A cursory online search will provide you with nearly 100 million web pages concerning ‘the Left’s circular firing squad’. The idea of a circular firing squad is meant to evoke people so torn by their minor differences that they eliminate any possibility for solidarity or collective work. Rather than aiming our weapons at our enemies, we somehow get mixed up and begin to aim them at our friends. The supposed results of all this fighting: cancel culture, illiberalism, tribalism, hyper-partisanism. In other words: we become intolerant and start seeking to exclude anyone who presents us with any different ideas at all.

This exclusion of difference arises, according to the political philosopher Robert Talisse, due to too much democracy. He argues that political polarisation is a ‘loop’ such that, once we are in the ‘trap’ of politics taking over our lives, we struggle to escape from them because it leads us to polarised beliefs – like the 40 per cent of Americans who at one time believed that Joe Biden was not the legitimately elected US president. The result, as Talisse puts it, is that ‘[w]e become enamoured with the profoundly antidemocratic view that democracy is possible only among people who are just like ourselves’. After all, democratic choice gave us Brexit. It’s well known that democratic decisions can be catastrophic for minority populations and can enact brutal policies toward their elimination. At base, it is claimed that the fault of our dysfunctional politics is a democratic urge to overly agitate conflict, combined with a tendency toward in-group bias, or a preference for people like ourselves. Implemented where it shouldn’t be, democracy causes the very thing it is supposedly meant to solve: too much disagreement.

Talisse is not alone in identifying conflict as a problem for politics. Most forms of political organisation find ways to manage and mitigate conflict among the members of the polity. In this is the recognition that disagreement is a feature of human social life that is more or less permanent. This means that democracy must also find a way of handling our conflictual tendencies. So, what types of conflict does democracy require and how can conflict threaten democratic practices?

To accommodate conflict in a theory of democracy, we first have to stop thinking of conflict as simply one thing. The idea of conflict may raise the spectre of violence, shouting matches and general name-calling. These things certainly can form parts of conflicts. However, that doesn’t tell us anything about the character of the conflict itself – what is the conflict for and why do we do it?

