The night sky pulses with colour: streaks of viridian, azure, violet and crimson vivid against the bleached land. Leviathans roam the seas, singing in haunting voices, and white bears hunt toothed whales on land and water. Giants make their homes in the mountains; elves and trolls live among the rocks. Half the year is spent in darkness and perishing cold, bleak and treacherous, the other half in sunlight and warmth, the landscape lush and verdant. Here is a portal to another world. The tribal inhabitants, some more animal than human, live in harmony with their harsh environment, bridle at outside authority, and fight with terrible ferocity. You know this place well. It is the Fantasy North.

You have spent quite a bit of time here over the past few years, perhaps even without trying. The global success of Disney’s Frozen (2013) is only the tip of the iceberg. The trials of the Stark family and the coming battle north of the Wall in the novels of George R R Martin have been followed by tens of millions of readers in dozens of languages since his series A Song of Ice and Fire began publishing in 1996. The television adaptation, Game of Thrones likewise reaches a global audience of millions.

Alongside the trolls of Frozen and the giants and White Walkers of Westeros, Vikings have taken a prominent place on the cultural stage. Since the start of the 21st century, major museum exhibits on early Scandinavian culture have appeared worldwide, from Washington, DC and Berlin to Suzhou in China. Just recently in 2009, Northmen attacked the monasteries of Scotland and Ireland in the animated film The Secret of Kells; reluctant Scandinavian raiders visited northern England in Wells Tower’s book Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned; and a Norse slave sought his destiny against all challenges in Nicolas Winding Refn’s feature film Valhalla Rising.

And then there’s Ragnar Loðbrók and his kinfolk, whose saga has been unfolding in the TV drama Vikings (2013-). Very loosely based on the medieval texts that recount Ragnar’s adventures and those of his illustrious progeny in the 9th century, the History Channel’s show goes to some lengths to convey the strangeness of these pagan northerners, even amid the enveloping foreignness of the medieval period. Both the English and the Northmen speak in Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse at times; the rest of the time, they speak in British or Scandinavian-accented English, touched with a hint of archaism. But Ragnar and his fellows have elaborate tattoos and hairstyles. They have never heard of Rome or Paris. They consult a soothsayer, and make animal and human sacrifices to their gods. How accurate is any of this? Perhaps no less than the medieval sagas themselves. The Ragnar Loðbrók of the 12th-century History of the Danes by Saxo Grammaticus and the 13th-century Icelandic Saga of Ragnar Loðbrók probably bear little resemblance to any historical Ragnar Loðbrók, if he existed at all.

What is it about the current era that draws our gaze towards the top of the globe? Where does our fascination with ‘northernness’ come from? Within Western culture, the North has long been both an imaginary realm and a geographic place. Since the ancient period, it has been a land at the edge of the world, one that exists on its own terms and as a scrim for various fantasies. Many of those fantasies have been preserved intact, in a sort of cultural permafrost that keeps our interest in the North evergreen. But every so often, something stirs.

To the ancients, the lands of the far north, Hyperborea and Thule, both were and were not real places. They were ‘unknown lands’ (terrae incognitae) in Ptolemaic cartography, as they existed so far away from the Greeks and their neighbours that they were more legendary than real. To the Greek poet Pindar, writing in the 5th century BCE, Hyperborea, the land ‘beyond the north wind’ as its name implies, was a mythical place beyond the reach of ordinary people. Its fortunate inhabitants, untroubled by illness, old age, work or warfare, spent their days feasting and dancing. Perseus and Heracles, both heroes and both sons of the god Zeus, had been able to reach it. But they were special. Pindar cautioned his fully human audience: ‘[n]either by ship nor on foot would you find the marvellous road to the meeting-place of the Hyperboreans’. We find a contrasting opinion in the markedly prosier testimony of the historian Herodotus, writing at roughly the same time as Pindar. He considered that Hyperborea was a real place, albeit a very distant one. Located far to the north of Scythia or even the Celts, it nevertheless had an unusually temperate climate, where the sun shone all day and night.

