Listen to this essay

21 minute listen

With its enchanting glow and its mysterious darkness, the Moon has been a deep and abiding symbol for many people from around the world. This was as true for the medieval period as it is today. As they gazed on or imagined the Moon, many medieval creators and audiences were mesmerised by its beautiful and enigmatic nature, and they wondered what the Moon might represent.

The Madonna of Humility (c1390) by Lippo di Dalmasio. Courtesy the National Gallery, London

Given the Moon’s strange and ethereal nature, it is not surprising that it features heavily in religious symbolism across a range of traditions. What is surprising is the way it was used, in very versatile and at times radical ways. Despite its association with inconstancy and fragility across a range of cultures, we also find it used to convey immense power. Here I want to focus on the Moon’s symbolic potency in two very different medieval religious traditions, medieval Christianity and medieval Islam.

First, a note on definitions. I use the term ‘medieval’ to cover the years from c500 CE to c1500 CE, but the term can be problematic. For example, ‘medieval’ is itself a Western word that we should apply to non-Western cultures with some caution. What might constitute the ‘medieval’ period also varies from culture to culture.

In addition, we could use a reference book like Signs and Symbols: An Illustrated Guide to Their Origins and Meanings (2008; 2019), and say that a symbol ‘is a visual image or sign representing an idea – a deeper indicator of a universal truth.’ In the medieval world just as today, the Moon could stand for much more than itself: it could be used to signify complex ideas or teachings, or to indicate momentous historical events. There is a long history of treating the Moon, and the other celestial bodies, in a ‘semiological’ way – as signs rather than causes of events on Earth, though the Moon was often believed to be a cause of events too. In the ‘semiological’ approach, the Moon becomes a text to be read and deciphered. It holds profound meaning, and it is for human beings to interpret it.

