Today, I filled out our US Census form. The dead are not counted. My girl does not count. I suppose that’s why I must MAKE her count somehow. Now that I’ve failed my job of keeping her alive, of growing her up, my job is now to make her short life mean something. This is the work of the bereaved parent, I suppose. Our drive to keep going is really our desire to do our children’s unfinished work.

I wrote these words almost 10 years to the day since my 17-year-old daughter was killed by a distracted driver. In the hours after her death, her stepfather and I began conceptualising an organisation in our daughter’s name. We felt strongly – almost instinctively – that we had to make some good from our tragedy, to make her life – and her death – count.

Gracie was so much more than the victim of a fatal car crash but, undeniably, she was that, too. This fact carried a near-magnetic pull. Wasn’t it my job to prevent more senseless deaths like hers? A resounding yes pounding in my chest, more questions churned: how do I carry her story forward? How do I honour her? I wrestled mightily with ambivalence about what to do. I was wary about engaging in safe-driving advocacy because, if we went that route, our daughter’s memory would be reduced to that of a girl who died in a car crash. I also worried that repeatedly revisiting her death would keep me in a painfully dark and ugly place, compounding my daily suffering.

Around this time, I attended a survivors’ panel organised by the Massachusetts Office of Victim Assistance. Each panellist offered suggestions for coping with the violent death of a loved one. One of the panellists – the brother of a murdered young man – paused during his remarks, sighed heavily, and said: ‘And whatever you do, don’t start another fucking foundation. Let the professionals do that. Your job is to take care of yourselves.’ His emphatic statement tapped right into my ambivalence.

