When Gary Gilbert lost his job, it was devastating. A tradesman, he had joined his employer’s company only because he thought it offered a bit more security than endlessly chasing the next gig as a freelance operator, and that he could then provide a better future for his son. The layoff came without warning. ‘I was crushed,’ he recalled. ‘Oh God. I’ve cried at night about it.’

While the layoff shattered his hopes and, Gary believes, was unwarranted, he refused to blame his employer. ‘I had no reason to take that job,’ he explained. ‘I thought I was going to make a more stable environment, you know. And I was wrong, you know, but that – that was my fault. I shouldn’t have done it. I never should have let my guard down. I never should have put my livelihood in somebody else’s hands. It was the biggest mistake I ever made.’

Gary’s response is not untypical; recent research shows that Americans are more likely to blame themselves for job insecurity, even when it results from structural changes in the economy. I interviewed 80 people up and down the class ladder, and with varying experiences of job precariousness. I found that we do a lot to keep our strong feelings away from the employer – we shrug our shoulders in resignation, we talk about layoffs as new opportunities for growth, we even convince ourselves we are glad not to keep working there anyway. Most of all, we blame ourselves. And while that blame can be corrosive for both men and women, there is something unique in the scarring that results for men, who often see work as a primary measure of masculinity.

For working-class men, it is something of a crisis. There’s a lot of critical talk about the moral character of working-class men – generally conceived of as those with less than a college degree – and most of it revolves around work, reflecting some latent anxiety about who is shirking and who is carrying. We know they watch more television and do less childcare than working-class women, and are less likely than more affluent men to work long hours. Working-class men themselves value ‘being hardworking’ among the qualities they prize the most; for the white working-class men who march in the reserve army of US talk radio, working hard is highly prized, and deeply respected. It forms the bedrock of their outrage at those who, talk-radio culture likes to say, ‘refuse to work’. (For their part, black men value work but also talk about collective solidarity). Underneath the moral language on both sides is the notion of work as the arbiter of honour in the US.

Yet the landscape of jobs in the US has radically altered the configuration of who does what and for what benefit. In contrast to a few decades ago, a much higher percentage of women and people of colour are in the labour force: about 47 per cent of workers today are women, compared with 38 per cent in 1970, while the 36 per cent of non-white workers is almost double their proportion in 1980. Meanwhile, the proportion of men with full-time jobs has shrunk, from 80 per cent 45 years ago to just 66 per cent. The jobs men do have are also increasingly insecure – at first due to shifts in types of work across the economy but, since 1996, likely due to the spread of layoffs as a management tactic.

Work might still be a moral measure then, but the distribution of work is increasingly uneven, with some men working too much and many men working too little, and both ensnared in conditions not entirely of their making. For men at the top, work colonises ever more of the day’s 24 hours, while those at the bottom, such as Gary, can face despair, hopelessness, even – as was reported recently – declining life expectancy. And men’s changed relationship to work bears implications for their changed relationships at home.

Masculinity has long been written in men’s relationship to work and, despite the onset of feminism, involved fathering, and the ‘slacker’, this is even truer today. In 1979, there was a certain rationality to the link between income and hours: the more you made, the less you worked. The bottom 20 per cent of earners were more likely than the top 20 per cent to work very long hours. By 2006, that relationship had reversed. Now, the more money men make, the more likely they are to put in what are often called ‘killer hours’. What is behind the reversal? Why would rich men work longer?

Scholars debate the causes. Some credit the ‘long-hours premium’ that professional-managerial class men earn – meaning the extra money they get for near-constant availability and work – while others point to pay discrepancies within occupations acting as incentives for increased hours (men want to earn more than the guy in the next cubicle), and still others attribute the trend to anxieties about job insecurity that grew in the 1980s and ’90s for white-collar workers.

But these arguments overlook the emotional resonance of work, its profound capacity to tell us something about ourselves. What it signals to men is a form of honourable masculinity, as expressed in the moral code of ‘work devotion’, demanding an enormous time investment and emotional commitment to the career or employer.

Men of the professional-managerial class are the big winners in this transformation of work. For them, ‘insecurity’ can look like ‘flexibility’, as they jump from company to company in search of a better match for their skills. Highly educated workers are less likely than blue-collar or low-level service workers to suffer job displacement, and when they do, they experience less of a pay loss.