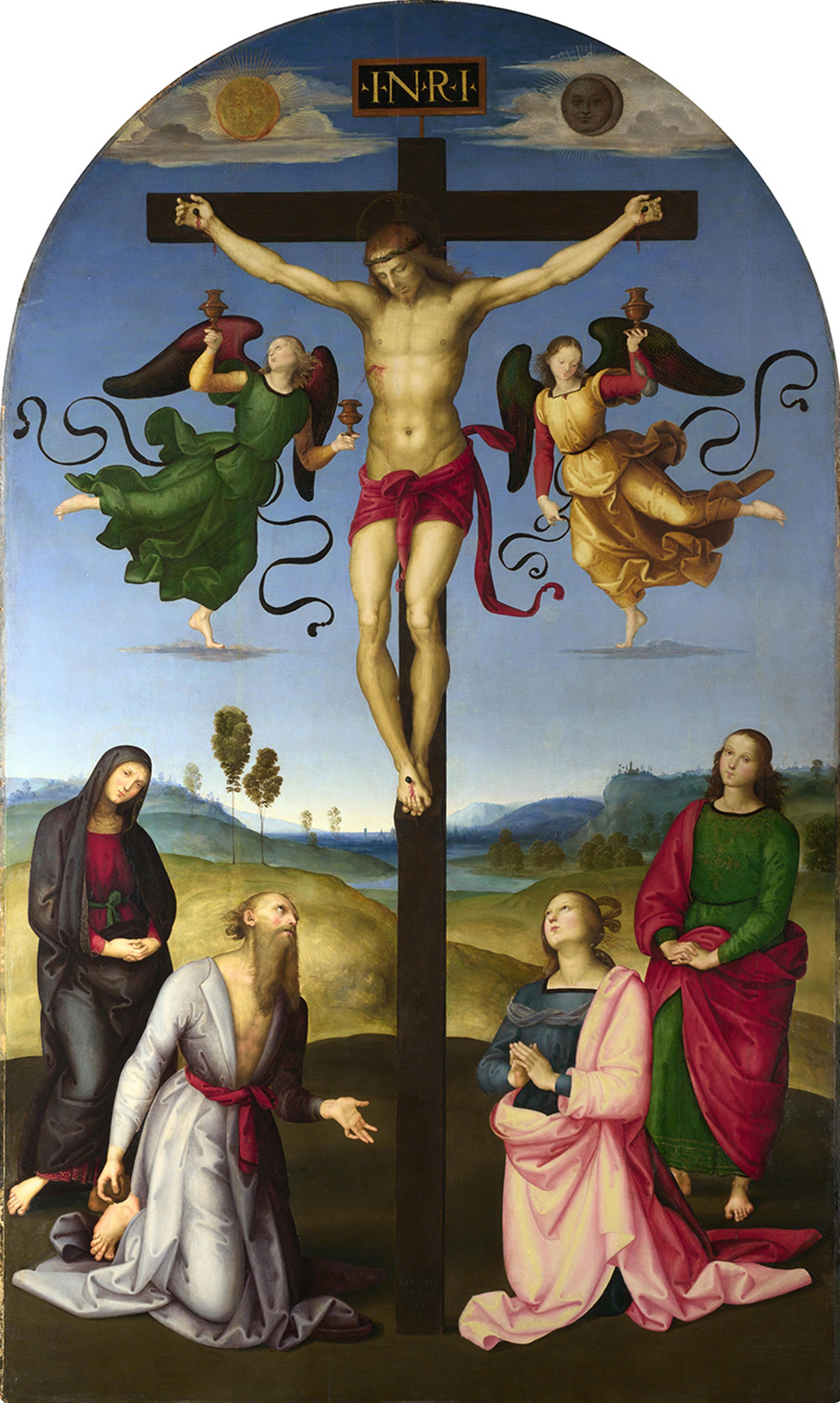

We see Earth below Christ’s feet, and above him the Sun and the Moon, showing Christ’s command over Creation

At the simplest and most straightforward level, the Moon emerges in art and poetry as a way of indicating the workings of the Divine within Creation. For example, the Moon appears in scenes representing vital stories in Christian history, emitting its glow at crucial moments of the Christian salvation narrative. The Moon features in many scenes of the Passion of Christ and of the Last Judgement, where it accompanies the Sun. Here, Moon and Sun together serve to show the deep and reverberating cosmic significance of these moments in Christian history. Examples of such illustrations include the Crucifixion scenes in the Book of Pericopes (a book of biblical passages) and the Sacramentary (a book of liturgical excerpts) for King Henry II in the 12th century.

The ceiling of the chancel of St Mary’s Church in Kempley, Gloucestershire, England. Courtesy English Heritage

When it comes to Last Judgement scenes, one powerful example is found in a wall painting in the chancel of St Mary’s Church in Kempley in Gloucestershire, England, which dates back to c1120. In this image, Christ is enclosed in a lobed mandorla – an oval-shaped aureola – holding a book or tablet with the Greek monogram initials IHC and XPS, indicating his name. We see Earth below Christ’s feet (echoing Matthew 5:35: ‘Nor by the earth, for it is his footstool’), and above him radiate the Sun and the Moon, showing Christ’s command over the entirety of Creation. In this example as in many other Last Judgement scenes, the Moon is part of a deep symbology that represents the fullness of Creation answering to Divine power.

A medieval depiction of Doom in the chancel arch of St Mary the Virgin at Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire, England. Christ is shown sitting in judgement, to his left is the Sun and to his right the Moon. Courtesy St Mary the Virgin Church

And yet, the Moon did not simply appear in Christian iconographic scenes to show Divinity within Creation. Often, it was also a symbol with political import, used to convey hegemonic institutions and, in doing so, to establish complex power relations.

The Moon emerges in the concept of ‘hierocracy’: the supremacy of the Pope over the emperor. In this symbolism, whereas the papacy is the light-giving Sun, the state is only the Moon, merely reflecting the Sun’s glowing light. In a letter to the prefect Acerbius and the nobles of Tuscany (dated to 1198), Pope Innocent III writes:

Just as the founder of the universe established two great lights in the firmament of heaven, the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night, so too he set two great dignities in the firmament of the universal church …, the greater one to rule the day, that is, souls, and the lesser to rule the night, that is, bodies. These dignities are the papal authority and the royal power. Now just as the Moon derives its light from the Sun and is indeed lower than it in quantity and quality, in position and in power, so too the royal power derives the splendour of its dignity from the pontifical authority …

(Translation from Medieval Sourcebook, 2025)

The Moon, then, could also function as a symbol that provided a powerful and memorable image in political and legal arguments about the superiority of the Pope.

The Moon’s supposed inferiority to the Sun conveys the relative importance of a human institution

But, rather than the papacy being represented by the Sun and royal power by the Moon, it was in fact much more common for the Church itself to be symbolised by the Moon. This occurs in the Glossa Ordinaria (‘Ordinary Gloss’), for example, a large compendium of biblical interpretations, and in works by many other ancient and medieval authors. These authors include Ambrose of Milan (c339-397), Augustine of Hippo (354-430), Isidore of Seville (c560-636), the Venerable Bede (673-735), Rabanus Maurus (c784-856), Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) and Peter Lombard (c1100-1160), among others.

