‘Far away, where the swallows take refuge in winter, lived a King who had 11 sons and one daughter, Elise. The 11 brothers — they were all princes — used to go to school with stars on their breasts and swords at their sides. They wrote upon golden slates with diamond pencils, and could read just as well without a book as with one, so there was no mistake about their being real princes. Their sister Elise sat upon a little footstool of looking glass, and she had a picture book which had cost the half of a kingdom. Oh, these children were very happy, but it was not to last thus forever.’

So begins ‘The Wild Swans’, my favourite fairytale when I was a girl. I must have read it a thousand times. Because Elise is a princess, the young reader can safely infer that everything is going to work out fine — even though her wicked stepmother opens the proceedings with a bang, by turning her brothers into 11 beautiful wild swans. (‘They flew out of the palace window with a weird scream,’ and no wonder.)

The story appeared in a green cloth-bound edition of Andersen’s Fairy Tales, along with the brick-red companion volume of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, each boasting a lovely gilt-ornamented pastedown picture on the front cover. The Hans Christian Andersen volume contains the particularly beautiful and eerie illustrations of Arthur Szyk. It was the first slipcovered set I ever owned — glorious possessions, I thought then, as now.

These books are chockablock with stories of royals. In the case of Princess Elise, a typical specimen, her countless virtues — goodness, beauty, piety, etc — are corollaries of her royal blood. This intrinsic, absolute, inborn excellence enables her to defeat evil, because goodness is more powerful than evil. Take, for example, the poisoned toads that her terrible stepmother sneaks into the princess’s bath. Toads! So awesomely creepy! But instead of bewitching the princess into becoming ugly and cruel, as planned, they turn into scarlet poppies the moment they touch her royal bod, because it is too pure and good to be poisoned.

All this is by way of saying that in the United States we haven’t got any actual royals, and yet almost the very first stories we hear are about princes and princesses, kings and queens. When a little American kid first learns that there is such a thing as real, live princes and princesses, who live in actual palaces, this is liable to come as a terrific shock, though in general a pleasing one. One would like it to be true; it’s a very nice idea, that there is such a thing as an incorruptible person for whom everything will — everything must — come right in the end.

There are only 30 monarchs left on Earth, according to the oracle at Wikipedia — 29 if you don’t count Pope Francis. The Middle Eastern potentates, Elizabeth II and a few defanged Europeans, a smattering of Asians and Africans, and the king of Tonga; that’s about it. Not one of them evinces all that much in the way of nobility, genius, bravery, courtesy or tender concern for his people, so far as I can make out. But how could it be otherwise? Even the best of them have to ply their trade in a world of terrible complexities and compromises, rather than in the world of wicked stepmothers.

In the West, the monarchy is no longer large and in charge, it can’t have anyone thrown in a dungeon, it can’t send armadas around to wreak havoc. All we’ve got is a grouchy little old lady whose hats are probably the scariest thing about her, and a decent-seeming Spanish guy with a busted hip and a corrupt son-in-law. The real institution was pithed, hollowed out long ago, and a sea of sweet, gentle fairytale associations has swept into the place where it used to be.