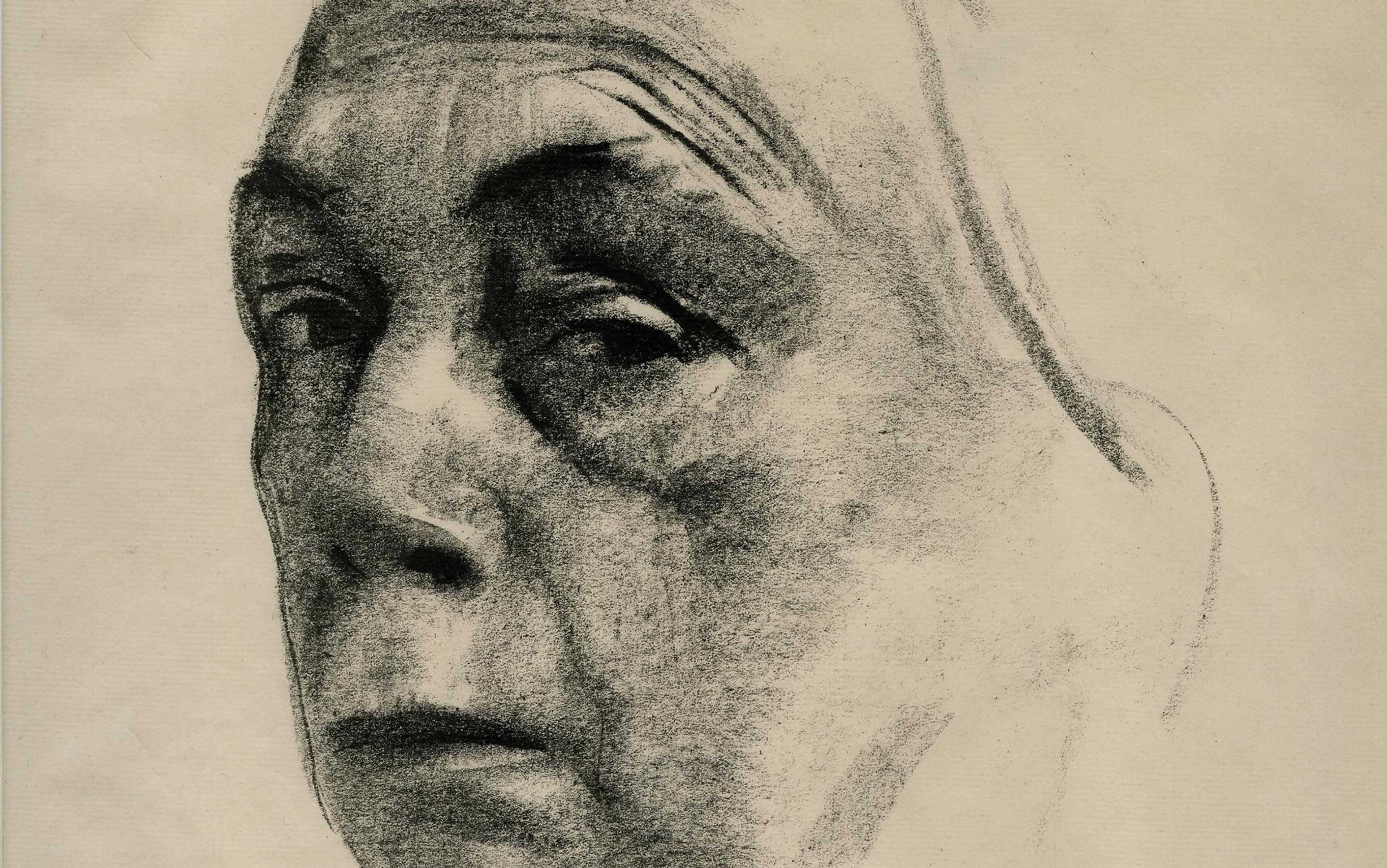

His words offer one way to think. The bereaved activist mother Mamie Till-Mobley shows us another: when her Black teen son Emmett was abducted, tortured and lynched in Mississippi, she insisted that his casket remain open so that ‘the world [can] see what they did to my baby.’ Her act is often credited with launching the civil rights movement in 1955.

