One Friday evening in March, my husband walked into the house and said: ‘There was a death threat. A defendant in one of my cases.’

My husband is in law enforcement. He helps put bad people in jail for a really long time. He’s been doing it for 20 years. One might think he would have had a death threat before, but he hasn’t. Apparently, it’s not that common.

We discussed the details of the threat, how the defendant knew what kind of car my husband drove and that he’d said he would hire someone to do the deed.

That night, I was able to fall asleep but it took a while. The following night, I had two drinks and fell asleep fairly quickly, but at 2am my eyes sprang open and my heart was pounding. I lay in bed for hours, thinking every creak and thump I heard was someone trying to break into our home. By Sunday night, I’d gone with my son, a toddler, to the home of a neighbour, and then detectives recommended we leave town altogether. My husband stayed behind. Even in our weekend home miles away, I feared the killers were lurking outside, and at night the heart-pounding fear returned.

I felt like a coward, the kind Ernest Hemingway wrote about with contempt, while my husband, the real target, slept soundly and went to work, unfazed. Yet it turns out that the difference between us is not moral but fiercely biological, the result of the well-known fight and flight response, which revs the hormone epinephrine, increasing blood flow in the body and focus in the brain, all the better for an accurate hair-trigger response. Matthew Frank, a senior research associate at the University of Colorado’s department of psychology and neuroscience, says that the immune-suppressing hormone cortisol, which induces a kind or torpor, can also be involved, causing some people to freeze. ‘We are at the mercy of our biology, which can preserve our lives,’ Frank notes.

