The nightmare started with a piece of toast. As a patient at an eating-disorder treatment centre, Holly was required to finish everything on her plate or drink a high-calorie liquid supplement. Already uncomfortably full after eating everything else, she couldn’t finish the slice of toast. A nurse reminded her of the rule: toast or supplement. She tried to explain that it was only her fourth day in treatment and she had already eaten nearly twice what she had been eating at home. The nurse insisted. Finally, Holly admitted: ‘I can’t. I’m scared.’

But the facility didn’t see fear, it saw defiance. In her panic, Holly had pushed a nurse out of the way, which was written down as a physical assault on staff. So the treatment centre transported Holly to a locked psychiatric ward where she was held against her will for the next five days. She was restrained, drugged, and humiliated, all of which gave Holly flashbacks and nightmares. Only after stuffing herself full of food for two days straight to convince the hospital that she wasn’t a danger to herself or to others was she released.

‘Defiant or not, as a patient, I have the right to participate in my own care, and that was taken from me,’ she said.

In nearly two decades of treatment for depression and eating disorders, Holly has frequently been called defiant. She doesn’t hesitate to stand her ground and state her opinion, even if it makes people uncomfortable. Her shaved head and multiple piercings and tattoos add to her defiant image. Holly doesn’t deny that the word applies to her – after all, she tried to enlist the help of the American Civil Liberties Union in suing her high school on the grounds that their community service requirement violated the 14th Amendment. Her problem is that the only thing people can see is defiance.

‘All they see is a pain in the ass,’ she said.

Certainly, people undergoing psychiatric treatment can be challenging, for good reason: the medicine they are asked to take can make their brains feel foggy and flat, cause weight gain and even obesity, and have unpleasant side effects such as constipation, loss of sex drive and dry mouth. But whenever these patients object, they are labelled defiant, a stance that often reinforces the impression that they are irrational players, psychiatric cases worthy of removal from society.

The problem is compounded when physicians, and society at large, see rebelliousness in a psychiatric light, and then shift disease definitions to describe the rebelliousness – even in the absence of diagnosable psychiatric disease. Holly says that without her defiance, her tendency to say ‘Fuck you’ instead of ‘Thank you’, she wouldn’t have been shipped out to the psychiatric unit.

And when the defiant ones are locked up in prisons and hospitals, they are unable to force changes in the status quo – not only do they lack control over the treatment dispensed, they are also unable to express their change-making views on culture and the world. And what a loss: without people protesting police shootings of unarmed black men in Ferguson and Baltimore, racial violence will continue. Without sexual assault victims speaking out against how they were blamed for crimes committed against them, rape culture will go on. Defiance forces us to chip away at the cornerstones of our culture, but it’s all too easy to turn our discomfort into the defiant ones’ psychiatric disease.

Without defiance, the values of the Western world might not exist at all. Early Christians defied laws banning their new religion, worshipping in private and sometimes being killed for their beliefs. In Russia and Europe, serfs defied their masters. Slaves did the same in the United States, ultimately winning their freedom. Women’s right to vote, life-saving treatments for HIV infection, and marriage equality are all the result of defiant acts. Defiance is the Occupy Wall Street movement, protesting income inequality, and Black Lives Matter, bucking a system where law enforcement imprisons young black men at many times the rate of other groups.

Acts of defiance can be solitary or small. High-school students defy social norms by openly defining themselves as gay, bisexual or transgender. Office workers defy corporate culture by brightly decorating their cubicles. Fat-acceptance activists refuse to change their weight for the sake of appearance. Defiance defines the visual arts student Emma Sulkowicz, who carried her mattress around Columbia University in New York City in protest at how they handled her sexual assault.

Yet defiance is often pathologised, with psychiatrists sometimes leading the charge. It’s something Nancy Potter sees all the time. A Professor of Philosophy at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, Potter has spent the past few years researching how psychiatrists interpret and manage defiance in their patients. ‘Like all of us, psychiatrists carry stereotypes about who appears in front of them, and they tend to see those people as patients. As soon as that happens, they start looking for certain characteristics, such that they see a person’s resistance as defiance,’ Potter says.

The former Soviet Union wielded the insanity club, imprisoning dissidents in psychiatric units known as psikhushkas, removing them from society and discrediting their ideas. Mental illness was the only possible reason someone could oppose the best sociopolitical system humanity had ever invented, some contended. Those in the upper echelons of the Communist Party systematically used the diagnosis of ‘sluggish schizophrenia’ to lock away the opposition. By 1973, schizophrenia was far more prevalent in Moscow than nearly anywhere else on Earth, according to the World Health Organization. Not only did framing opposition as mental illness keep dangerous ideas about freedom and democracy from spreading through Soviet society, it also framed these concepts as little more than the ravings of madmen.