The Church Father Augustine of Hippo puts forward two possible ways in which the Church can appropriately be understood as the Moon, depending on whether people believed the Moon generated its own light, or whether they believed it reflected the light of the Sun. If the Moon generates its own light, says Augustine, then like the Church it has both a ‘light’ side and a ‘dark’ side: the Church has a spiritual (‘light’) side and a carnal (‘dark’) side. In the Patrologia Latina, a 19th-century collection of the writings of the Church Fathers, we read that if the Moon reflects only the light of the Sun, then it is like the Church because the latter is illuminated by Christ, the one true Sun. In accordance with this second reading, the Venerable Bede, for example, says that Christ ‘illuminates the Church, just as the Moon is said to receive light from the Sun’. (Translation my own).

So, in these examples, the Moon does not show Divine creativity only within the cosmos. Instead, it has an urgent and very Earthly significance, used to demonstrate and navigate intricate power relations: on the one hand, between papacy and state; and on the other, between the Church and the Divine. In both cases, the Moon’s supposed inferiority to the Sun conveys the relative importance of a human institution.

Further to this, the Moon is also compared with the Sun in a very different and pressing way: to navigate the distinction between Christ’s humanity and divinity. In an English sermon for the Sunday before Lent (‘Quinquagesima Sunday’), associated with the Wycliffites, or the followers of John Wycliffe (c1328-1384), the Moon represents Christ’s humanity:

Jericho is the ‘Moon’ or the ‘smelling’ that men should have, for each man in this life should smell Christ and see him; and just as the Moon is the principal planet after the Sun, so is Christ’s manhood the principal after his Godhead. And as fathers of the old law smelt Christ in their deeds, so much more should we now smell Christ in all our deeds; and then we should see this Moon, and end securely in this way.

(Translation my own)

This sermon appeals to two meanings of ‘Jericho’ in Hebrew: fragrance, and the Moon. Following the work of the ancient scientist Ptolemy (c100 to 160s-170s CE), medieval astronomers understood the Moon to be a planet: in ascending order from Earth, the planets were the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. A distinction is made here between the Moon of Christ’s humanity, and the Sun of his Divinity – reminding us of the Church-Moon/Divine-Sun distinction we witnessed earlier. But the Moon is still invoked to represent something of tremendous significance: the very humanity of Christ himself.

With its centrality to power relations, the Moon has shown itself to be a compelling symbol – and potentially even a dangerous one, when taken to assert the authority of one institution over another. As we turn to Islam, we find the Moon associated intimately with the Prophet Muhammad and even God himself. In this association, the Moon is linked both to Allah and to God’s dignitaries on Earth, and the central role these latter individuals play in propagating religious belief.