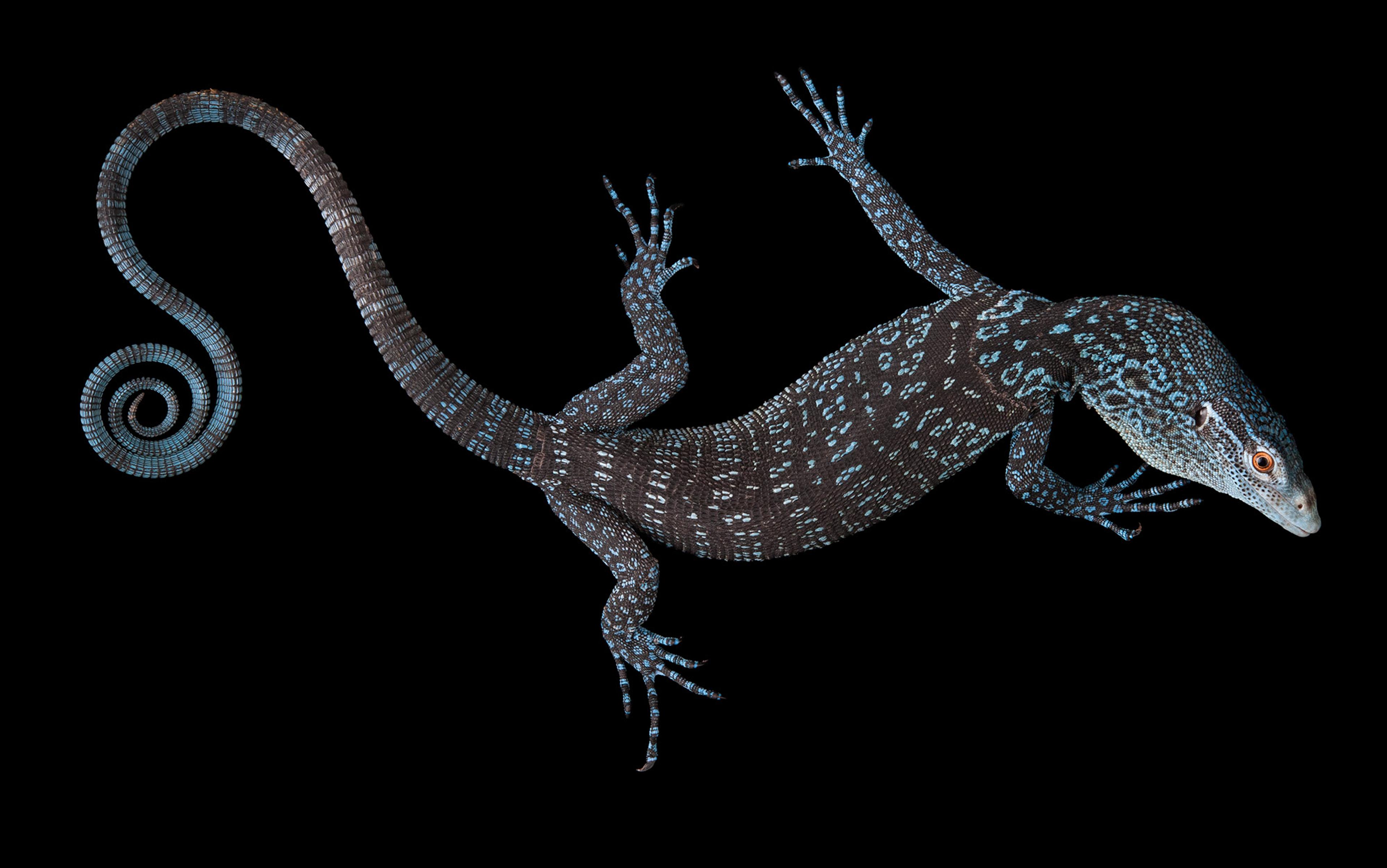

It makes sense that in the ‘red zone’ you fly on automatic, adds Brooke Deterline, a leadership and courage consultant who works with corporations. After all, the desire to be fearless goes out the window when cognitive thinking is impaired. In Deterline’s workshops, people are instructed to exhale for twice as long as they inhale, lowering cortisol in the body and promoting clear thought. ‘When we’re flooded with cortisol, we’re in the reptilian brain. We don’t have access to our natural compassion and higher functioning,’ Deterline explains. In the days of the hunter gatherer, the response made sense. ‘You shouldn’t be contemplating anything if you’re about to be eaten by a bear.’

There is method to the madness, David Baldwin, an Oregon-based trauma psychologist, has found. In the tumult of the fight response, blood moves more to the jaw and arms, while in the flight response, it moves more into the legs. We can change our minds if the response we picked isn’t working, he explains. In fact, his recent paper, published last year in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, lists five reactions in all – freeze-alert; flight; fight; freeze-fright; and collapse – and we experience them in just that order, depending on the level of threat.

The system is flexible, and automatic: severe stress causes the thinking part of the brain, the cortex, to go offline, Baldwin says, while the primitive brain takes control. After an explosion from a terrorist attack, for instance, if fleeing is an option, we might do that first. If we think we can win, we might fight. When neither fight nor flight seems like an option, we might stay frozen or even collapse, just as someone might do in a bear attack. If the animal thinks you’re dead, he might decide you’re rotten food and leave you alone. ‘Immobility doesn’t require much cognitive function,’ Baldwin notes.

While I fixated on the fear that I was being stalked in the country, my husband stayed in town. He went to work, went for jogs, and slept easily at night. I suggested he come to the country house, but he declined. ‘I don’t want to make you feel uncomfortable.’

‘You won’t,’ I said. He would.

The second night in the country house, I drank martinis hoping it would help me sleep. But I woke up at about 3am, chilled by that thought that the killers had put a GPS tracking device under my car and followed me up to the weekend house, assuming my husband was there. I heard the wind howling, the leaves blowing, and thought the killers were trying to get in. I thought about a gang retaliation, where shooters had targeted the window of the wrong home, murdering the wrong guy. Could these killers mistake me for my husband and murder me in my sleep?

I finally fell asleep at about 4:30am and had a nightmare. I had been sleeping on my stomach and, in the dream, someone came into the house and grabbed my arms from behind so I couldn’t move. I turned around and looked at the person’s face and said: ‘What are you doing?’ It woke me up.

About half an hour later, my son woke up and wanted his pacifier. I gave it to him and brought him into my bed. As I tossed and turned, I imagined the killers thinking my son’s body was that of my husband and shooting him through the window. I barely slept.

I vowed to take my car to a mechanic that afternoon to see if there was a GPS device on it.