Although high-ranking Soviet psychiatrists received orders to imprison dissidents from the Communist party and the KGB, some of them genuinely believed in the idea of sluggish schizophrenia. Why would an otherwise normal person risk everything – home, career, family, life – to oppose the government, if not for genuine mental illness? The diagnosis also provided a convenient excuse for practicing psychiatrists to impose their own stance on communism through oppression of dissenters, notes Dutch human rights activist Robert van Voren. By the 1980s, van Voren and the International Association on the Political Use of Psychiatry estimate that thousands in the Soviet Union were wrongly institutionalized for schizophrenia and other trumped up mental illnesses, a number that excludes those who were hospitalized for shorter periods and then released.

Even as the Soviet Union dissolved in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the concept spread east to China, which has fallen under similar scrutiny for diagnosing reformers and opposition leaders with mental illness. In 1999, the Chinese government declared the religious movement Falun Gong, which uses ritual mental and physical exercises to bring spiritual growth, to be a cult. Following a wave of persecutions, the Chinese government imprisoned more than a thousand otherwise mentally healthy Falun Gong practitioners in mental hospitals around the country. Smuggled documents reveal that many of these individuals were tortured and abused; some died as a result.

In 2012, Chinese Human Rights Defenders, a Hong Kong-based human rights group, released a report called ‘The darkest corners: abuses of involuntary psychiatric commitment in China.’ They noted that ‘China’s involuntary commitment system is a black hole into which citizens can be “disappeared” for an indefinite period of time based on the existence or mere allegation of a psychosocial disability by family members, employers, police or other state authorities… Those who have the means – power and money – to either compel or pay psychiatric hospitals to detain individuals out of a desire to punish and silence them have been able to do so with impunity.’ Under this system, individuals have been ‘taken to psychiatric hospitals to punish them after they acted in ways that irked government officials, such as petitioning higher authorities or publishing articles criticizing the government.’

The tactic was seen in the United States as early as 1851, when the abolition movement began to gain traction in the north. Newspapers, books and pamphlets all raised awareness of the plight of African slaves in the South, and of slaves who were resisting captivity and fleeing towards freedom. That a slave would want to be free might seem like an obvious aspiration, but it conflicted with many slave owners’ insistence that blacks were better off enslaved.

The Southern physician Samuel Cartwright saw the yearning for freedom as a symptom of a supposed mental illness called drapetomania (from the Greek words for ‘runaway mania’). ‘It is unknown to our medical authorities, although its diagnostic symptom, the absconding from service, is well known to our planters and overseers,’ he wrote in 1851 in De Bow’s Review. ‘The cause… that induces the negro to run away from service, is as much a disease of the mind as any other species of mental alienation.’

In the same paper, Cartwright described a related psychiatric disease, dysaesthesia aethiopica, that he said was ‘the natural offspring of negro liberty – the liberty to be idle, to wallow in filth, and to indulge in improper food and drinks’. It’s easy to roll our eyes at such shoddy logic and obvious racism. But to many Southern whites, Cartwright’s explanations made perfect sense. They were used to justify both the murder of slaves and the recapture of runaways.

Eventually the Civil War ended slavery, but not the habit of seeing defiance as mental illness. Sitting in front a dusty box of century-old patient charts in a dimly lit reading room, the psychiatrist and sociologist Jonathan Metzl, now at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, found himself documenting one of the most powerful intersections of defiance and psychiatry in modern US medicine. From 1885 to 1976, the Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane was the centre of a tiny town in West Michigan that became home to some of the most marginalised and forgotten individuals. Over the 91 years of its operation, it diagnosed hundreds, even thousands, of individuals with schizophrenia. Metzl didn’t find this overly surprising.

the hallmarks of schizophrenia changed from tearfulness and confusion to delusion, hostility and aggression – or from white housewives in the suburbs to urban black men

As he dug more deeply into patient charts – many of which were ‘thicker than a New York City phone book’, filled with observations from physicians, nurses and orderlies – he found a much more interesting story. Up through the 1950s, schizophrenia was not an especially feared diagnosis at Ionia. It did not conjure up images of homeless men muttering to themselves on the street. Schizophrenia was largely a disease of white females, housewives who grew tired and weepy, attempted suicide or committed minor offences such as shoplifting or disturbing the peace. Metzl read chart notations such as ‘The patient wasn’t able to take care of her family as she should,’ or ‘This patient is not well adjusted and can’t do her housework,’ or even ‘She got confused and talked too loudly and embarrassed her husband.’

