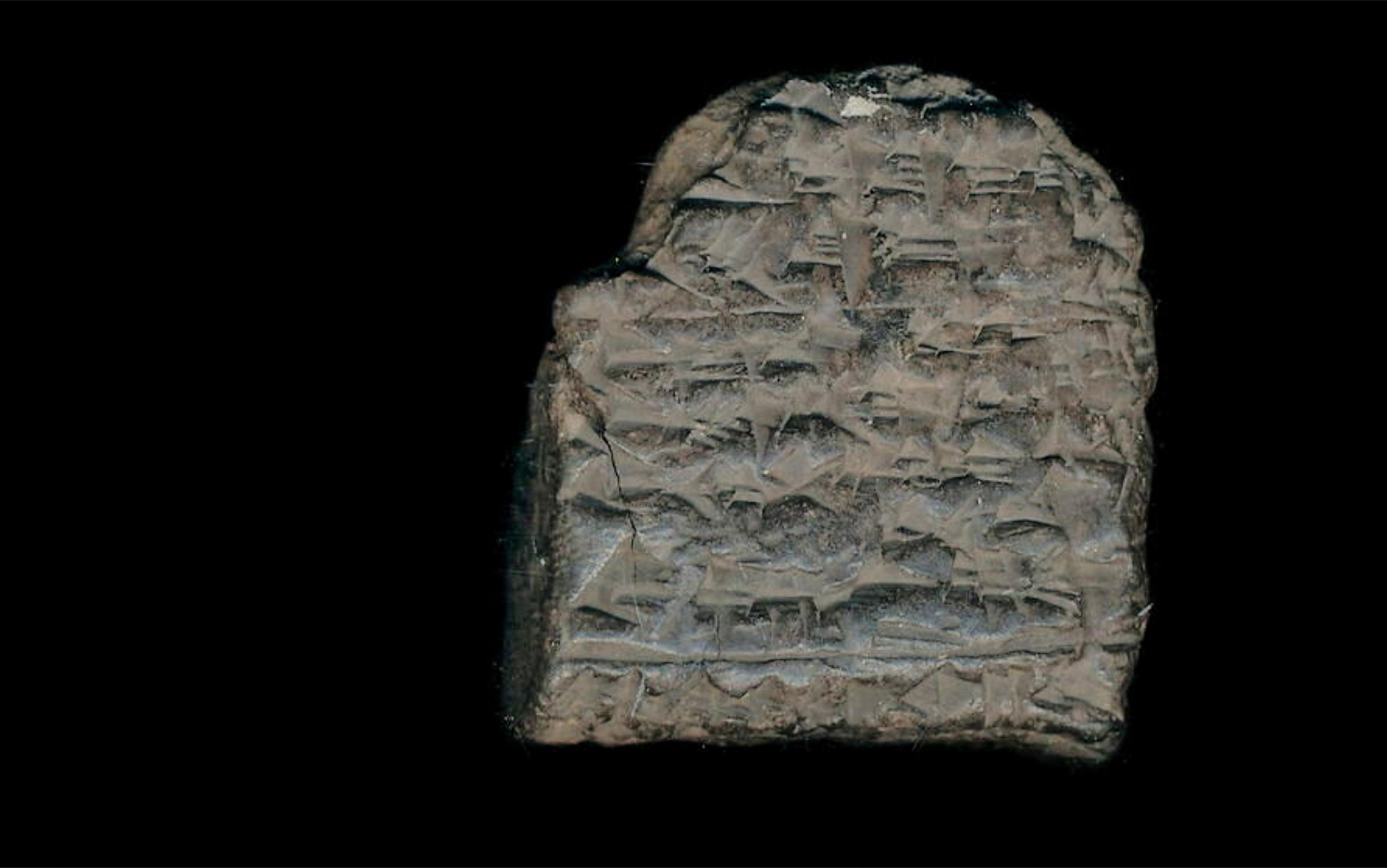

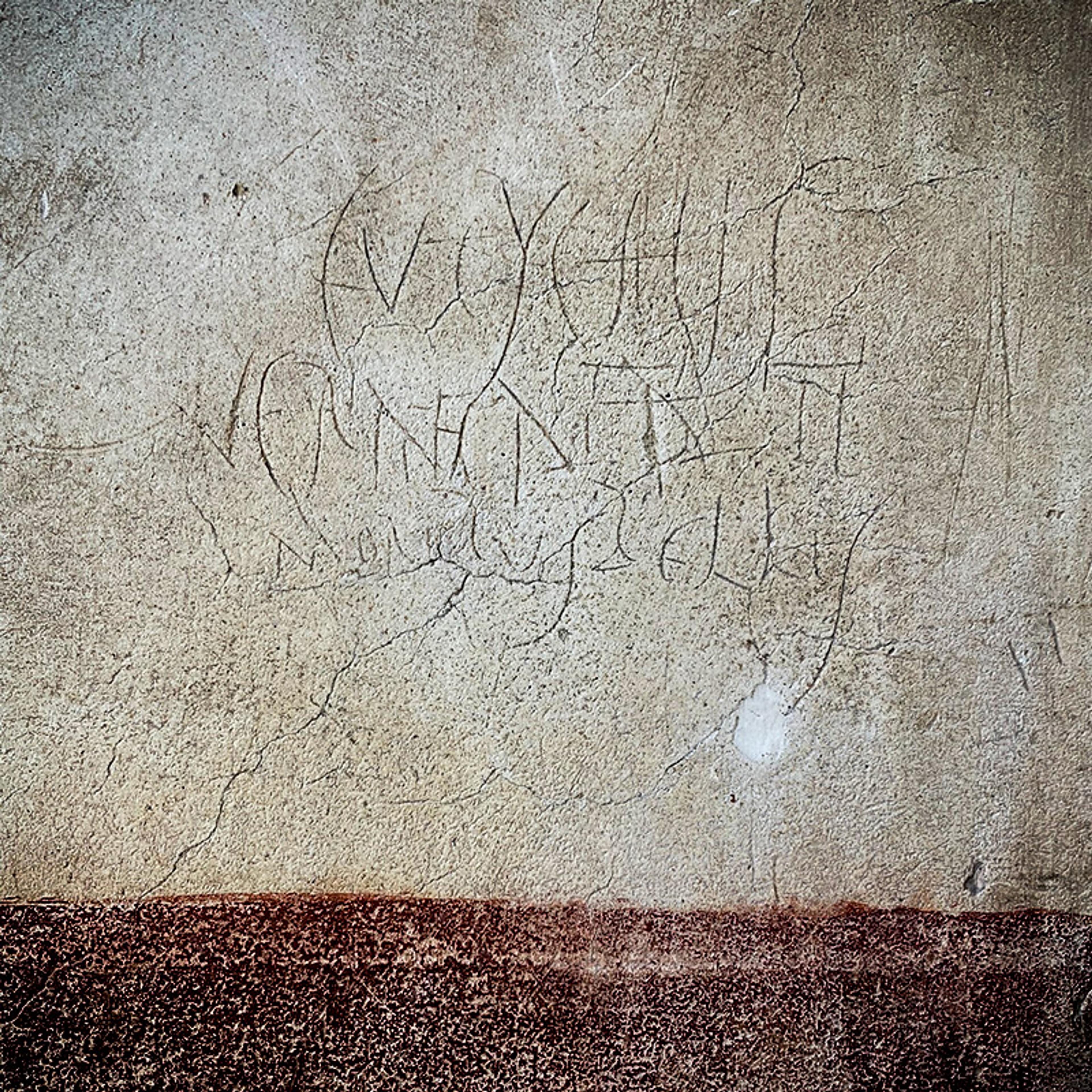

‘Eutychis, a Greek lass with sweet ways, 2 asses.’ This pithy graffito advertising sex for sale comes from the walls of Pompeii. The ancient Roman city was already an old town when it was destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in August 79 CE – and thus preserved for posterity. Located on the Bay of Naples, near the mouth of the river Sarno, there are early signs of Etruscan culture, though the area was later settled by Oscan-speaking Samnites, who began the town’s real growth after around 200 BCE. The land around Pompeii was fertile, and the city and region grew wealthy.

‘Eutychis, a Greek lass with sweet ways, 2 asses’; grafitto at the entrance to the Lupanar, Pompeii. Photo courtesy Pompeii Sites

As Rome expanded its power throughout Italy, Pompeii became a Roman city, though one that retained a diverse population. We can imagine a busy place of some 12,000 people, rich and poor, free and enslaved, of public squares, fountains and gardens, fine houses and poorer dwellings, taverns, shops and workshops, and a stone amphitheatre for the provision of large-scale public entertainment. There would have been a clamour of Oscan, Greek and Latin, and all the activities we would expect from a thriving town – politics, business, love, crime.

Graffiti is one of the most exciting kinds of evidence preserved for us by the destruction of Pompeii, because it comes not from the literature of the elite, or the inscriptions of the powerful, but from a wider cross-section of society. The Eutychis graffito gives us a woman’s name, an ethnicity, a price, the hint of a good time to be had – and suggests a seamy side to the ruined town now frequented by inquisitive tourists and keen culture-vultures. It was written on the vestibule wall of a well-to-do house owned by two freedmen, the Vettii, which is perhaps best known to the world for its painting of the well-endowed Priapus weighing his member on a balance against a bag of coins. While brief and to the point, this announcement, calling out to us from nearly 2,000 years ago, can set us on a journey to understanding more about the life of Pompeii’s haves and have-nots. At the same time, it may well leave us with more questions than answers about Eutychis herself and the prostitutes of Pompeii.