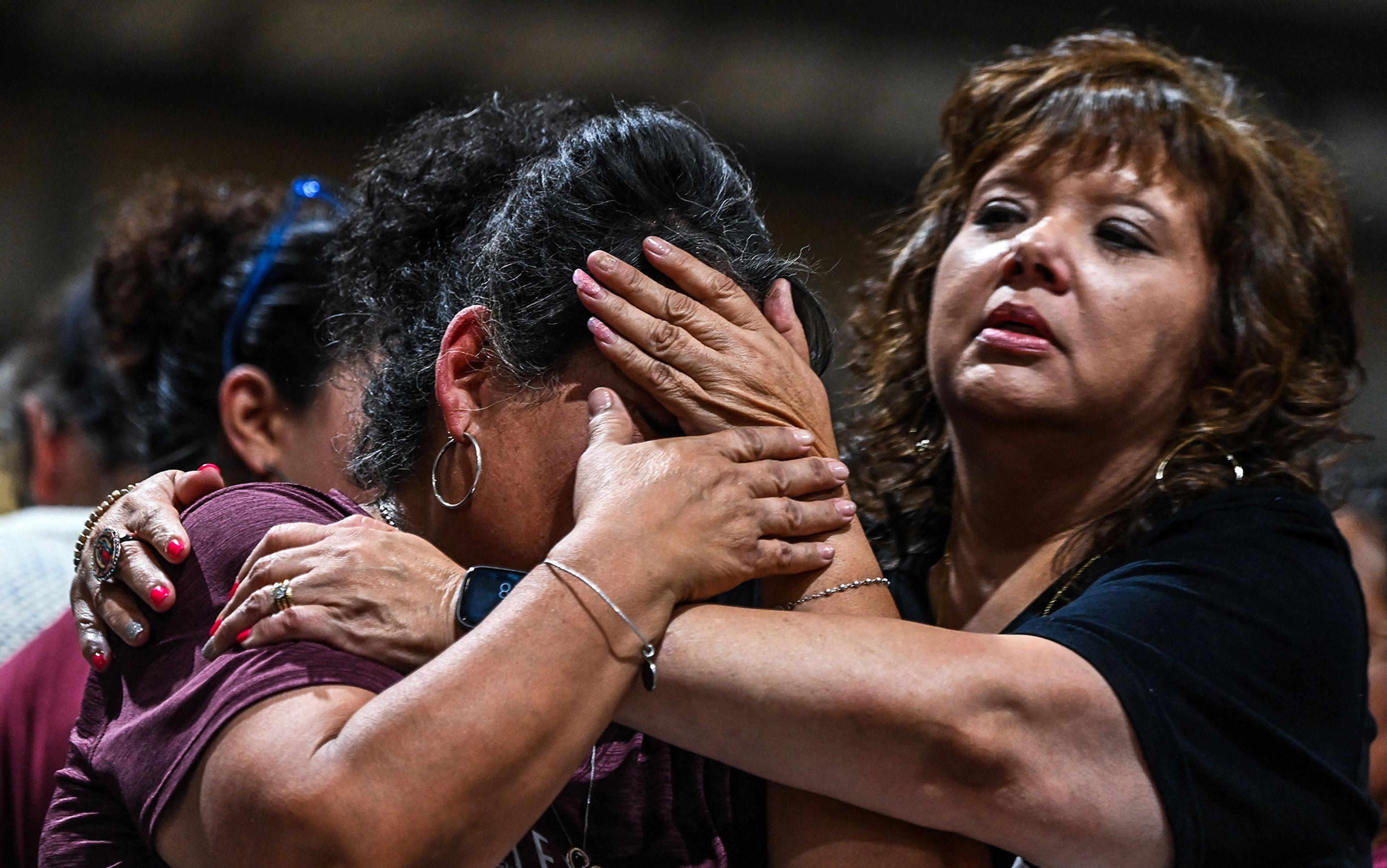

I thought about the tragically endless stream of current-day Till-Mobleys – all those Black mothers of children shot dead by the police who become, overnight, a temporary fascination, as they struggle to find words in a sea of microphones flanked by Ben Crump and Rev Al Sharpton. I wondered if, given the opportunity, these mothers would prefer to grieve privately, like me – buried under the duvet, scrolling through family videos and weeping. Is this instantaneous activist role their choice? Do they feel exploited, their private pain transformed into public spectacle? Doesn’t reliving the story of their tragedy compound their trauma? Are they weary of turning their pain into purpose? Would they rather someone ready their bed?

I am a grieving parent. I am also a scholar of social movements, so I took my grief and my questions and, instead of starting that foundation, I did what I do. Together with my students, I collected data and used it to make sense of the who, why, what, when and how of grief-induced activism. While traumatic loss is ubiquitous, our productive engagement with its consequences lags far behind. There is little systematic investigation into how trauma shapes activism, even while activist efforts flourish in diverse areas, from gun law reform and police brutality to opioid addiction, suicide and COVID-19. I agree with the writer-activist Malkia Devich-Cyril who insists: ‘To have a movement that breathes, you must build a movement with the capacity to grieve.’ If it is true that grief is love with nowhere to go, then activism provides a place for that love. Accidental activism agitates for a better, changed tomorrow.

But it is wider than that. It makes meaning and instils purpose. It knits people into communities. And it enables those living with a hole in their hearts to remain in relationship with the loved ones lost. By transforming their grief into grievance, they carve a sustainable path forward in the interminable wilderness of traumatic grief. Rather than letting go, bereaved activists are holding on, and they are challenging us all to sit with painful truths instead of running from them.

To do my research, I sought out grief- and trauma-induced activists (borrowing from the moniker that the bereaved activist Kim Witczak claims for herself, ‘the accidental advocate’) – those driven to establish charities, organise fundraisers, and/or launch awareness campaigns to address the causes of death, all in their loved ones’ names.

Jenny Stanley is among those interviewed. She lost her six-year-old daughter Sydney when she climbed in the family car – parked in the driveway – by herself. Sydney could not get back out, and no one could find her until she was dead of heatstroke. Her mother has become a national authority on the fatal dangers of hot cars.

My students and I spoke to people who, now, in the wake of their traumatic loss, became experts in hazing, partner violence, suicide, drug addiction, medical errors of various kinds, hospital-acquired infections, natural disasters, car and truck crashes, illness and pulmonary embolisms linked to hormonal birth-control use. This list – which I often recite – invariably generates head-shaking because it captures our worst fears come to life – and death. These losses are preventable and thus, impossible – for most – to rationalise. Especially for the bereaved parents, they are also a direct affront to the natural order of things, so much so that we lack a common term for bereaved parent.

When others are pressing them to let go, they use their activism to hold on

Some of those interviewed are familiar, such as Candace Lightner, founder of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD); Judy Shepard, mother of Matthew Shepard, and Susan Bro, mother of Heather Heyer (both victims of high-profile hate crimes); and Cindy Sheehan, who reignited the antiwar movement in the US in the early 2000s after her son Casey Sheehan was killed in the war in Iraq. Others are connected to events that continue to grab national attention, such as parents of children murdered in mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas in 2022; in Parkland, Florida in 2018; in Newtown, Connecticut in 2012; and in Aurora, Colorado in 2012. Others still are members of the #SayHerName Mothers Network, family of Black women and girls killed by police.

The accidental activists long for a deeper cultural recognition of loss. Through their work, they make their grief legible in a culture that turns away from their pain. As activists, they can grieve out loud. Their activism is a potent means of survival. When others are pressing them to let go, they use their activism to hold on.

