All of us can imagine the medieval world. Our imagination was created by our upbringing, the books we read, and the films we saw. Imagining the Middle Ages is an act that usually starts in childhood, and changes slowly as we grow older. From the brightly coloured pages of a child’s history book to the visceral panoramas of the latest season of Game of Thrones, how we see the Middle Ages changes. In most cases, however, the fundamental perspective remains the same: it’s an elite view of the medieval past, a Middle Ages composed of princes and kings, of knights and fair damsels in distress. It is a vision of the past that includes the splendour of great cathedrals and the brooding darkness of mighty castles. A past of banquets and battles. But it has little bearing upon reality.

The problem with our view of the Middle Ages is that it excludes the vast majority of people who lived in it, so it’s a highly partial and misleading picture of that world. Just like today, most medieval people did not belong to top 5 per cent of society, they weren’t kings, princes, knights, or damsels. Most men, women and children were commoners. It is no coincidence that this other, everyday, 95 per cent of the population was the one who did most of the work.

Putting aside farming, food processing and survival, it was these workers who were responsible for actually building most of what we think of when the Middle Ages come to mind. These are the people who built the magnificent medieval cathedrals, the craftsmen who constructed the dour and monumental castles. The workers whose blood and sweat bonds together the stones of every medieval church. They are the men whose deft fingers filled window spaces with blindingly bright stained glass. These are the people who built the Middle Ages. Yet we really know very little about them.

Composite image including a tiny selection of the many thousands of medieval compass drawn designs being discovered in English churches

The voices of medieval commoners are largely silent. The science of archaeology tells us something about their general health, about what they wore, where they lived, and what they ate. Modern techniques such as isotope analysis can even tell us details such as where they grew up. The wonders of modern science have their limitations, however. Archaeology and isotope analysis cannot tell us what these people felt and thought, what they dreamed of and feared, what they thought was funny or what they held dear.

Most medieval documents come with the same limitations. Occasionally, the lower classes turn up in the odd surviving document, account book or legal proceedings but, with low levels of literacy throughout much of the Middle Ages, these documents are usually the work of third parties. They were written and compiled by the priests, scribes and lawyers of the elite. They refer to the lower orders, but are most certainly not in their own words. Even where they turn up in the bright borders of illuminated manuscripts, it is alongside the fantasy beasts and grotesques of the medieval imagination rather than as a reflection of reality. Their voice – the voice of the medieval commoner, of the vast majority of medieval people – is largely lost.

The past five or six years have seen a massive rise in one particular area of medieval studies – an area that has the potential to give back a voice to the silent majority of the medieval population. Specialists have been studying medieval church graffiti for many decades. But new digital imaging technologies, and the recent establishment of numerous volunteer recording programmes, have transformed its scope and implications. The study of early graffiti has become commonplace. The first large-scale survey began in the English county of Norfolk a little over six years ago. Norfolk is home to more than 650 surviving medieval churches – more than in any other area in England. The results of that survey have been astonishing.

Enigmatic seventeenth century memorial inscriptions from Norwich cathedral

To date, the Norfolk survey has recorded more than 26,000 previously unknown medieval inscriptions. More recent surveys begun in other English counties are revealing similar levels of medieval graffiti. A survey of Norwich Cathedral recently found that the building contained more than 5,000 individual inscriptions. Some of them dated as far back as the 12th century. It has also become clear that the graffiti inscriptions are unlike just about any other kind of source in medieval studies. They are informal. Many of the inscriptions are images rather than text. This means that they could have been made by just about anyone in the Middle Ages, not just princes and priests. In fact, the evidence on the walls suggests that they were made by everyone: from the lord of the manor and parish priest, all the way down to the lowliest of commoners. These newly discovered inscriptions are giving back individual voices to generations of long-dead medieval churchgoers. The inscriptions number in the hundreds of thousands, and they are opening an entire new world of research.

Today, graffiti is seen as both destructive and anti-social. It is widely regarded as vandalism, not as something to be encouraged on ancient monuments and historic sites. That attitude is largely a modern one. Until recent centuries, people of just about every level of society carved graffiti into ancient buildings. It simply wasn’t seen as something to be condemned. The Coliseum in Rome, or Bodiam Castle in England, to take just two examples of key European heritage sites, are covered in centuries-worth of graffiti. Many of these inscriptions were created by members of the upper classes undertaking a ‘Grand Tour’ at the end of their education, and date to the 18th and 19th century. In the same tradition, early visitors to the Egyptian pyramids didn’t even need to carve the graffiti themselves – they could hire someone to do it for them. Graffiti was seen as something that was both accepted and acceptable.