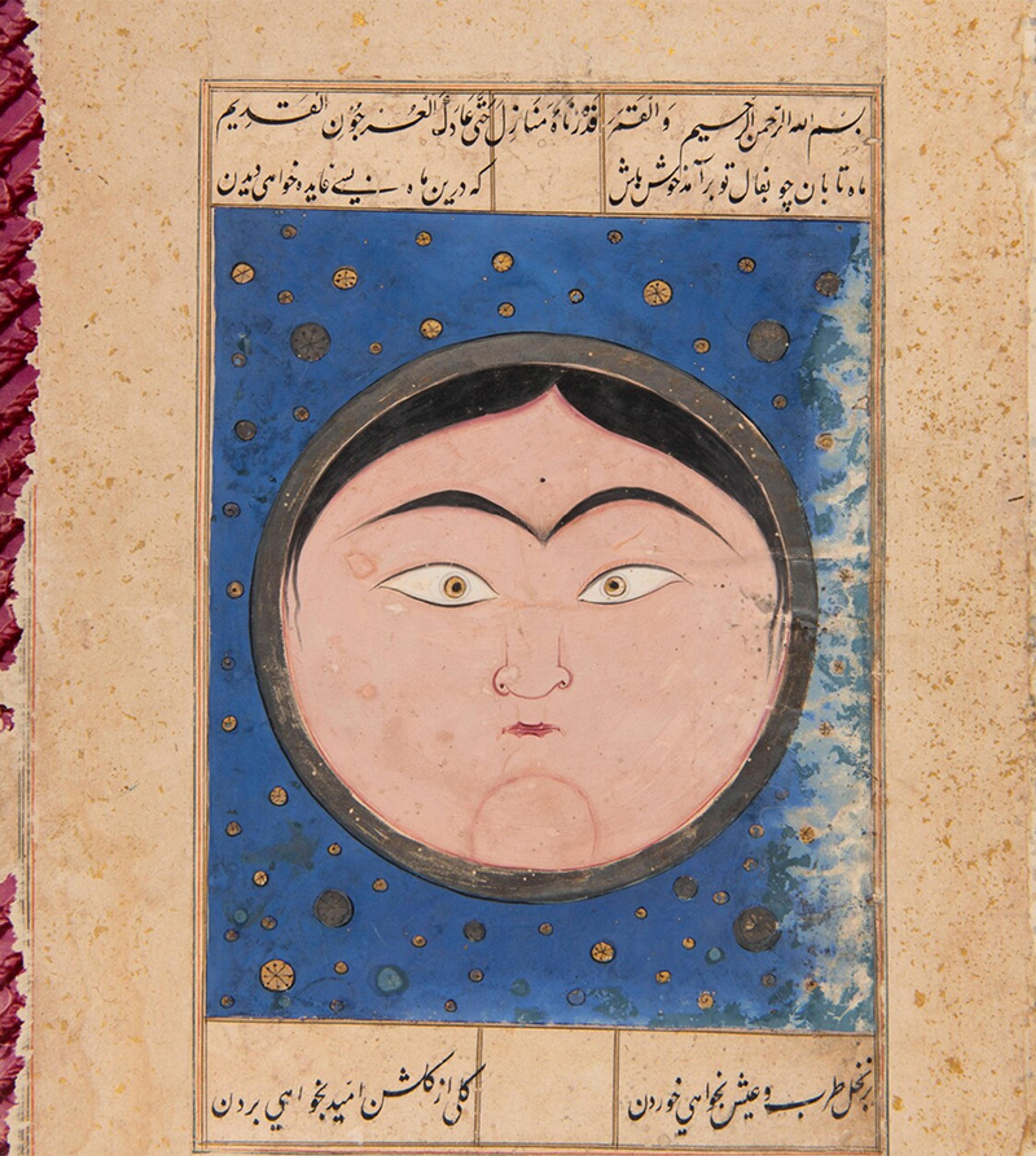

A depiction of the Moon from a 16th-century Falnama, a Persian book of prophecies. Courtesy the Wereld Museum, Leiden

The Moon appears in the writings of medieval Islamic ‘mystics’, or Sufis (though there are difficulties with defining Sufism as the ‘mystical’ branch of Islam, as Lloyd Ridgeon writes on medieval Sufism). One medieval Sufi poet was ʿAṭṭār of Nishapur (1145-1221), who wrote many poems in Persian. His works include his allegorical poem The Conference of the Birds, in which the birds of the world seek their king, the legendary Simorgh; it is an allegory of the soul’s quest to find and become one with the Divine. For ʿAṭṭār, the Moon itself is part of a cosmos that is in a state of profound yearning for the Divine. Such is the Moon’s desperate personified longing that it even changes shape – moving through gibbous and crescent forms – in its love. In ʿAṭṭār’s image, humanity becomes associated with the Moon, the entire cosmos caught in this inescapable desire to draw closer to the Divine.

But a particularly important mortal is associated with the Moon: the Prophet Muhammad himself. In the most direct terms, he is said to be like the Moon: in The Conference of the Birds, ʿAṭṭār likens the Prophet to the Moon in beauty and splendour. Beyond this, in Islamic tradition the Prophet himself caused a potent miracle of the Moon. Islam has an entire surah (Chapter 54) of the Quran called ‘Al-Qamar’ (‘The Moon’). This surah begins by detailing the miracle involving the Moon: the Prophet Muhammad performed a miracle that caused the Moon to split into two. This miracle is known as shaqq al-Qamar (the splitting of the Moon). The surah opens: ‘The Hour draws near; the Moon is split. Yet whenever the disbelievers see a sign, they turn away and say: “Same old sorcery!”’

The Moon becomes about a prophet’s great power as the very messenger of God

Surah 54 is one of the ‘Meccan surahs’ (an earlier surah revealed before Muhammad and his followers made the move to Medina). After its opening lines, which convey the miracle of the splitting of the Moon, the surah then focuses on disbelievers and the punishments they consequently suffered. Examples include Noah’s Ark during the Great Flood, the Ádites who rejected their prophet, the Thamud who rejected their prophet, the Sodomites who rejected Lot, and the Pharaoh and his people who rejected Moses. The initial lines of the surah, on the Moon miracle, form the basis of this meditation on disbelief and its terrible outcomes.

