This feather belonged to a Canada goose that summered in Labrador and migrated along the Atlantic flyway, to winter somewhere in New Jersey most likely. On a cold winter afternoon, 15 January 2009, the goose was flying with a skein of conspecifics at about 3,000 feet. Just as it was passing over the Bronx, the goose – and many of its colleagues – collided with an airplane that had taken off from LaGuardia Airport minutes before. This particular goose was ‘ingested’ by the left engine, leading to catastrophic failure. A similar drama unfolded in the right engine, and so the plane was forced to land in the Hudson River. All the humans were fortunate to survive. It was a ‘Miracle on the Hudson’.

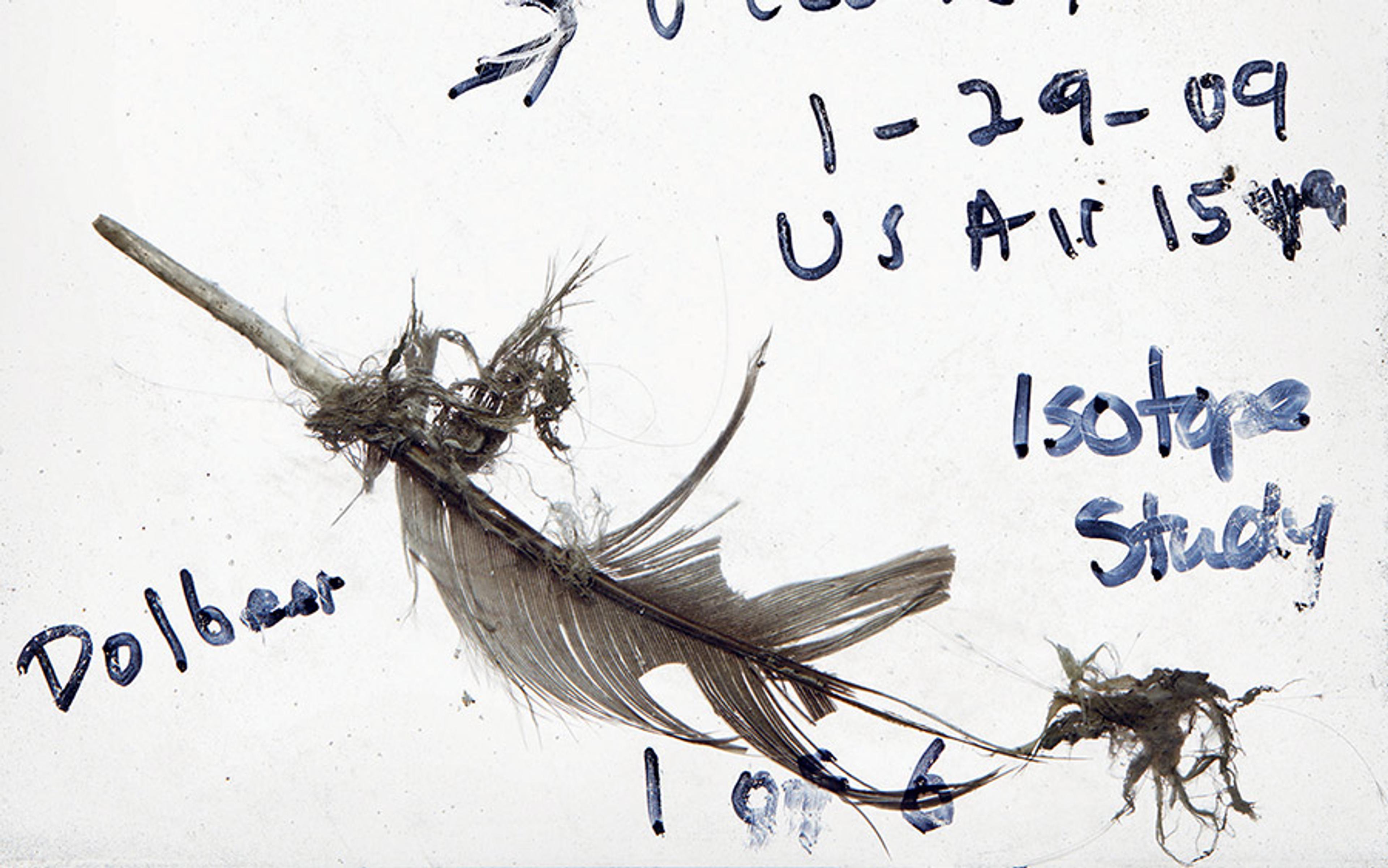

Feather belonging to a goose ingested through the engine of US Airways Flight 1549, the so-called ‘Miracle on the Hudson’. Photo by Tim Flach