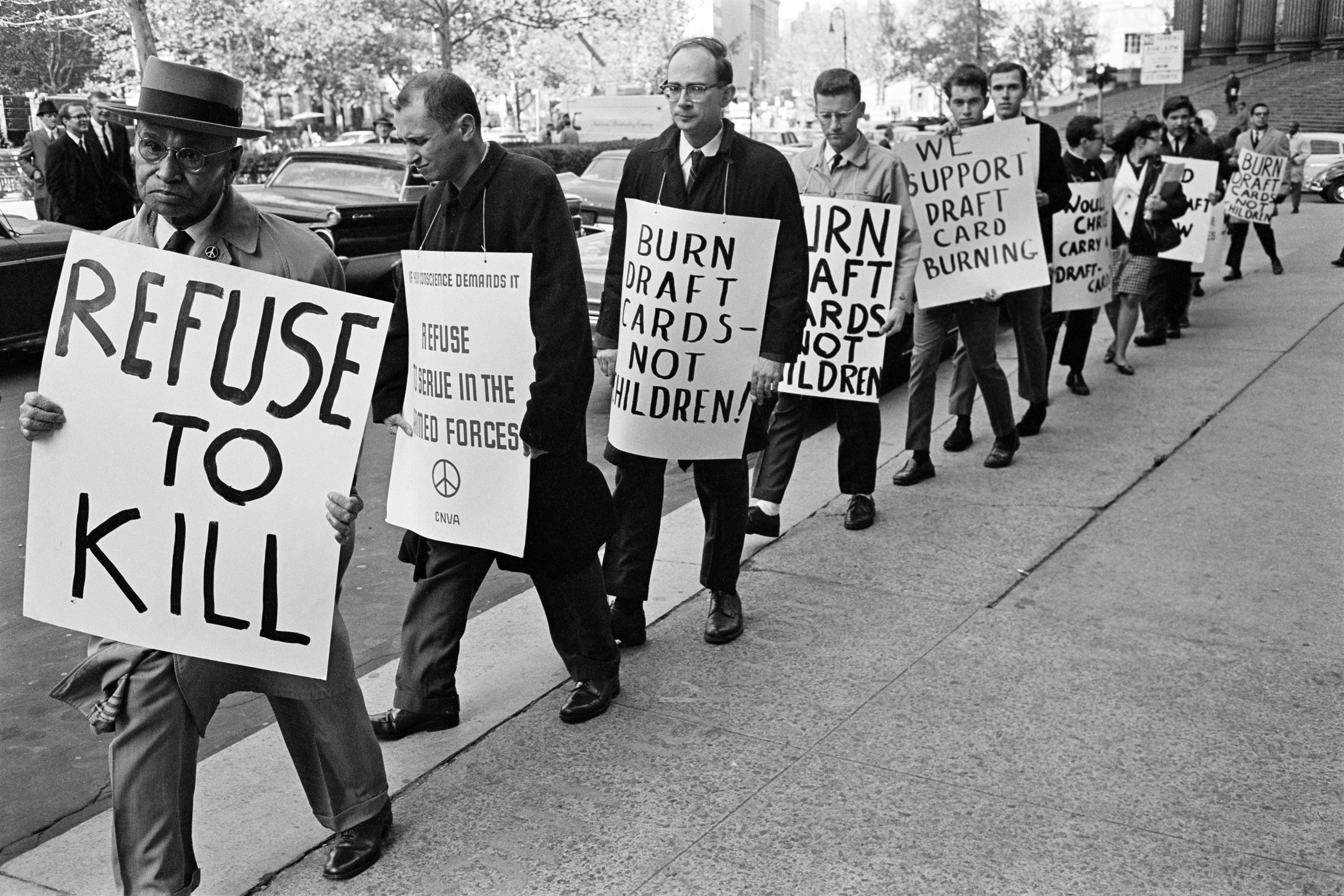

According to Lewis Coser’s Continuities in the Study of Social Conflict (1967), conflict comes in two sorts: realistic and non-realistic. Realistic conflicts are when something undeniably real is at stake. This is when there is a substantial element to the conflict, such as a disagreement over something in which two individuals or groups cannot both have their way. When a union and management conflict over the content of a contract, there is something very real at stake. On the one hand, there are the working conditions, the living conditions, the concrete life-possibilities of the worker; on the other, there are the profits of shareholders, the prices of goods and services, and the pay of managers and executives all on the line. Real conflicts are not limited to wages but they arise from any way that someone’s demands can be frustrated. A real conflict occurs because one demands what the other refuses to give, be it wages, voting rights, healthcare, respect or recognition.

Non-realistic conflict, on the contrary, has a psychosocial function. It’s being quarrelsome for the pleasure of annoying or, as it may be, annihilating, your enemy. Many popular types of trolling are versions of non-realistic conflict. There’s no specific disputed content to it. Rather, the content is just reflective of a desire for psychological satisfaction. When people mob others, call each other names or generally participate in what some political commentators contemporarily call ‘tribalism’, this is the type of conflict they are deriding. It’s thought to exist purely for the satisfaction of determining an in-group and out-group, and places those who deploy it in a hierarchical relation to those who are targeted. Yet no demands are made, and so no one’s aims can be frustrated.

In conflict, we wear away at each other, making each other more perfect in the process

When we think more carefully about how conflict operates in our society, we can see that it isn’t always something we should avoid, even if we could. It’s reasonable to believe that non-realistic conflict is at the heart of much of the unpleasantness of our social lives. You may even think that these sorts of conflicts, driven as they often are by forms of identitarian prejudice, ought to be fully eliminated. It would be good, all things considered, for a society to have no more racist name-calling, an end to degrading treatment of women, and no desire for members to dominate each other by virtue of morally arbitrary characteristics like religious belief. But, often, a push to eliminate the sort of conflict that is bound up with historical systems of domination can also affect another sort of domination by excluding some participants, concerns or means of conflict from democratic life.