The accidental activists taught me how they hold on in three interrelated ways. First, through their activism, they craft a purpose that gives shape and meaning to their lives. Second, their activism connects them with a supportive community of other bereaved people – a real lifeline. And third, as activists, they continue their role – as parent, sibling, partner – with their dead loved one.

Their lessons also point us toward a new way of thinking about grief. Grief is not a problem to be solved, but rather an emotional reality that demands acknowledgement. As the psychiatrist Judith Herman asserts in Truth and Repair (2023), trauma is a social problem, not an individual one. It requires collective and sustained acknowledgement.

While on a college service trip to a Haitian orphanage in 2010, Britney Gengel was killed in a catastrophic earthquake. Just hours before the quake hit, Britney texted her mom with her wish to someday return to Haiti and set up her own orphanage. Soon after Britney’s death, the Gengel family founded the Be Like Brit foundation, realising Britney’s vision. The orphanage is shaped in the letter B for Brit, best visible from the sky.

In our interview, Britney’s dad, Len Gengel, shared:

For me, continuing the activism has given her death meaning. Without it, it feels completely senseless, I can make no sense of it. But with it, it helps me to make some sense of a devastating and senseless death. That if her death, and her life, can in any way help other people, and it has helped thousands and continues to help thousands. It really helps me with my grief. It’s about finding purpose and meaning. And if there can be meaning made from her death, it is much easier to hold.

Like Len says, if there can be meaning, it is much easier to hold. The accidental activists are crafting purpose, searching for meaning – what David Kessler (a bereaved parent and long-time collaborator of the celebrated grief expert Elisabeth Kübler-Ross) calls the ‘sixth stage of grief’. To be clear, they are not seeking a meaning for the death of their loved one, but rather a way to transform their pain into purpose, a process that restores much-needed control for the traumatised.

As Nicole Hockley, the mother of one of the victims of the Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut explained: ‘What happened, the murder of my youngest son, was not something I could control. What happened after? That was my choice.’ Hockley, now a nationally recognised expert on school safety, chose to co-found the Sandy Hook Promise foundation to prevent school-based violence. She told me that, every morning when she rises, she kisses the urn that holds her son Dylan’s ashes. This daily act renews her purpose and enables her to live with the unrelenting pain of her son’s senseless murder.

The accidental activists expressed frustration because their trauma and grief often went unacknowledged. They complained about family gatherings, for instance, where the person missing goes unnamed. They told tales of running into old friends who breezily asked: ‘What’s new? Everything good?’ without so much as a nod to the loss they are bearing. So, what’s a bereaved person to do? In short, find others who share your experience.

Forging community means finding that ‘soft place to land’, a phrase I gratefully adopt from Sandy and Lonnie Phillips who founded Survivors Empowered after their daughter Jessica Redfield Ghawi was murdered in the 2012 mass shooting in a movie theatre in Aurora, Colorado.

In 2014, Tanisha Anderson was in the midst of what family members call ‘one of her bad days’ when her brother called 911 for mental health support. When the police arrived, she panicked and ran into the street. The police cuffed and forced her on to the pavement outside her home in Cleveland. As an officer kneeled on her back, Tanisha died of a heart attack. Her death was determined a homicide.

For bereaved activists of colour, finding community was especially important

Tanisha’s mother Cassandra Johnson was a proud member of the #SayHerName Mothers Network until her own death in 2021. Cassandra helps us understand the healing power of the network, directly challenging the assumption that being encircled by others who also suffer compounds our misery. In a video posted on the #SayHerName website, through tears, she shared:

Oddly as it may sound, to be around these mothers … makes you feel better. Most people, they might say: ‘Oh I know how you feel.’ No, you don’t!! So, to be around mothers that really do … makes you feel a lot better, as oddly as it may sound.

We collected dozens of comments like Cassandra’s. For bereaved activists of colour, once they located their purpose, finding community was especially important. Activists described how they forged new connections through activism at fundraisers, legislative strategy sessions, lobbying days, press junkets and participation in issue-oriented conferences. It was in these spaces where they felt most at home or, as one bereaved activist put it, ‘where I could actually breathe’. Activism enabled them to connect with others who ‘got it’, and these linkages enabled them to keep going.

The state of grieving is fertile ground for activism, but it needs community to sustain and grow.

The greatest fear of the bereaved is that their dead loved ones will be forgotten. To resist this slow erasure, the activists assumed the role of caretaker of their loved ones’ legacy. Some, like the Gengel family, do this by continuing their unfinished projects or realising goals that their premature deaths prohibited.