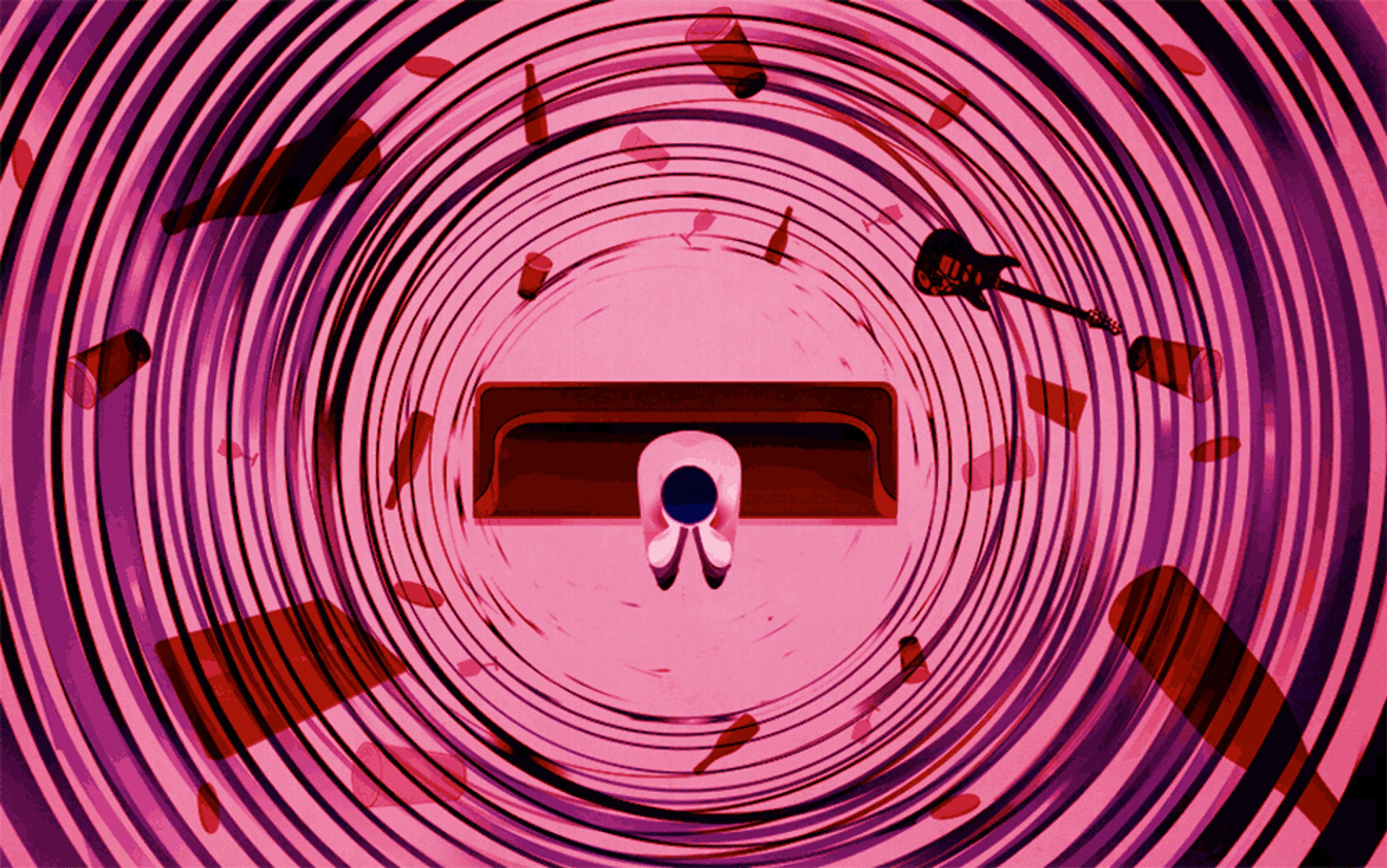

As the 1960s progressed, that started to change, reflected in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a book that outlines criteria for psychiatric diagnoses. The modifications were made just as the civil rights movement began picking up steam. All across the US, people joined protests and rallies for racial inequality. In Detroit, just 130 miles from Ionia, race riots swept through the city in 1967. When the second edition of the DSM appeared in 1968, psychiatrists had changed the hallmarks of schizophrenia from primarily mood symptoms such as tearfulness and confusion to signs of delusion, hostility and aggression – or from white housewives in the suburbs to urban black men.

