A 42-year-old single friend tells me she is thinking of freezing her eggs. I nod with a tight, fake smile. I’m torn: on the one hand, I know how tough everything to do with fertility is because my husband and I have been trying to have a baby since we got married three and a half years ago when I was 41 and he was 45. On the other hand, going through this, and writing about it for The New York Times Motherlode blog, I’ve amassed a vast trove of information about in vitro fertilisation (IVF), egg-freezing and women’s fertility. I know you can’t start thinking about freezing your eggs at 42. Because even if you immediately stop thinking about it and start doing it, it probably wouldn’t work at that age.

What I really want to tell my friend is that if she is serious about having a baby, her best bet would be to go out to the nearest bar and hook up with a stranger – during her 36-hour ovulation window, of course. But I won’t tell her to sleep with a random guy, I won’t ask if she ovulates regularly, nor will I say anything else about the state of her ticking – nearly stopped – biological clock: it’s too delicate a subject.

Besides, I know exactly how she feels. I know how little we women know about our own fertility – despite the daily bombardment of news about declining fertility and egg-freezing and snatching up a husband in college à la the notorious ‘Princeton mom’, Susan Patton, author of Marry Smart (2014), who says women at Ivy League universities should spend that time to find a mate. After all, I didn’t know much about fertility either.

It was three months before my 41st birthday when I went first went to a gynaecologist to discuss what steps to take before trying to conceive. Solomon and I had been dating 15 months and had just had the ‘talk’, a vague discussion in which we concluded that I would go off birth control and we’d start trying to get pregnant. (It would take me another three months and a ring to understand that the baby talk was his proposal for marriage.) I found a female ob/gyn, whom I believed would be more sensitive than a man.

‘So, I read somewhere that you shouldn’t start trying to conceive until you’ve been off birth control for a while,’ I said to the gynaecologist. ‘How long should I be off the Pill before I start?’

‘Well, I wouldn’t wait if I were you. You don’t have much time,’ she said snidely.

Ouch. I looked up from my note pad, where I’d been scribbling notes from our conversation, like ‘get a mammogram’ and ‘start taking pre-natal vitamins’. I’d been in the woman’s office for about 10 minutes and it felt like she was being… well, kind of a bitch.

‘Excuse me?’ I said. I felt like I’d gone to buy lipstick at a cosmetics counter and been offered plastic surgery.

‘You’re almost 41. You don’t have time to wait,’ she said again with a grim look in her eyes. I still wanted to know whether trying to conceive immediately after stopping the Pill could raise the chance of birth defects. (I later learned that that’s patently false – a woman’s fertility is often higher right after she goes off birth control.) But her comment was said with such finality, such disdain – and no actual medical facts to accompany it – that I just took my mammogram script and high-tailed it out of there.

I didn’t heed her advice. I suppose I was still fixated on the ‘first comes love, then comes marriage, then comes baby in a carriage’ thing – and I waited half a year until the month of my wedding to have unprotected sex. Lo and behold, a week or two after the nuptials, I discovered I was pregnant. Huzzah! I wanted to throw the positive pregnancy test in that smug gynaecologist’s face and say: ‘Who you callin’ old now, girl?’

But before I could make it to a doctor (a different one), I miscarried. Then I got pregnant again, then miscarried again. Over the next three and a half years, I moved from natural conception to assisted reproduction and IVF, and subsequently learned everything I never wanted to know about pregnancy, miscarriage, age and fertility. Alas, it was too late for me. Sure, I’d gained all this knowledge about the speed of fertility decline but, at 43, I was getting too old to have a baby.