‘I know, I know, they’re not after me,’ I told my husband on the phone that night. ‘But they don’t know you’re not with me.’

What a loving wife.

I was deep in Deterline’s red zone, yet why would members of the same species react so differently to the same threat as my husband and I did? Why hadn’t evolution found one of those tendencies more useful, and made the other obsolete?

‘The early bird gets the worm, but the second mouse gets the cheese’

Precisely because there are advantages to each, says the German psychologist Lars Penke of Georg August University in Göttingen. In some environments, it might be more beneficial to be fearful – or ‘shy’, in psychological parlance – while in others it could be better to be fearless, or ‘bold.’

The psychologist Steven Pinker once described Penke’s theory as: ‘The early bird gets the worm, but the second mouse gets the cheese.’ An environment that has worms in some parts and mousetraps in others could wind up with a population of ‘go-getters and nervous nellies,’ Pinker explained in 2009 in The New York Times Magazine. Everyone gets some food.

Shyness or boldness? The strategy is subject to cost-benefit analysis of the evolutionary kind: which trait increases my chances of survival or my chances to reproduce? What would be most adaptive is switching from one response to the other, depending the situation, but our underlying biology cannot switch back and forth that quickly, Penke says. If your body is set up to react quickly to danger, it’s difficult to change to a more passive strategy fast enough to actually survive.

Individual fight or flight strategies often align with personality, especially the ability to brush off social rejection. In a study from 2008, Penke and colleague Jaap Denissen, now at Tilberg University in The Netherlands, likened social navigation to surviving in the jungle – except here, fitting in enables survival while expulsion from the group is the social equivalent of death. The more a person can withstand social rejection, the more courageous she may be, but the more she risks exclusion.

‘Maybe you can’t have cowards unless you have brave individuals they can hide behind’

In natural populations, we see a continuum of these traits, in part because of trade-offs to each. Maybe boldness is bad when it comes to survival, notes University of Illinois in Urbana biologist Alison Bell, but better in terms of finding mates. It could be good to be shy around predators – you won’t get eaten. But if you’re not aggressive enough to get a lot of food, you might have trouble procreating and passing on your genes.

In fact, the existence of a spectrum from cowardice to bravery helps a species survive. A left-handed pitcher in baseball will flourish specifically because there are so many right-handed pitchers. Likewise, some birds obtain food by hunting for it while others simply steal it from the hunters. Those that steal need birds that will hunt, lest the thieves should have no one to rob.

‘Maybe you can’t have cowards unless you have brave individuals they can hide behind,’ Bell says.

Brave people might be built differently, according to recent studies. In one well-documented case, a woman known as ‘SM’ had a damaged amygdala, a part of the brain known for processing fear. It has made her absolutely fearless – a state especially pronounced because her rare condition, Urbach-Wiethe disease, had deposited calcium in her brain, causing lesions on both sides.

In a study published in 2011 in the journal Current Biology, researchers exposed SM to live snakes and spiders, took her on a tour of a haunted house, and showed her emotionally evocative films; she was unwaveringly calm. She also lacked fear in her day-to-day life, even when she was held up at gunpoint, then at knifepoint, and was almost killed during a domestic incident.

Interestingly, when researchers tested her again in 2013 and had her inhale CO2, or dry ice fumes, an experience that in ordinary people brings about a feeling of asphyxiation, SM’s response was utter panic. This excessive response showed clearly that the amygdala is not the only part of the brain that processes fear. That made sense in light of findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2009, showing that rodents could be rendered fearless when scientists neutralised a different part of the brain, the hypothalamus. Human circuitry is much the same.

when the bullied mice were adults, they themselves were more aggressive and prone to violence

SM sustained brain injury from a disease, but fear and fearlessness are often inborn. Earlier this year, scientists at the Stanford University school of medicine found that some people might have a propensity for anxiety, depending on how their amygdala had developed during childhood. In the study, which appeared in the June issue of Biological Psychiatry, researchers recruited 76 children aged between seven and nine, a time when anxiety-related traits first begin to appear. Scanning their brains with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the researchers found that children with high levels of anxiety had larger amygdalas and increased connectivity between brain regions responsible for attention, emotion perception, and regulation. The results were so consistent that researchers were able to develop an equation predicting a child’s anxiety level based on the brain scans.