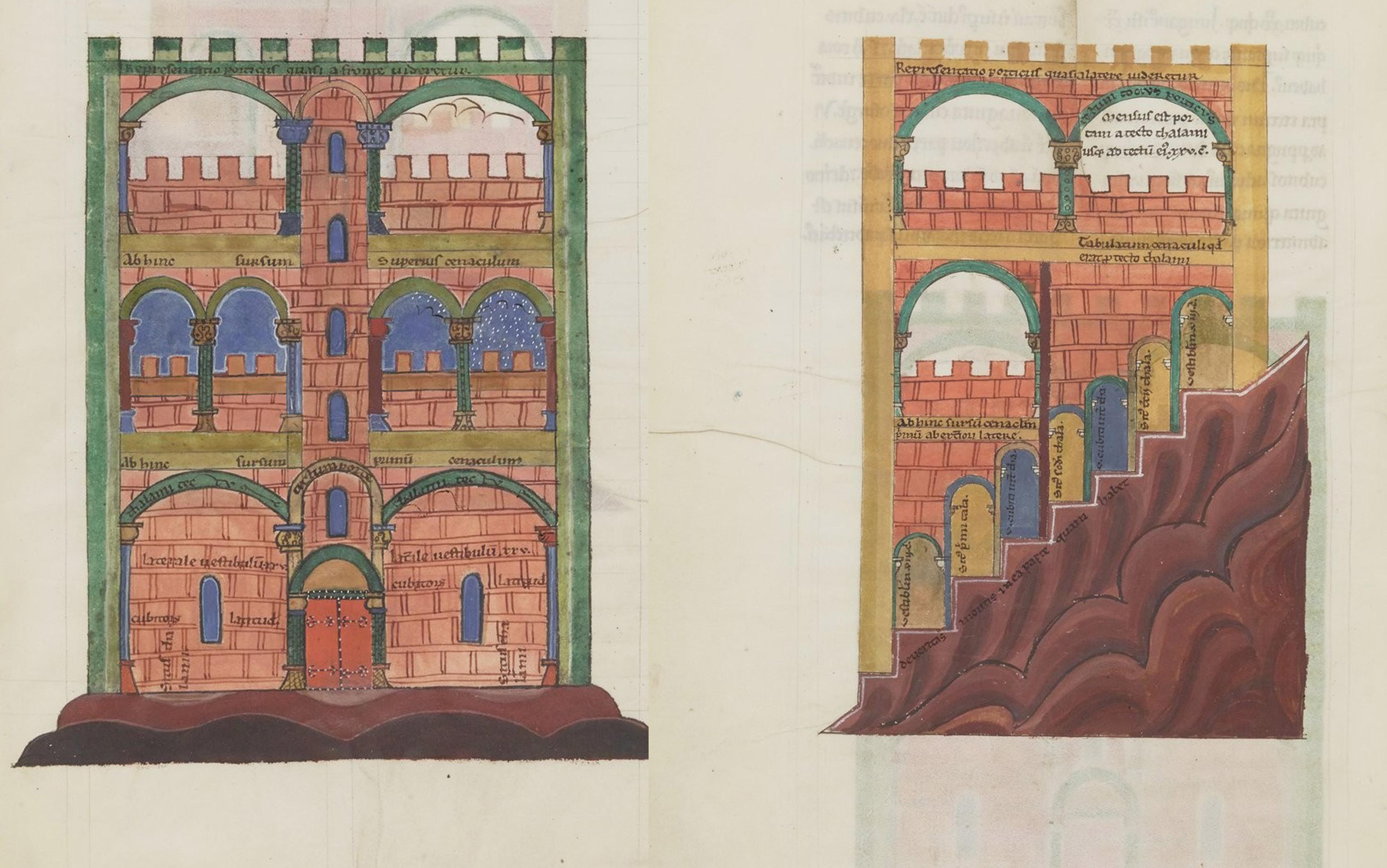

Medieval masons, the people who actually built these monuments, left the earliest markings to be found on any medieval church or cathedral. The traditional story is that each individual mason would have his own personal mark, which he’d inscribe wherever he’d worked. These angular marks, known today as ‘mason’s marks’, acted as a form of quality control. They also allowed the ‘master mason’, who doubled as architect and paymaster, to calculate how much each of his workmen was due to be paid. Masons today continue this old practice of marking their work, but their marks are more discreet, hidden away between stones and in darkened corners. Occasionally, the medieval masons left something more.

