I was in seventh grade in 1993 when Marie C Wilson and Gloria Steinem launched the Ms Foundation’s Take Our Daughters to Work Day, intending to show us young women that a big, wide world existed beyond our gender and our bodies. For me, it did just that, although it also seeded a lifetime obsession with bodies in a different sense. For while many of my classmates were sitting with a parent in a tidy office, I spent that inaugural daughter-at-work day in an autopsy room watching my father, a pathologist and former county coroner, dissect a dead man.

That man was a grizzled old farmer and he was delivered to the basement for autopsy at my dad’s hospital dressed in a long-sleeved shirt and denim overalls, a detail I remember clearly but that seems odd when I think about it now. I called my dad a few weeks ago to ask why the farmer wore overalls to his autopsy, and why there was an autopsy at all, which also seems unusual today. Dad doesn’t remember the case, one of so many over the years, but said there was likely no witness to the farmer’s death, in which case his doctor might have requested an autopsy to exclude an accident, suicide, or homicide. As for the clothes? That happens sometimes. People do, after all, often die while dressed. In our phone call I learned, too, that Dad doesn’t even remember taking me into the autopsy room. ‘I did that?’ he asked, laughing, incredulous. ‘An autopsy? Really?’

For me, the memory is clear. I remember that the farmer was the first dead body I’d seen. I remember standing at the edge of a cold room in oversized scrubs rolled up at the ankles and watching my dad, similarly dressed, struggle with the legs of the man’s overalls. I remember thinking that dead bodies don’t bend. I can see the farmer’s generous potbelly smiling at the ceiling after my dad finally stripped the clothes from him and laid him out, fully naked, on a metal gurney. I remember watching my dad as he wheeled the gurney to the centre of the room and transferred the man to an autopsy table, positioned under a bright light and over a drain. I can hear my dad dictating each step to a tape recorder in a business-like tone and, although I can’t make out the words, I remember that they seemed to be in a foreign language. I remember the long, Y-shaped incision the scalpel made on the man’s torso. I especially remember watching my dad cleave through the outer edges of the man’s ribs with an electric Stryker saw and then lift off his chest like the lid of a box. I also remember thinking: is that really my dad?

At the end of the autopsy, Dad rooted around the farmer’s still heart. Then he presented me with two grisly lumps in his gloved hands while earnestly explaining the difference between them. One was a tiny pre-mortem blood clot and the other a larger, post-mortem blood clot. In the former, the blood cells are mixed and the mass is uniform because the blockage formed when the blood still circulated. In the latter, the blood cells separate into distinct layers of yellow and red. If Dad found more of these pre-mortem clots and if the microscope confirmed what they were, we’d know that the farmer had died of a heart attack.

I don’t remember feeling scared or uncomfortable, but rather in awe at the scene in front of me. At the work my dad did. At the things that can happen to your body once you’re gone. And for the first time, it hit me that, after I die, part of me will remain.

Some of my strongest childhood memories involve gathering around the dinner table with my family and listening to stories of death. Of course this sounds morbid, but we were just doing what many families do over a shared meal, which is to talk about the kind of day each of us had. And for my dad, the day usually involved the dying or the dead.

The stories weren’t always about autopsies. Sometimes, Dad told us about receiving a hunk from a mysterious growth that a surgeon had cut from a patient, who still lay open on an operating table down the hall. Dad would quick-freeze the piece of tissue and slice it into thin cross-sections with something like a deli slicer. Then, he would put the translucent shavings on a slide, stain them purple and pink, and look at them under a microscope for the deadly harbinger of cancer. When I was young, the name for this process — frozen section — made me think of grocery stores.

Sometimes, the frozen section helped save the life of the person on the operating table: the doctors caught the cancer early, before it had spread, and removed the growth there and then. In others, the procedures came too late. These, Dad told with a heavy voice.

