As part of a recent walk across England, I entered the Chilterns from their western edge, above the Thames Valley. Because the beech trees were climbing with me up the side of the hill, they had to grow even higher to reach the sunlight. The effect was spectacular: the tall beeches disappearing for nigh-on 100ft up into the canopy, the great height of the tree trunks accentuated by the delicacy and smallness of the beech leaves floating like maidenhair. With the large ferns guarding the entrance to the wood, the effect was Amazonian. Not for the first time, I reflected on how exotic we would find a horse chestnut in flower, or a beech forest in spring, if we came across them in Brazil rather than Buckinghamshire.

A forester I met in the woods told me that we might be the last generation to enjoy these Chiltern beeches. Grey squirrels have become so common, and attack the young saplings so viciously, he said, that there is virtually no regrowth. When the last of the great trees reach the end of their natural span and come tumbling down, the change will have far more impact than any high-speed train.

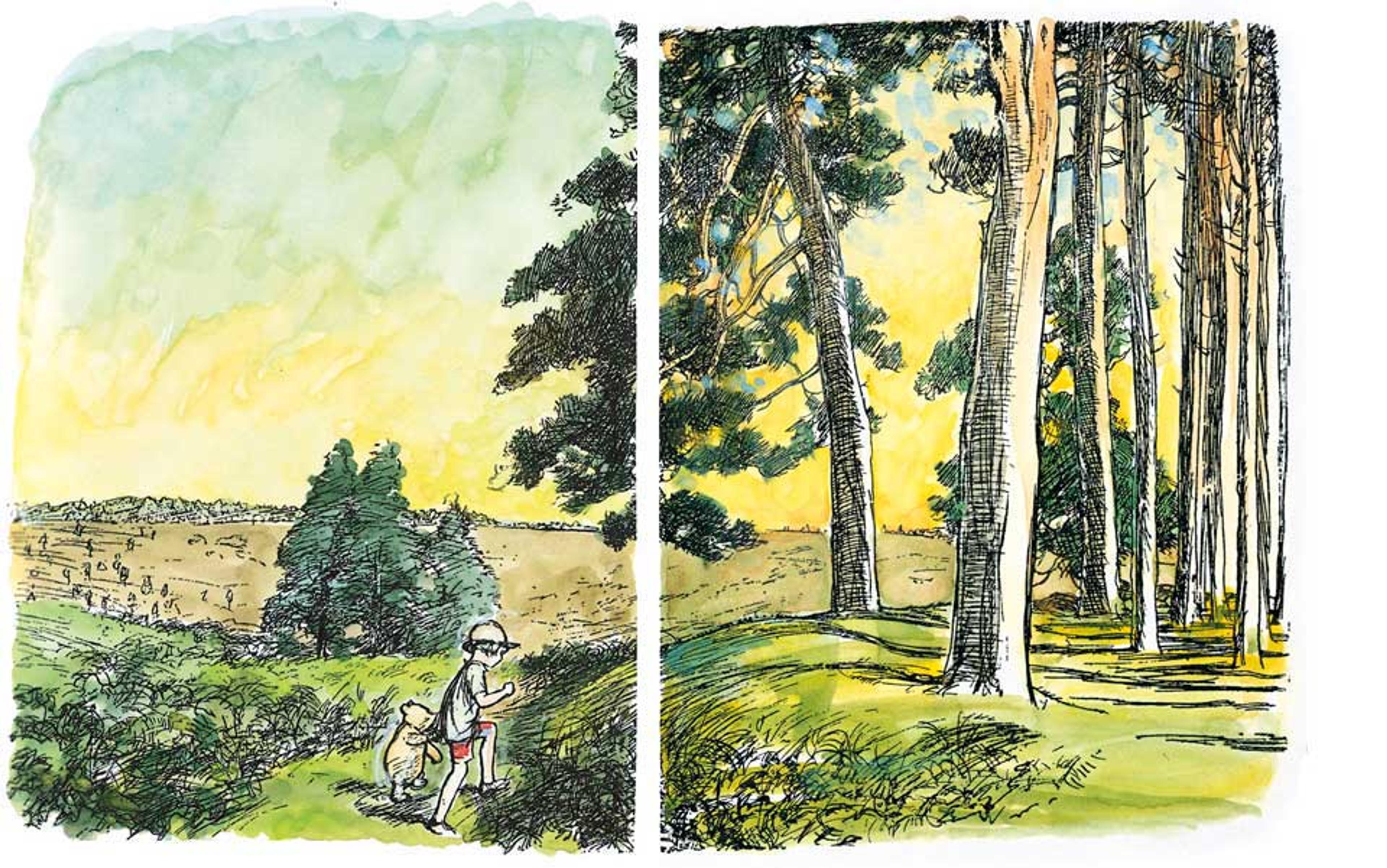

The loss of woodland will not just be a physical one. The beeches of the lower Chilterns were the Wild Wood into which Mole and Ratty strayed. They remind us of an older English past that has become heavily mythologised and distorted — like the knights on the Grail Quest who periodically disappeared and were lost in the trees — and yet depends on the perception that much of England was forested for the greater part of its history. A perception that is wrong.