Their pragmatic approach to the construction of these stone monuments meant that the walls themselves sometimes served as drawing boards. In a few cases, such as at Binham Priory in Norfolk or Ely Cathedral in Cambridgeshire, intricate working drawings can be found etched into the stones. The designs at Binham all appear to relate to the building of the priory’s great west front in the 1240s. It is one of the earliest marvels of gothic window design to be built in England. The nameless master-mason who undertook the work was apparently unfamiliar and uncomfortable with this innovative style. Step by step, he worked out the specifics of the design on the walls of the half-finished priory church. Sadly, the great west window, which acted as a centrepiece to the design, structurally failed in the late 18th century. It then had to be bricked up – and remains so today. From the mason’s inscriptions, however, we have a clear indication of how this groundbreaking design would have looked.

Witch marks were, simply, prayers made solid in stone

Many of the markings discovered in medieval churches are all but identical. A survey of a church in northern England will reveal the same graffiti motifs and markings as those found in a church on the English South Coast. Even more remarkably, the same medieval markings recorded in most English churches are in churches across the whole of western Europe. Essentially, everywhere the medieval Christian church thrived, medieval Europeans inscribed their places of worship with the same graffiti marks. Known as ‘ritual protection marks’, medieval people believed that these symbols warded off evil influences. Today they are more commonly called ‘witch marks’.

Witch marks make up about a third of all recorded inscriptions. This means that we have many, many thousands of examples of them. Some churches, such as that at Cowlinge in Suffolk, can contain many dozens of witch marks. It is a rare church that doesn’t contain at least a small collection. These markings make clear the differences between the medieval and modern concepts of graffiti. Much modern graffiti tends to be collections of names and dates, examples of people ‘leaving their mark’ upon a place. However, witch marks belong to the world of faith and spirituality. They were not a replacement for the orthodox prayers of the Christian church. As much as the Church might have disapproved, people used them in association, as supplements to orthodox prayers. They enhanced the spiritual, and symbolised God’s protection from the powers of evil. They were, simply, prayers made solid in stone.

What makes the witch marks even more powerful is that they were also personal. The religion of medieval England was one of hierarchy, with parishioners’ own worship and interactions being organised and mediated by the parish priest. The priest, in turn, was subservient to the local bishop and, eventually, to the Pope himself. The prayers in the stonework altogether bypass that hierarchy, and it’s a hierarchy from which almost all other historical sources from the medieval world originate. These are personal interactions and statements by everyday members of the parish congregation with ‘their’ God. There is no need of intercession by priests, bishops or the Pope. In that way, they reveal things that the official, learned histories of medieval religion never can. These are not actions based deep in medieval theology and scholarly argument. They are acts of personal faith and belief, reflecting real people’s hopes, dreams and fears.

Many of the other images on the walls were born of an agricultural society. We see windmills, horses and geese – fixtures of peasant life. These are things that they saw every day, that were important to them, and essential to their ability to feed themselves and their families. The walls are also covered in the mundane: images of the people themselves, their faces and hands. In some cases, they left full-length portraits. Staring at the medieval walls long enough will sometimes result in the walls staring back.

Beasts and dragons are also included in the graffiti. They are strange and misshapen creatures, who seemingly walked, or flew, straight off the decorative borders of an illuminated manuscript. There are images of knights on horseback, heraldry and coats of arms, suggesting that the graffiti was either created by those from the knightly classes, or perhaps those who aspired to be. The walls are full of the peoples’ hopes. They also contain their darkest fears.

Take, for example, angels and demons: the medieval church was awash with images of them. Angels were carved into the elaborate roof timbers, their wings outstretched soaring high above the congregation. Angels flew in the bright wall paintings that once adorned almost every medieval church, passing news to the Virgin Mary or leading the souls of the departed heavenward. Angels guarded the ends of dark wooden pews and pale stone fonts, carved there, bearing shields emblazoned with the arms of saints.