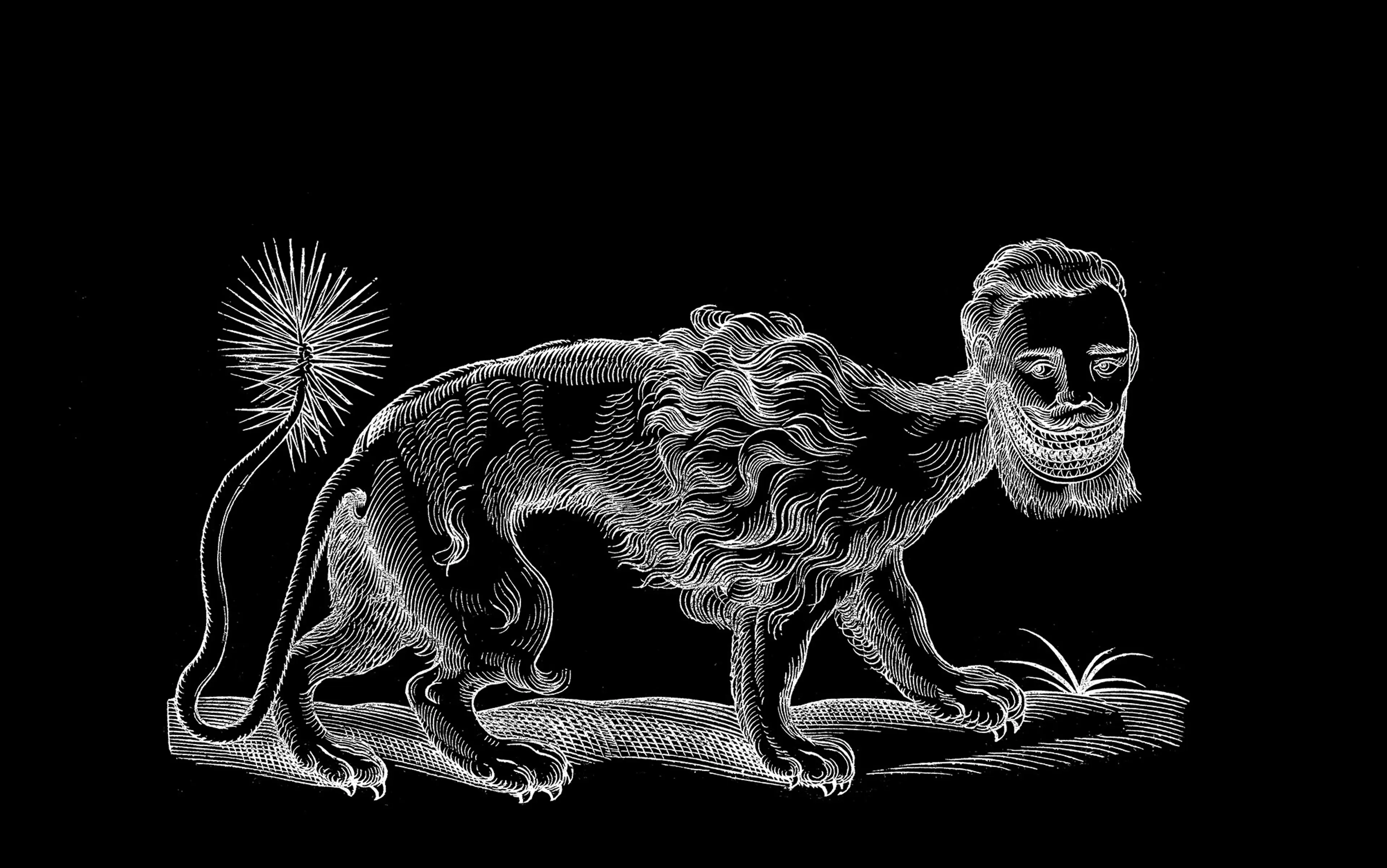

Muhammad splits the Moon. An illustration taken from a 16th-century Falnama. Courtesy SLUB Dresden and Wikipedia

The miracle of the splitting of the Moon has been interpreted in a range of ways. One is the historical reading: that the Prophet Muhammad performed this miracle but the people of Mecca still disbelieved him. Other readings are more eschatological in focus: these readings see the splitting of the Moon as a sign of the Last Judgement. In either case, the Moon becomes about a prophet’s great power as the very messenger of God, in Muhammad’s case as the seal of all prophets (khātim an-nabīyīn or khātim al-anbiyā), a phrase used in the Quran.