Before consulting the archaeological research, my assumption — widely shared, I suspect — was that England was largely wooded until the arrival of the Romans. Prehistoric Britons might have made a few inroads into the densely forested valleys, but preferred the wide-open expanses of Salisbury Plain or other high, treeless places such as Dartmoor or the Berkshire Downs. The Romans cleared some lowland areas for their settlements and built connecting roads. With the arrival and gradual domination of the Anglo-Saxons during the Dark Ages, more woodland was slowly lost, and a pattern of villages emerged, ready for the Domesday Book to record after the Norman conquest.

There is an undercurrent of regret running through our history

This understanding has now been shown to be wholly inaccurate. Much of England had been cleared as early as 1000 BCE, some two millennia beforehand. The Bronze Age saw intensive farming on a scale that we are only just beginning to appreciate. As Oliver Rackham puts it in The History of the Countryside:

It can no longer be maintained, as used to be supposed even 20 years ago, that Roman Britain was a frontier province, with boundless wild woods surrounding occasional precarious clearings on the best land. On the contrary, even in supposedly backward counties such as Essex, villa abutted on villa for mile after mile, and most of the gaps were filled by small towns and the lands of British farmsteads.

Rackham describes the immense clearance undertaken during the Bronze Age, boldly claiming that ‘to convert millions of acres of wildwood into farmland was unquestionably the greatest achievement of any of our ancestors’. He reminds us how difficult it was to clear the woodland, as most British species are difficult to kill: they will not burn and they grow again after felling. Moreover, in his dry phrase, ‘a log of more than 10 inches in diameter is almost fireproof and is a most uncooperative object’. The one exception was pine, which burns well and, perhaps as a consequence, disappeared almost completely from southern Britain, the presumption being that prehistoric man could easily burn the trees where they stood: the image of pine trees burning like beacons across the countryside is a strong one. Only with the Forestry Commission in the 20th century were large numbers of conifers reintroduced.

Some Bronze Age woodland was naturally kept and managed for what it could provide: timber for building materials, smaller wood and shrubs for fuel, acorns for pigs (which were often turned loose into the woods in autumn), hazel and other trees suitable for coppicing. But this was small-scale. When the Domesday scribes recorded a relatively low level of English woodland — a much lower proportion than, say, modern France enjoys today — this was not a recent development, but the way it had been for millennia.

The idea that England 3,000 years ago was already as suburban as the outskirts of Basildon has not been absorbed into the popular consciousness. Nor will it ever be readily, for we suffer from what might be called Sherwood Syndrome: the need to believe that much of England — most of England — was both wild and wooded until modern history ‘began’ in 1066, or indeed stayed so until much later; and that these ancient forests were the repository of ‘a spirit of England’, the Green Man, that could be summoned at times when we needed to be reminded of our national identity; where Robin Hoods of all subsequent generations could escape, where the Druids gathered their mistletoe from the trees, where the oak that built our battleships came from.

The myth panders to our need for a sense of loss. There is an undercurrent of regret running through our history. A nostalgia for what could have been: the unicorn disappearing into the trees; the loss of Roman Britain; the loss of Albion; the loss of Empire. We are forever constructing prelapsarian narratives in which a golden sunlit time — the Pax Romana, the Elizabethan golden age, that Edwardian summer before the First World War, a brief moment in the mid-1960s with the Beatles — prefigure anarchy and decay. Or the cutting down of the forest.

One only need look at the near-ecstatic reception given to Danny Boyle’s Olympic rendition of our ‘green and pleasant land’, complete with shire culture and hobbit mounds, to see how easily history elides with mythology. Britons are supremely comfortable with that blurring — with a mythic dimension that adds gravitas to our self-understanding, and that imbues the land with a kind of enchantment, a magical aspect that is echoed in our narratives of how we came to be a nation, but is as illusory as the Arthurian lake from which the Lady’s hand emerges to grasp the sword.

The idea of England as a wild and wooded land until the arrival of the Romans is a powerful one. Of course, the landscape that Bronze Age travellers surveyed in 1000 BCE, as they travelled the Icknield Way along the Chilterns ridge line, around the time the White Horse of Uffington was carved, would have been different. No Swindon, Didcot Power Station or M4 motorway, for a start. But a cultivated system of fields and pastureland was already there, albeit in a different formation.

What the work of archaeologists over the past few decades suggests is that we possessed the land very early — that England was shaped long before the arrival of the Romans, whose occupation can be seen as a brief, anomalous interlude interrupting the continuity of British history.

How appropriate then that the Bronze Age should be defined by its bronze axes, which were both the principal units of currency (large stashes of them have been found buried in fields) and the means by which the trees were felled. When the oak tree at the centre of Seahenge was examined and found to have been cut down in 2049 BCE, during the early Bronze Age, the marks from some 50 different bronze axe-heads could be distinguished.

What we have always been good at is not hiding in the forest but cutting it down.

Hugh Thomson’s The Green Road into the Trees: An Exploration of England is published by Preface.