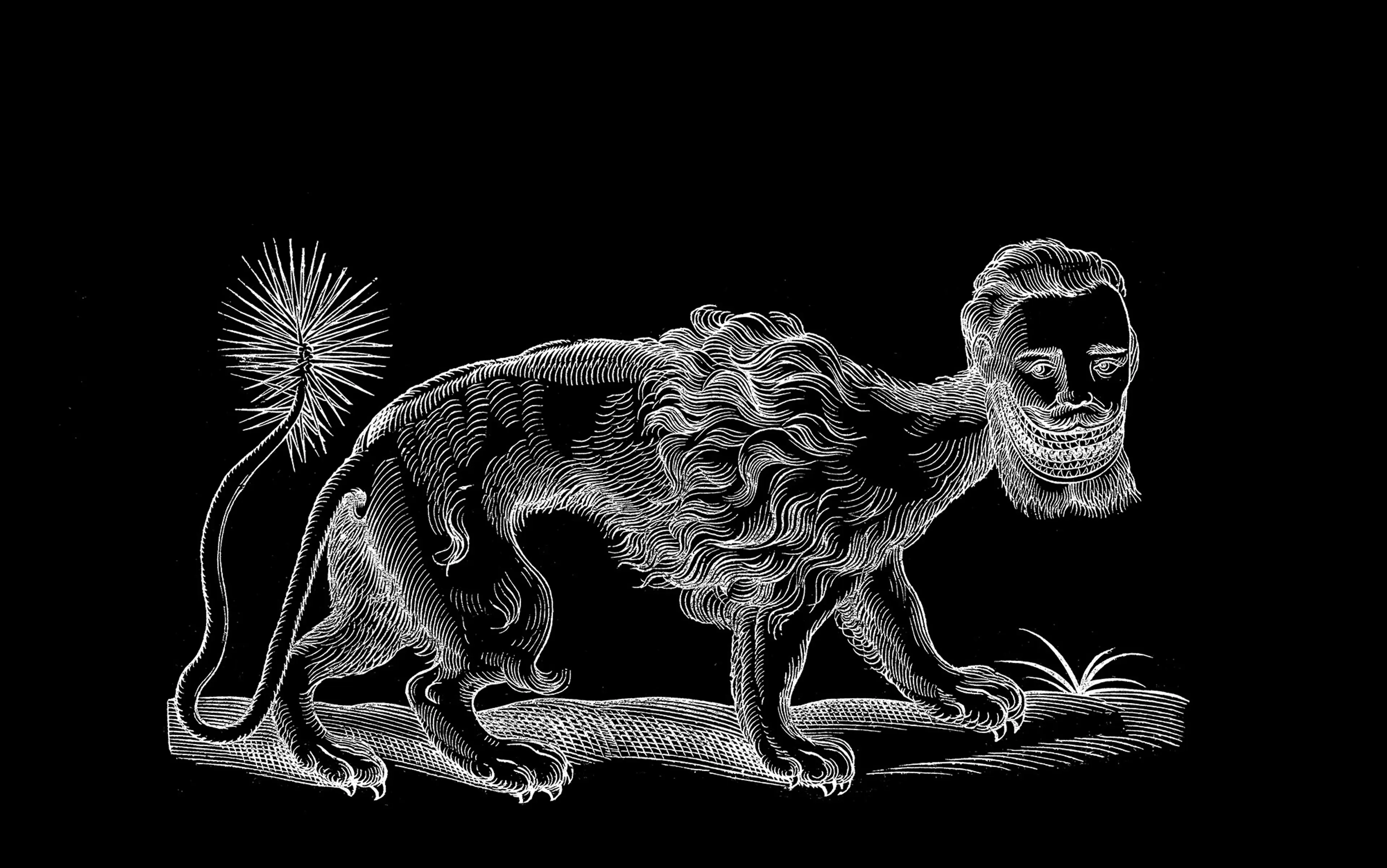

The demons are there, too. Grotesque beasts painted on the walls above the chancel arch, casting the souls of the damned down into the everlasting sufferings of hell. Comic demons sitting beneath the carved seats of the choir-stalls, bared backsides raised to noisily salute the clergy who perched upon them. Demons in coloured glass dance in the windows.

Demons were very real, and to be feared. This fear drove people to carve their counter-curses into the walls of the parish church

But while the medieval church was formally adorned with angels and demons, when it comes to the graffiti on the walls, there are only demons – many dozens of them, from the grotesque to the comic, dancing across the angel-free stonework.