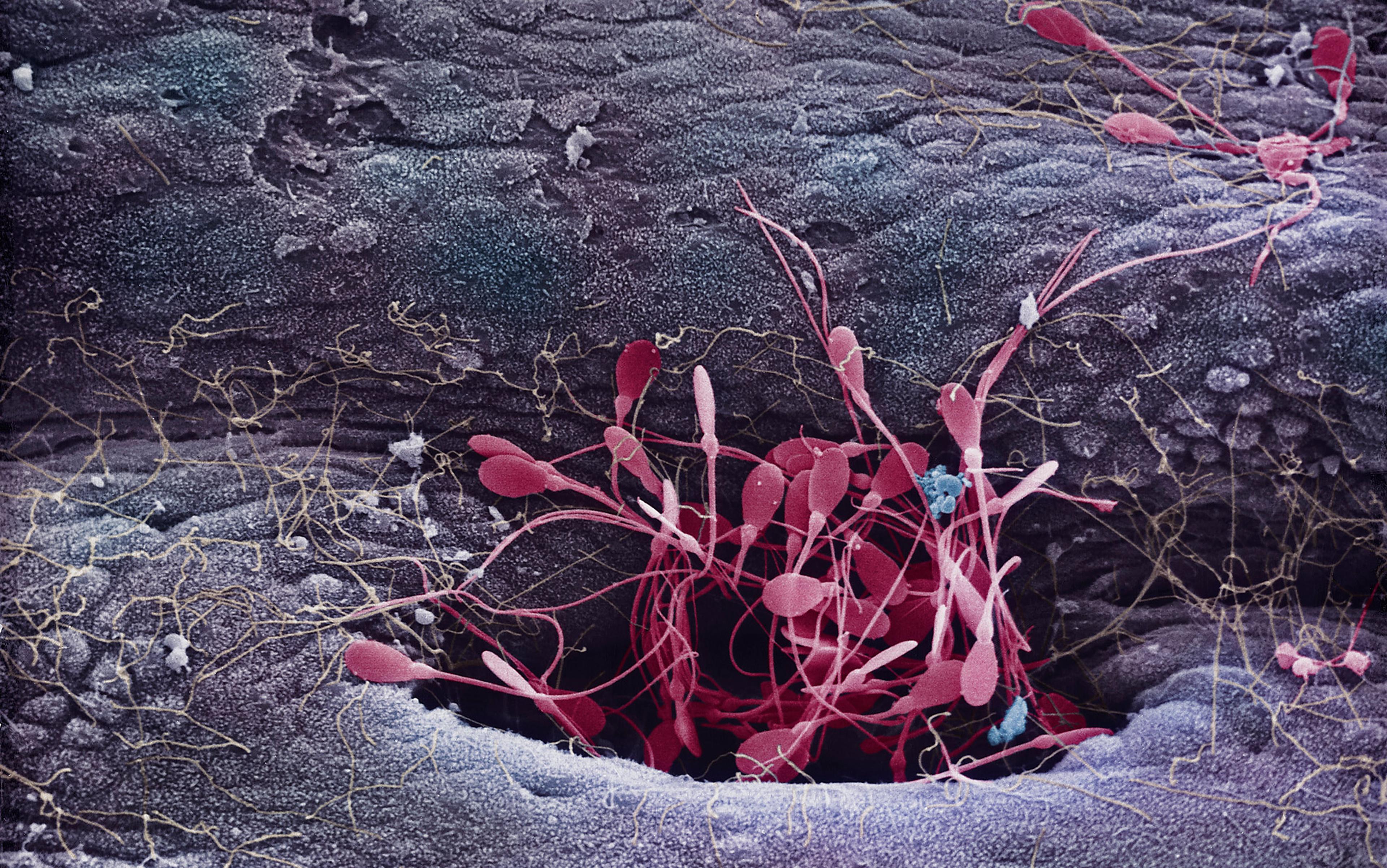

It’s too painful to wonder what would have happened if that first gynaecologist had sat me down calmly and opened up some informative graphics to show how women’s fertility drastically declines with age – beginning at around 32, more rapidly after 37, then precipitously at 40. The way a doctor might explain to you the risk of smoking by showing you a picture of blackened lungs, or describe the effects fat has on arteries, often leading to heart attacks: simple medical facts, presented in an objective manner, without judgment or guilt or some hidden cultural agenda.

Sadly, all this is missing from the discussion on women’s fertility.