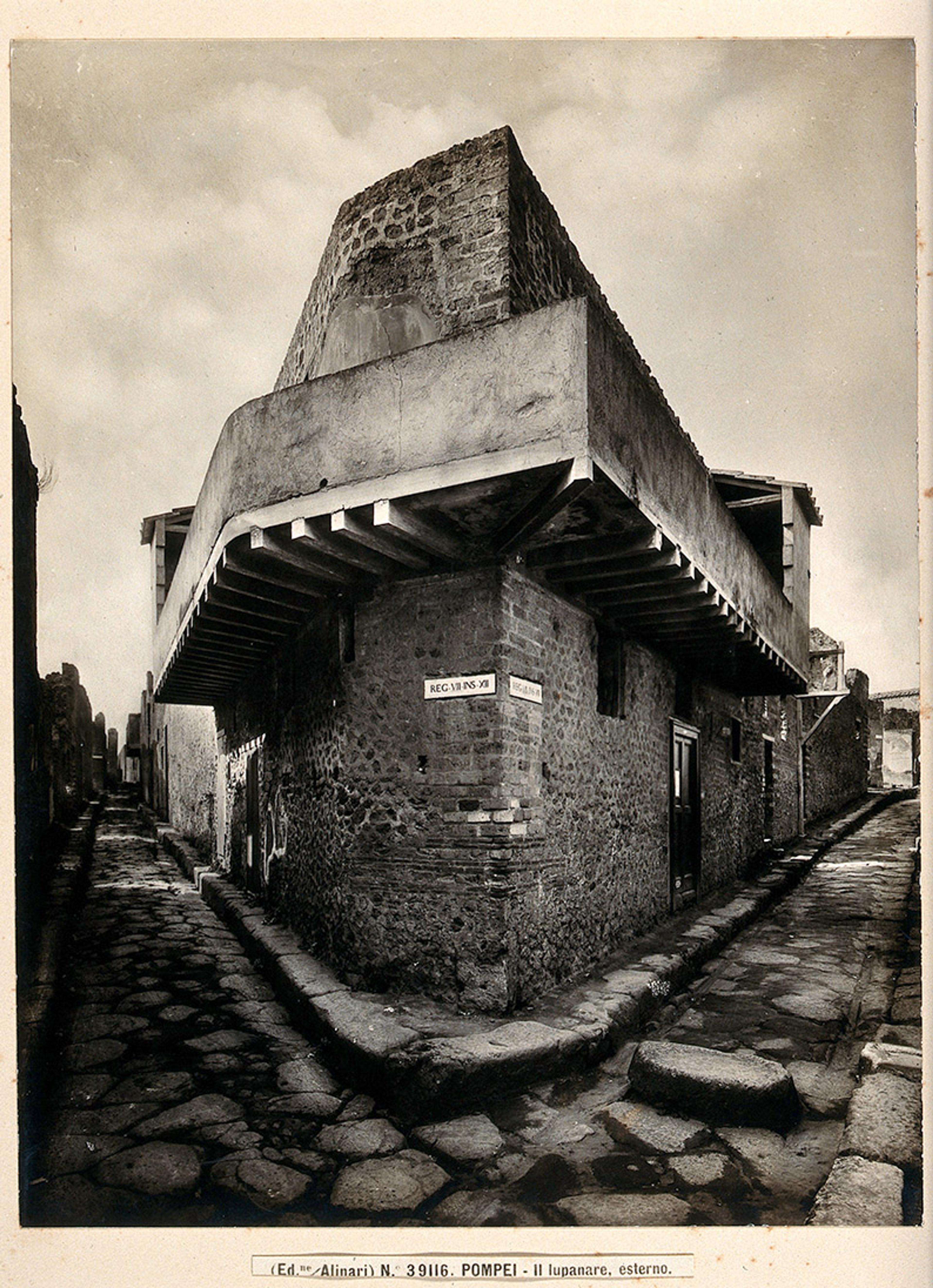

The Lupanar brothel, Pompeii. Photo courtesy Wellcome Images

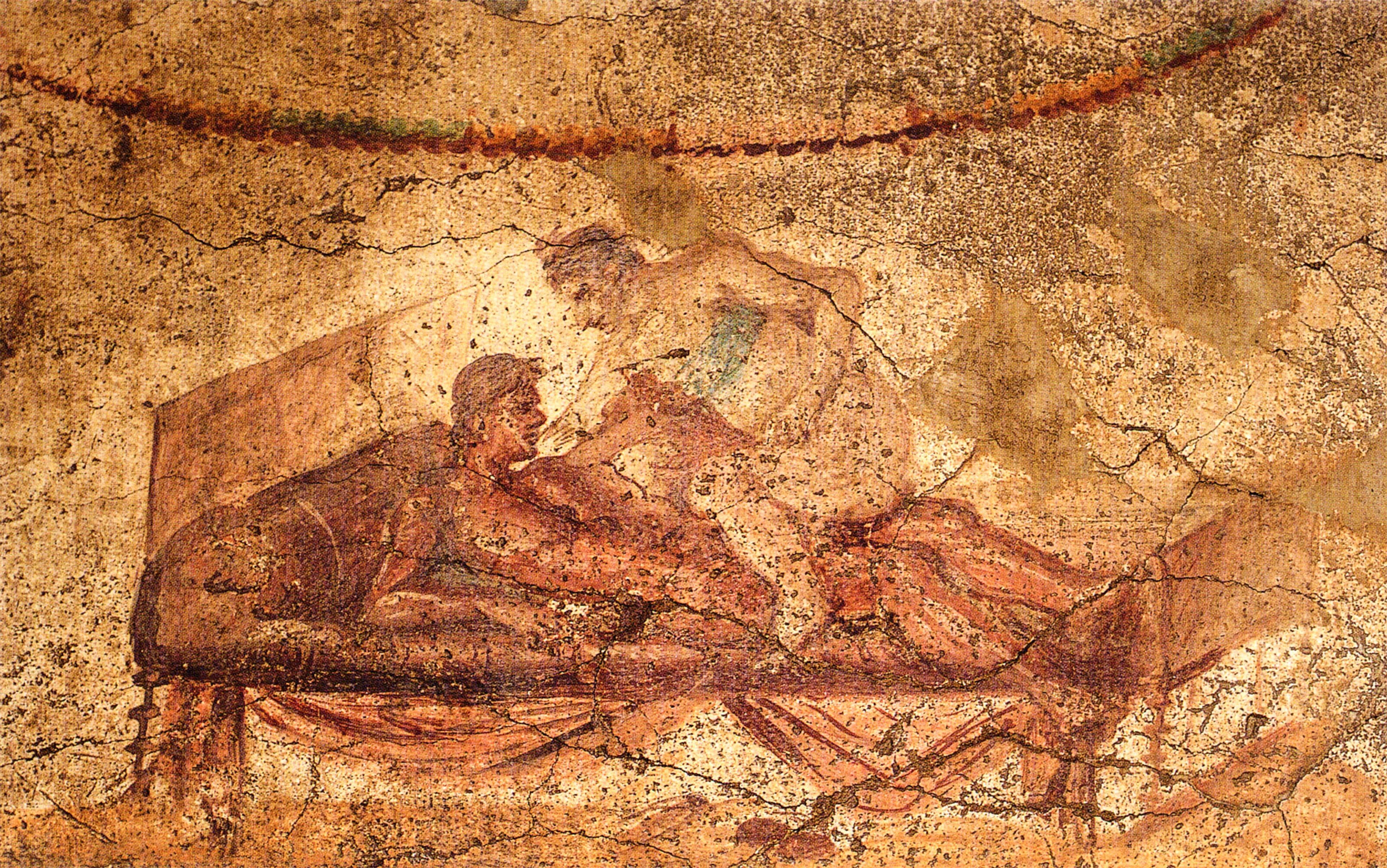

Pompeii, often seen under the bright sun with hordes of other visitors, does not hide its darker side – in fact, the single purpose-built brothel identified in the city, known as the Lupanar, is one of its most popular attractions. The sexy frescoes are one highlight. Eight can be seen above the doorways of the little cubicles with their masonry ‘beds’. Five or six are female-male sex scenes, another shows a woman standing next to a reclining man as she points at an erotic picture, and the last depicts the god Priapus with two erect phalluses. These show something very basic and timeless that we have in common with ancient Pompeiians – sex – but they also titillate the visitor and sometimes prompt dirty jokes from both guides and visitors. The frescoes presumably indicate the kind of activities that were available to customers, and helped in creating an erotically charged atmosphere.

Masonry bed at the Lupinar

Erotic fresco from the Lupanar

Priapus depicted with two penises; fresco at the Lupanar. All courtesy Wikipedia

Thanks to the graffiti in the brothel, we even know the names of some of the women who worked there: Anedia, Aplonia, Atthis, Beronice, Cadia, Cressa, Drauca, Fabia, Faustilla, Felicla, Fortunata, Habenda, Helpis, Ianuaria, Ias, Mola, Murtis, Myrtale, Mysis, Nais, Panta, Restituta, Rusatia, Scepsis, Victoria, and the daughter of Salvius. Eutychis does not appear in the list, although it might well be that those were working names; some of them appear in graffiti elsewhere in town.

They were on display naked with prices, to be perused, evaluated and chosen by the male clientele

How would Pompeiians and other visitors have experienced the brothel? We can learn something of this from a fragmentary literary text called The Satyricon, written in the 1st century CE by an elite Roman called Petronius. In the scene, the male character Encolpius has become lost in town. An old woman tricks him into entering the brothel, whereupon:

I noticed some men and naked women walking cautiously about among placards of price. Too late, too late I realised that I had been taken into a bawdy-house. I cursed the cunning old woman, and covered my head, and began to run through the brothel to another part, when just at the entrance Ascyltos met me, as tired as I was, and half-dead. It looked as though the same old lady had brought him there. I hailed him with a laugh, and asked him what he was doing in such an unpleasant spot.