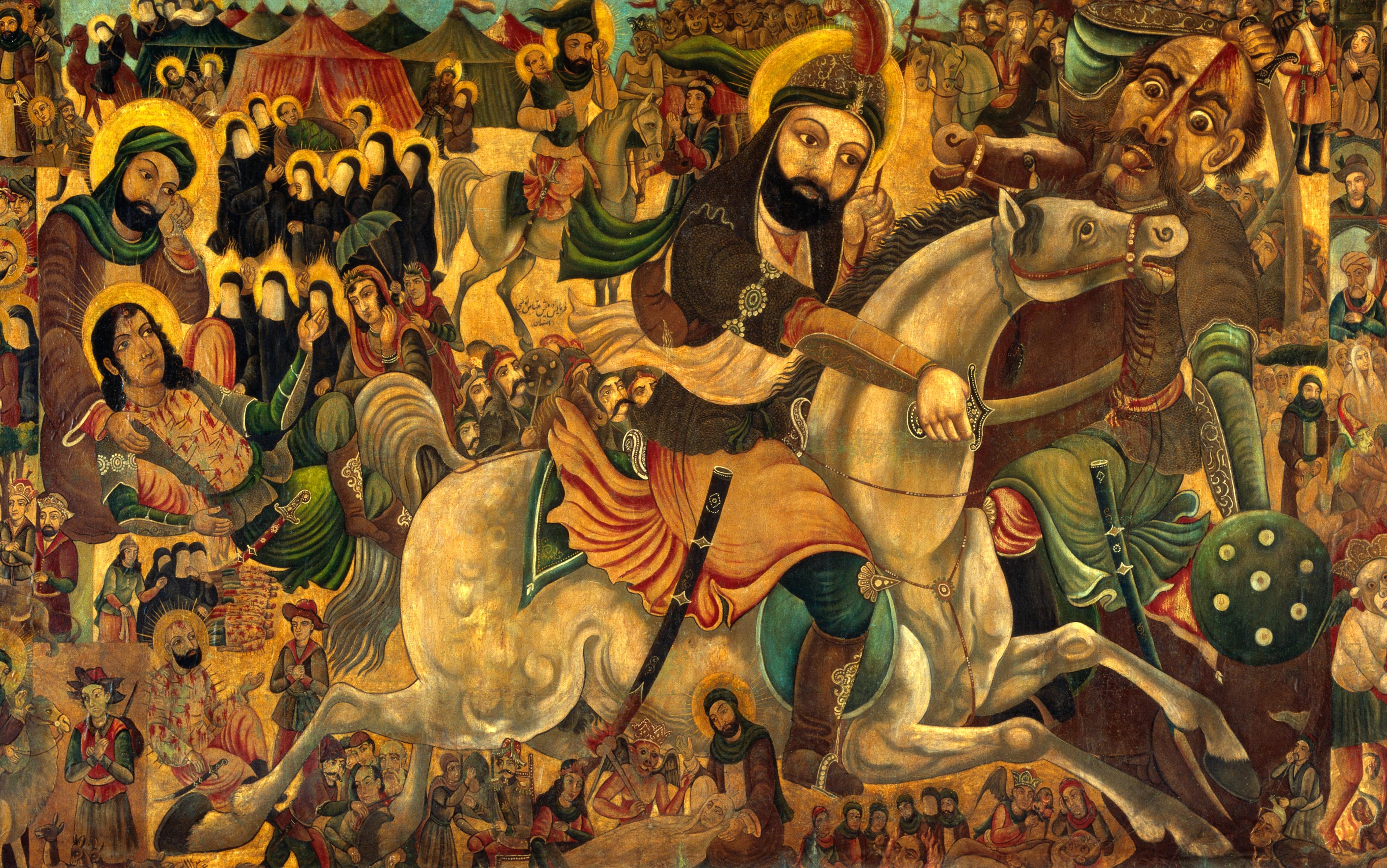

In this way, the atavistic love and wonder for the institution of monarchy never quite fades from American hearts. The attachment that begins with fairytales is reinforced by the more complicated chivalric ideal deeply rooted in the stories of King Arthur, Lancelot, Sir Gawain and their literary successors, the works of J R R Tolkien: all peculiarly English dreams of the search for a just ruler. Dreams, too, of manly restraint, power and stoicism, womanly modesty and gentleness, of perfect manners, beauty and grace: the elevation of the noblest human qualities, and the banishment of all that is gross and corruptible in us.

The actual royals appear to Americans more or less like reality TV stars — not quite real, but not at all ideal, either

It’s worth noting that in America, no crass reality need ever disturb these pleasant fantasies. Though ‘Kate & Wills’ might be featured on the cover of Us Weekly magazine (‘Doing It Her Way! How Baby Changed Kate’), they resemble neither real people nor fairytale ones, appearing as they do alongside the plasticised figures of ‘Kim & Kanye’s TV Wedding’, ‘Lisa’s Wild Attack (“Brandi Is ‘Disgusting’”)’ and ‘Hot Photos! Set Secrets! From the New Film, Catching Fire’. The actual royals appear to Americans more or less like reality TV stars — not quite real, but not at all ideal, either.

The chivalric code might have originated in medieval France, but the bloody curtailment of that nation’s royalty prevents Americans from idealising the French monarchy in quite the way we do the English one. We love the Scarlet Pimpernel and do not care for Madame Defarge. Perhaps it is not too much to say that monarchy means, in the American mind, the English ideal of monarchy — by which I mean the literary, Arthurian vision of monarchy, rather than the vaguely Prussian variant that has sat stiffly upon the real-life English throne since the Hanoverian succession.