Medieval demon complete with ‘flesh hook’ still stalking the walls of Beachamwell church in Norfolk

Why are there no angels? The reason is quite simple. The graffiti on the walls shows only what those who made it thought was real and immediate. Angels were heavenly beings. They littered the pages of the Bible, but could not be expected to play a part in the lives of the people in the world. Demons, on the other hand, were very real indeed. It was demons who were responsible for any sudden illness or unexplained death. Demons brought down a blight upon the harvest crops. Demons unbalanced the mind of the simpleton, and brought on the terrifying storms that could lay waste a whole year’s crop in a single afternoon. Demons were real and to be feared. This fear drove medieval people to carve their counter-curses into the walls of the parish church.

Of all the graffiti being recorded in English churches, text inscriptions are actually rather rare. They make up only about 5 per cent of all the discovered markings: again, a distinct difference with modern graffiti. The rarity is in part a result of the low rates of contemporary literacy, but it is also testimony to the power of images over the written word. Many of the text inscriptions are difficult to read even by long-practiced historians. Generation after generation of wear and abrasion has left them in a sorry state. Even those that can still be made out are sometimes less than illuminating. The poor level of education among some parish priests, and the use of shortcuts and contractions, is reflected in the sometimes appalling attempts at Latin found on the walls. In many cases, the Latin is so bad that the only person who could probably have read it was the very same person who wrote it. Sometimes the writing on the walls simply can’t be read.

So what are these ancient markings on our medieval churches? Are they simply the random scribblings and doodles of bored choirboys, or do they have a deeper significance? Is there a meaning to some of them beyond the obvious? Beyond the simple statement of ‘I was here’? Recent research suggests that, yes, they are very important.

One of the most striking types of medieval graffiti is that of medieval ships. These small images are among the best-studied of all the graffiti, and are beginning to shed light on the mystery of exactly why they were made. When the modern surveys began, it was widely presumed that ship graffiti was confined to coastal churches: simple images created by local people of the ships they saw every day. However, research has shown that ship graffiti is found just about anywhere in the country. There are examples from Wiltshire and Leicestershire, about as far from the sea as one can get in mainland England. Even more intriguing, all the examples of ship graffiti, even those found many miles inland, appear to show sea-going vessels. The church at Blakeney, on the north Norfolk coast in the east of England, can help to explain why there is so much graffiti of these little ships.

Simple late medieval example of ship graffiti from Cley-next-the-Sea church in Norfolk

Blakeney’s church is covered in early graffiti inscriptions, and they are spread fairly evenly throughout the building. All the dozens of examples of ship graffiti, however, are to be found clustered in one clear and distinct area. Without exception, all of the images were inscribed on the pillars of the south arcade – and most are on the single pillar that sits at the eastern end. According to maritime historians, the images were created over a period of 200-300 years. Despite this, each little ship respects the space of those around them, never crossing over one another. This tells us that the earlier ships were still clearly visible when the later images were created centuries later.

People sat in the dark, praying for the safety of a long-drowned ship, and etched their fears and demons into the walls

It is, however, their location that holds the real clue to their meaning. The eastern pillar into which they are carved sits opposite the side altar in the south aisle. From the historical record we know that this altar was dedicated to a church’s patron saint. In the case of Blakeney, that was Saint Nicholas. Now better known for his association with children and Christmas, throughout the Middle Ages St Nicholas was regarded as the patron of ‘those in peril upon the sea’. The ship graffiti is clustered around the St Nicholas altar for a reason. Historians and archaeologists believe that each of these little ships was a ‘votive’ offering – quite literally, a prayer carved into the stonework. Exactly what that prayer was, we might never know. Was it a prayer of thanksgiving for a voyage safely undertaken, or a prayer for safe passage on a voyage yet to be made? The fact that some of the ships appear damaged has led some to suggest that these might be prayers for ships, crews and loved ones that never made it home.

This is the true value of searching out these ancient inscriptions on the wall. These little prayers and etchings offer one of the few avenues into the hopes and feelings of those who left their mark many centuries ago. It is not a world of knights, princes and kings. It is a world of real, fallible human beings. People who sat in the dark, praying for the safety of a long-drowned ship, and etched their fears and demons into the walls. Quite simply, the medieval graffiti gives us back the lost voices of the medieval world.