He mopped himself with his hands and said: ‘If you only knew what has happened to me.’ ‘What is it?’ I said. ‘Well,’ he said, on the point of fainting, ‘I was wandering all over the town without finding where I had left my lodgings, when a respectable person came up to me and very kindly offered to direct me. He took me round a number of dark turnings and brought me out here, and then began to offer me money and solicit me. A woman got threepence out of me for a room, and he had already seized me. The worst would have happened if I had not been stronger than he.’

Petronius was writing comedy, but there is no reason to dispute the incidental details, which can bring the Lupanar to life. His description suggests brothels would be located in more out-of-the-way parts of town and were not necessarily identifiable from the outside; the prostitutes and punters were screened from the outside world by a curtain. It also reveals that people could be enticed or tricked into visiting – presumably chaperones who drummed up trade got a fee. The prostitutes themselves were on display naked with prices, to be perused, evaluated and chosen by the male clientele. Cubicles or rooms could be rented out for private use.

The Roman poet Horace wrote about men’s choice of sexual partners in one of his satires, where he is pointing out the follies of some men – especially in hankering after or having affairs with elite or married women. He suggests that prostitutes are a much more sensible choice when a man had need of sex. For one thing, their faces and bodies are visible, he says. In contrast to respectable women, whose bodies were well covered, prostitutes’ clothes could be revealing, allowing the man to view what he might want to buy and use. And, during the encounter, Horace says, a man might call the prostitute by any name – she could be expected to cater better to man’s fantasies. Horace, at least in character, preferred these women to be fair and natural, smartly turned out, prompt and inexpensive.

The Satyricon begins to fill in the details of the lives and environment of some prostitutes – those who worked in brothels, at least – but, so far, from the text and the paintings we have something of a light-hearted view of what went on. However, the reality of the women in the brothel, naked and carrying their price placards, was a grim one: their bodies put to use for the profit of the brothel’s owners, their physical and emotional work performed in tiny open cubicles or sex booths. Most of them were slaves, who had little choice in what they were doing, at the mercy of their owners and customers. Poorer free women too were vulnerable and had probably been driven to prostitution by necessity. About a fifth of the women’s names in the brothel indicate they were free.

Slavery was an accepted institution in the Roman Empire, and slaves of all kinds – agricultural workers, urban house slaves, labourers, miners, teachers (and prostitutes) – were everywhere. Some few slaves may have lived relatively privileged lives, and others had a degree of independence in their work and life, within the confines of being owned; some could even hope to be made free. But there are also sombre reminders of the less fortunate. Columella, also writing in the 1st century CE, explained how slaves on the farm should be treated and managed. He recommended their constant supervision and physical restraint in chains and in slave prisons (ergastula), as well as keeping control over where they could go, whom they could see, and also their bathing, religious practices and sex. What was the regime like for slave prostitutes in the Lupanar?

Slaves often had no space of their own but were simply part of the furniture

Enslaved people might be denied a love or sex life of their own but also be forced to reproduce (a source of new slaves), while female slaves might be forced into sex to help control male slaves. Sexual abuse and rape by owners was one particular vulnerability of slaves, female and male, child and adult. Many slaves could expect to be used sexually by their owners as a matter of course, perhaps household slaves in particular given their proximity. In another satire, Horace gives the line: ‘When your organ is stiff, and a servant girl or a young boy from the household is near at hand and you know you can make an immediate assault, would you sooner burst with tension?’ He also wrote an ode on the topic, advising his friend not to be ashamed of loving his slave when Achilles and other heroes did the same. A gold armband from Pompeii hints at this kind of relationship; it carries the legend ‘from the master to his slave girl’. Yet as well as perhaps being an earnest gift, it was also a reminder of who was who in the relationship. Sometimes, slaves may have been able to leverage sex to their advantage.

Archaeology furnishes more tangible evidence of the life of the enslaved. The relative absence of slave quarters in elite houses suggests that slaves often had no space of their own but were simply part of the furniture. They may have hidden and slept where they could, including making use of the spaces under staircases and dark and unpleasant cellars. These cellars could have other uses too. At Pompeii, in the Villa of the Mosaic Columns, the skeleton of a slave was found in a cellar with iron shackles anchored into the ground. This seems to have been a slave prison. Leg irons were found in a cupboard in the House of the Venus in Bikini, perhaps a half-hidden but lingering threat to coerce slaves into good behaviour. Beatings and whippings and the threat of violence were commonplace means of control and punishment by slaveowners. There was not only the physical pain involved, but also the humiliation of such a personal affront, which the victim was powerless to prevent. Compulsion and coercion were enforced psychologically as well as physically. Perhaps the Lupanar had its own ‘bouncers’, ready to deal with any trouble from customers or from the women themselves.