Many studies show that women are not only woefully ignorant when it comes to fertility, conception and the efficacy of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) – but they overestimate their knowledge about the subject. For instance, a 2011 study in Fertility and Sterility surveyed 3,345 childless women in Canada between the ages of 20 and 50; despite the fact that the women initially assessed their own fertility knowledge as high, the researchers found only half of them answered six of the 16 questions correctly. 72.9 per cent of women thought that: ‘For women over 30, overall health and fitness level is a better indicator of fertility than age.’ (False.) And 90.9 per cent felt that: ‘Prior to menopause, assisted reproductive technologies (such as IVF) can help most women to have a baby using their own eggs.’ (Also false.) Many falsely believed that by not smoking and not being obese they could improve their fertility, rather than the fact that those factors simply negatively affect fertility.

‘You don’t have much time,’ she said snidely. I felt like I’d gone to buy lipstick at a cosmetics counter and been offered plastic surgery

Fertility fog infects cultures and nations worldwide, even those that place more of a premium on reproduction than we do in the West. A global study published for World Fertility Awareness Month in 2006 surveyed 17,500 people (most of childbearing age) from 10 countries in Europe, Africa, the Middle East and South America, revealing very poor knowledge about fertility and the biology of reproduction. Take Israel, a country that puts such a premium on children that they offer free IVF to citizens up to age 45 for their first two children. According to a 2011 study in Human Reproduction, which surveyed 410 undergraduate students, most overestimated a women’s chances of spontaneous pregnancy in all age groups, but particularly after receiving IVF beyond age 40. Only 11 per cent of the students knew that genetic motherhood is unlikely to be achieved from the mid-40s onward, unless using oocytes or egg cells frozen in advance. ‘This can be explained by technological “hype” and favourable media coverage of very late pregnancies,’ the authors concluded.

Media hype is one reason why so many overestimate the possibility of getting pregnant when older. With frequent news stories of older celebrities having babies – Amanda Peet (now expecting her third child at 42), Jane Seymour (who had twins at 44), Geena Davis (twins at 48), Kelly Preston (third child at 48), Beverly D’Angelo (twins at 49) – it’s hard not to think the sky’s the limit.

But the stories behind how these actresses came to have these children hardly ever come to light: for example, was it their first child? (A woman who already has children is more likely than a first-time mother to conceive when older.) Did she use IVF? (Most celebrities do not admit it.) Most importantly, did she use her own eggs or donor eggs? (Donor eggs from younger women reset the fertility clock, because it’s the age of the egg, not the uterus, which matters most – up until age 45, when age begins affecting pregnancy even with donor eggs.)

The stories behind how these actresses had their children at such advanced age hardly ever come to light. Yet fixation on celebrity fairy tales gives the rest of us false hope

For a woman over 42, there’s only a 3.9 per cent chance that a live birth will result from an IVF cycle using her own, fresh eggs, according to the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). A woman over 44 has just a 1.8 per cent chance of a live birth under the same scenario, according to the US National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Women using fresh donor eggs have about a 56.6 per cent chance of success per round for all ages.

Indeed, according to research from the Fertility Authority in New York, 51 per cent of women aged between 35 and 40 wait a year or more before consulting a specialist, in hopes of conceiving naturally first. ‘It’s ironic, considering that the wait of two years will coincide with diminished fertility,’ the group says.

Stories of celebrities and other older women having babies have led to misunderstanding precisely because they fly in the face of long-held beliefs: for many years, all women heard was that fertility takes a dive at 30-35. But when you see plenty of people having no trouble having babies until 40, you think it’s just a scare tactic. That’s what happened to me, anyway. Raised in a traditional Jewish, family-oriented community that emphasises early marriage and plenty of children, I was constantly warned about waiting too long to get married and have kids. But when I left that community, I saw so many women who had kids at 37, 38, that I thought it was all bubbe meises, old wives’ tales.

It’s not. There is a declining rate of fertility strongly tied to age – but the exact numbers have recently come up for debate. In a piece for The Atlantic in 2013 headlined ‘How Long Can you Wait to Have a Baby’, the psychologist Jean Twenge showed that much of the research cited by articles and studies (such as how one in three women aged 35-39 will not be pregnant after a year of trying) was based on ancient figures, such as French birth records from 1670 to 1830. She also cites a 2004 Obstetrics and Gynecology study examining chances of pregnancy among 782 European women. With sex at least twice a week, the study found, 82 per cent of 35-to-39-year-old women conceived within a year, compared with 86 per cent of 27-to-34-year-olds. ‘In our data, we’re not seeing huge drops until age 40,’ Anne Steiner, an associate professor at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, told Twenge.