Like Hyperborea, Thule was associated with real places as well as imaginary ones. Ancient Greek geographers referred to a now-lost work from the 4th century BCE that placed Thule six days’ sail north of the island of Britain. Later writers, trying to pin down this location – and thus the known limit of the world – identified the Orkney Islands, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Norway all as Thule. Both the Roman poet Virgil (70-19 BCE) and the late antique philosopher Boethius (c480-524 CE) referred to Thule as the northwestern limit of the world – beyond lay the terrible unknown. Thule’s significance as a zone both real and imaginary, both at and beyond the margin, became an enduring part of the cultural imagination. Take Edgar Allen Poe’s poem ‘Dream-Land’ (1844), in which a traveller explains:

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule –

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of space – Out of time.

During the early decades of the Roman Empire, the Greek geographer Strabo (c30 CE), the Roman natural historian Pliny (c77 CE), and the historian Tacitus (c98 CE) all situated Thule beyond Britain, which became part of the Roman Empire in 43 CE. As Rome expanded her boundaries northward, Roman writers drew on preexisting knowledge about the far north and also added new information. According to the historian Tacitus, the island of Britain possessed a moist, temperate climate, fertile soil and long, almost 24-hour days. Some of the northern tribes, the Scoti, strongly resembled the Germanic tribes. ‘The red hair and large limbs of the inhabitants of Caledonia [Scotland] point clearly to a German origin,’ wrote Tacitus. The Scoti, along with the Picts, another group that lived in the northern part of Britain, proved indomitable – so aggressive, in fact, that Emperor Hadrian ultimately erected a massive defensive fortification across northern Britain, known as Hadrian’s Wall. It wasn’t enough. Raids and incursions from the north continued, becoming troublesome enough in the 4th century to weigh in the emperor’s decision to withdraw from Britain.

Pagan pirates, they attacked almost without warning, carried off treasure and captives, and left cinematically smoldering ruins in their wake

Thanks to Tacitus and later writers who relied on him, the fierce tribes who lived beyond Hadrian’s Wall joined the mythical inhabitants of Thule and Hyperborea as totemic creatures of the North. Tacitus extolled the virtues of the people who lived beyond the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in several of his works. The Picts and the Scoti earned his respect for their refusal to yield their freedom, just as the Germanic tribes of northern Europe had impressed him with their bravery and dedication to family. Even as Tacitus offered ethnographic descriptions of northern tribes, he was also venturing into a fantasy realm, one free from the moral decay of civilisation. None of the Germanic tribes laugh at vice, he scolded his countrymen, ‘nor do they call it the fashion to corrupt and be corrupted’.

Several centuries later, a different group of northerners landed south of Hadrian’s Wall, confirming but also complicating the ideas of ‘northernness’ that had been inherited from the Greeks and the Romans. In 865, the ‘Great Army’ (led, according to later sagas, by the sons of Ragnar Loðbrók) invaded East Anglia. This confederate Scandinavian force ended up toppling three of the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms – Northumbria, East Anglia and Mercia – before finally meeting defeat at the hands of King Alfred the Great of Wessex in 878.

The Great Army was the largest invasion of Northmen, as they were known, into Britain thus far. Still, Scandinavian merchants and raiders had been travelling up and down the coast for decades. Most invasions were basically smash-and-grab jobs, like the raid on Lindisfarne monastery in 793. Wealthy churches had treasure of their own, and they often stored the movable wealth of their patrons. This made them inviting targets. For the next 70 years, the Northmen regularly harried coastal England, Scotland, the Hebrides, Ireland, France and Germany. Pagan pirates, they attacked almost without warning, carried off treasure and captives, and left cinematically smouldering ruins in their wake. Anonymous chroniclers at the wealthy abbey at Xanten, on the upper Rhine, dutifully recorded local and regional raids by the Northmen for several years in a row before declaring, with barely repressed rage in 849: ‘The heathen from the North wrought havoc in Christendom as usual and grew greater in strength, but it is revolting to say more of this matter.’

Over the next 150 years, the northerners established settlements and trading ties from Constantinople to North America, across the north Atlantic and into central and eastern Europe. Some of the places where the Northmen settled, such as Iceland, were very sparsely inhabited, and so provided ample land for settlement and colonisation. Political conflict on the continent provided other groups of Northmen opportunities to extract tribute or gain permanent control over new territory. This is what Rollo, or Hrolfr, the first duke of Normandy, did when he agreed to convert to Christianity and prevent other Norse pirates from sailing up the Seine and threatening Paris, in exchange for marriage to King Charles’s daughter, and control of Rouen and the land around it.