Richard Dolbeer, a science adviser for Wildlife Services at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), was on the team that investigated the plane once it had been drawn out of the river. There is no bigger name in the world of bird-strike mitigation than Dolbeer’s; the drama of the event required the investigative power of a seasoned expert. He scraped what was left of the goose from the left engine’s outer flowpath, put it in a plastic bag – designed for just such a purpose – made some notes on the bag, and sent it to the Feather Identification Lab at the Smithsonian Institution. The naturalists at the lab quickly identified the species, Branta canadensis, notified the US National Transportation Safety Board, and placed the bag into a storage facility in Suitland, Maryland. Those same naturalists were responsible, some years earlier, for coining the term ‘snarge’. Snarge is the avian tissue that’s left over after a bird-strike. It’s a horrible word that onomatopoeically conveys the peculiarly destructive violence of acceleration in the Anthropocene.

If we extrapolate beyond the case of birds and planes, snarge can more helpfully be used as a way to characterise all collisions between forms of fossil-fuel-based human mobility and solar-based animal mobility. Thus, snarge is the sum total of all the dead or decaying tissue left over when plane hits bird, car hits mammal, boat hits manatee, ship hits whale, train hits cattle or elephant, and so on. It’s difficult to calculate the biomass of snarge, though many have tried. We can say, with some degree of certainty, that in the US alone between 1 and 2 million deer are snarged annually. They are among the very rough approximation of 365 million vertebrates – including 21 species that are threatened or endangered – who fall victim to automobile traffic in the US. This annual number of snarged animals also includes 1.2 million dogs, 5.4 million cats, and between 4,000 and 5,000 humans. Planes in the US strike more than 13,000 birds per year, according to a report by the Federal Aviation Administration. While shipstrikes are notoriously difficult to quantify, it seems reasonable to say that every year at least ten whale deaths are caused by colliding with ships moving through North American waters and between 80 and 100 manatees meet their end by Floridian propellers. Cumulatively, these organisms represent a collection of animals that occupy, as Roger Knutson wrote in his field guide Flattened Fauna (1987; 2006), ‘a habitat almost unique to the 20th century … Fast cars and hard-surfaced roads have produced the entire flattened fauna described here in less than an eye-blink of evolutionary time.’

Knutson, a biologist, perceptively put his finger on the issue of novel habitats. Creatures that are vulnerable to become snarge move, live and die in Anthropocenic environments that are largely designed to accelerate industrialised human beings and their goods. Highways and their right-of-ways have been designed for the speed and safety of automobile and truck traffic, but they are also edge habitats that bring animals out of the forest. Airports contain wide swathes of grassland that provide suitable browse and protection for birds, ducks and geese. Dredged canals in Florida provide wonderful habitat for manatees. After heavy snows, Alaskan elk sometimes use cleared railroad tracks to move over the landscape. All of these environments are designed and managed for the safe acceleration of industrialised humans. Like so much of the Anthropocene, they are built environments, infrastructures, naturecultures, hybrid spaces, landscapes, designer ecosystems.

These ‘transit-ecological systems’ have largely been designed by civil and traffic engineers. They are ruled by a paradigm that couples speed with safety – the protection of both efficiency and human bodies. The plants, trees, sedges and grass used in landscaping support that paradigm. Nevertheless, they are, using the phrasing of Emma Marris’s similarly-named book, the ‘rambunctious gardeners’ of modernity. They are joined by departments of transportation who actively maintain these habitats. They produce reports, studies and guides – new forms of knowledge and expertise that govern the management of a significant portion of the globe’s overall land use. What species of grass are best to plant? What kinds of pesticides and herbicides should be used? When to mow, how high to mow, invasive or – with seldom-noticed irony – native species?