Enslaved people did resist and some did manage to run away. One nameless slave from Bulla Regia, in north Africa, was put in a lead collar inscribed: ‘This is a cheating whore! Seize her because she escaped from Bulla Regia.’ The collar was found with a skeleton in the Temple of Apollo. Nobody knows the name of the woman who wore it. Did she die seeking shelter in the abandoned temple? Was this her first attempt to flee or had she tried before and then been collared? This woman is almost lost in history, unknown apart from the symbol of her captivity.

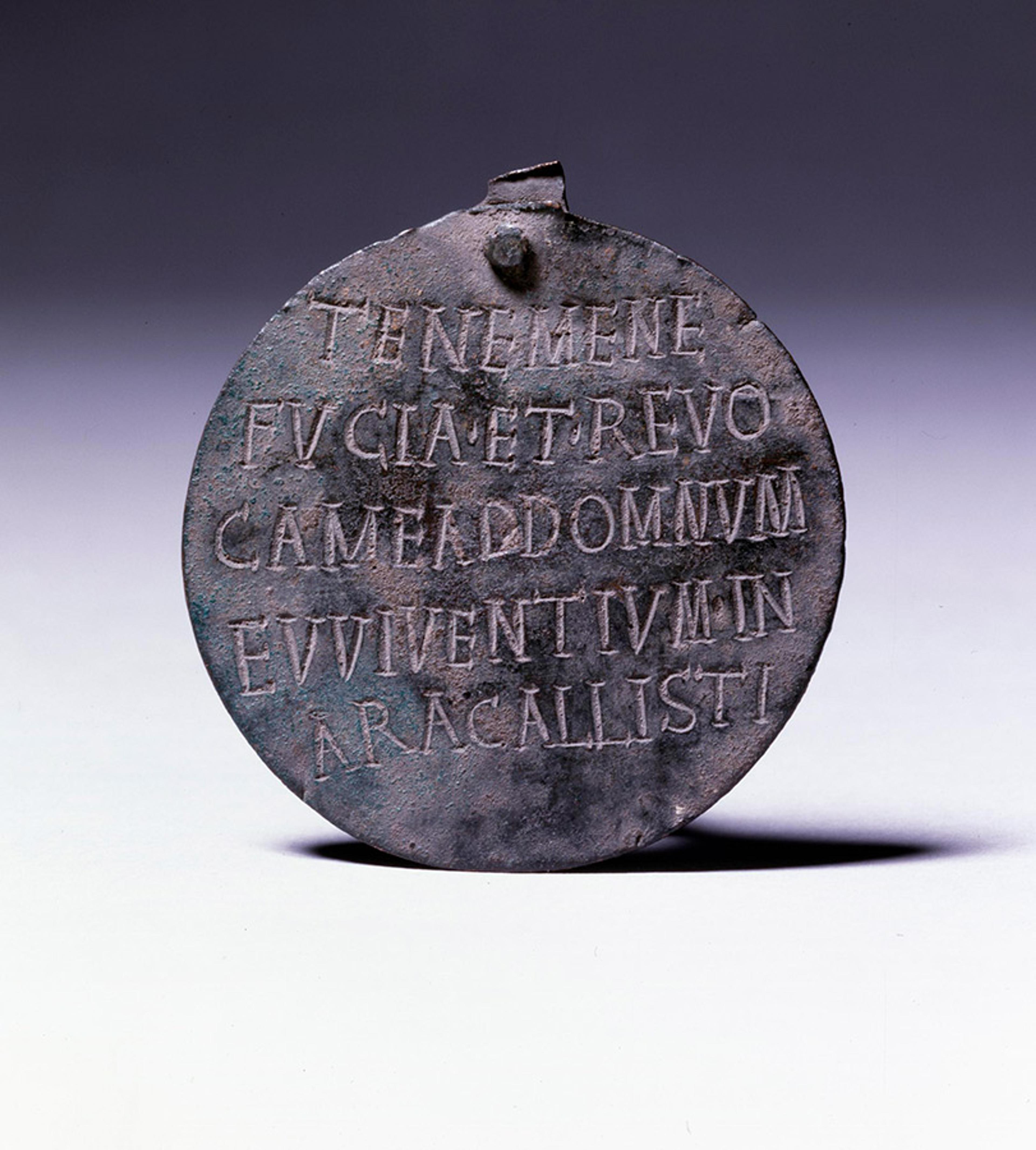

Copper alloy tag that was attached to the collar of an enslaved person, inscribed with a demand to return the wearer to the slave master at his estate in Rome, 4th century CE. Courtesy the British Museum

There are some 45 known slave collars. Many mention the name, occupation and location of the slave’s owner, but never the slave. For example, a bronze tag from a slave collar from Rome announced: ‘Hold me because I have run away and return me to the Caelimontium to the house of Elpidius, vir clarissimus, to Bonosus.’ Its other side said: ‘Hold me and return me to the Forum of Mars, to Maximianus the antiquary.’ It seems the tag had been reused. An iron collar from Rome also offers a reward: ‘I have run away; hold me. When you have brought me back to my master Zoninus, you will receive a gold coin.’

