Green men they are called; or, less poetically, ‘foliate heads’. They captivated me from a young age, and I have been collecting them, on and off, for years. I have more than a dozen dotted around my house now. I have line drawings, paperweights, even a candlestick with leaves winding their way up the shaft. There is a wooden beam on the ceiling of the room where I work that has eight green men strung along it. Two of them are replicas of stone bosses from the ceiling of Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland; another is a wooden copy of a foliate head from the choir stall of Lincoln Cathedral. This year saw my 40th birthday, and I am toying with the idea of having a green man tattooed on my shoulder to commemorate the occasion.

I don’t want to give the impression that I’m obsessed. Obsessions are constant and all-consuming, whereas my interest in the green man is sporadic but ongoing. But whenever I go into an old church, the first thing I look for is a foliate head. It’s like a treasure hunt. You might find your treasure hiding among the choir stalls or the bench ends, in the stained-glass windows, in roof bosses, or as gargoyles on the guttering. But you will find it, surprisingly often. When you do, it is like finding a golden egg.

What is this thing? Its origins and meaning are obscure and probably now unknowable, which is one of the attractions. Why do we find, carved in old Christian sanctuaries, this strange, even daemonic, and very un-Christian symbol?

There are plenty of hypotheses, and it depends on whom you talk to. Those inclined towards paganism like to claim that green men are relics of pre-Christian religions that have been incorporated into churches. I have heard, variously, that the green man represents the spirit of the greenwoods, the rebirth of nature, a rebellion against Christianity, or a symbol of the constancy of nature. Everybody who knows the green man has their favourite theory about what he is and why he is there.

Here is mine, which has no more or less basis in fact than any other. It begins nearly 1,000 years ago, on the best-known date in English history.

The year 1066 was the first and the last time that the kingdom of England was comprehensively conquered. The battle of Hastings, in which most of the English ruling class and its fighting men were annihilated, is well-known enough not to need any explanation here. King Harold II was killed, and Duke Guillaume of Normandy (later Anglicised to ‘William’) claimed the English crown, despite having no serious claim to it.

If school history classes are anything like they were when I was a boy, the battle of Hastings will be taught in some detail and its aftermath will barely be mentioned. But Hastings was only the beginning of the Norman campaign to conquer England. For ten years, the natives fought back against the invader’s forces. There was a full-fledged guerrilla insurgency, reminiscent of the French resistance or the Viet Cong. Few people today know much about it and, until I began researching it three years ago for a novel set in the period, I didn’t either. But it has arguably shaped the England we still live in.

After Hastings, Guillaume expected the remnants of the English elite to grant him the crown. Instead, the Witan, or high council, gathered in London and acclaimed a new king: not the Duke, but Edgar, Edmund II’s 14-year-old grandson. Until the Normans introduced the concept of automatic hereditary monarchy to England, kings were elected by the Witan. And this one, even after Hastings, refused to elect Guillaume.

The Duke dealt with this problem in characteristic style: with violence. He marched his army up through the south-east, burning, looting and raping. He circled London, burnt Southwark to the ground and then marched west, brutalising the populations of Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Middlesex, and Hertfordshire. Soon enough, the Witan relented. They had no means of resisting what the Normans had brought. On Christmas Day, Guillaume le Bâtard — William the Bastard, as his own people knew him — was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey.

Within a decade of the conquest, the number of English people in positions of high authority could be counted on the fingers of one hand

What did Guillaume expect from England, and what did the English expect from him? It was not the first time a foreign king had seized the English throne; only half a century earlier, the Danish king Cnut had been crowned after a similarly successful invasion. Cnut had made changes to the way England was governed, but he hadn’t sought, or needed, to hold its people down by force. The Danish king’s takeover had been a transition of elites, which had barely affected the mass of people. Perhaps the English thought that, after the most terrifying year in living memory, this latest foreign lord might turn out to be a new Cnut: stern but benign, maybe even their protector.

They were soon to be disabused. One of the first laws enacted by Guillaume, in January 1067, declared that all the land in England belonged to the crown. All who held land, from the highest lord to the lowest peasant, now held it on sufferance from him. This was a revolution from the top, and it allowed Guillaume to pay back the mercenaries who had made up much of his invading force by parceling out the nation’s acres to them. Then he increased taxes, several times (the Domesday Book was a tax-collector’s manual). He also appointed his friends, relatives and lieutenants to the highest offices in the land. Within a decade of the conquest, the number of English people in positions of high authority could be counted on the fingers of one hand.