‘The researchers probably thought that these changes were helping them be more scientific in the way they diagnosed schizophrenia, but when they were used in the clinic and in society, all of a sudden it turned out that the terminology was used to overdiagnose black men, especially those who were part of political protest movements,’ Metzl said.

At Ionia, Metzl found, the demographics began to shift. Instead of a mostly white prison population, new admissions were overwhelmingly African-American men. Metzl found the same diagnoses on their charts: schizophrenia, paranoid type. Metzl calls this ‘the protest psychosis’, in a book of the same name published in 2010. All of the men had been arrested for some type of crime, whether it was assaulting a police officer, larceny, homicide or property destruction. Some already had potential mental-health issues when they were arrested, whereas others did not become apparent until after the men were already jailed. Regardless, almost all received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Even as the Community Mental Health Act of 1963 shifted funding from state mental hospitals to community mental-health centres, discharging thousands of institutionalised individuals into the community, these black men remained at Ionia, held as a danger to society, often long after their criminal sentences were done. ‘Schizophrenia was a way for whites to pathologise what they defined as “crazy anger” in blacks. It became a potent metaphor in racial politics,’ Metzl said.

The DSM has been revised several times since 1968, and the language used to define schizophrenia has also been changed and clarified, but racial disparities remain. African-Americans are still three times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than whites, even after accounting for a person’s socioeconomic status at birth. Such disparities, Metzl believes, are an echo of the defiance of the 1960s.

This defiance often continued while the men were in Ionia. It’s no wonder, says the psychiatrist Richard Warner, Director of Colorado Recovery in Boulder, who died just before this article was published. ‘If you’re in a place that looks like a prison, you’re going to behave like a prisoner.’

Of course, not all psychiatric diagnoses are equally valid. Acts of defiance in the 1970s helped to get homosexuality removed from the DSM as a diagnosis (it had been included in both its first and second editions, published in 1952 and 1968, respectively).

‘These psychological theories were based on people who had come into treatment and were unhappy with their lives, as well as prison populations,’ said Jack Drescher, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice in New York City, and an expert on sexual and gender identity disorders.

The publication in 1957 of a study by the psychologist Evelyn Hooker at the University of California, Los Angeles showing that gay men in the community were just as well-adjusted as their heterosexual peers was one of the first major scientific challenges to the idea put forward by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) that homosexuality was an illness. Throughout the 1960s, the idea was increasingly challenged by gay and lesbian activists.

Why, if someone was innocent, would he run from the police and risk being shot?

But it was an act of defiance at the APA’s 1970 annual meeting that ultimately led to the removal of homosexuality in the DSM. At a session on the use of electroshock therapy to reduce homosexual attraction, gay activists stormed the room and called psychiatrists who used this method ‘torturers’. With Hooker’s work as ammunition, they told the psychiatrists at the meeting that homosexuality was not an illness and it was wrong to treat it as such. Although some walked out of the meeting, other psychiatrists stayed to listen. The next year, the APA convened meetings with gay activists and psychiatrists to discuss the topic. By 1973, in the next DSM revision, homosexuality was removed.

Recent riots in the US, in Ferguson and Baltimore in response to police killings of young black men, have likewise left some people confused. Why, they ask, would someone destroy their own neighbourhood? Why, if someone was innocent, would he run from the police and risk being shot? Isn’t all of this behaviour kind of, well, crazy?

But look at the social order – the racial, sexual and economic odds stacked against the protestors. Given the consequences, maybe you would have to be crazy to challenge the status quo. Defying the prevailing viewpoint that chronic poverty results from laziness, that women who were raped were just asking for it, and that African-Americans have nothing to fear from the police might seem insane to some.