Much of this exegesis dates from the medieval period. The Egyptian scholars Jalal al-Dīn al-Mahalli (1389-1459) and Jalal al-Dīn al-Suyuti (1445-1505) interpret the opening of Surah 54 as follows: ‘The Hour has approached means the Day of Judgement [al-Qiyāma] is near. The Moon has split means that it has split into two halves.’ Both authors also say that the ones who reject the sign are ‘the unbelievers of the Quraysh’ (kuffār Quraysh), referring to the Quraysh tribe who lived in Mecca before the rise of Islam. Al-Mahalli and al-Suyuti show evidence of both the historical and the eschatological readings in their exegesis, but in each case emphasise the Moon’s role in communicating prophetic wisdom.

The 15th-century poet Abd ar-Rahman Jami interprets the miracle in a different and more playful way. He employs gematria (the attribution of numerical values to letters) to decode the miracle. The full Moon is the circular letter mīm (م), which has the value of 40. In the split Moon, each half becomes an Arabic letter nūn (ن), which has the value of 50. As such, the Moon increases in value through Muhammad. The real Moon, split through miracle, becomes symbolically more valuable through the miraculous act.

In its association with the Prophet Muhammad, the Moon proves itself to be an all-important symbol, showing the problems, from an Islamic perspective, of disbelief in God’s prophets. The Moon reveals the immensity of Divine power enacted through the prophets themselves. Yet, the Moon can be even more powerful – reaching in fact the greatest position of authority in Islamic contexts.

Even if the Divine remains the ‘Sun’ for Christian authors, we find in Islam an altogether different story. Among Sufi poets, the Moon actually stands in for the Divine himself. The Persian poet Jalāl al-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī (1207-1273) identifies the Moon with the Divine. In one of Rūmī’s poems, the speaker talks about seeing moonlight on a wall. But, the speaker says, we should not then worship the wall simply because of the light we see there. Instead, we should look to the true source of the light: the Moon itself. Thus, humans should not become distracted by the mere reflections of God and end up worshipping Creation itself. Rather than worshipping Creation, which is formed of reflections of the Divine, we should look to the true Illuminator.

Just like this Moon, the Divine does not enter into typical linear patterns of time or into human cognitive frameworks

The Andalusian Sufis Abu al-Ḥasan al-Shushtarī (1212-1269) and Muḥyiddin Ibn ʿArabī (1165-1240) also identify the Divine with the Moon. In two of al-Shushtarī’s poems in the muwashshaḥ form (a type of multilingual strophic poetry developed in Al-Andalus, the Islamic Iberian Peninsula), the speaker says:

Oh night, long or not long, I must watch you;

But if my Moon were with me, I would not remain to watch yours.

(Translation my own)

The meaning here is that the Divine is the best of all Moons – and if the Divine were present with the devotee, the devotee would not need to focus on the Moon of the night.

Both like and unlike al-Shushtarī, Ibn ʿArabī imagines a 14-year-old girl as the Moon (in turn representing the Divine): the number 14 is significant because the full Moon appears on the 14th day of the month according to the Islamic lunar calendar. This girl who is a Moon does not change shape or move through the signs of the zodiac. Just like this Moon, the Divine does not enter into typical linear patterns of time or into human cognitive frameworks. The Divine – like this special Moon being – surpasses all such limitations.

The Mond Crucfixtion (c1502) by Raphael. Note the Sun and the Moon. Courtesy The National Gallery, London

With its enticing shimmers and shadows, the Moon inspired many a medieval viewer, listener, writer and artist. As they looked to the Moon’s incandescence and its moments of darkness, medieval Christians and medieval Muslims were driven to see the Moon as a symbol in a range of religious teachings. This is not surprising. But what is surprising is the complexity and power of the Moon as a symbol, from simply playing an iconographic role to actually representing the Divine himself, in all his refulgent glory. What we see is the Moon taking on a range of roles and meanings, not unlike its shifting forms in the sky, as it moves through its waxing and waning phases. In its array of glittering forms, the Moon was a deeply meaningful and pressing symbol to both these religious traditions of the medieval world.