There’s no emotion we ought to think harder and more clearly about than anger. Anger greets most of us every day – in our personal relationships, in the workplace, on the highway, on airline trips – and, often, in our political lives as well. Anger is both poisonous and popular. Even when people acknowledge its destructive tendencies, they still so often cling to it, seeing it as a strong emotion, connected to self-respect and manliness (or, for women, to the vindication of equality). If you react to insults and wrongs without anger you’ll be seen as spineless and downtrodden. When people wrong you, says conventional wisdom, you should use justified rage to put them in their place, exact a penalty. We could call this football politics, but we’d have to acknowledge right away that athletes, whatever their rhetoric, have to be disciplined people who know how to transcend anger in pursuit of a team goal.

If we think closely about anger, we can begin to see why it is a stupid way to run one’s life. A good place to begin is Aristotle’s definition: not perfect, but useful, and a starting point for a long Western tradition of reflection. Aristotle says that anger is a response to a significant damage to something or someone one cares about, and a damage that the angry person believes to have been wrongfully inflicted. He adds that although anger is painful, it also contains within itself a hope for payback. So: significant damage, pertaining to one’s own values or circle of cares, and wrongfulness. All this seems both true and uncontroversial. More controversial, perhaps, is his idea (in which, however, all Western philosophers who write about anger concur) that the angry person wants some type of payback, and that this is a conceptual part of what anger is. In other words, if you don’t want some type of payback, your emotion is something else (grief, perhaps), but not really anger.

Is this really right? I think so. We should understand that the wish for payback can be a very subtle wish: the angry person doesn’t need to wish to take revenge herself. She may simply want the law to do so; or even some type of divine justice. Or, she may more subtly simply want the wrongdoer’s life to go badly in future, hoping, for example, that the second marriage of her betraying spouse turns out really badly. I think if we understand the wish in this broad way, Aristotle is right: anger does contain a sort of strike-back tendency. Contemporary psychologists who study anger empirically agree with Aristotle in seeing this double movement in it, from pain to hope.

The central puzzle is this: the payback idea does not make sense. Whatever the wrongful act was – a murder, a rape, a betrayal – inflicting pain on the wrongdoer does not help restore the thing that was lost. We think about payback all the time, and it is a deeply human tendency to think that proportionality between punishment and offence somehow makes good the offence. Only it doesn’t. Let’s say my friend has been raped. I urgently want the offender to be arrested, convicted, and punished. But really, what good will that do? Looking to the future, I might want many things: to restore my friend’s life, to prevent and deter future rapes. But harsh treatment of this particular wrongdoer might or might not achieve the latter goal. It’s an empirical matter. And usually people do not treat it as an empirical matter: they are in the grip of an idea of cosmic fitness that makes them think that blood for blood, pain for pain is the right way to go. The payback idea is deeply human, but fatally flawed as a way of making sense of the world.

There is one, and I think only one, situation in which the payback idea does make sense. That is when I see the wrong as entirely and only what Aristotle calls a ‘down-ranking’: a personal humiliation, seen as entirely about relative status. If the problem is not the injustice itself, but the way it has affected my ranking in the social hierarchy, then I really can achieve something by humiliating the wrongdoer: by putting him relatively lower, I put myself relatively higher, and if status is all I care about, I don’t need to worry that the real wellbeing problems created by the wrongful act have not been solved.

A wronged person who is really angry, seeking to strike back, soon arrives, I claim, at a fork in the road. Three paths lie before her. Path one: she goes down the path of status-focus, seeing the event as all about her and her rank. In this case her payback project makes sense, but her normative focus is self-centred and objectionably narrow. Path two: she focuses on the original offence (rape, murder, etc), and seeks payback, imagining that the offender’s suffering would actually make things better. In this case, her normative focus is on the right things, but her thinking doesn’t make sense. Path three: if she is rational, after exploring and rejecting these two roads, she will notice that a third path is open to her, which is the best of all: she can turn to the future and focus on doing whatever would make sense, in the situation, and be really helpful. This may well include the punishment of the wrongdoer, but in a spirit that is deterrent rather than retaliatory.

Most people begin with everyday anger: they really do want the offender to suffer

So, to put my radical claim succinctly: when anger makes sense (because focused on status), its retaliatory tendency is normatively problematic, because a single-minded focus on status impedes the pursuit of intrinsic goods. When it is normatively reasonable (because focused on the important human goods that have been damaged), its retaliatory tendency doesn’t make sense, and it is problematic for that reason. Let’s call this change of focus the Transition. We need the Transition badly in our personal and our political lives, dominated as they all too frequently are by payback and status-focus.

