I was lying in the dust, staring into the African sun, when their swords came down on me. The crowd was about a hundred strong, all of them Muslims shouting in a sonic blur. First they began slicing my arms. Next, pulling my shirt open, they cut into my torso. My eyes were closed with pain by the time I felt a blade moving hard across my throat. I thought I would die there, in that poor Durban neighbourhood where, despite the warnings of middle-class South Africans, I had decided to go exploring that evening.

Just minutes earlier, I’d turned a corner into a crowd of African and Indian Muslims. And then I was on the ground, being sawed with swords. When they finished with my throat, a dozen hands pulled me up again. Soaked in blood, I opened my eyes and saw it was just sweat. I was not even bleeding, though the scarlet lines from the sword strokes left wheals in my skin for months. Everyone was shouting, ecstatic. It was a miracle, a show of faith and power in which the Africans with the swords were well-practised. They were Rifa’is, a brotherhood of lower-class Sufis, and in the eyes of the assembly I had inadvertently renewed their prestige.

There are few of these Rifa’is left now, but a century ago they were numerous enough for travellers to give them a special name. They were called the ‘howling dervishes’, as a coarser counterpart to the elegantly balletic ‘whirling dervishes’. That latter name survived as a figure of speech when the ‘howling dervishes’ were forgotten. But this demeaning name hides a history of entanglements between Europeans and Muslims that redefined the Islam we now call ‘Sufism’. Together, European scholars and Muslim reformists decided that the popular and festive traditions of such dervishes were not true Islam, and not even true Sufism.

Writing in History of Persia (1815), the East India Company diplomat John Malcolm remarked that the Islam of the Sufis ‘is the dream of the most ignorant and the most learned’. Two centuries later, Malcolm’s epigram makes a good place to start thinking about the mystical Islam known as Sufism. On one level, it encompasses much of the popular practice of Muslim religiosity: it is an Islam of saints, miracles, pilgrimages, and popular displays of charisma of the kind I encountered in Durban. On another level, it consists of mind-bogglingly complex treatises in philosophical Arabic. This philosophical Sufism dwells on such doctrines as the ‘passing away’ of the lower self, the meaning of the Qur’an’s mysterious secret letters, and the ‘light of Muhammad’ manifested at the dawn of creation from God’s own primordial light.

At the same time, Sufism consists of an unfathomably rich tradition of poetry written in Arabic, Persian, Urdu and many other languages. The West knows little about this literature. This ignorance is a loss, for Muslims and non-Muslims alike, because such poetry – and its jokes and iconoclasm – forms a historic literary testament to a shared humanity.

Sufi poetry abounds in humour, learning and bawdiness. The Persian narrative poems of Rumi, the 13th-century Sufi, contain so many sexual innuendos and downright brazen images that Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, the Cambridge don who translated them in the early 20th century, blushingly rendered those parts into Latin. Materterae si testiculi essent, ea avunculus esset is, in Rumi’s rawer vernacular: ‘If an aunt had any balls, she’d be an uncle.’ Another of Rumi’s more notorious tales involves sex with a well-endowed donkey. Such sections have been omitted from Rumi’s poetry anthologies that the enthusiasms of Madonna pushed into the US bestseller lists a few years ago.

Dirty jokes don’t fit with current impressions, learned or popular, of Islam. It’s a dangerous excision. Omitting the rich history of this avant-garde encourages the misapprehension that present-day conservatives have some superior claim to cultural and religious authenticity over today’s Muslim liberals.

More popular, in past and present, than these bawdy tales was the lyrical tradition of Sufi poetry, in which the poet as vagabond speaks the raucous language of the demi-monde, adopting the guise of the homeless wino. In the words of the medieval poet Jamali Dihlavi, the Muslim is the seeker wandering the earth in search of the beloved of whom he once caught the briefest glimpse:

Listen, my boy, to the tales of a tavern-haunter,

So you can roam down the same road yourself.

Whoever becomes a bandit on God’s highway

Will turn to tavern once he’s seen the light.