Conflict’s role in democratic social life, though it seems heightened now, is not new. Enlightenment-era thinkers posited that human beings have an ‘unsocial sociability’ – a social tendency toward conflict. As Immanuel Kant theorised it in ‘Idea for a Universal History with Cosmopolitan Intent’ (1784), this tendency is part of the natural aim of perfection in human beings. In conflict, we wear away at each other, making each other more perfect in the process. Left alone to our own devices, truly unsocial, we fail to fully develop because we do not hit up against each other in conflict. Of course, we cannot have this form of unsociability without also engaging in sociability itself. To come into conflict is to participate in sociability. For instance, when we don’t wish to engage in social bonds with others, we often just refuse to participate in conflict with them. We may believe them wrong or misguided but, unless we see ourselves as participating in some kind of collective project, we may as well leave them alone. Addressing our differences is a way of showing that we matter to each other in some way.

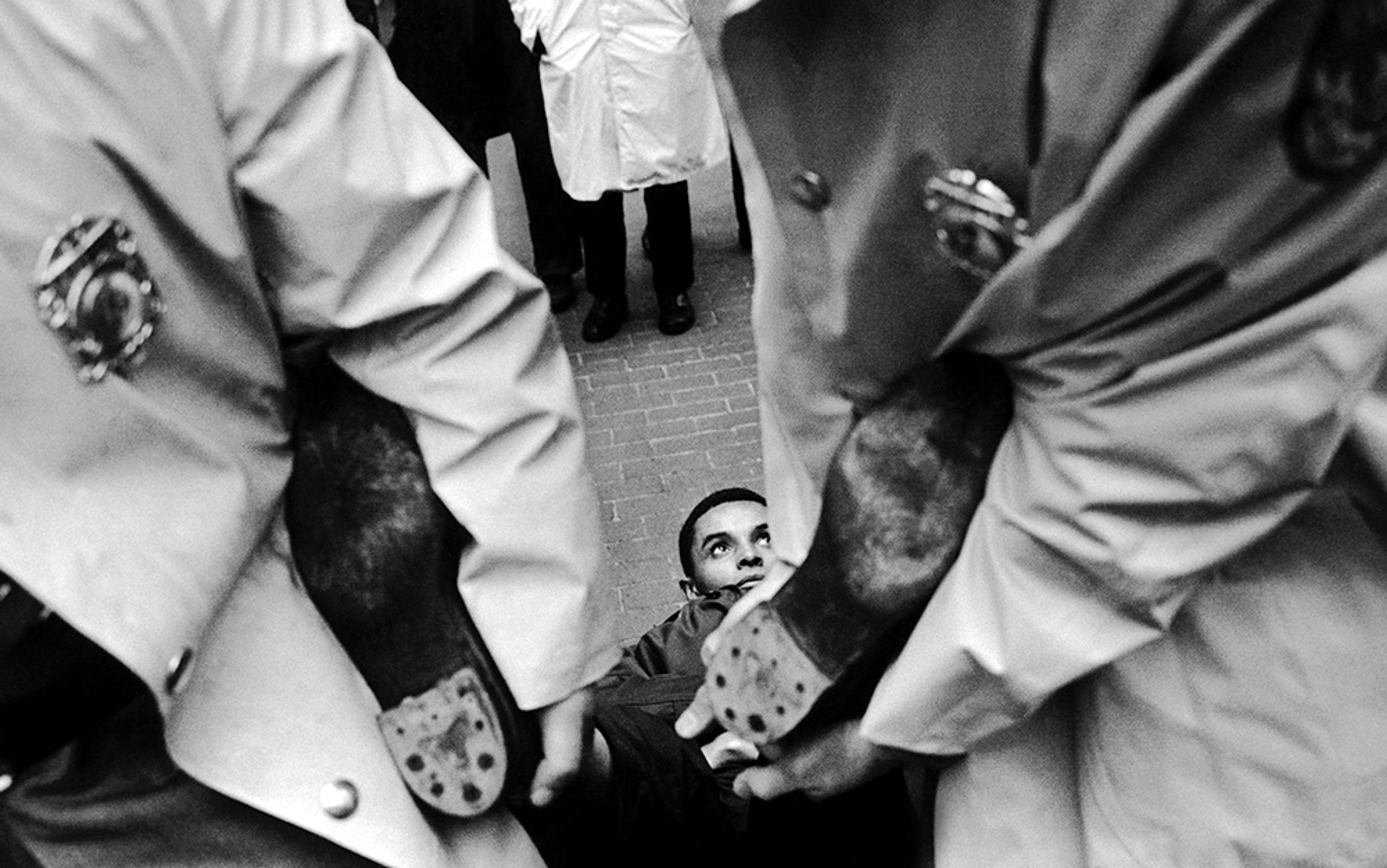

However, there are other ways of addressing differences that flow through conflict that do not involve the type of disagreement alluded to above. Historically, this includes the expulsion, exclusion or extermination of people who either hold politically marginalised views or are members of marginalised classes. When we think of conflict, we should think of its importance but also its dangers, via the thought of Carl Schmitt. An unrepentant Nazi jurist, Schmitt developed a political theory based on a political structure called the ‘friend-enemy’ relation. According to him, writing in 1932, the friend-enemy relation is conceived as fundamental to politics, which is itself the form in which human beings live out conflict. On this account, to be political is to be in conflict. Agonism, the notion that conflict can be helpful to politics, is drawn from Schmitt’s writing.

The agonistic view of the world, though, also relies on the notion that we live in an irreducibly pluralist world – we simply will continue to disagree with each other concerning things that are of central importance. Yet this risks making it appear as though we should agitate as much conflict as possible. If conflict is both inevitable and beneficial, then even more conflict must be even more beneficial. Often, it is this view of conflict that is depicted as incompatible with democratic politics and ways of life, for instance by Talisse above. Whatever else democracy requires, it is fundamentally, at least a little bit, about coming to agreement. Democracy seems to be about organising ourselves when we disagree fundamentally about values, tactics, policies and what a good life may be. This means that, while conflict is fundamentally an impetus for democratic processes, these processes are also about ending it. But, alongside these agreements, we must be willing to hold disagreements, consider dissensus, and allow for conflict.