These moving parts – wildlife, infrastructural environments, the people and technologies that travel through them, and the people who design, study, and maintain them – cumulatively make up a kind of ‘snarge matrix’. It would certainly be fair to call this world by more familiar terms – transportation network or infrastructure – but ‘snarge matrix’ highlights the unintended but nevertheless designed death of animal lives. Most of us spend little time thinking about the snarge matrix, which is a missed opportunity. Snarge thinking helps us to understand the new relationships between humans and nonhuman animals cohabiting the Anthropocene. Thinking about snarge is unpleasant, and the pervasiveness of the problem tends to lead one to despair. But if we listen carefully, snarge can tell us something that might be helpful to figuring our way out of, or perhaps just coming to terms with, the Anthropocene.

At its essence, snarge represents the completely irreconcilable conflict between two different forms of mobility. One form we simply call ‘animobility’, a helpful term used by the sociologist Mike Michael at the University of Exeter, which refers to motions that are fuelled directly by Sun and muscle, and are the results of millions of years of evolutionary history. The newer form of motion harnesses fossilised sunlight from millions of years ago and allows a rapid acceleration of industrialised human beings. In the blink of an evolutionary eye, this acceleration makes snarge possible and even inevitable.

Anthropocenic forces have dramatically transformed the lives of nonhuman animals. For our purpose here, snarging created a new form of killing that is without historical precedent and with few contemporary analogues. With some regrettable exceptions, snarge is a form of death that is almost always already an ‘accident’. Like ocean ‘by-catch’ or mowing over a family of corncrakes, death-by-vehicle is unintentional, a byproduct of acceleration. And it has become, more or less, an acceptable form of killing. That is, we do not hold the driver of a car morally or legally culpable for accidentally killing a deer, and with good reason. A driver has no intention of killing. But it is still a kind of killing that calls for a thoughtful response. Now, it would be wrong to imagine that life can exist without participating in some forms of killing, but as Donna Haraway notes in When Species Meet (2007), members of a thoughtful species should consign themselves to becoming thoughtful killers. Snarge rarely registers on our moral radar, probably because the agent of killing – mass acceleration – is structurally baked into almost everything we do. This is a peculiar malady of the Anthropocene; by participating in an accelerated mode of life, we have involuntarily become thoughtless killers of wildlife.

It is tempting to think about the ways that animals have responded to this new form of killing. We know, for instance, that some moose rear their young close to highway environments infrequently visited by predators that are presumably scared off by the sound of traffic. We also know that some species of wildlife accommodate their daily movements to highways. And snarging has selective power with a corresponding evolutionary effect; we think that cliff swallows in western Nebraska might have developed shorter wings to dodge traffic. These are stories of animal agency, and there is virtue in knowing them, but such knowledge gets us only so far. Since the key tenet of Anthropocenic thinking is that industrialised humans have exercised Earth-systems-changing agency over the past 200 years, any normative thinking needs to start and end with a deeper understanding of human agency.

The cattleguard and the cowcatcher create an infrastructure that erases animals from the landscape

The dominant human response by both transportation and natural resource agencies has been to mitigate the damage. Indeed, the field of ‘animal-hazard mitigation’ – a form of wildlife management that, again, is uniquely Anthropocenic – is big business. Similar to bounties placed on wolves and coyotes, this form of management codes wildlife as a hazard to accelerated humans – an accidental problem in need of mitigation. And so the prevailing paradigm has been to harden the infrastructure, to make the snarge matrix impervious to animals, to clear infrastructure of wildlife that gets in the way. For instance, the ‘zero tolerance policy’ for geese around JFK, LaGuardia and Newark international airports has led to a contract with the USDA’s Wildlife Services that routinely culls thousands of resident Canada geese – not, incidentally, the migratory fowl that brought down Flight 1549 – from the municipal landscape.

There are infrequent moments when the discourse of mitigation flips, as with the case of certain endangered species. When it was learned that motor traffic presented the largest threat to the endangered Florida panther, a highway was engineered – under the mandate of the Environmental Species Act of 1973 – to harden the Interstate and mitigate the damage to an endangered species. This was successful for animals around the I-75, but less helpful for the panthers navigating the sprawling road system of southwestern Florida.