Some Northmen were somehow beyond human, berserks who had the strength and savagery of wolves or bears

And just as the Northmen’s unwavering courage and chilling efficiency in battle confirmed existing stereotypes about northerners, examples of their pride seemed to confirm those ideas, too. When Rollo was told to kiss King Charles’s foot in exchange for his duchy, he flatly refused: ‘Never will I bend the knee to anyone, or kiss anybody’s foot.’ He ordered one of his warriors to kiss the king’s foot in his place. This deputy raised Charles’s foot so fast that the king fell down on his backside.

The Hyperboreans might have shared the Northmen’s vigorous physicality and love of feasting, but the likeness between the two groups did not extend any farther. Where the pacific Hyperboreans cultivated the good life and had no need for warfare, the Northmen were notoriously ruthless, attacking the unarmed and the weak alongside the strong. Alcuin, a Northumbrian cleric at the court of Charlemagne, lamented after the attack on Lindisfarne: ‘the pagans have desecrated God’s sanctuary, shed the blood of saints around the altar, laid waste the house of our hope and trampled the bodies of the saints like dung in the street’. In truth, Viking leaders were no more murderous than their Christian counterparts, including Charlemagne. Some writers fused more recent accounts of Viking raids with older ideas about the particular savagery of northerners and with the notion that the North was home to strange creatures. They insisted that some Northmen were beyond human, that these berserks had the strength and savagery of wolves or bears.