Environment plays a role, too. Someone exposed to violence or abuse is likely to respond to danger differently from someone who has not. Cornelius Gross, the senior scientist with the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Italy, showed this by taking young mice before they’d been weaned and repeatedly exposing them to an aggressive male mouse every day for 10 minutes. Two months later, when the bullied mice were adults, they themselves were more aggressive and prone to violence.

‘Early exposure to violence makes you more of a bully,’ and conversely, less timid, says Gross.

How we respond to fear is actually a complicated algorithm involving our biology and our experience. Just last year, the neuroscientist Bo Li and colleagues at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York discovered a connection between experiential memory and fear: a set of ultralong neurons stretch from the amygdala directly to the midbrain’s periaqueductal gray (PAG), which orders the automatic flight or flight response. ‘If the connections are too strong,’ says Li, ‘it could induce a greater sense of fear.’

I finally took the car to a mechanic and explained that I wanted it checked for a tracking GPS – maybe the killers were on my trail. He had five guys look at the car and they found nothing. I was relieved and thought I might finally get some sleep. But by the time we got home, I started thinking that the killers didn’t need a GPS device to track us. They probably followed us out there the old-fashioned way.

The following day, the detectives investigating the threat called the local police near our country home to ask them to keep an eye on our property. That night, someone banged loudly on the door. I spotted a badge through the window. My heart was pounding.

‘Just wanted to let you know we take these things seriously,’ the officer said.

That night, I tried to sleep on the floor of my son’s room, thinking that, if I was with him, I might feel more comforted. But as I lay on the floor, I could see a police car’s flashing red lights go by our house periodically, and it unnerved me. I associated those lights with blood and murder, not security.

I got up from the floor and lay down on the living room couch and turned on an old episode of Mad Men, so that I wouldn’t hear any random noises outside. It was after midnight, and I fell asleep after about 10 minutes but woke up again when the episode ended. I put on another episode and again fell asleep after a few minutes but again woke up when the show was done. I did this over and over all night until the sun started to come up.

The next morning, I told my sister about sleeping on my son’s floor for part of the night.

‘Like a mama bear,’ she said.

‘I wish. No, I thought sleeping on his floor would make me feel more sheltered. My room, with all the windows, just felt so exposed, like anyone could walk right up on the deck and come right in,’ I said.

The following night, my husband called and said: ‘There was no plot. They questioned everyone involved, and there was no plot in place. There never was.’

how I respond to danger was decided for me long ago, a consequence of my upbringing or a genetic flaw

The following morning, I packed up the car and my son, and I drove home – relieved but unconvinced.

A few days later, a man in a grey Honda wearing a nylon do-rag on his head drove by our house. Minutes later, he drove by again. He drove slowly by our house about seven times, each time with his window opened, his eyes fixed straight ahead, as if he didn’t dare turn his head to look at me. One time, he tried to parallel-park the car across the street from our house and pulled in and out several times into what was quite a large spot before giving up and driving off. I wrote down the licence plate and called my husband. It turns out the man lived around the block and was practising driving and parallel-parking for his road test.

Several months later, I was at my desk when I got an email from my mother, who was on a cross-country trip with her boyfriend in an RV. She was writing from an Air Force base in Nebraska, where there were thunderstorms, hail and gusts of wind so severe the National Weather Service had issued warnings. My mother said she couldn’t sleep and had sat up half the night, panicked, watching the Weather Channel. She was so afraid the motorhome would blow over, she had a bag packed with all their medications, cell phones and iPads, and left her clothes at the foot of the bed in case she had to make a run for it to the campground’s shelter.

I closed the email and thought that how I respond to danger is something that was decided for me long ago, a consequence of my upbringing or, like a birthmark, a genetic flaw. Or maybe it’s not a flaw at all. I might never be the early bird who gets the worm, but I’ll definitely get my share of cheese. And when I do, I’ll share it with my husband, because I owe him that much.