So, conflict isn’t going anywhere – because, when our disagreements are substantive and concern real demands, over which there is broad disagreement, we cannot simply eliminate conflict. We can try to exclude it from our thinking about democratic value or our idealised theory but, to the extent that we do, our theories are a fundamental misfit with the reality of everyday political life. Because we cannot hope to do away with conflict, we have only a few options. One is to theorise conflict out of existence. Another is to minimise conflict by dismissing those who agitate it (to the extent that we are able to do so). The last is to build both a theory and a politics capable of handling this seemingly ever-present feature of our social world.

Traditional means of eliminating conflict are either liberal or authoritarian. Often, the liberal response to conflict is a form of exclusion. If you disagree, your position must not be rational. This allows liberals to dismiss many forms of conflict as non-realistic. In part, this exclusion relies on the presumption of what types of conflict can be agitated and how complaints must be leveraged.

Authoritarian means of eliminating conflict are what we would more generally consider classic forms of state repression: banning books, freedom of conscience, freedom of the press, freedom of thought or belief. But authoritarian means of eliminating conflict don’t stop at attempting to control people’s behaviours (something that all governments do via laws, to some extent). Authoritarian means of eliminating conflict include not just forms of suppression but also extermination, expelling and annihilating those who are viewed as the source of conflict.

In both liberalism and authoritarianism, conflict is diminished in order to streamline a process of legitimation – making room for agreement that can serve as justification for the use of state power. One can imagine a situation in which all those unwilling to go along with a political order are jailed, deported or killed. What remains would be an order capable of democratic legitimation, by most people’s understanding of it – this is the specifically antidemocratic threat that Talisse identifies. However, the process for achieving that order would betray the horror and injustice of the intentional exclusion, expulsion and annihilation of dissent. It isn’t so much that democracy requires creating conflict, but that it requires actually dealing with the already existing conflict in our world. We cannot simply pretend that we all agree, or that if we were rational (and not quarrelsome) then we would.