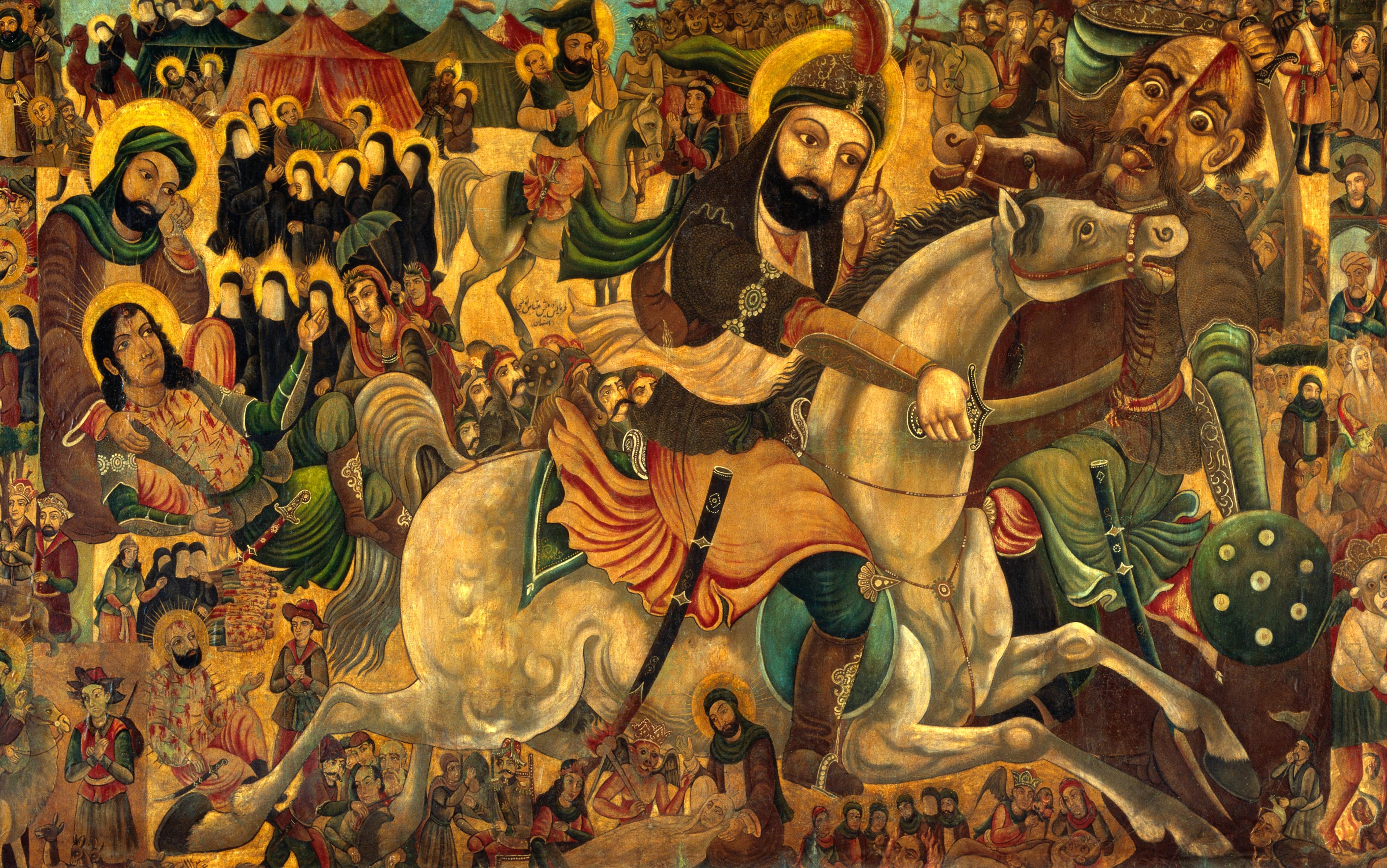

Many writers, going back to the ancient period, noted the imposing build and pale colouring of northerners. To some, however, their appealing vigour couldn’t compensate for their disgusting habits. According to Ahmad ibn Fadlan, an ambassador from Caliph al-Muqtadir in Baghdad to the Bulgars on the Volga River in 921 CE, the Rus (as the Northmen who had settled in the area were known) were physically impressive: ‘I have never seen more perfect physiques than theirs – they are like palm trees, are fair and reddish…’ But, he complained, they rarely bathed and never washed their hands, even after eating or relieving themselves. ‘They are the filthiest of all God’s creatures… Indeed, they are like asses that roam in the fields.’

Time wore away some of their strangeness. By the end of the 11th century, the pagan Northmen had converted to Christianity, and were able to earn more from peaceful trade than from piracy. As the Viking Age drew to a close, the arctic regions gradually lost their association with the threat of invaders, evoking instead a marvellous bounty of wealth and wonder. The Hanseatic League – a confederation of market towns around the North Sea and the Baltic Sea – controlled the trade in walrus ivory, furs and fish, among other things. Majestic Arctic gyrfalcons remained the preferred hunting birds of kings and princes across Eurasia right into the early modern period. Polar bears were sought-after trophies: King Haakon of Norway sent one as a gift to England’s King Henry III in 1252, and polar bears also appeared in cabinets of natural wonders in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Yet the North remained at the limit of the known world. European explorers in the 16th and 17th centuries insisted that the unmapped contours of the far north promised the shortest trade route to the Far East, and that the northern extremes of North America likewise offered a route to China. From the 16th to the 19th centuries, merchant companies, sovereigns and adventurers alike mounted dozens of expeditions to find the Northeast and Northwest Passages, as these hypothetical sea routes were known. The continuing mystery of what the world looked like at the top of the globe allowed the North to retain its association with fantasy, myth and adventure. In The Blazing World (1668), a remarkable work of prose fiction by the scientist and writer Margaret Cavendish, the portal to a parallel utopia inhabited by intelligent talking animals was located at the North Pole.

By the early modern period, most of the recognisable characteristics of our Fantasy North had taken shape. But it was only in the 19th century that the polar regions began to exercise a distinctively political allure. Walter Scott echoed the admiration of Tacitus for the fierce independence of the northern tribes when he romanticised the clans of the Scottish Highlands – whose way of life had been destroyed just a few generations earlier after a failed rebellion against the English – in his novel Waverley (1814). Just as in the film Braveheart (1995), the Scots in Waverley are torn between resisting the tyrannical English and collaborating with them. Naturally, the rebels get all the best parts and the most stirring speeches, even though they are doomed to defeat.