Mitigation seems like a logical response to the snarge matrix, but it is limited and partial in two related ways. First, it does not grapple with the fundamentally irreconcilable conflict between animobility and the movements of accelerated humans. The discourse of mitigation almost always prioritises movements accelerated by fossil fuels. Second, mitigation is steeped in a refusal to accept transit-ecological systems as hybrid landscapes. This is the dream of impermeability, which can be conceived of as the inverse of the US wilderness ideology. If our post-frontier desire for wilderness can be characterised by the dogged erasure of humans from the landscape, then the invention of the railroad cattleguard and the cowcatcher show exactly the opposite desire – an attempt to create an infrastructure that erases animals from the landscape. In this sense, William Cronon’s important critique of wilderness as nonhuman must be matched with equal force by a critique of the right-of-way as only human.

If we accept that the snarge matrix calls for a moral response, and that our response so far has been inadequate, then we might try to search for historical and contemporary solutions for living in or beyond the Anthropocene. Indeed, there are other stories, more humane stories, that snarge can tell us. One healthy response might be to apologise, as Barry Lopez does in his brief recounting of a car trip from Oregon to South Bend, Indiana. Apologia (1997) is an unconventional travel narrative. Whenever he encounters roadkill, he stops to move the carcass deep into the right-of-way: ‘The ones you give some semblance of burial, to whom you offer an apology, may have been like seers in a parallel culture. It is an act of respect, a technique of awareness.’

Others have apologised through art, poetry and activism. Some apologists find ways to literally mend the broken bodies and turtle shells that litter the right-of-way. For instance, wildlife rehabilitation clinics around the world attempt to administer care to the casualties of the Anthropocene. These are all important responses that speak to a sometimes conscious ambivalence or critique of an accelerated lifestyle. Living in the snarge matrix comes with guilt. Therapeutic wisdom to the contrary, guilt is a powerful human emotion, and a necessary first step to healing the wounds of the Anthropocene. We must understand that getting in a car, plane or train, that ordering a book from Amazon – all are destructive acts that create snarge. Wildlife deserves an apology.

But it’s important to move beyond an apologetics of roadkill. It is possible to create and recreate infrastructure that is less deadly to wildlife. Taking its cue from European and Canadian landscape ecologists, the new school of ‘road ecology’ is beginning to conceive of highway infrastructure as part of the ecosystem dynamics of the wider landscape. From this light, a road can be a little like a river – part of an ecosystem that has a barrier effect but can also be a mechanism for channelling the flow of energy, water, nutrients and animals. A good example of this idea in practice is a 50-mile stretch of US Route 93 in western Montana. After a long period of conflict pitting the Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) against the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Indian Reservation, MDT created a permeable highway with culverts, underpasses and overpasses that balances the imperative for human acceleration with animobility.

When landscape architects, environmentalists, wildlife biologists, corridor ecologists, community advocates and transportation experts sit at the same table to redesign a road, something interesting can happen. Through a more civil civil engineering, the snarge matrix can be more thoughtfully redesigned. This, at first glance, seems like an expensive undertaking but advocates of permeability point to our crumbling infrastructure. If bridges and overpasses need to be rebuilt, they ask, why not rebuild them as corridors that reconnect previously fragmented habitats? Our transportation infrastructure is the greatest cause and symbol of life in the Anthropocene; working our way out of the Anthropocene requires a new infrastructure.

Thoughtful design can lessen the destruction caused by accelerated humans, but there really is only one surefire solution to the problem of these conflicting mobilities – the deceleration of industrialised humans. Ivan Illich, the Austrian Catholic priest and social critic, made this argument in his Energy and Equity (1974). Illich was less concerned with snarge than he was with the impoverishment of the global South and the role that energy consumption played in perpetuating inequality. All societies can benefit, he argued, by increasing their consumption (their speed) up to a discrete point. Beyond that point, social relations degrade, and power and capital pool into the hands of a small group of technocrats. In an argument that was prescient of Pope Francis’s recent encyclical, Illich called for the industrial world to slow down, to wean itself from an increasing consumption of energy in the interests of global equity. The top speed of a modern bicycle would suffice. Of course, the opposite has happened. Since Illich’s time, the portion of humanity enjoying the fruits of acceleration has increased in number as developing nations adopt the mobility patterns of overdeveloped peoples. The virtue of slowness seems like an impossible dream.