Still, it is well to remember that even at the top the choices can often be strangely constrained: for most men, their only ‘choice’ is either to work intensely or to get off the train. This all-or-nothing scenario has dramatic implications for men, women and families, impeding many men from being the fathers they want to be, funnelling out of promising careers many women who resist the extreme schedule and, for heterosexual couples, creating families that can explode over mismatched goals and possibilities, or conform to more traditional norms than the couple ever planned.

The transformation of work might have quickened the pace of the treadmill for professional men, but it has thrown other men off of it altogether. In the past 50 years, the number of men working full-time has fallen from 83 per cent to 66 per cent; between the 1970s and the ’90s, the proportion of jobs lost by prime-age working men almost doubled. The change was even more dramatic for black men, partly because disproportionate numbers of them in the US were employed in the dwindling manufacturing sector, not to mention the disproportionate impact of incarceration policies.

For those men who do work, pay has stagnated, with the purchasing power of the average hourly wage peaking more than 40 years ago – in 1973. These changes have accompanied the withering of unionised labour’s power, which the latest report puts at just 6.6 per cent of private-sector workers. Today, there are more than one and a half times as many ‘contingent workers’ as there are union members in the US.

What does it mean to prize something – to understand it as a primary measure of what it means to live a life of value – when it is becoming scarcer? How do men reconcile themselves to the likelihood of their own failure, particularly men with just a high‑school degree, who are unemployed at more than three times the rate of college graduates? If work is what it means to be a man, what do you do when work disappears?