Dihlavi cut a similar figure to the more familiar Arthur Rimbaud, the 19th-century French poet who, like Dihlavi, plumbs the depths of self-negation before finding simpler, physical ways to lose himself. Like many of the Sufis, Rimbaud immortalised in verse his tortured humanity before walking off into the sunset and disappearing into Africa.

He mirrors the Sufi poets in another way too: spellbound readers make private pilgrimages to Rimbaud’s grave, at his home in Charleville, in provincial Ardennes. Yet, in scale, their visits can’t compare with the adulation shown in the mass pilgrimages to the graves of the Sufi poets of South Asia.

That is why fundamentalists have destroyed so many Sufi shrines and places of pilgrimage: the poetry sung at those places celebrates and advances an Islam that rejects political power

Every year, thousands of festivals around the tombs of Sufi saints in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh demonstrate the vitality of Sufi poetry. Dotted throughout town and countryside, the shrines where these saints are buried still form the focus for the spiritual lives of tens of millions of Muslims. Their doors and rituals are open to people of any religious background; as a result, Sufi shrines in India still play an important role in the religious life of many Hindus and Sikhs. The work of the great Baba Farid, a 13th-century Punjab Sufi poet, also exemplifies this long history of religious co-existence, as his poems form the oldest parts of the Sikh scriptures.

Farid’s poems are still recited in Sikh temples around the world. In one of the verses from the Adi Granth (the sacred scripture or ‘First Book’ of Sikhism), Farid declares in rustic and homely Punjabi:

Ap li-ay lar la-ay dar darves say.

Translation: Those tied to Truth’s robe are true tramps on the doorstep.

The seeker after Truth must become a wandering beggar. The word Farid uses is darves, or ‘dervish’ – literally, a vagrant who goes from door to door. Read again that alliterative line of Punjabi: Ap li-ay lar la-ay dar darves say. It has the simple rhythm of repetition, the call of love’s beggar traipsing from house to house.

What the German philosopher Max Weber described as the disenchantment of the world, modernity’s discrediting of the supernatural and magical, has not been good for these beggars, these mystical troubadours, especially among the Muslim middle classes. Their pilgrimage places, however, retain mass appeal, especially among the large populations of poor and uneducated people. That is why fundamentalists, whether the Pakistani Taliban, the Saudi government or ISIS, have destroyed so many Sufi shrines and places of pilgrimage. The poetry sung at those places celebrates and advances an Islam that rejects political power, an Islam incompatible with the ambitions of religious fundamentalism. It is an Islam antithetical to political Islam, which sees political power as the foundation of religion. Although not all forms of Sufi Islam are non-political, the Sufism of the dervishes renounced political power as the most significant impediment on the long road to their divine beloved. It is a spirit of Islam still very much alive.