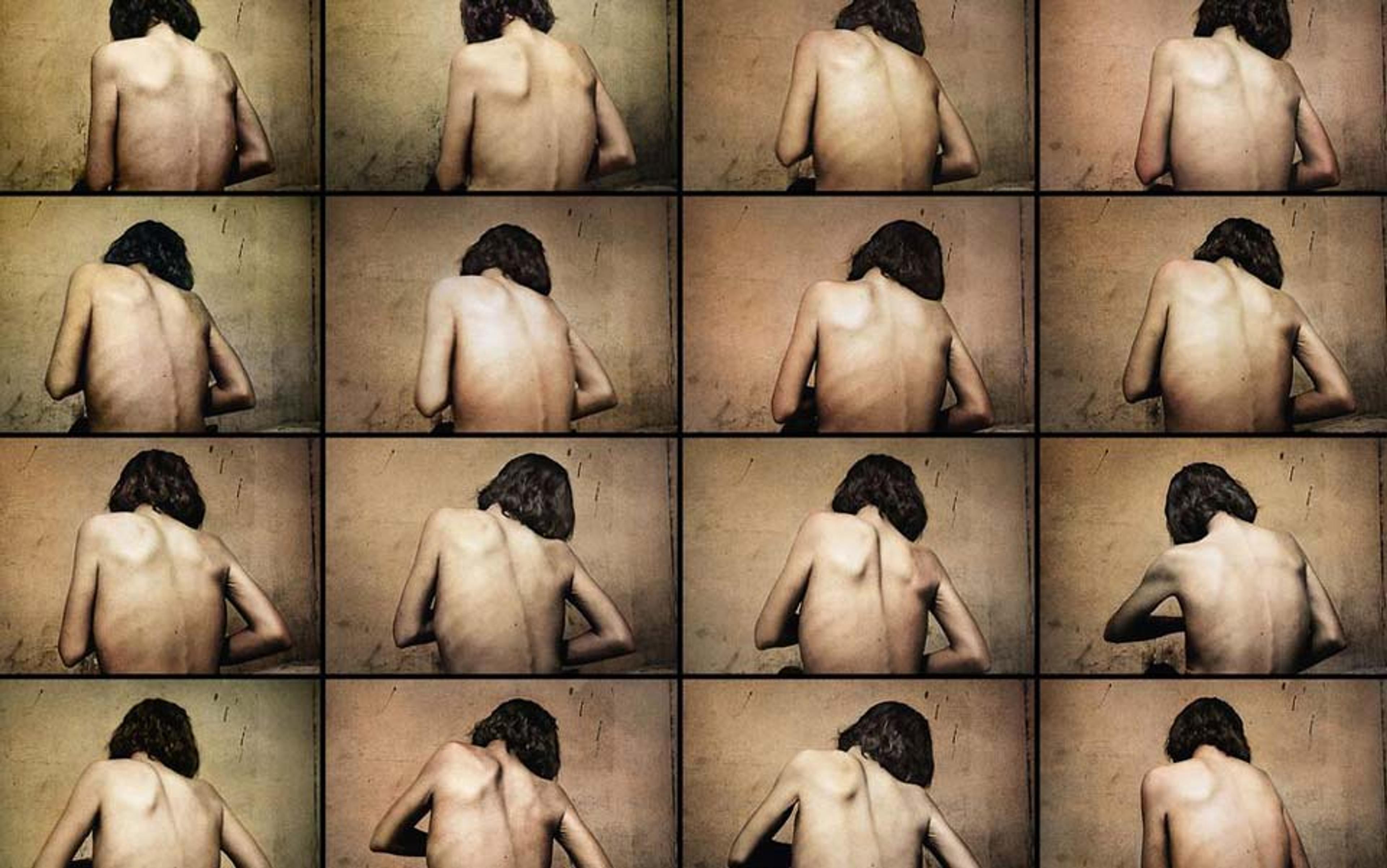

The problem is that this is just the kind of insanity our culture needs. All too often, Holly’s doctors see someone with a long-term, difficult-to-treat disorder, a young woman with a shaved head and a chip on her shoulder. They see a problem, not a person. Built into these observations are the tremendous power differentials between Holly and her physicians.

‘I have been completely disenfranchised as a patient. No one trusts me to know what’s in my best interests,’ Holly said.

And she has good reason to be angry at those in authority. Medicare has repeatedly denied the treatment she needs to recover from her eating disorder. Treatment facilities have failed to listen to her concerns. Clinicians have told her she’s beyond help and should just check into the state mental hospital.

‘Defiance isn’t a trait I can turn on and off. It’s part of who I am, and it’s the reason I’ve made it so far. It can be a raw deal – it’s a strength in some areas and a liability in others. But if I wasn’t defiant, I would be living in a hospital, and I wouldn’t have had a Master’s degree in education from Harvard,’ Holly says. ‘It’s why I’m still alive.’