So who was Eutychis? Was she a prostitute, an enslaved woman, both or neither? Was she forced into selling herself? Let us think first of her name. Eutychis is a Greek name that roughly translates to ‘fortunate’, and was in use throughout the Greek-speaking world. Although the graffito surely refers to a real person, we don’t know whether it was her real name, or a slave name, or a working name. If she was a free woman working as a prostitute, she may have chosen Eutychis as her pseudonym; if she was a slave, the name may have been given to her by her owner. Renaming a slave with something cheerful and Greek was a common practice of the Romans.

This act of renaming an enslaved person could affect them in various ways. It robbed the enslaved person of a key aspect of their own identity and replaced it with a sometimes cruel name that emphasised their status as property. A slave prostitute named ‘fortunate’ or ‘lucky’ was probably anything but. Another slave in the House of the Vettii was called ‘Eros’ (‘desire’). The graffito that mentions him reads: ‘Eros likes to be sexually passive,’ but it was later scratched out). Nowadays, we might see this as an aspect of coercive control, an ongoing rite of abuse and humiliation. However, renaming could also allow the enslaved person to retain a separate, inner ‘core’ identity linked with their own ‘private’ name. An unhappy possibility is that we know ‘Eutychis’ only by the name her owner gave her, and she remains, in this sense, invisible.

The second part of the graffito stresses Eutychis’ Greekness. Should we read the label of ‘Greek’ simply as a statement of fact, or could it have a different significance? If the graffito were written by her owner or a pimp, then it could be that both the name and the ethnic label were given to increase Eutychis’ appeal by generating a sense of exoticism – although Pompeii had quite a mixed heritage and attracted all kinds of visitors. Were Greek women fetishised as sex objects by some Pompeiian males? The fetishisation and sexualisation of groups of women (and men), based on ethnicity or race, is well known still, so it is not impossible.

A prostitute would have had to appear cheerful, coy or aroused, depending on the circumstances

On the other hand, perhaps ‘a Greek lass’ would have appealed to Greeks travelling through the town or Greek-heritage Pompeiians, such as Mousaios or Epagathus, named in graffiti from the Lupanar, or Pyrrhus or Chius, known in graffiti from the Basilica at Pompeii. Mousaios’ name was written in Greek rather than Latin, one of a number of Greek graffiti found around the city. Either way, the choice and statement of both her name and ethnicity could have been deliberate business strategies rather than factual biographical details.

The advert also stresses Eutychis’ ‘sweet ways’ (moribus bellis). This is found on a number of graffiti in Pompeii. In the Lupanar, we find ‘Restitua with sweet ways’. Other prostitutes, such as Spes, Successa, and Menander, a man, are so labelled. This label suggests a good time in an indirect fashion, perhaps good company as well as a sexual service. Indeed, in her research on the public and private lives of Pompeian prostitutes, Sarah Levin-Richardson reminds us that prostitution could also involve emotional as well as physical labour. A prostitute would likely have had to run the gamut of emotions, appearing cheerful, coy or aroused, enticing and passionate, pliable or dominant, depending on the circumstances. This contrasts with some of the other graffiti around the town that elaborates on the specific services offered, especially fellatio and sex.

Finally, what of the price of two asses (copper coins)? It seems low; the same price as a loaf of bread. Recorded prices for prostitutes varied, but most tend to be from one to five asses. Two asses seems to have been a common price at Pompeii and may have been a kind of standard low rate. Price could reflect a number of factors. It would be calculated to attract a high volume of customers, or it may reflect the age and perceived appeal of the woman. It could have been used as a punishment. Perhaps there was an element of haggling possible once a punter had expressed an interest. Independent prostitutes may have had little means to protect themselves and enforce payment.

We should also consider what the location of the graffito adds to the story. The text was written on the left wall of the vestibule of the House of the Vettii. The Vettii are usually thought of as brothers, Aulus Vettius Conviva and Aulus Vettius Restitutus, who were freed slaves who took on the name of their former master, Aulus Vettius. Their names were on bronze seals found near a large wooden strongbox in the house, along with a ring with the initials ‘AVC’. In graffiti on the outside of the house, Conviva is named as an Augustalis, a priestly position open to former slaves, while Restitutus urges voters to support one Sabinus. Whether they were brothers, father and son, friends or coworkers can’t really be known, but they seem to have had some wealth and privilege, including their well-decorated town house. The Priapus painting emphasises the Vettii’s wealth, as Priapus was a god of fertility – besides the member and the money, the painting shows his basket of fruit on the ground. Two of the ‘funny’ stories associated with him, related by the poet Ovid, have him failing to rape the goddess Hestia and a nymph called Lotis.