Sometimes a person may have an emotion that embodies the Transition already. Its entire content is: ‘How outrageous! This should not happen again.’ We may call this emotion Transition-Anger, and that emotion does not have the problems of garden-variety anger. But most people begin with everyday anger: they really do want the offender to suffer. So the Transition requires moral, and often political, effort. It requires forward-looking rationality, and a spirit of generosity and cooperation.

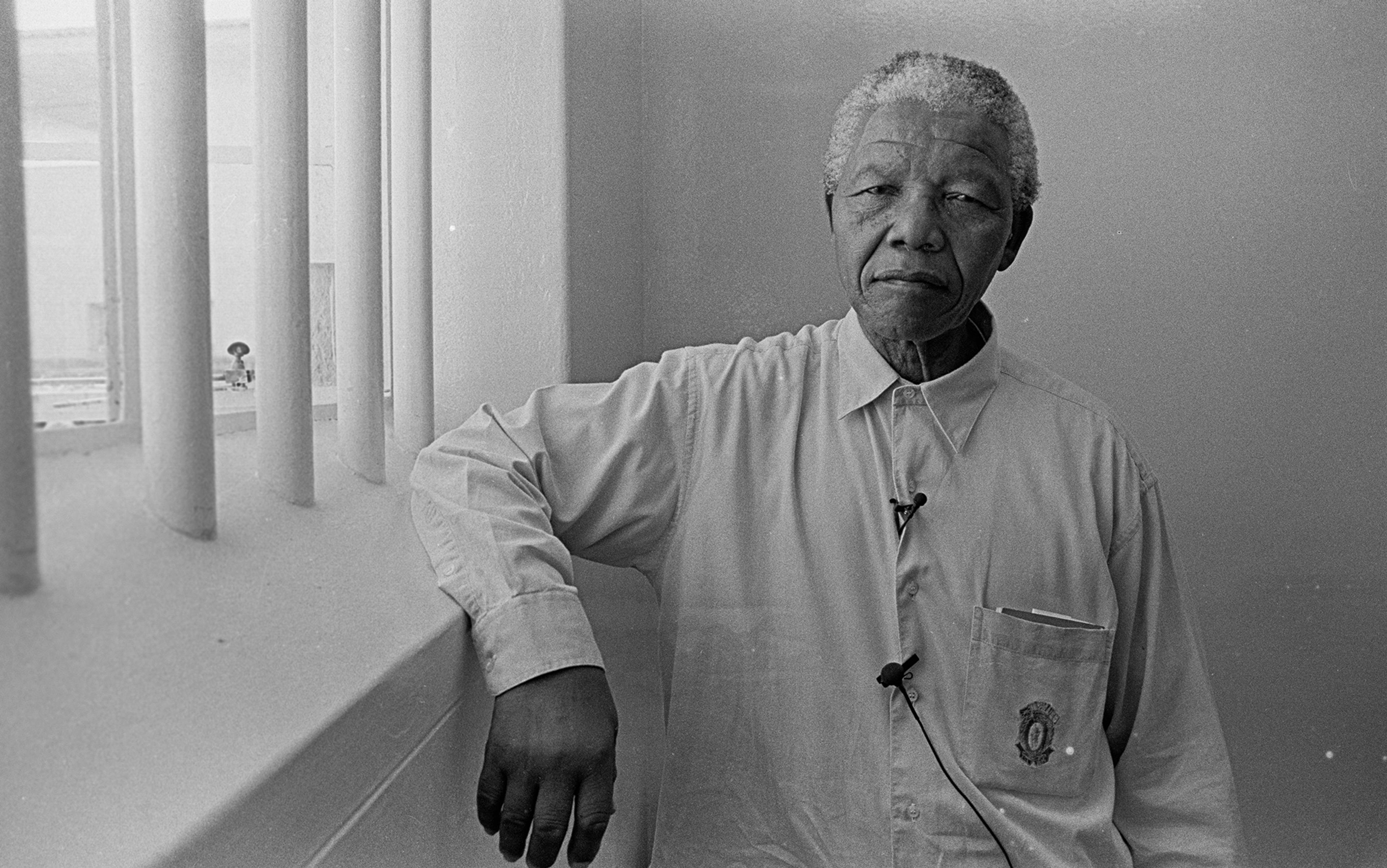

The struggle against anger often requires lonely self-examination. Whether the anger in question is personal, or work-related, or political, it requires exacting effort against one’s own habits and prevalent cultural forces. Many great leaders have understood this struggle, but none more deeply than Nelson Mandela. He often said that he knew anger well, and that he had to struggle against the demand for payback in his own personality. He reported that during his 27 years of imprisonment he had to practise a disciplined type of meditation to keep his personality moving forward and avoiding the anger trap. It now seems clear that the prisoners on Robben Island had smuggled in a copy of Meditations by the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, to give them a model of patient effort against the corrosions of anger.