This information might have helped people such as me. Had I known that 40 was the real age when fertility generally takes a dive – and not that I’d long passed it five or 10 years’ prior – I might have rushed into baby-making. I might have saved myself from a hellacious IVF journey that still hasn’t ended.

It’s easy to blame our cultural fertility fog on the media and faulty scare-mongering statistics. But the problems go way deeper – and start much earlier.

‘I think as a society no one tells women what fertility is,’ said the reproductive endocrinologist Janelle Luk, medical director of Neway Fertility in New York City. When it comes to women’s health, she said: ‘There’s a cultural barrier.’ Even a menstrual period is only discussed in terms of inconvenience, cramps and pain. ‘When you’re 15 or 17, you’re not planning to have a family, and you only learn about preventing pregnancy,’ she added.

‘Women don’t know there’s a limit: the message is equal, equal, equal. But our biological clock is not’

Luk became interested in women’s health issues from an early age. Her own mother had been given away in China as a baby and raised by relatives because she was a girl. They moved to the US when Luk was 10, and by the time she was in college she got involved as a sex health advocate. She talked on campus about sexually transmitted diseases such as the human papilloma virus (HPV) and chlamydia, which causes infertility in 10 per cent of the infected. ‘It’s part of biology, and women should know because the consequences are severe: HPV could lead to cervical cancer – it’s not fair, but that’s how it is.’

‘No one talks about fertility,’ said Luk, who does not believe women are really open to hearing about it. ‘I don’t think women know that there’s a limit: the message is equal, equal, equal. Women say: “We want to go to college, we want to work on our careers, we want to be equal to men.” But our biological clock is not.’

Or was not, she adds. Today, especially in the past two years, with the advancements in egg-freezing – the flash-freezing vitrification process improves egg survival rates to 85 per cent – women can start to level the playing field by freezing their biological clocks. The problem with oocyte cryopreservation? ‘The younger the better,’ Luk told me – before the age of 30 is ideal. But women often don’t become cognisant of the need to do it until their fertility starts declining, and the process is less likely to produce a baby.

Another way women might even out the fertility playing field is by focussing on the so-called male biological clock. But is there one? Although there have been recent news stories about how advanced age in men (over 40 or 50) increases time to conception and the incidence of autism and schizophrenia, the absolute risk is negligible. ‘When you look at the numbers, you have to separate what the absolute risk and the increased risk is,’ said Natan Bar-Chama, director of male reproductive medicine and surgery at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. ‘The absolute risk is still really very small.’

Fertility fog is not just a cultural problem, it’s human nature, says Aimee Eyvazzadeh, a San Francisco Bay Area fertility specialist who calls herself the egg whisperer. Recently, a 51-year-old woman telephoned her to discuss egg-freezing. ‘Nobody wants to be told they’re infertile. Women are shocked when nature applies to them,’ she says. She wishes women were more informed. She recommends a woman start by talking to her mother.

Women can also take certain tests to ascertain their fertility age. One blood test measures follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), indicating the egg quality, especially as compared with other women in the same age group. Another test, for Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), assesses ovarian reserve (how many eggs are left) and their potential for fertilisation. ‘It’s part of general health to prevent infertility,’ Eyvazzadeh said. Patients in their 40s complain to her that they wished they’d gotten those blood tests earlier, because now they can’t use their own eggs. ‘If she were counselled at an earlier age, and educated, perhaps she would have made different decisions.’

But who is going to counsel women who are so in the dark? In 2014, The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) had its Committee on Gynecologic Practice deliberate the issue. The Committee Opinion recommends education about age and fertility for ‘the patient who desires pregnancy’ – and that is a quote.

there are no guidelines for talking to a woman about her fertility unless she herself brings it up

In other words, only women who are already trying to get pregnant or thinking about it should be counselled about how age affects fertility. But what about the other women – the ones who do not realise their fabulous health might not protect them from age-related declining fertility; the ones who might want to start thinking about freezing their eggs while they’re still young enough; the ones who are waiting for one reason or another to have a baby and don’t know that perhaps, like me, they don’t have that much time. Does ACOG believe it’s the doctor’s responsibility to bring up the subject?