If the organisation specifically excludes trans women, then it is imposing a certain kind of domination

Whatever means we have for avoiding, minimising or eliminating conflict cannot put the cart before the horse by determining which conflicts arising from whom are legitimate for a democratic society to discard. Which conflicts are considered to be necessary and which are superfluous themselves requires a democratic hearing. In the same way as it is clear that members of a polity shouldn’t be expelled for their inconvenient beliefs or identities, the question of who is excluded and what views are up for debate is fundamental to a democratic order. This means that we will have first-order conflicts about the actual content of political decision-making, but also that we will have second-order conflicts about the process, content or subjects of the first-order conflict. If we aren’t careful, this easily becomes infinitely regressive.

As Amy Allen in The Power of Feminist Theory (1999) and Catherine Eschle in Global Democracy, Social Movements, and Feminism (2001) argue, domination can arise through what sorts of reasons are broadly accepted into public discourse and from whom those reasons can be heard. That is, what reasons are accepted and who is understood to be the proper person for providing those reasons are both ways that organisations can affect domination. Take, for instance, an imagined feminist organisation composed solely of cis women. If the organisation specifically excludes trans women, then it is imposing a certain kind of domination. Similarly, if the organisation’s members refuse to hear concerns about the relationship between anti-trans, patriarchal and homophobic political tendencies, there’s a kind of domination operating. When a group structures who and what will be considered part of its legitimate political processes, it can unjustly exclude. It comes as no surprise that these unjust exclusions often replicate their society.

To agitate a conflict, from within an organisation, can be an attempt at making the organisation more democratic in so far as it ceases with unjust exclusions. In the absence of a conflict, the organisation would fail to fulfil its values and probably fail to achieve its goals – lacking, as it does, a clear view of the nature of the problem at hand. Conflict, then, can be about ending unjust exclusions, or it can be a substantive disagreement about the goals or tactics that a group aims to undertake. In either case, the conflict isn’t just about a psychological draw-and-repulsion relationship with other human beings (as it is so often dismissed), but rather it is about something concrete with real stakes for those involved. If they lose the fight, they lose something substantive, not just a psychological sense of success.