At this point, the fires of rebellion began to burn. The Normans had tied down the south-east of England, but much of the rest of the nation was yet to be won. The sons of the late King Harold made raids on Devon and Cornwall from their refuge in Ireland. Edgar, the almost-king, fled to Scotland and won the protection of King Malcolm. On the Welsh borders, an outlaw known as Eadric the Wild waged a vicious guerrilla war.

On the opposite side of the country, in Lincolnshire, a dispossessed landowner named Hereward put up an astounding display of bravado, holding out on the fen isle of Ely with an army for years and slaughtering Normans by the dozen. And all the time, all over the nation, bands of outlaws took to the woods, the marshes and the wastelands, with the tacit support of local populations, emerging to harass, harry and assassinate the occupying forces.

In 1069, matters came to a head. The Earls of Mercia and Northumbria raised armies, joined forces with young Edgar, Malcolm of Scotland and some of the Welsh princes, and declared war on Guillaume. The rising of the north, as it became known, was the best chance the English had to repel the new king, but it was a disaster. Guillaume took his mounted knights north, building castles as he went, and destroyed those parts of the army of resistance that hadn’t fled on news of his approach. To make sure that there would be no further hiding place for rebels, he embarked on the notorious ‘harrying of the north’, obliterating every house, every field, every animal, between York and Durham. Chroniclers of the time reported that survivors were reduced to selling their children into slavery, or digging up graves and eating the corpses.

Those kinds of memories don’t easily fade. Orderic Vitalis, the contemporary Anglo-Norman historian, wrote that ‘the English groaned aloud for their lost liberty and plotted ceaselessly to find some way of shaking off a yoke that was so intolerable and unaccustomed’. Six hundred years after the conquest, during the English Civil Wars, radicals still drew on the concept of this ‘Norman Yoke’ to contextualise the oppression meted out by Charles I, descendant of Guillaume. The romanticised notion of a free Anglo-Saxon kingdom remained popular with the Victorians. History, like any other academic discipline, has its fashions, and these days, partly in reaction to Victorian bombast, the idea of a Norman Yoke is sniffed at in the academies. Today, like good post-colonialists, we like to talk of integration and migration, not suppression and resistance.

But I wonder. It seems to me that legacies of 1066 remain with us. Take that law enacted by Guillaume in 1067. In Anglo-Saxon England, the idea that one man — the king — literally owned the entire landbase of the nation would have been unthinkable. Today, it remains a legal reality: England is still owned, as a whole, by the Crown. The hereditary monarchy introduced by the Normans remains too, and the French concept known as ‘primogeniture’ — in which estates are inherited wholesale by the first-born son, rather than parceled out between children as was more common in Anglo-Saxon England — is still alive as well.

What would have happened if things had gone the other way on the hill outside Hastings, on 14 October 1066? Who would we be now?

Tie these threads together and follow them, and things become fascinating. Today, Britain is the country with the second most unequal distribution of land on Earth, after Brazil. More than 70 per cent of the land is owned by fewer than two per cent of the population. Much of this is directly traceable to Guillaume, whose 22nd-great-granddaughter sits on the English throne today.

Then follow the thread further, and ask yourself whether the development of early modern capitalism in England would have been possible without that concentration of land, and therefore power and wealth. What about the consequent empire? Did the industrial revolution begin in England because that funnel of power and money made it possible? Or what about class, which is directly connected to all of those things? We are still one of the most socially and economically stratified countries in Europe. In today’s England, the rulers still drink wine and the ‘plebs’ still drink beer, just as they did in 1066. The peasants still keep their heads down, too, mostly — whatever the wine-drinking class gets up to with their money or their votes.

What would have happened if things had gone the other way on the hill outside Hastings, on 14 October 1066? Who would we be now? What language would we speak, what land would we inhabit, and what world? What would be carved in our churches, and who would those churches hymn? History never answers questions such as these, but every generation gets its chance to ask them.

All this leads us, in a roundabout fashion, back to the green men. When I was younger, I used to love visiting old Norman churches. As a history nerd, I knew the difference between a Romanesque and a Perpendicular window, and could trace the development of an old church by examining the style of its buttresses and the size of the yew trees in the churchyard. I loved the carved doorways, the thick stone columns and the damp, restrained silence.

These days, I have a different relationship with Norman churches: I see them as symbols of oppression. The Normans made a point, after they had consolidated their takeover, of tearing down significant English buildings and replacing them with Norman equivalents. Saxon churches, often made of wood, were replaced with these heavy, squat monuments in eternal stone. A Norman church, to me now, is the equivalent of a motte-and-bailey castle: not simply an interesting old building, but the mark of a conqueror spitting in the face of the conquered.

