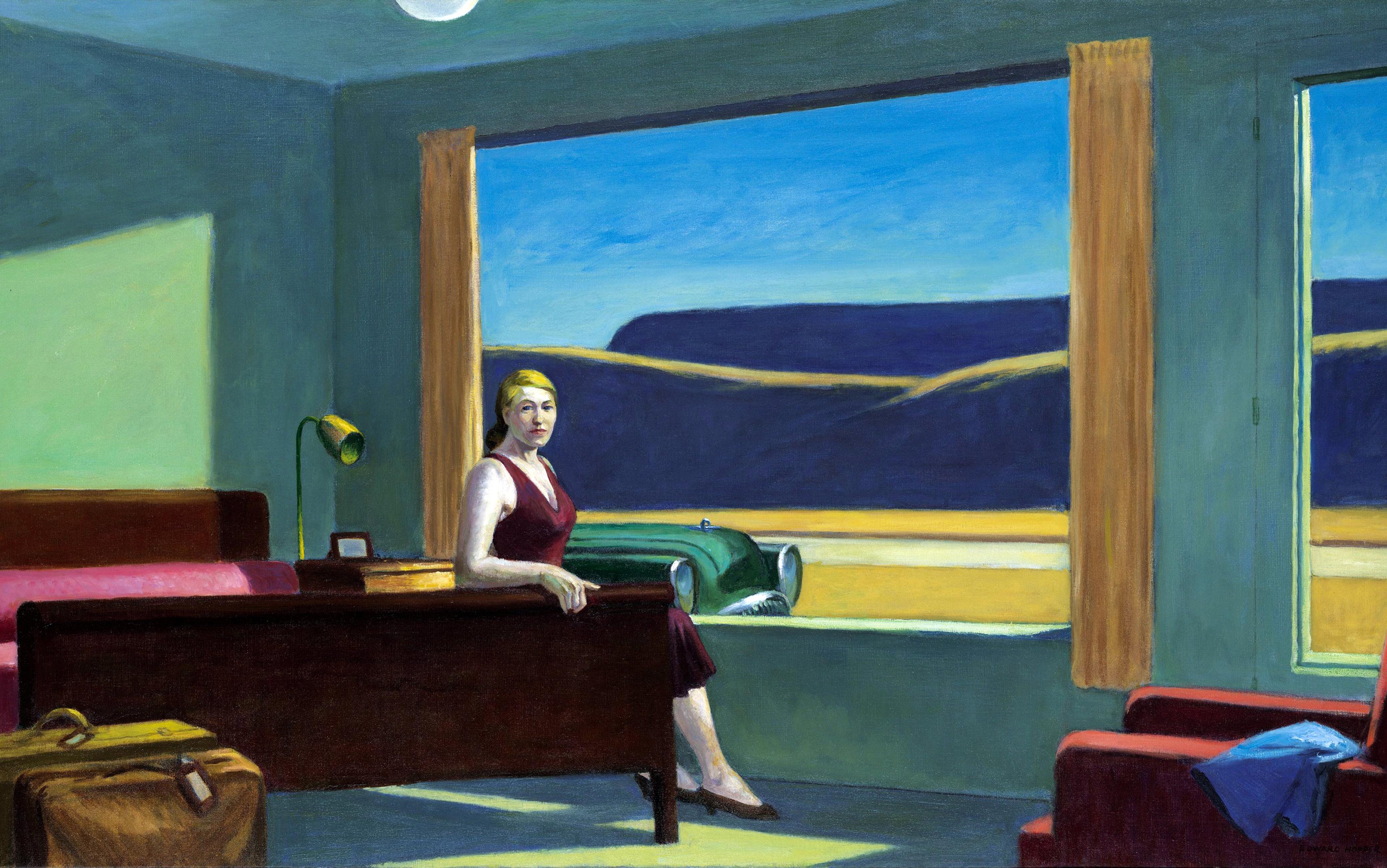

There was a period in my life when I spent a lot of time in hotel rooms. It was normal to skit from Shanghai to Dublin via Vilnius and Rome in a month, and then begin the loop all over again: Athens, Novosibirsk, Kuala Lumpur. I travelled alone to these cities and when I got there I was required to stand on stages, sit on panels and talk endlessly. At the end of each jet-lagged and scrambled day, I would go back to my hotel room where sometimes the mini-bar was stocked, sometimes not. The aircon would rattle, or not work, or be set too high or low with a fixed dial, and I would attempt to relax on an oversized bed with stiff pillows, listening to the TV from next door or to strangers whispering in the corridor.

I lived in a hotel in Moscow called the Cricket for a month. In European countries, I stayed in compact three-star rooms, while in the Middle East it was always big chains: the Sheraton, the Radisson or the Hilton Nile. Here and there, depending on local deals and the nature of my stay, I’d take a room in one of the iconic, colonial-style hotels from the novels of Graham Greene or Agatha Christie: the American Colony in Jerusalem, the Pera Palace in Istanbul or the Taj Mahal Palace in Mumbai. I travelled like this from my mid-20s for a decade. Sometimes I was single, other times in a relationship, and the eternal transience suited me at the start. It was fun, for a few years, until suddenly it wasn’t.

On arrival, I liked to wash away long journeys with a swim in the hotel pool, usually found in the bowels of the building. I would trek along corridors in fluffy hotel slippers, past rows of identical doors, almost naked under the bathrobe, both intimate and exposed. The pool would invariably be empty, and as soon as I took my glasses off I could no longer see the edges of the fake palm trees or the steps to the Jacuzzi.