Other tales were about identifying a particularly rare disorder. Here, Dad described digging through medical literature and textbooks and then comparing one image of purple-pink-stained cellular architecture to another to look for distinctive patterns.

My favourites, however, were the coroner stories, which were ghastly in a way that absorbed me as a child but that carry a different weight now in my adult mind (although, with today’s ubiquitous forensics television shows, I suppose solving unusual deaths fascinates us all). There was the one about the woman who shot her husband through the common carotid artery with a .357 Magnum, and the cautionary tale of the toddler who was crushed by the wheel of a school bus. That one still haunts me.

What I learned is this. To study the human body, nothing but a real one comes close

Then there is the story I’d beg for whenever I had friends at the house for dinner or a sleepover, which now makes me wonder why they ever came back. It begins with Dad stepping out of his car in the wide rural farmland of north-east Kansas to the staccato retorts of gunshots. Startled, he turned to the sheriff waiting to take him to a death scene, who drawled: ‘Don’t worry. They’re just gettin’ the last of the dogs.’

My dad was there to examine the limited remains of an elderly couple who had died and to piece together what had happened to them. Based on the eviction notice in the mailbox and the half-packed car, he deduced that the couple had been moving out of their dirt-floored shack. The woman’s medical history suggested she couldn’t walk; her remains in the bed indicated she’d died there. Perhaps she had been waiting for her husband to help her to the car after he’d finished loading it. Instead, he’d had a heart attack in the thick summer heat. The hypothesis made sense, anyway, from the man’s own medical records and the suitcases that sat in the dusty drive between the shack and the open car. Unable to walk or to yell for the nearest neighbour miles down the road, the woman slowly wasted away.

All that was left of the man was a piece of his occipital bone, from the lower part of his skull. What happened to the rest of him? Through interviews, county deputies learned that the couple had befriended a pack of feral dogs. The dogs were accustomed to being fed scraps from the shack. When the couple died, the hungry dogs turned on them.

It’s a horrible, sad story, yes. However, to my child’s mind at sleepovers, it was like a ghost story. But better.

Twenty years after my Take Our Daughters to Work Day experience, although I am still young and in good health, I’ve been reliving that autopsy scene as I contemplate what will happen to my body when I die. We humans have a unique faculty for existential navel-gazing; to understand the difference between is and was, between life and death. We can trace the path of a life to its logical conclusion: no matter the precautions, the detours, or the scenic routes, some day it will end. And once I get past the paralysing, trapped-animal fear that accompanies such thoughts, I start to wonder what will happen next. What path might my body take once whatever makes me ‘Me’ is gone?

I don’t mean this in a spiritual way. Many people come to accept death through the promise that they will live on in an afterlife or through reincarnation, but these aren’t my beliefs. Nor do I share the view of the gerontologist who wants to cure ageing altogether, or the futurist who is waiting patiently for the singularity; to me, both seem like just another way to avoid accepting death, under the veil of science rather than religion. What I’m talking about is what will happen to my shell, my physical remains, when I die. I’d like to have control over where my body will go and what it might do, even in death. I find comfort in knowing I have a say.

The thought of being immediately sealed in an expensive box or cremated does not appeal. I understand that such longstanding cultural traditions console the people who remain behind, but to me it seems that my body would be wasted in either case. Before it reaches its final resting place, I want my body to be useful.

To do this, I need to think of a way for my death to make life better for the living. One option is to donate usable organs to someone who needs them: corneas for the blind, skin grafts for the badly burned, or a variety of other organs, from the heart to the kidneys to the lungs, for the diseased. I’ve already been an organ donor for as long as I can remember; it’s printed on my driver’s licence under a red cartoon heart. But lately, when I’ve thought about dying, I’ve wondered if, for me, this is the most meaningful donation. Coincidentally, my driver’s licence is due for renewal at the end of this year.

I recently wrote a short article on the different ways in which whole-body donations are used in research and in medical education. As I interviewed the scientists and doctors involved in this work, I realised that my questions about the anonymous cadavers they use were not just for the purpose of writing my article. The subtext was that I was asking how my body would be used, should I decide to leave it as an anatomical gift.