Quasi-Arthurian tropes have long found their way into our most beloved cultural institutions. In Star Wars, the Jedi Knight Anakin Skywalker is secretly married to a princess; their son, Luke Skywalker, has both royal blood and the best sword-arm in the galaxy. Consider the complex aristocracy of Frank Herbert’s Dune saga, the rough nobility of the Klingon aristocratic ‘houses’ in Star Trek, the princess-packed narratives of a TV series such as Adventure Time or a franchise such as My Little Pony. Though our confused notion of monarchy might be full of dreams and mirages, it’s also a real and highly monetisable commodity, as the burgeoning fortunes of the Walt Disney Company, those arch-purveyors of princess gear and ersatz castles (NYSE: DIS $68.12 -0.88 (-1.28%), at time of writing), have demonstrated all my life — and my kids’ lives, too.

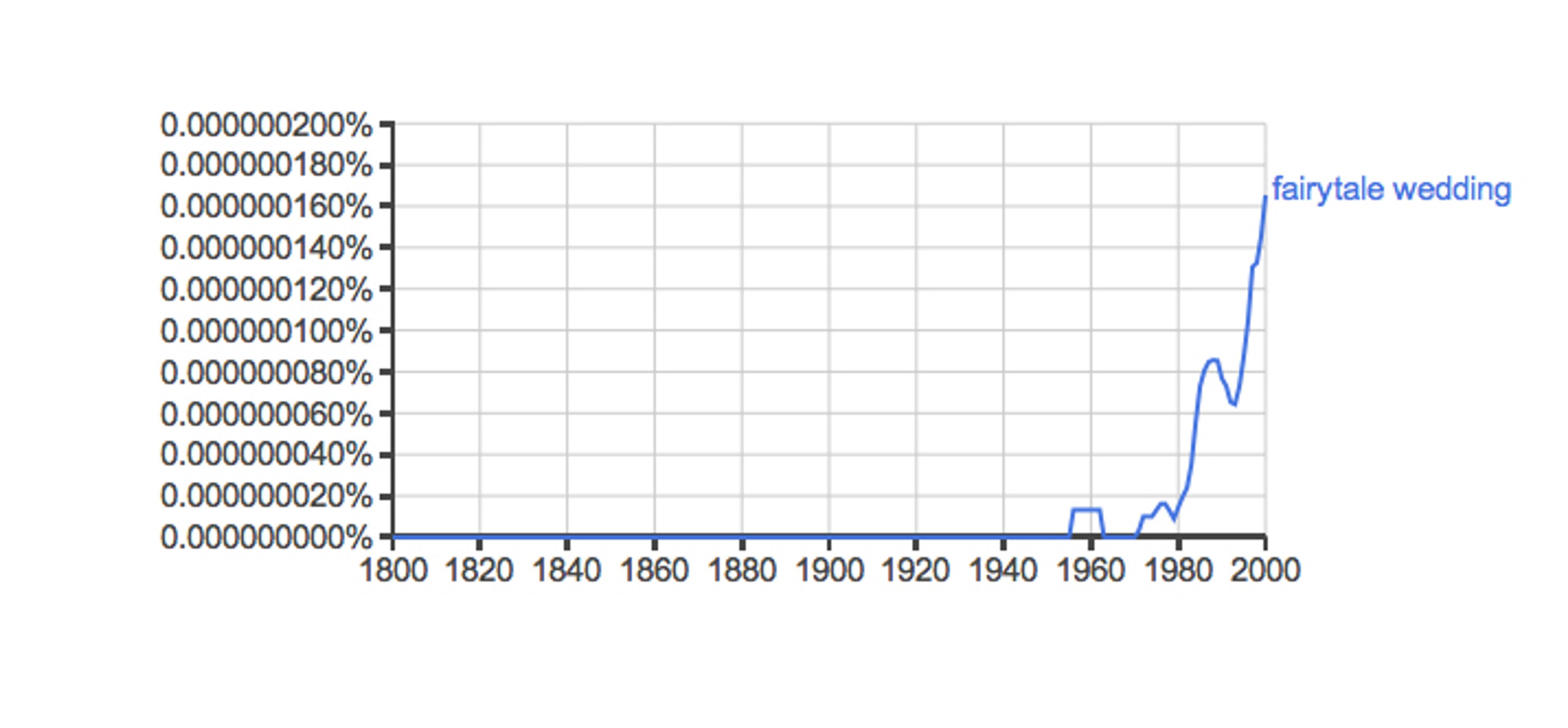

Then again, there’s a deep symbiosis between our fantasies of monarchy and the ‘real’ monarchy of the United Kingdom that has long ensured that the latter, too, remains a monetisable commodity. So it was that in 1981, with the full force of every fairytale and Disney princess behind it, the vision of the Royal Wedding was sold to a world eager to believe. What happened next might have been a stone-cold bummer but, make no mistake, we still like the idea of a ‘fairytale wedding’.

Ngram-Fairytale

My husband is English, with roots in Manchester and the Isle of Man, and though his politics have veered increasingly to the left in recent years, he is still an Englishman through and through – in truth a romantic, like his dad and brothers. He won’t quite stand up with a glass of sherry before dinner and solemnly intone ‘the Queen’, but almost. So, for many years there has been lively disagreement around here on the topic of the Windsor family, and particularly Elizabeth II, whom my husband likes for her humour, devotion to duty, and matter-of-factness, and whom I do not care for, since I really am a dyed-in-the-wool Madisonian antimonarchist and democrat who thinks it totally immoral for one person to own a Vermeer.

Maybe nobody could live in that kind of a fishbowl and maintain his sanity, but the tabloid antics of the Windsors seem just ridiculous, hilarious even, until one considers that the citizens of the UK have been made to foot the bill for these people to live in unimaginable luxury, for which largesse they have been repaid with a never-ending spigot of boring rich-people high jinks. Many of those who lived through the ‘fairytale wedding’ of Charles and Diana came to feel they’d been sold a very sad bill of goods.