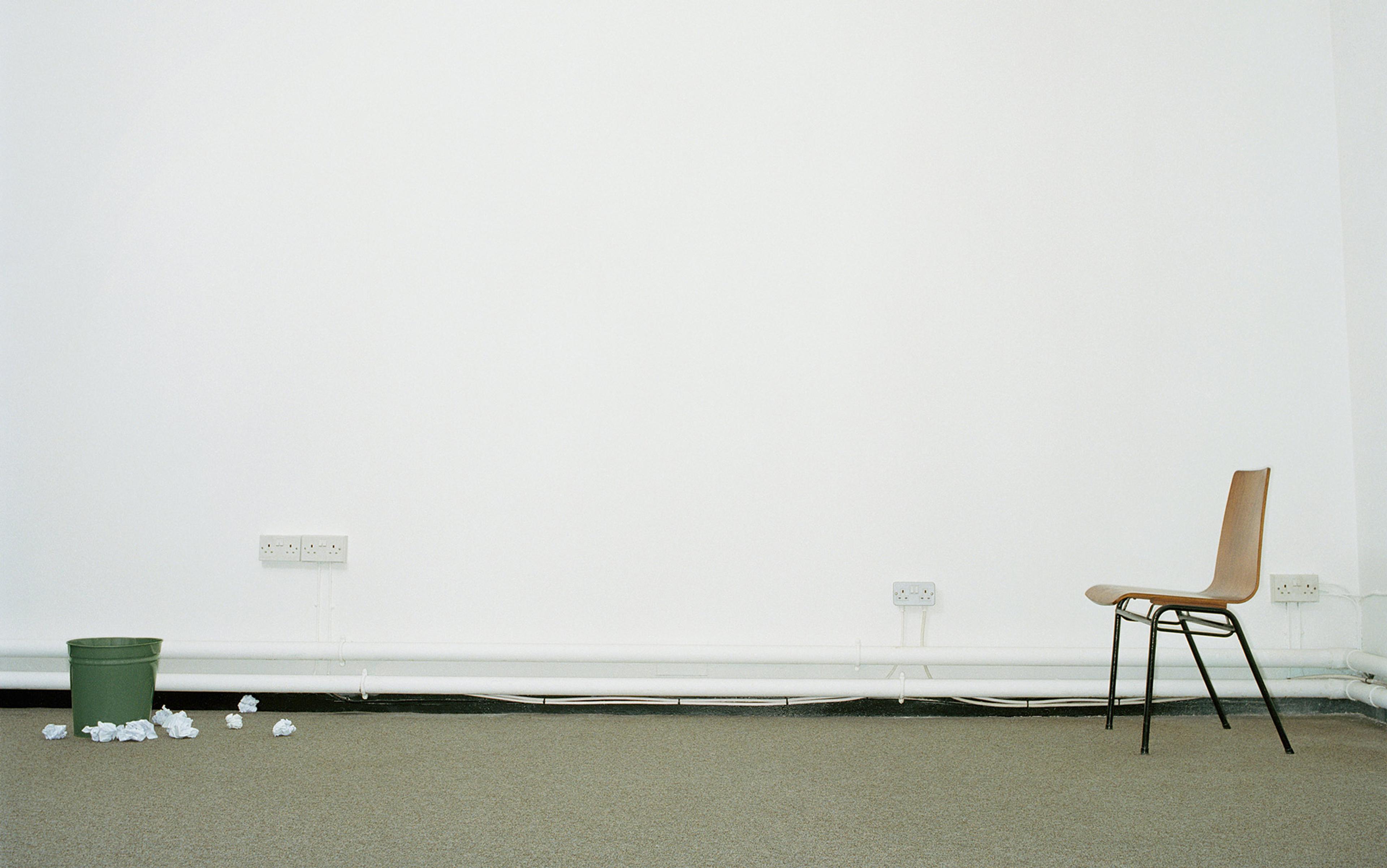

Abandoned by both employer and wife, Gary aims his ire at just one of these

One option is to get angry. When I interviewed laid-off men for my recent book on job insecurity, their anger, or more often a wry bitterness, was impossible to forget. By and large, like Gary the laid-off tradesman, they were not angry at their employers. At home, however, they sounded a different note. ‘I have a very set opinion of relationships and how females handle them,’ Gary told me, rather flatly. ‘It’s what I’ve seen consistently throughout my life.’ On his third serious relationship, Gary talked about the ‘hurt that’s been caused to me by a lack of commitment on the part of other people’, and he complained that ‘marriage can be tossed out like a Pepsi can’. In the winds of uncertainty, Gary’s anger at women keeps him grounded.

Most Americans might expect very little from their employers – as one layoff survivor told me: ‘Just a paycheck and a certain amount of respect, I would say.’ They might shrug their shoulders about job insecurity as the inevitable cost of doing business in a globalised economy (even though some economists have found that layoffs usually end up costing firms rather than boosting stock prices or productivity). At home, however, working‑class men expect more of their intimate partners, and brittle yearning turns those expectations into betrayal if they fall short. Abandoned by both employer and wife, Gary aims his ire at just one of these.

It is wrong, however, to read this anger as simply the outrage of a dethroned king who has lost his prerogative. Working-class men such as Gary long for a time when they had rights to women’s loyalty, deference and caring labour, and when, in their view, they earned that right by virtue of the hard work they themselves contributed. The transformation of work dislodged their ability to put up their share of this bargain, one that netted them benefits, to be sure, but also involved years of their backbreaking labour. It is this morality tale that enables them to count themselves wronged, and lends such intensity to their concerns about those mythical emblems of entitlement: able-bodied people who refuse to work. What they want, they maintain, is the opportunity to work hard for their rightful place, to be a working-class hero.

Perhaps a more powerful response to the transformation of work is to change what counts as honourable masculinity. Some men I spoke with seemed to be pursuing a form of ‘independence’. They owed employers as little as they themselves were owed – which they maintained was not very much indeed – and, at home, they cultivated a careful freedom, even when their feelings ran strong.

Stanley, an actor who had been laid off from several day jobs, was in the middle of a divorce. Bringing up the common trope of ‘working on a marriage’, he said that we need to redefine the term. ‘Because the work changes,’ he said. ‘The work can be in letting go. That’s the right thing to do. So, yeah, that’s all the work. Because I think bottling it up or denying it, if that’s what happens, it’s not going to work either.’ Independence dislodged men from domesticity, but although they sometimes celebrated it as freeing, their accounts often echoed with loneliness.

Others try to reshape masculinity not by shrinking obligation but by redirecting it towards the home. Clark had been laid off repeatedly, and was now struggling to bring in enough money by working part-time in retail and playing in a band on weekends. He talked a lot about how he was raising his daughter – making her home-cooked meals, meeting her at the bus, warning her about social media. ‘I wanted her to have a secure life, where she knew there was somebody there for her,’ he said.