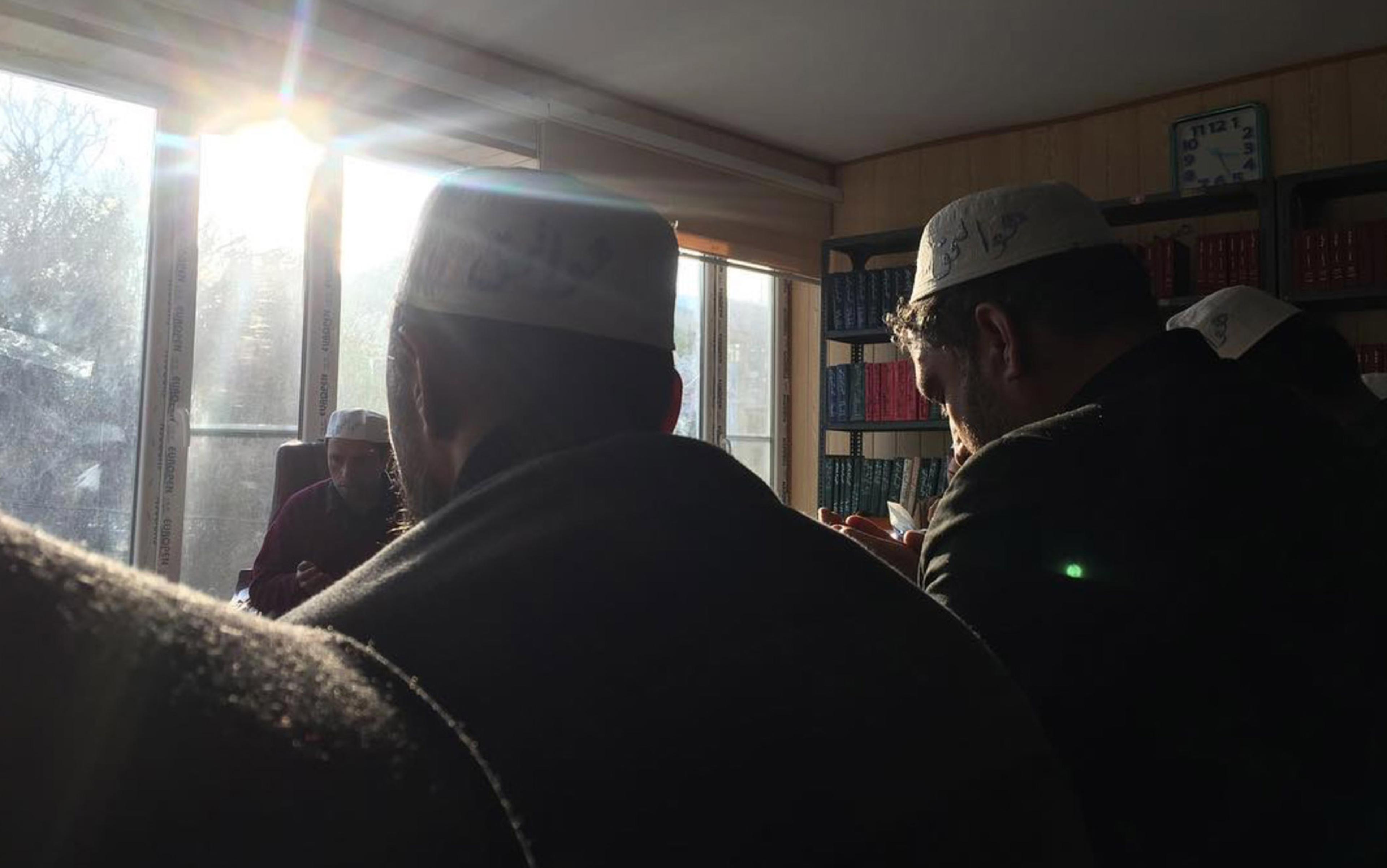

I have attended shrine festivals from Morocco to Pakistan where hundreds gather to hear Sufi poetry sung until the audience is brought to tears. These concerts are called layla in Arabic and mahfil-i sama in Persian. They are a continuation of the old Sufi custom of reaching ecstatic communion with God through music. One story recounts how a medieval Indian Sufi heard the following lyrics sung at such a concert in Delhi:

Har qawm-ra ast rahi dini va qiblagahi

Man qibla rast kardam bar samt-i kaj kulahiEvery people has a road, a religion and place of worship,

But me, I say my prayers to the beauty with the tilted cap.

It is an evocative image, the kaj kulah, or ‘tilted cap’: one can almost picture a Chanel advert. When the Sufi in old Delhi heard those lines, he fell into a state of rapture for his beloved, then keeled over and died of heartbreak. At Sufi concerts in India and Pakistan I have seen many scenes of such ecstasy, in which listeners leap up to dance wildly in tears.

In a Persian poem beloved by qawwali singers to this day, the 14th-century poet Amir Khusrow placed love above religious dogma:

Kafir-i ‘ishqam musalmani ma-ra dar kar nist

Har rag-i man tar gashta hajat-i zunnar nist;

Az sar-i balin-i man bar khiz ay nadan tabib

Dardmand-i ‘ishq-ra daru bajuz didar nist.I am love’s infidel; the Muslims’ creed is no use to me.

My veins are taut like wire; I’ve no need of the Hindus’ holy belt.

So go away from my sick bed you foolish physician:

For the lovesick, the only cure is a glimpse of the beloved.

The enduring popularity of Khusraw’s poetry is just one example of the continuity of classical traditions of Sufi Islam in today’s festivals and performances. The Prophet Muhammad captured the same blend of the sensual and the mystical when he said: ‘Made beloved to me from your world are women and perfume; and the coolness of my eyes is in prayer.’