Waverley was a huge success, and Scott became known as ‘The Wizard of the North’. His template has proven durable. The wildly popular series Outlander (1991) by Diana Gabaldon is set amid the Jacobite rebellion that Scott immortalised, and develops its themes within a very Scott-ish frame. Similarly, the aggressive northern ‘Free Folk’ – meaning that they live free of allegiance to a distant king, and also that they live beyond the boundary of civilisation in an unforgiving land – of Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire represent a sort of Scott-Tacitus hybrid: they are at once glorious, doomed rebels and also the weird and shaggy emblems of a vigorous otherness.

Interest in the North came from other quarters, too. An obsession with the Middle Ages – both revivalist and revisionist – gripped European culture in the 19th century, and the reputation of medieval Scandinavia improved dramatically. No longer bloodthirsty heathen pirates, the Northmen were recognised as superb marine engineers and navigators. In 1837 Carl Christian Rafn, a Danish antiquarian, argued that the Vinland sagas – the two 13th-century sagas (of Erik the Red and of the Greenlanders) detailing Norse voyages to Vinland – reveal that Leif Ericksson and others sailed from Greenland to North America in the late 10th century. Within just a few years, his provocative treatise was translated into English, circulating widely under the title The Discovery of America by the Northmen in the Tenth Century. Challenging the established view that the Vinland sagas were complete fiction, Rafn and his adherents presented a compelling precedent for trans-Atlantic exploration, carried out by northern Europeans 500 years before the voyages of Christopher Columbus.

Though himself plagued by ill health, Nietzsche insisted that the vigorous and strong were born to dominate the weak

The narrative of the Norse ‘discovery’ of North America became further ammunition for proponents of white supremacy. Many educated people believed that the different races of the world had arisen at separate times, as distinct species, and were biologically different in meaningful ways. This theory, known as polygenism, held that the first and best species to emerge was the Caucasian or white race. Influential scientists and philosophers used such ideas as a way to rationalise the subjection of non-white people: these latter groups were, according to many, biologically and intellectually inferior.

Within the so-called white race, the northern sub-group – Nordic, Teutonic or Aryan, as it was variously known – was defined by an imposing physique, fair hair and blue eyes. This northern group was considered to be the purest and most complete expression of human potential and ability. In accordance with the scientific racism of the 19th century, the inhabitants of the North were no longer the filthy, merciless beasts they had been since before the medieval period. Instead, adherents of polygenism and white supremacy idealised a different northerner, one that affirmed the prevailing racist beliefs and resembled the ancient descriptions of the Hyperboreans: tall, golden-haired and heroic.

Such beliefs found many forms of expression throughout the 19th century. The German composer Richard Wagner – influenced by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s claim that the ‘white races’ had produced the highest civilisation and culture – asserted that only the Teutonic people had the capacity to create and appreciate profound art, as they were the most culturally refined. Wagner naturally expressed this Teutonic nationalism via repurposed medieval Norse myths – the most fitting source material for his masterwork, a series of four linked operas collectively known as the Ring cycle.

During the period of German unification in the mid-19th century, Germans also looked to Tacitus for their own origin story. Several of Tacitus’s claims about the Germanic tribes – about their fair colouring and blue eyes, great height and military ability – echoed contemporary ideas about the presumed superiority of ‘the Teutonic people’. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, for a time an adherent of both Schopenhauer and Wagner, looked north to find an indigenous European religious tradition that offered an alternative to narrow-minded Christian morality. He idealised the vitality and toughness both of northerners and what he called ‘tropical man’, writing enthusiastically about ‘blond beasts’ descending on the hapless and slavish peoples of the south. This was, in his view, an expression of the natural order, one unadulterated by morals that forced people to suppress their instincts. Though himself plagued by ill health for much of his life, Nietzsche insisted that the vigorous and strong were born to dominate the weak.

