off profit. ‘Let’s say the average spend here is, to make it easy, €350,’ says Frantzén. ‘It costs us €349 to sell for €350. Everything goes back to the customer. Everything. Our margin is almost zero.’

The extraordinary should not be allowed to become ordinary, no matter how good it is

Even if the economics justify the expense there is still, of course, a great deal of conspicuous consumption in high-end dining: showing off, being seen, being served by the servile and paying over the odds to do so. But the same is certainly true of opera. Any expensive art is going to attract a mixture of the true connoisseur and the conning poseur. However, this kind of restaurant is not just for show. You can’t get away with serving inferior food on silver platters as you might once have done. Frantzén and Lindeberg define the mood of the restaurant as ‘casual elegance’: focused on the cooking rather than the prestige the customer can glean from being seen there. This is progressive, not decadent.

The meal I had was without doubt the most incredible eating experience of my life. So many dishes were outstanding that there came a point at which the very word was meaningless. How can more things stand out than not? Perhaps that’s why, for all the wonder of the evening, it really would be wrong to do this kind of thing too often. The extraordinary should not be allowed to become ordinary, no matter how good it is.

There is also an inherent risk in splashing out at a really expensive restaurant, one that worried me when I bit into the very first dish of the evening, beef with lichens and ash. It was pretty tasty, but nothing amazing. Taste is so personal that you could save up for what is supposed to be one of the great gastronomic experiences in the world and be left cold. But again, the same can be true of great art, which you can admire without loving. As Frantzén said, at even the best restaurant ‘I might not like everything. I can leave and say, “It’s not actually my cup of tea, but they’re fucking great.”’

So as the bill arrived and, along with it, a wax-sealed brown envelope containing a typewritten copy of the menu with a list of the wines we have drunk, two questions arose. Could I justify the cost? And was it worth it? Despite the case I’ve made, I’m not sure I can confidently answer the first in the affirmative. But to the second, my heart and head both scream yes. It’s a contradiction some will find easier to digest than others.