I’m told by those who have experienced it that the relationship between medical students and their first cadaver is a special one

What I learned is this. To study the human body, nothing but a real one comes close. There are usable proxies — computer models and crash-test dummies, for example. But neither replaces the real thing and, in fact, both are built and tuned with data collected from cadavers. Without input from real bodies, with their real anatomical complexity, neither substitute would exist.

There are never enough whole-body donations. In any given year, researchers make do with what they’ve been given, but they could always use more. There are obstacles: a person or their surviving family must give consent, different legal frameworks exist from one country or region to the next, and some bodies aren’t suitable for all areas of research. Not every donation programme is what it seems, either, and the best way to ensure that my body goes to research is to donate through a state anatomical board or a medical school.

Many areas of research require cadavers. Scientists who study the biomechanics of injury, for example, want to understand how the human body gets hurt so that they can help to prevent it. They craft controlled tests to understand the impacts a cadaver can withstand. Then, after translating these measurements to a model or a dummy, they test and perfect the protective gear that keeps us safe.

My body, I learned, could help improve safety belts in a car or seats in a train. My brain might help designers make helmets that mitigate the traumatic brain injuries an American football player sustains in a rough tackle, or a soldier gets from the shockwave of a bomb blast. When the research is done, if my family wishes, they can have my cremated remains (in which case, I wouldn’t mind if my ashes are spread somewhere I once loved). If not, I might be honoured alongside other unclaimed donors by a plaque, a tree, or a solemn annual ceremony.

Forensic scientists, too, use cadavers in their work. A handful of universities take donated bodies and plant them in the ground or place them in a secluded wood. Then the scientists map out the time it takes for the blowflies, dermestid beetles, and other scavengers to render the bodies to bones. This, I suppose, is a different sort of reincarnation — to become part of the ecosystem of a field or forest floor. It might seem a grim end, but the data can help forensic researchers identify the time when a person died and what injuries they might have suffered, which in turn helps law enforcement officers to solve murders.

If I were to choose this route, my body might eventually be used to recreate a specific crime scene — hanged in the forest, or stuffed in a car trunk — which could help a coroner solve a case, or a cop bring a killer to justice, just as my dad once helped unravel deadly crimes. Maybe this would bring some solace to a grieving family. Afterward, my skeleton might rest in box in a forensics collection, occasionally living on in the form of research on the ageing of bones.