Priapus in the House of the Vettii. Photo courtesy Carole Raddato

The other paintings in the House of the Vettii may tell us more about the life of the house and its inhabitants, and shed light on Eutychis. One careful analysis by Beth Severy-Hoven focuses in particular on the sets of paintings found in a pair of reception rooms, called ‘n’ and ‘p’. The rooms and their decorative scheme seem to mirror each other. Room n has two violent paintings. On the back wall is a depiction of the punishment of Pentheus, who was killed by the female worshippers of Dionysus. The naked Pentheus is falling, arms spread wide as the women attack him from all sides. On the wall on the right, the punishment of Dirce is shown. She is tied, naked, under a bull to be trampled to death, a fate she had planned for another woman, Antiope.

From the House of the Vettii: The Punishment of Pentheus. Courtesy Wikipedia

The Punishment of Dirce. Courtesy Wikipedia

Room p shows the punishment of Ixion at the back, who was tied to a fiery wheel for eternity for trying to rape Hera, and the punishment of Pasiphae, made (for her husband’s crimes) to lust after a bull, on the left. Each room, then, shows the torture of a female and a male character from mythology. Those in room n were punished by humans, and those in p by the gods.

Severy-Hoven argues that we can read the decoration from the perspective of the Vettii being freed slaves and from a perspective of power. As we already noted, enslaved people were there to be used sexually and were likely to be punished in numerous ways, which may have been something the Vettii themselves experienced. The Vettii’s choice of these images of punisher and punished to decorate their public dining rooms would call to mind the distinction between master and slave – both for themselves and for their slaves. As Severy-Hoven puts it: ‘When the owner selected these images of eroticised torture, he was inscribing his own power to punish or to enjoy onto his very walls.’

Was Eutychis a house-slave of the Vettii? It is possible. One clue from that graffito itself is that it may first have read ‘verna’ rather than ‘Graeca’ – that is ‘homeborn slave’ rather than ‘Greek lass’. If she was, it is not unlikely that she would have been a target of sexual advances by the Vettii and their friends. Did the Vettii also pimp out their house slave Eutychis? One ancient novel, The Golden Ass by Apuleius, tells of a young woman called Charite, who has been kidnapped by bandits. When she is caught trying to escape, one of the bandits suggests selling her to a brothel or to pimps in a nearby town. As he says to the bandits, ‘seeing her servicing men in a whorehouse will be sweet revenge for you’. Sex in various ways could be a punishment. Daily life as a slave in the House of the Vettii may have been a constant fight to remain unmolested and unpunished, a fight to retain a degree of control and dignity.

The house may have been home to Eutychis, but it was no brothel like the Lupanar. However, one thing that has puzzled scholars about the House of the Vettii is the existence of a little room behind and only accessible from the kitchen, known as x1. This room is of interest because it is decorated with three large erotic paintings, yet it is hidden away in a service area. Was this the place where Eutychis had sex with customers, making more money on the side for the Vettii? It is possible, but such an activity might not have benefitted the owner’s public reputation. Or were the paintings a gift to a good cook or other slave, who had the use of the room? Alternatively, were they a reminder to the enslaved staff, who may have slept there, of their sexual availability and vulnerability and their lack of power in the house? Another idea is that such rooms, of which there are perhaps six at Pompeii, were private ‘sex clubs’, rooms that conjured up the brothel atmosphere but were not open to the public. Perhaps Eutychis was required to serve her masters in this grim fantasy.

On the other hand, was the Eutychis graffito a real advert at all? We can’t rule out the possibility that it was simply a malicious daubing, in a way familiar from subway graffiti today. The Greek satirical writer Lucian, writing in his Dialogues of the Courtesans in the 2nd century CE, mentioned that graffiti could be used as a joke, to mislead or to stir up trouble between lovers. Maybe Eutychis was a real Greek girl, perhaps even with sweet ways, but she need not have been a prostitute or even a slave. A rejected suitor or jilted lover might have written it in a place that she, and those who knew her, would see it. Perhaps this implies she did have some kind of connection with the House of the Vettii, but we cannot say for certain if she was a house-slave there.

The single graffito we began with has taken us on a journey through some of the darker aspects of life in Pompeii: the grittiness of the Lupanar, the ever-present threat for the enslaved of sexual assault and violence, being chained to the floor of a basement in pain and terror, being owned and being used. It is difficult to conjure these horrors while visiting the sun-baked town with its busloads of bright-shirted and good-natured tourists, or marvelling at the beautiful art and architecture in glossy books. We will never really know for sure about Eutychis, beyond the fact that there was a woman attached to the name. We may never know what life in the House of the Vettii was really like for its inhabitants, either. But we can keep trying to read the evidence to find the stories that bring the lives of Pompeii’s less fortunate into the light.