My husband counters this argument with the usual ones about how the royals are a focal point for national solidarity, good for tourism and so on. The fact is, though, that he just likes them, in the Ray Davies manner: ‘God save little shops, china cups and virginity’ (difficult as it is to believe that the lead singer of the Kinks ever did much for the cause of virginity). What my husband and Mr Davies share, I believe, is a kind of nostalgia for the royalist myths of their own youth, whose origins are very different from the fantastical, fairytale ones. A kind of conservatism.

an American visiting the UK is apt to feel a strange nostalgia; a sadness, like a faint pain in a phantom limb

American anglophiles come in various types (literary, rock and roll, Masterpiece Theatre, sword ’n’ sorcery) but they, too, share a little of that conservative impulse — literally conservative, I mean, as in the kind where you ‘conserve’ things. I’ve never met anyone raised in the US who didn’t go at least mildly gaga over the countless venerable and beautiful monuments, churches, parks, castles, universities, public buildings and works of art in the UK. Certainly I’ve felt that all my life. So little that is distinctively American has been preserved, and so much has been lost, even in our far shorter history, that an American visiting the UK is apt to feel a strange nostalgia; a sadness, like a faint pain in a phantom limb, for our failure to preserve the best elements of our own culture for the pleasure and improvement of future generations, as the British have so admirably done.

America loves heroes, and the Arthurian heroism that reverberates through our culture is eternally pure, without stain. It’s a true thing, however fantastic in its origins, made of our real desire for a world better than the one we have.

English friends have often asked me about this, as one did recently: ‘Why don’t Americans despise the very idea of monarchy? I thought that was the point of America!’ This strikes me as a wonderful mirror of our feelings about England. Just as our English friends very reasonably hope for more from us with respect to the ideal of democracy (and how good it would be, if we would comply!) so do we hope for more from them, perhaps, than ever can be instantiated in the real world, with respect to the ideal of kings and queens, princes and princesses. As if we were calling to one another across the sea: O distant cousins whose music and stories I vastly admire! For god’s sake, be better than us! We can’t be blamed for wishing, just a little, that the real royalty could bear at least a trace of Gawain or Aragorn, just as our English friends might wish that we Yanks could contain at least a small tincture of James Madison or Thomas Paine.

We live through poor kings and presidents, I guess, and preserve our institutions as best we can, in hopes that our descendants will be better and wiser than we, and in hopes of better tenants of those institutions in times to come. So I might not be too willing to hoist the sherry myself, but I shan’t complain if anyone else wants to.