Many also work to control the narrative of their loved ones’ life and death, especially when the circumstances of the death are (unfairly) ripe for victim-blaming, such as in the case of police-involved murders or drug overdoses, especially when the victim is Black, Brown, poor, queer, mentally ill or otherwise socially marginalised. Activists will, for example, work to circulate images of their loved ones that challenge racist assumptions of ‘thugs’ and, instead, represent the deceased as respectable and productive members of the community. In some cases, surviving loved ones frame the death as a catalyst for change. As George Floyd’s young daughter Gianna shouted at a press event: ‘Daddy changed the world!’

Rae Ann Gruver travels the country speaking to fraternities and sororities about the dangers of hazing. She lost her son Max Gruver to a hazing incident in his first weeks of college at Louisiana State University in 2017. Unwavering, she exclaimed: ‘I want every member of every fraternity to know Max’s name.’ The impulse, yet again, is for the death to ‘mean something’. Through storytelling and advocacy, relational bonds are maintained.

For those left behind, there is a persistent sense of obligation, amplified for those carrying regret

Throughout this work, the activists often speak of the dead in the present tense and endow them with the capacity to guide the work of the living. For example, Lori Alhadeff lost her teen daughter Alyssa when she and 16 others were shot dead at Marjory Stoneham Douglass High School in Parkland, Florida. Lori, now a school board member and founder of the NGO Make Our Schools Safe, declares: ‘Alyssa still, you know, is here making an impact and saving lives.’ Lori believes that her daughter is actually guiding her to make change. She told me: ‘Alyssa is pulling the strings.’

What’s more, for those left behind, especially bereaved parents, there is a persistent sense of obligation, amplified for those carrying regret. As Dru West, who lost her daughter Julia West Ross to a pulmonary embolism linked to birth control, and has since become a fierce health advocate, now explained: ‘I am trying to do for others what I wish someone had done for my daughter.’ Importantly, they did not experience this responsibility as a burden, but rather as means to maintain connection and, perhaps, make amends. The bereaved activists are clear they are not ready to end the relationship with their loved ones. Fundraising for a foundation, drafting legislation (typically named after the deceased) and speaking at rallies provides a platform where they can invoke their loved one in socially acceptable ways. In this context, they can still be ‘Gracie’s mom’ or ‘Woody’s wife’.

Indeed, the bereaved activists challenge the very finality of death. But there may be downsides to accidental activism.

Sybrina Fulton, the mother of Trayvon Martin, reflecting on her highly visible activism fighting for justice for her son, offered this in the documentary Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story (2018): ‘Had the tragedy not been so public, I could have been given more time to grieve, but I was not given that privilege.’

The privilege to grieve? The notion of grief as anything but a right freely claimed and a healthy response to loss is perverse. But, in a grief-averse culture that offers little more to the grieving than sappy sympathy cards and a few weeks of casseroles delivered to their front door, activism seems an apt response.

Fulton’s experience highlights how broken are our systems of support for the bereaved. We cannot forget that these activists are forged in the horrible crucible of their traumatic losses; they are transformed overnight, and they need support and acknowledgement of their daily struggle to survive.

In 2016, Korryn Gaines, a 23-year-old hairstylist and the mother of two young children, was shot to death by Baltimore police after a nearly six-hour standoff in her home. Her five-year-old son, Kodi, was also shot but survived. Later, Korryn’s brother posted a memorial video to Twitter with the comment: ‘I miss her so much, but Im okay’ [sic]. Her mother, Rhanda Dormeus, re-Tweeted the video with the poignant rejoinder: ‘WE’RE NOT OK.’

These few words are a portal to the world of the bereaved who struggle against the culture of grief-aversion and a rush to closure. Increasingly, we pathologise grief, as seen in the latest edition of the DSM-5, known as the bible of psychiatry. It now includes a controversial new diagnosis: prolonged grief disorder.

Yet there are consequences for our chronic discomfort with grief, even while trauma, paradoxically, gains traction in an ever-widening collection of narratives surrounding us. Traumatic grief is omnipresent in film, stand-up comedy, TV series, TED talks, music and writing of all sorts. It is so ubiquitous, writes Parul Sehgal in The New Yorker in 2022, that the ‘trauma plot’ has been reduced to a trope – reductive, stereotypic and distorted.

We need to stop pushing closure as the salve that will heal the broken heart

This discomfort manifests in the rush to end grief, to ‘solve’ it. We call this ‘closure’, and it is, without a doubt, the dominant discourse of grieving. Yet the researcher of family stress and ambiguous loss Pauline Boss and the sociologist Nancy Berns both assert that chasing closure is counterproductive.