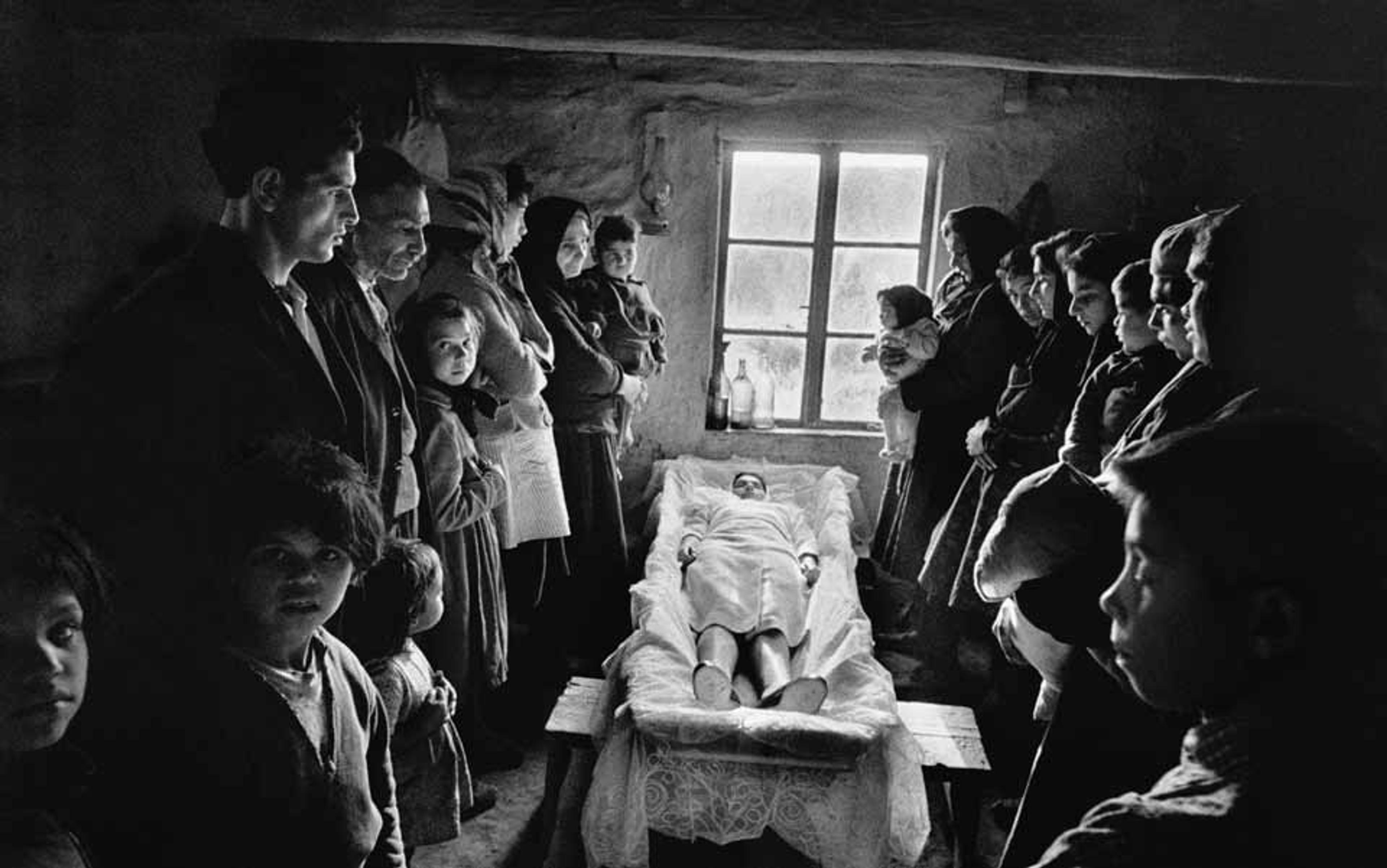

These are all worthy legacies, but there is one more option for whole-body donation, a longstanding tradition in medical training, that feels a better fit for me. Every first-year medical student takes a gross anatomy course in which they dissect a human cadaver. This is their first patient. It might be the first dead body they have ever seen or touched. When they enter the gross anatomy room, they might see two- or three-dozen different bodies, each a unique example of the dizzying array of human size and shape.

I’m told by those who have experienced it that the relationship between medical students and their first cadaver is a special one. The cadaver provides knowledge the student wouldn’t have otherwise; the student is awed and thankful for the gift. One physician I interviewed told me: ‘You learn the facts, but you come out of the process with appreciation, with a reverence for this majestic structure in front of you. And you appreciate a human being in a very different way.’

In this scenario, if I were to choose it, my body might teach a future doctor the physical landmarks for inserting a spinal tap, or for ruling out appendicitis. A surgeon might learn to dissect the delicate nerves in my hands. Or, perhaps, a pathologist might realise the difference between a pre-mortem and post-mortem blood clot.

It’s a heavy decision, to choose where you’ll go when you die, and a deeply personal one. Many people don’t want to bother, and some don’t even get a say. For me, I choose an active role, and I’m lucky to have that opportunity. I haven’t made a final decision yet, but a medical school body donation application form is saved on my computer desktop. Maybe, by December 31 of this year — the day my driver’s licence expires, as well as my birthday — I will fill out this application and drop it in the mail.