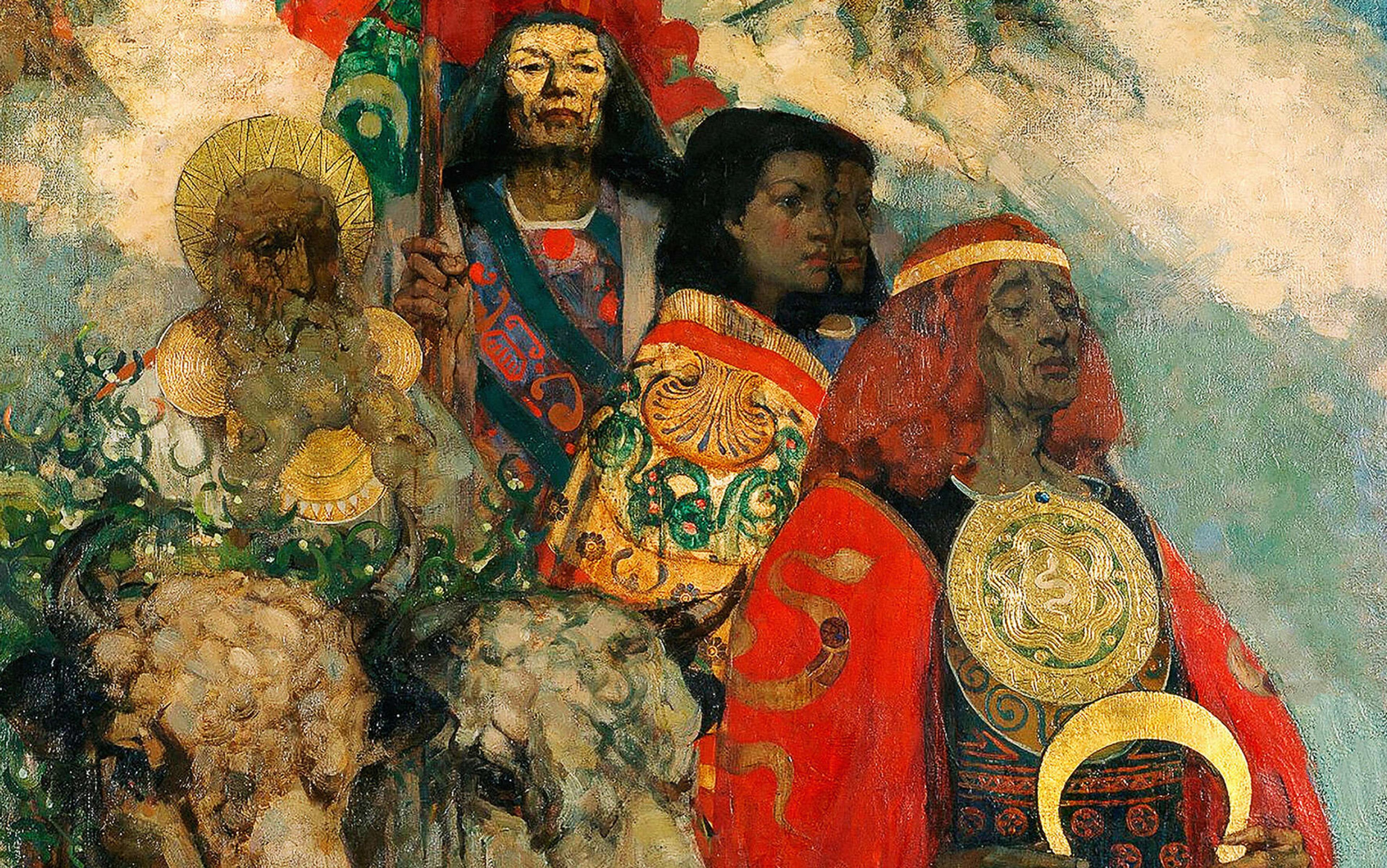

Perhaps this was how they were seen by the English at the time. The Normans called the guerrilla movement that resisted them after 1066 the ‘silvatici’ — the men of the woods. The English, it is said, called them the same thing in their own language: green men. In that greenwood rebellion against unwanted masters, we perhaps see the origins of the Robin Hood legend — and of those carvings in the old churches. What would you do if you were an English stonemason in the 1070s, required to help construct an alien church by new masters you despised? How would you show your loathing of them without attracting a penalty? Perhaps you would carve the face of a green man inside the church: perhaps you would bring the spirit of the silvatici into the temple of the enemy. It could be that what adorns the roof beam of my room is not a wistful old nature spirit, but a symbol of resistance to the crushing of a people.