For a long time, European scholars found it difficult to see this continuity of Sufi influence. Arthur Arberry, an influential mid-20th-century professor of Arabic at the University of Cambridge, saw degeneration instead. ‘It was inevitable, as soon as legends of miracles became attached to the names of the great mystics,’ wrote Arberry in Sufism (1950), ‘that the credulous masses should applaud imposture more than true devotion.’ Recognising the continuity of the grand poetry and philosophy of the Sufis of old might have undermined the authority of European colonisation. Instead, Arberry emphasised the decadence into which Islam in general and Sufi Islam in particular had fallen. ‘The cult of the saints,’ he continued, ‘promoted ignorance and superstition, and confounded charlatanry with lofty speculation.’

Imperial ‘orientalists’ such as Arberry erred in drawing this line between great, dead Muslims and living, decadent ones, between a fragile, fallen Islamic high culture and a benighted world of a Muslim Lumpenproletariat. The orientalists’ influence was so strong that they shaped the way Muslims came to see their own history. Educated Muslims were taught to look down on the ‘decadent’ Islam of the lower classes. But in the poor urban districts across the Muslim world, Sufi poetry is still read today. As they are less likely to speak English, and foreign journalists are unlikely to interview them, Westerners do not often hear from the multitudes for whom Islam is Sufi poetry.

Islam without Sufism is like French philosophy without existentialism, or French poetry without Rimbaud

The Age of Empire, Western Europe’s colonial domination of much of the Muslim world, played a formative role in both Muslim and non-Muslim attitudes to Sufi Islam. Like Oxbridge Orientalists, political Islamists look down on the religious practices of ordinary Muslims living in Asia and Africa as decadent and corrupt. Empire also lay behind the terms in which we have come to address mystical Islam. The more common words by which Sufis were known in their own languages were faqir and darvish. Both signify a beggar.

European travellers’ accounts of India and Iran during the Age of Empire described the fakirs and dervishes as dirty hobos and opium addicts, street people. By the late 19th century, Muslim reformers took this colonial criticism to heart. They blamed the fakirs and dervishes – in other words, the Sufis – not only for Islam’s supposed religious decadence, but also for the Muslim world’s loss of economic and political power. The poor repute into which orientalists and Muslim reformers threw the Sufis contributed to their marginality in Western representations of Islam. This marginality makes it much easier for fundamentalists to portray themselves as the spokespeople of the authentic Islam. However, Islam without Sufism is like French philosophy without existentialism, or French poetry without Rimbaud.

More pragmatically, dervishes were potentially dangerous anti-colonial leaders. In the Mahdist War (1881-99), Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, a Sudanese Sufi leader, led his army of dervishes against the troops of General Gordon in Sudan. In the years that followed, ‘dervish’ in the West became a symbol of fanaticism as well as decadence.

Recently in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, I found The March to Khartoum and the Fall of Omdurman, 1898 (price: three pence), a short pamphlet of poems by Private Henry Surtees dedicated ‘To General Gordon and the Men who fell during the Soudan Campaign’. Private Surtees’s poems make clear the political potential of spiritual language:

We forgot the trying marches

That we went on each day.

We longed to make the Dervish

For his past wrongs well pay.

Or:

The lad plucked up his courage,

And had another try;

And ’ere another minute,

He saw that dervish die.

Printed in bold at the end of Private Surtees’s booklet are the mortality statistics, sobering indications of the brutality of empire:

Total of killed and wounded: Anglo-Egyptian side – 50 killed, 342 wounded.

Dervish Side – About 11,000 killed, about 16,000 wounded.