Precisely because active fatherhood is not a choice but part of an honourable soul it becomes an alternative heroic masculinity

The news is full of stories of involved fathers doing it differently than their own distant dads. To be sure, stay-at-home moms still outnumber stay-at-home dads by about 100 to one and, while fathers who live with their children have doubled their childcare time, they spend fewer hours with children than do mothers; meanwhile the percentage of non‑resident fathers has increased sharply since 1960, with more than a third of children now living without their dads. Still, many men today are finding purpose and meaning in a close relationship to their children.

When I talked with men who were active caregivers, they would often inveigh against those well-meaning but clumsy comments from others exclaiming over their extraordinary dedication; as Owen described them: ‘Well-meaning people making comments like: “Oh, gosh. Most men would have walked away.” Yadda yadda yadda. And that used to make me so mad… I used to get offended by that.’ Characterising what they do as a commendable choice is annoying because it implies that they might not have stepped up to do this refashioned masculine duty. It is precisely that it is not a choice, but instead part of their good character, their honourable soul, that makes active fatherhood an alternative heroic masculinity.

Nonetheless, most working‑class men such as Gary are trapped by a changing economy and an intransigent masculinity. Faced with changes that reduce the options for less-educated men, they have essentially three choices, none of them very likely. They can pursue more education than their family background or their school success has prepared them for. They can find a low-wage job in a high-growth sector, positions that are often considered women’s work, such as a certified nursing assistant or retail cashier. Or they can take on more of the domestic labour at home, enabling their partners to take on more work to provide for the household. These are ‘choices’ that either force them to be class pioneers or gender insurgents in their quest for a sustainable heroism; while both are laudable, we can hardly expect them of most men, and yet this is precisely the dilemma that faces men today.

What does it take to turn the anger of despairing men into violence? The grief and antagonism that erupt after every school shooting focus on either a prevailing gun culture or mental health problems, but masculinity is surely an indispensable component. Research has shown that the roots of these paroxysms of violence are in the toxic relationship between ‘masculinity threat’ – a man’s individual perception that he cannot live up to the ideals of dominant masculinity – and a cultural betrayal, the sense that men are owed something they are no longer getting.

In the meantime, the code of work devotion is nothing but lucky for employers, part of the moral glue that keeps us all beholden to the job. But if there’s a love affair happening with work, it is in large part unrequited. Employers have backed away from the old reciprocity norms, while affluent men labour ceaselessly to prove their mettle, and less advantaged men languish in despair. Is there any way we can respond?

Masculinity has long involved social norms that are widely understood and upheld but that few can actually live up to

It is worth pointing out that work precariousness is not inescapable; policies that encourage longer-term employment do exist in other countries (and some states). They are of three kinds. The first rewards employers who want to offer stable work, through such ideas as ‘short-time compensation’, or the use of unemployment insurance to enable work-sharing instead of layoffs. The second builds stronger relationships between employers and workers, including incentives for workplace training, or an improved accountability framework holding employers responsible even for subcontracted or outsourced labour. The third makes it easier for workers to do their jobs well, such as paid parental leave or measures to improve unpredictable scheduling.

But there’s reason for skepticism about any policies that fall short of those that amplify labour’s voice, which in the US is now quite muted. Other rich countries with higher union density take steps to enable both employer flexibility and worker security, through income supports and retraining. In the US, better enforcement of labour law provisions that protect the right to organise would enable workers to slow down or impede layoffs, or to shape how they happen. A more subtle outcome would nonetheless be just as important: some scholars think that, just like the black church seems to do for black men, unions could remind more white working-class men to prize not just ‘hard work’ but also solidarity and other values.

While we can tackle the distribution and character of work, it is less clear whether we can dislodge its moral monopoly. Given radical economic shifts, perhaps more men will redefine the honourable, so that dominant masculinity reflects other traits and qualities, perhaps even contributions that more of them can reliably make. Still, we must not underestimate a core attribute about masculinity: it has long involved social norms that are widely understood and upheld but that only a few can actually live up to. Given that history, we cannot assume that the increased scarcity of a decent job will weaken the hold it has over honour, nor lead to masculinity’s remaking. That will require another seismic shift, this time in the cultural landscape.

Names have been changed to protect participants’ confidentiality; all quotes appear in The Tumbleweed Society (2015) by Allison J Pugh.