For the Nazis, the Fantasy North was their homeland and also the homeland of white supremacy

In the United States, interest in the Vikings surged in the second half of the 19th century for more prosaic reasons: there was a large influx of Scandinavian immigrants. US writers extolled the muscular vim of the Nordic people, not to mention their strikingly blond hair and piercing blue eyes. Scandinavian immigrants took up the idea that the Vikings had settled in North America to provide historical precedent for their own voyages and re-settlement. In 1898, a runestone discovered in northern Minnesota seemed to indicate that an expedition from the Norse settlement at Vinland had been attacked by Native Americans in 1362. The Kensington Runestone, as this artefact became known, is actually a 19th-century fake. It offers a fictionalised version of past events, suggesting a long-standing Scandinavian settlement in North America that endured centuries longer than the short-lived Vinland settlement lasted in reality. And it also gives a convenient, if false, reason for why the Norse settlers failed to make a more lasting impact in North America – they were driven out by the people already living there.

Writers in the 20th century continued to invoke ideas about the northern environment to rationalise their fantasies of white supremacy. The US eugenicist Madison Grant, author of the enormously popular The Passing of the Great Race (1916), insisted that ‘the Nordic race’ was responsible for the best of western civilisation because the harsh sunlight of the long summers and the bitter cold and high winds of the dark winters bred virility and selected against ‘defectives’. Like Grant, the contemporary US eugenicist Lothrop Stoddard held that the ‘Nordic race’ represented the pinnacle of all the ‘white races’. In his popular and influential book, The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White World-Supremacy (1920), he warned that the innate superiority of the ‘white race’ would be undermined by immigration of ‘colored races’ into North American and European countries.

Similar views were of course taken up by Hitler and the Nazis. The Nazis found additional rationalisations for their doctrine of white supremacy in the work of their compatriots Wagner and Nietzsche, and they looked to Tacitus for their mythical origin story as the German volk or ‘people’. Hitler and many other high-ranking members of the Nazi Party were members of the Thule Society – a white supremacist group interested in racial science and the mythical northern origins of the ‘Aryan race’. For the Nazis, the Fantasy North was their homeland and also the homeland of white supremacy, of Pindar’s comely Hyperboreans mixed with Grant’s hardy Nordic specimens.

There is, of course, nothing inherently racist about enthusiasm for the Vikings – they certainly warrant fascination. And medieval Scandinavians were not concerned with racial purity or their own ‘whiteness’ – indeed, such concepts would have been foreign to them. Their current popularity is largely expressive of an abiding interest – going back to the ancient period – in one version of the Fantasy North. The Vikings are an example – like the Free Folk of Westeros and the Scots in Outlander – of unfamiliar, charismatic, warlike people living in a stunning and difficult northern environment.

But ever since the 19th and early 20th centuries, the idea of ‘northernness’ that is so central to white supremacy has become an inextricable element of our Fantasy North. Many white supremacists view ‘the Nordic race’ as exemplary of white racial purity, and defend a fantasy of authentic whiteness in the guise of protecting cultural heritage. Nativist groups have grown more prominent on the far right throughout Europe and the US. Emblazoned in runes, organising under names such as the Aryan Brotherhood or the White Order of Thule, their members recite the slogans ‘Mass Immigration – Genocide of White Nations’ and ‘Diversity Is A Code Word for White Genocide’.

Perhaps this helps to explain why the Fantasy North has been enjoying its own cultural springtime. The iconography might be less visible, but white supremacist views are certainly making their way into the political mainstream. News outlets, politicians and pundits alike reference the ‘rising tide’ of people from outside the borders of European countries or the US. The story told by the Kensington Runestone – of a group of northern Europeans under attack – has found traction among many in North America and northern Europe who feel threatened by massive economic and demographic change. Xenophobia, racism and anti-immigrant sentiment have increased dramatically throughout Europe and North America since 2001. More recently, the frequency of violent crimes against people of colour, Muslims, Jews, and Sikhs has spiked in response to the Syrian refugee crisis and recent terrorist incidents. Meanwhile, in the Fantasy North white hegemony remains uncontested.

Our current arctic reveries reflect the challenges of the moment. As the globe gets hotter and drier, the cold and flourishing northern landscape becomes even more appealing. Those troubled by increasing state authority, political graft and industrial ruin can find inspiration in the stories of the proud, uncorrupted rebels who inhabit the North. And for some, fantasies of strength and conquest become attractive in hostile political and economic conditions. Whatever expression these desires and fantasies take, they all draw on a set of ideas about the North that reaches back through the 19th century into the depths of recorded history. But we might well shiver at the thought of what lies hidden beneath the ice.