But Mandela was determined to win the struggle. He wanted a successful nation, even then, and he knew that there could be no successful nation when two groups were held apart by suspicion, resentment, and the desire to make the other side pay for the wrongs they had done. Even though those wrongs were terrible, cooperation was necessary for nationhood. So he did things, in that foul prison, that his fellow prisoners thought perverse. He learned Afrikaans. He studied the culture and thinking of the oppressors. He practised cooperation by forming friendships with his jailers. Generosity and friendliness were not justified by past deeds; but they were necessary for future progress.

Mandela used to tell people a little parable. Imagine that the sun and the wind are contending to see who can get a traveller to take off his blanket. The wind blows hard, aggressively. But the traveller only pulls the blanket tighter around him. Then the sun starts to shine, first gently, and then more intensely. The traveller relaxes his blanket, and eventually he takes it off. So that, he said, is how a leader has to operate: forget about the strike-back mentality, and forge a future of warmth and partnership.

Mandela was realistic. One would never have found him proposing, as did Gandhi, to convert Hitler by charm. And of course he had been willing to use violence strategically, when non-violence failed. Non-anger does not entail non-violence (although Gandhi thought it did). But he understood nationhood and the spirit that a new nation requires. Still, behind the strategic resort to violence was always a view of people that was Transitional, focused not on payback but on the creation of a shared future in the wake of outrageous and terrible deeds.

Again and again, as the African National Congress (ANC) began to win the struggle, its members wanted payback. Of course they did, since they had suffered egregious wrongs. Mandela would have none of it. When the ANC voted to replace the old Afrikaner national anthem with the anthem of the freedom movement, he persuaded them to adopt, instead, the anthem that is now official, which includes the freedom anthem (using three African languages), a verse of the Afrikaner hymn, and a concluding section in English. When the ANC wanted to decertify the rugby team as a national team, correctly understanding the sport’s long connection to racism, Mandela, famously, went in the other direction, backing the rugby team to a World Cup victory and, through friendship, getting the white players to teach the sport to young black children. To the charge that he was too willing to see the good in people, he responded: ‘Your duty is to work with human beings as human beings, not because you think they are angels.’

Mandela asks only, how shall I produce cooperation and friendship?

And Mandela rejected not only the false lure of payback, but also the poison of status-obsession. He never saw himself as above menial tasks, and he never used status to humiliate. Just before his release, in a halfway house where he was still officially a prisoner, but had one of the warders as his own private cook, he had a fascinating discussion with this warder about a very mundane matter: how the dishes would get done.

I took it upon myself to break the tension and a possible resentment on his part that he has to serve a prisoner by cooking and then washing dishes, and I offered to wash dishes and he refused … He says that this is his work. I said, ‘No, we must share it.’ Although he insisted, and he was genuine, but I forced him, literally forced him, to allow me to do the dishes, and we established a very good relationship … A really nice chap, Warder Swart, a very good friend of mine.

It would have been so easy to see the situation as one of status-inversion: the once-dominating Afrikaner is doing dishes for the once-despised ANC leader. It would also have been so easy to see it in terms of payback: the warder is getting a humiliation he deserves because of his complicity in oppression. Significantly, Mandela doesn’t go down either of these doomed paths, even briefly. He asks only, how shall I produce cooperation and friendship?

Mandela’s project was political; but it has implications for many parts of our lives: for friendship, marriage, child-rearing, being a good colleague, driving a car. And of course it also has implications for the way we think about what political success involves and what a successful nation is like. Whenever we are faced with pressing moral or political decisions, we should clear our heads, and spend some time conducting what Mandela (citing Marcus Aurelius) referred to as ‘Conversations with Myself’. When we do, I predict, the arguments proposed by anger will be clearly seen to be pathetic and weak, while the voice of generosity and forward-looking reason will be strong as well as beautiful.

Anger and Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity, and Justice (2016) by Martha C Nussbaum is out now through Oxford University Press.