Every one of the individuals interviewed for my study categorically – emphatically – refused the goal of closure. When asked what they thought about closure, they laughed, rolled their eyes, shook their heads or threw up their hands. West, whose daughter died from a hormonal contraceptive’s side-effect, put it best: ‘Closure is for cupboards.’ Then why do people assume we want it and need it? In short, others want us to find closure; others think that grief has an expiration date because our grief makes them uncomfortable. And as Nelba Márquez-Greene said on the 10-year anniversary of her daughter Ana Grace’s murder at Sandy Hook Elementary School: ‘I walk into a room and I still make people cry.’

So what do these grieving activists tell us?

In short, we need to resist the cultural aversion to grief, and we need to stop pushing closure as the salve that will heal the broken heart. These moves are not repairs. Instead, they are invalidations of true suffering, and they block honest reckoning.

When bad things happen, we struggle with what to do, what to say. People react with pity – which is a distancing move. Or with sympathy, which also puts space between us. In an RSA short video in 2010, the renowned speaker and author Brené Brown says: ‘Empathy fuels connection. Sympathy drives disconnection.’ Rarely, if ever, does an empathetic response begin with ‘at least’. ‘Silverlining it’ (Brown’s tongue-in-cheek term) does not help. And neither does putting our grief in a box on a shelf.

Grief is powerful, necessary and enduring. When we embrace grief in our social movements, we inch closer to accountability and justice. Devich-Cyril’s question hits the mark: ‘What becomes possible when movements are brought more healthfully to grief, and what can we do to support leaders, organisations and movements to get there?’

For bereaved people of colour, the need is especially urgent. Let’s be real. For those lacking privilege, (not too) angry shouts capture attention, but quiet tears do not. Racism erases some stories of trauma, often rationalised by victim-blaming; at the same time it renders stories of Black and Brown death as sources of prurient entertainment. As Rhaisa Kameela Williams explains in ‘Towards a Theorization of Black Maternal Grief as Analytic’ (2016), historically speaking, Black maternal grief has been rendered illegible until it is transformed into the more culturally acceptable form of grievance. However, what bereaved families and friends – of all races – want is accountability. Banded together with others who experienced similar traumatic losses, they are emboldened to fight for the justice owed.

At the same time, I will not forget the bereaved brother who advised against founding ‘another fucking foundation’. Is activism in fact a road that should be less travelled? Can we build an emotionally literate and more community-minded world where the bereaved are held and heard without having to do extraordinary things?

Márquez-Greene’s exasperated Tweet really underlines this question. After the massacre in Uvalde, Texas, she wrote: ‘One of the biggest mistakes made in covering the uniquely United Statesian epidemic of gun violence in media is the demand for a tragedy-to-triumph narrative because the reality is too hard.’

So, what needs to change in the wake of tragedy? Frustratingly, I offer no clear prescriptions other than this: meet the grieving where they are at, especially when that place makes you uncomfortable and even fearful. And when you encounter accidental activists, remember that, even though they are carrying the grief, it does not mean it’s not heavy. Offer to help. Show up. Contribute. Learn, and pass on the lessons.

What about me? I hesitate to call myself an accidental activist, certainly in comparison with the people I’ve met through my work. While we have made some modest efforts to raise awareness about distracted driving, our work honouring Gracie has focused on what brought her joy in her life – figure-skating and art. We set up a scholarship for skaters for a few years, and we have funded a youth public-art project – a set of middle- and high-school student-designed beautiful banners that line our main street every spring since 2016. Each banner includes the line: ‘Made possible by the family of Gracie James’, and when I see that, my feelings are complicated: pride, deep sorrow, longing and wonder: what would my forever 17-year-old daughter think of this visibility? And then I tell myself: if it helps me – in some small way – to stay connected to my girl, to ‘do something’ in her name, and to remind the people in my community that there was a beautiful girl who mattered, someone who counted, then that eases my suffering just a bit. But my ambivalence troubles me. Should we fund this project indefinitely? No matter what we do, Gracie is forever gone. Am I seeking comfort in the wrong place?

But I should not have to translate my grief into grievance or public art or skating scholarships to be heard and seen. I was profoundly altered after her birth, and then even more profoundly after her death. Who is willing to witness my pain – without expectation or judgment or, worse, shrinking away?

Who will see and hear yours?

After all, grief is coming for us all.