Snarge is an indictment of acceleration and of the very process of becoming comfortable with structural violence

But there are stories that highlight the possibilities of a decelerated world. The creation of no-wake zones in south Florida’s canals and lakes provides some respite for the glacially slow movement of the Florida manatee. And an energetic lobbying group of scientists and conservationists has been able to decelerate the pace of global shipping traffic. In the interest of the endangered North Atlantic right whale, they have convinced the International Maritime Organization to shift shipping lanes away from critical right-whale habitat and, even more surprising, they have created seasonal speed limits for large ships that have no choice but to share their sea lanes with whales in what some conservationists call ‘the urban ocean’. Even more inspiring stories come from outside the US. Rajkumar Devaraje Urs of the Wildlife Conservation Foundation has recently been able to completely halt night traffic along several highways that move through the Bandipur Tiger Reserve outside Mysore in India. And the UK-based nonprofit Froglife mobilises children to safely slow down car traffic that threatens amphibians and reptiles crossing British roads.

These are small but significant countercurrents. And on some level, they have much in common with other environmental movements currently in fashion: the slow-food movement, initiatives for walkable and sustainable cities, car-sharing, and the down-shift movement, to name a few. Indeed, some travel authorities believe that we have hit the point of ‘peak travel’. Accelerated humans might be growing travel-weary, and we could have saturated our desires and technologies of acceleration. Moreover, the US National Complete Streets Coalition has highlighted the problem of hugely disproportionate pedestrian deaths and injuries among people of colour in many US cities. They are reframing the issue of sustainability as a movement of social justice. In a cruel irony, a movement that began with a bus boycott continues to play out, but this time we are denying public transportation to our most at-risk citizens so they can fend for themselves on the streets, in a not-too-distant future, filled with driverless cars. The critique of mass acceleration is becoming de rigueur.

But we knew this already. How does thinking about snarge add to the discussion of the Anthropocene? And aren’t there more important things to worry about? Of course. But thinking about snarge has three particular virtues. First, it aims our focus at the root cause of Anthropocenic climate change – an accelerated mode of existence that is impossible without fossil fuels. Indeed, I might amend Aldo Leopold’s land ethic of 1949: ‘A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community.’ It is wrong, Illich and I would argue, when it moves faster than the speed of a bicycle. If we found ways to eliminate inefficient acceleration, we would lessen the snarged victims of the world, but there would also be some obvious beneficial cascading effects.

Second, snarge is a reminder of how quickly industrialised humans accommodate to, and normalise, Anthropocenic change. Roadkill, like pedestrian deaths, were a source of moral outrage in the 1920s when automobiles began roaming the industrialised world en masse. But then we just got used to it. Roadkill became an acceptable – no matter how regrettable – casualty of modern life. Snarge needs to be an uncomfortable reminder of that shifting baseline, an indictment not only of acceleration but of the very process of becoming comfortable with structural violence. Finally, thinking about snarge is a powerful reminder that despite the many intellectual countermovements to animalise Homo sapiens – evolution, the id, sociobiology, deep ecology, biocentrism, ecocentrism, and so on – accelerated humans wield a terrifying power that distinguishes us from the experiments of the living.

The Anthropocene is less a geological epoch than it is a story, and that is why journalists and scholars in the humanities and the social sciences have been so eager to embrace – or at least tangle with – the concept. Thinking about snarge leads to experimenting with new stories – stories about the virtues of slowness, of moving our bodies and our goods in a more just and humane rhythm. The moral of snarge’s story is not, to be clear, about the virtue of stasis. Rather, it is just another iteration of the stories of Icarus, Prometheus, Frankenstein, Dr Strangelove, the Tortoise and the Hare. Think about it this way. There are those among us who will go out of their way to run over a tortoise crossing a road, and there are others who swerve out of the way to avoid the tortoise, and then there are those who get out of their cars to help the tortoise to safety. These are all Anthropocenic responses. Snarge would have us selling our cars and taking the bus.

This essay is an edited extract from the book ‘Future Remains: A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene’ (2018), edited by Gregg Mitman, Marco Armiero and Robert S Emmett, and published by University Chicago Press.