One cannot simply remain unchanged by one’s experiences with others

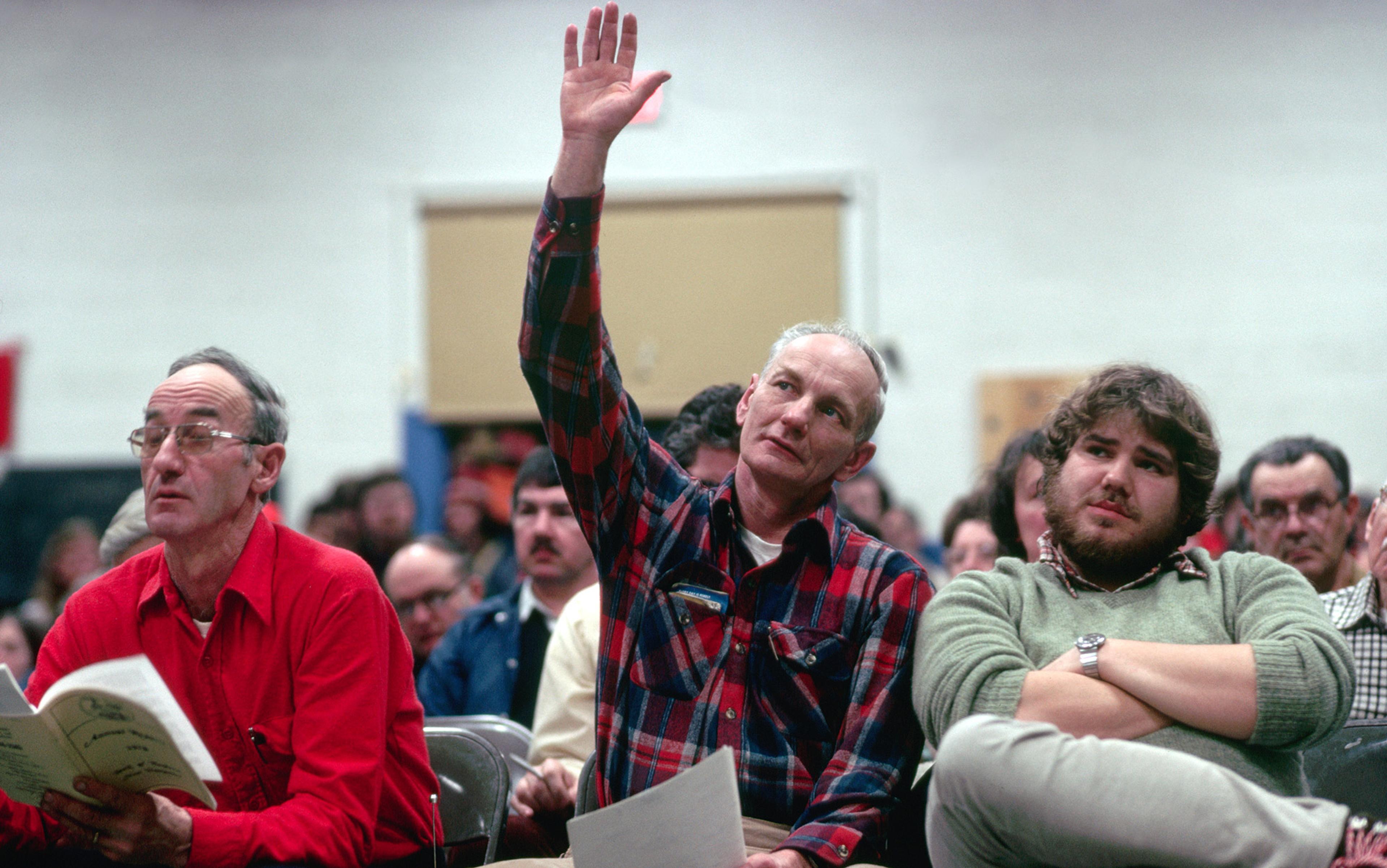

It is this realistic type of conflict that is fundamental to democracy, understood not just as a structure for political institutions, but as a social and political process. When people come together in groups to achieve some goal, democracy functions where people can contest their own exclusion, the formative values or substantive goals of the organisation, and the means by which the group intends to achieve such goals. Substantive conflict is necessary because of the inescapable pluralism of human beings, but also because of a history of the structure and influence of systems of power designed for structural domination. This makes it likely that groups will reproduce systems of domination that exist in the wider world. In that way, conflict becomes part of the process of building a future world that is less exclusionary and less dominative.

People believe conflict will tear a group apart specifically because they run together realistic and non-realistic forms of it. We struggle to separate out name-calling from more substantive demand-making. Often, this is because substantive demand-making also comes along with at least the appearance of name-calling. The name-calling, then, becomes a reason to deny the demand. White Americans, for instance, tend to see ‘racist’ not simply as an accurate identification of a feature of the world, but as a coded slur for white people. Attempts at racial justice, then, come to be seen as non-realistic conflict where people just want the pleasure of smearing someone as racist, rather than an end to a specific iteration of racist subjection.

The way that realistic conflict functions in democratic life is that it can eliminate exclusions, hone and develop positions for the group, and bring about the change to individuals that makes them suited for living among each other. Excluding conflict from democratic life, then, not only risks giving into authoritarian tendencies to exclude, expel or annihilate, but also fails to recognise the subjective changes that are part of participation in democratic life. Fundamentally, atomised versions of democratic life fail to see how participation in the collective project of democracy also affects changes on us, via the process of conflict. One cannot simply remain unchanged by one’s experiences with others (who present new challenges and new information). This feature of conflict is the function of integration that is necessary for democratic legitimation.

One of the positive features of conflict is that it changes us, shapes us, moulds us. Participating in conflict over the things that matter to our shared lives gives us an investment in each other and the project of living our lives together, rather than living them merely near each other. While there is nothing necessarily democratic about conflict, there is a clear antidemocratic tendency, in both liberal and authoritarian thought and movements, to eliminate conflict.