‘We feel that women should be able to talk to their ob/gyn about fertility,’ said Sandra Carson, ACOG’s vice president for education. ‘We certainly want to remind women gently that, as they get older, fertility is compromised, but we don’t want to do it in such a way that they feel that it might interfere with their career plans or make them nervous about losing their fertility.’ In other words, there are no guidelines for talking to a woman about her fertility unless she herself brings it up.

All this talk of ‘gentle’ reminders and ‘appropriate’ counselling has a history – a political one. Back in 2001, the ASRM devoted a six-figure sum to a fertility awareness campaign, whose goal was to show the effects of age, obesity, smoking and sexually transmitted diseases on fertility. Surprisingly, the US National Organization for Women (NOW) came out against it. ‘Certainly women are well aware of the so-called biological clock. And I don’t think that we need any more pressure to have kids,’ said Kim Gandy, then president of NOW. In a 2002 op-ed in USA Today, she wrote that NOW ‘commended’ doctors for ‘attempting’ to educate women about their health, but thought they were going about it the wrong way by making women feel ‘anxious about their bodies and guilty about their choices’.

Although the ASRM denies the backlash is connected, its spokesman Sean Tipton says the organisation has not done a fertility awareness campaign since.

In the end, lack of fertility education on the medical side and the unwillingness to explore it on the patient side seems to come down to the fear of offending women.

Naomi R Cahn, author of Test Tube Families (2009), argues that ‘the politics of reproductive technology are deeply intertwined with the politics of reproduction’ but ‘although the reproductive rights issue has a long feminist genealogy, infertility does not’. Discussion of infertility is threatening to feminists on two levels, she contends: ‘First, it reinforces the importance of motherhood in women’s lives, and second, the spectre of infertility reinforces the difficulty of women’s “having it all”.’

the debate over egg‑freezing involves such work-life concerns as better maternity leave and family rights

Even a debate over egg-freezing has assumed political overtones. When Facebook and Google recently announced that they would pay $20,000 health benefits for female employees who wanted to freeze their eggs, ‘Room for Debate’ roundtable discussion in The New York Times had three of the five women opposing it: one was worried about the health concerns, another about fairness, and the third about corporations paying women to delay motherhood. In other words, the debate over egg‑freezing involves such work-life concerns as: ‘Why don’t we have better maternity leave?’ or ‘Why isn’t this country more supportive of family rights?’

I was one of those arguing in favour of egg-freezing, because despite success rates being low, they are better than waiting five years with older eggs. At 35, you have 20‑30 per cent chance of your frozen eggs creating a baby in the future, using IVF. At 42, it is 3.9 per cent – the difference is vast.

Unfortunately, the polarising nature of the debate on egg-freezing does little to lead us out of our fertility fog or illuminate the discussion. It just has many women categorically deciding they’re not going to freeze their eggs. That is a perfectly acceptable choice, except that these women seem to be deciding without investigating their individual fertility status, relinquishing control over their fate.

‘Shunning that information about the relationship between fertility and age, however, ignores biological facts and, ultimately, does a disservice to women both in terms of approaching their own fertility and in providing the legal structure necessary to provide meaning to reproductive choice,’ writes Cahn.

Although published five years ago, her words are particularly prescient in the US today in light of proliferating anti-abortion laws and ‘personhood legislation’ – proposals to declare legal human life from the minute an egg is fertilised, granting an embryo the same rights as a newborn. Resolve, the national US infertility awareness movement, resolutely opposes personhood legislation because it ‘would produce so many legal uncertainties about the status of embryos’ that it would make IVF virtually impossible. In the US, IVF would go the way of abortion, with clinics closing their doors, especially in conservative states; women would have as much difficulty getting fertility treatment as they do abortions.

Maybe this threat to embryos and IVF will finally wake women from their fertility fog and allow them to be educated about their own bodies, its capabilities and its limitations. Just like they would be informed about any other medical condition.

‘It is only with this information that reproductive choice becomes a meaningful concept,’ Cahn writes. ‘Choice cannot mean only legal control over the means not to have a baby, but must include legal control over the means to have a baby.’