One of the stranger outcomes of the defeat of the Mahdi was all the dervish paraphernalia that British soldiers carted back from Sudan as trophies of war. In the last pages of his unpublished memoirs, General Sir Archibald Hunter made two long lists of the dervish trophies he had collected. Today, those spoils of war provide a unique material archive of African Sufi culture. You will be hard-pressed to find such artefacts in the museum collections of ‘Islamic Art’ from Paris to Doha, funded as the museums are by Saudis and other Gulf states: the Saudis don’t consider such objects to represent ‘true Islam’. Scattered in regimental barracks and stately homes around Britain to this day, the brightly dyed cloaks and battle banners carried back from Sudan lend an extraordinary glimpse into both the artistry and influence of the anti-colonial dervishes. One such patchwork smock hangs on display in the tourist tea rooms in the Cotswold town of Cheltenham Spa. It is an apt place for an old brigadier’s trophies if ever there was one, but a sadly marginalised place for a dervish mantle.

With their colourful patchwork clothes, the less warlike and more typical dervishes – ‘those whose hearts have been broken’, as they often called themselves – made for a pretty sight. Travelling across northern India in the early 19th century, the missionary Bishop Reginald Heber came across two such figures. ‘Two dervishes, strange antic figures, in many-coloured patched garments, with large wallets… the elder, a venerable old man…raised his hand with much dignity and prayed for me.’ Very occasionally, on travels through Iran, Pakistan and Chinese Central Asia, I have encountered Sufi mendicants still wearing this traditional costume.

A hundred years ago, there were many of them to be seen. At the turn of the 20th century, one of England’s great explorers, the indomitable Ella Sykes, saw them regularly while she was living in Kashgar in what is now western China. Sykes described how people would wait for the dervishes to arrive singing new songs, picked up on their travels. She also left one of the most enjoyable descriptions of the dervishes of Iran: ‘They are striking-looking figures,’ she wrote, ‘in white garments of dubious cleanliness, with leopard skins flung over their shoulders on which flow their long unkempt locks from under a conical felt cap, often embroidered with texts. Sometimes they carry a begging-bowl, beautifully carved, and they go from place to place telling fortunes, giving charms and love potions.’ Such dervishes deserve their well-earned place in the history of Islam.

But as valuable as such artefacts and travellers’ accounts are, the most vital way to encounter Sufism remains its poetry. The greatest Sufi poet is the Indian Mirza Ghalib, arguably also the greatest Urdu poet. In his poetry, the deepest humanist and spiritual impulses of Islam find some of their most memorable expression.

Writing of paradise, for example, Ghalib mocks it, doubts it and hopes for it. Thus:

Mocking,

Why would I prize getting to Paradise,

If it weren’t for its red wine with the scent of musk?

Doubting,

I know the truth, but be that as it may,

The dream of heaven keeps me from dismay.

And hoping,

It’s all very well what they say about heaven –

All I care is that God allows you in to brighten it.

Although he tried to rise above it in his poetry, Ghalib could not escape the world of politics and empire. In 1842, his diminished pension was no longer enough to support him. Despite his fame, he sought a teaching position at Delhi College, which had been established by the British administration in India. He received notice of an interview. When he arrived at the college, Ghalib waited outside for his interviewer to come out to greet him, as any late Mughal gentleman would. But no one came out. Etiquette meant that Ghalib himself would have greeted even the humblest beggar to have called at his door, so he felt sorely aggrieved at the insult. His would-be interviewer, Sir James Thomason, later apologised for the cultural misunderstanding, explaining that, since it had been an official and not a personal meeting, British etiquette dictated that Ghalib come to Thomason, like any interviewee.

During Ghalib’s later years, following the 1857 Indian uprising against the East India Company, British and Sikh troops ravaged the old capital of the Mughal emperors. As Ghalib recounted in his Urdu letters, the daily conditions in which he lived became almost unbearably difficult. He had not, however, lost the sense of humour for which he was known. Citing a friend’s comments about him in one poem, Ghalib wrote self-mockingly:

All this Sufi business, Ghalib! And the expositions you give of its theories!

We’d have considered you a saint – if you weren’t such a drunkard.

Like many a dervish before him, Ghalib died penniless in 1869. As with the poems still sung at the tombs of Sufi saints from Pakistan to Egypt, his verse engages a life of common dilemmas familiar to anyone living in the world. Such poetry exemplifies the humorous and eloquent spirit of Islam which finds devoted followers from Manila to Marrakech. The boisterous Rifa’is who made a miracle of me in Durban are few now. But the poetry of the Sufis is still being recited.