For a long time, the swimming ritual was helpful. I would cleanse away London-me and become a shiny new, international person. But then in one pool, after a particularly disorientating 18-hour journey, I floated on my back, buoyed by chemicals and water, and heard an odd bright voice in my head offering up a simple suggestion. I want to die, it said. A calm, sane voice, perfectly integrated with the flickering light reflections on tiles and the sound of lapping water, of drips from the sauna room, of taps being turned on somewhere else in the building. I flipped onto my stomach and began a slow breaststroke. Go down, it said, and so I did, swimming underwater with eyes closed until I nudged the edge of the pool just as I imagine a shark might nose against the side of a boat.

The next time it happened, the voice was stronger, and the time after that, stronger again. An insistent, reasonable interior monologue. Where am I? Random swimming pool, random country. Whom do I know here? Nobody, really. Who would miss me? Nobody, really. Go down then, into the chlorine-blue, and let go, said an unambiguous and rational voice that terrified me.

A person is not supposed to be in both Asia and Africa in the same week on a regular basis; the world should not be traversed at that speed. It was scrambling, discombobulating; worse, it was damaging – some central element of my subjective self was being ebbed away. Yet, I still said yes. I was the go-to girl for a last-minute flight to anywhere, and whenever I returned home, lightly tethered to a house-share in Brixton, south London, I plotted to be away again.

When I climbed out of a taxi on my way home, or dragged my suitcase towards my front door, I would think of Jean Rhys, writing in Good Morning, Midnight (1939): ‘Walking back in the night. Back to the hotel. Always the same hotel … You go up the stairs. Always the same stairs, always the same room.’ My life on a loop, searching for the new, but in reality going round in circles.

the mirrors, doors, locks, balconies and bathrooms of hotel rooms became active props and surroundings for the process of ‘going to the other side’

There is a part of the brain called the hippocampus that is shaped just like a seahorse. It is in many ways still an unconquered mystery, but it is believed to act as an internal sat-nav. It provides a crossroads between memory and the processing of location, and not just locations of geography and place – although it does deal in those, contextualising landmark objects and images to understand landscapes, interiors and scenes – but also the mapping of an emotional geography such as future goals and aspirations and how to reach them, or memory sequences, or the systemisation of our own personal narratives. It is how we understand where we are and how we put ourselves into the points of view of others. Depression has been found to have a dampening and distorting effect on the hippocampus, so that we become, in many layers of the word, lost.

I don’t know if my hippocampus navigator was suppressed by too much travel or if I was simply exhausted from a decade of avoiding intimate relationships and any semblance of a stable home. Whatever it was, the suicidal impulse triggered by the architecture of hotels and all the signifiers connected to them – key cards, long corridors, the ting of a service bell – kept growing stronger.

I had been restless for 10 years, swinging between a ‘home’ that consisted of a transient rented room and the never-ending process of arriving alone at an Italo Calvino-esque city of everywhere/nowhere. I was lonely, getting lonelier, and ebbing across to the other side of the mirror with no idea how to stop it happening.

In my final year of intensive travelling, I developed insomnia so acute that the only way I could cope was to read all night and catch up on sleep during the siesta, if I was in a siesta-friendly country, or cat-nap in the late afternoon hours where I was often free before getting ready for evening activities.

During these difficult nights when the alien city outside my window often seemed paradoxically too empty and too full of people, I found myself reading about the Surrealists and their relationship with cities, travel, escape, and hotel rooms. In Katherine Conley’s book Automatic Woman (1996), I read how the German artist Unica Zürn (the partner of fellow artist Hans Bellmer) was interned into a psychiatric asylum in the 1960s as a result of smashing a windowpane in a hotel room in Berlin. André Breton’s muse ‘Nadja’ was also incarcerated due to her ‘erratic and odd behaviour’ in a Paris hotel, and the British-born artist and writer Leonora Carrington, with whose work I had become fascinated, was arrested and detained in a clinic as a result of stripping naked and confronting staff of the Hotel Ritz in Madrid.

That all three women came undone, psychologically speaking, in hotel rooms is not a surprise. They lived peripatetic, transient lives anyway and, for these women associated with Surrealism, the mirrors, doors, locks, balconies and bathrooms of hotel rooms became active props and surroundings for the process of ‘going to the other side’, much encouraged and exploited by the male artists in their lives. The Surrealists were obsessed with encounters with the unconscious, with dalliances with madness and most often it was the women who were pushed – or chose to jump – all the way into the rabbit hole while their male counterparts looked on. It was through doorways opened by women that male Surrealists felt they could reach a pure state of psychic automatism – in other words, art outside the confines of reason, or moral or aesthetic control – and the hotel room was often the perfect theatre for these experiments.

Zürn deliberately placed herself in anonymous rooms to allow the hallucinations to occur

Zürn in particular was a full-bodied manifestation of the paradoxical other, occupying an entirely liminal space. She would walk a few paces behind Bellmer, not simply a muse but also a living embodiment of the life-sized, pre-pubescent dolls he made. Zürn suffered three breakdowns, each precipitated when she went away from the apartment in Paris she shared with Bellmer, or away from her children from a previous marriage, and installed herself in a hotel.

In her autobiographical writings, Zürn wrote that a hotel room became ‘a huge empty stage, almost dark, [it] appeared, not like the product of a hallucination, but more like a clear picture that forms in the centre of one’s being…’ The trigger, she wrote, was looking through the hotel window and experiencing hallucinations relating to a childhood trauma: her family home was auctioned when she was 15, along with all its contents. It signalled the destruction and loss of her family as she knew it, of her childhood, and a fundamental part of herself.

Zürn was attracted to madness and embraced it, deliberately placing herself in anonymous rooms in order to allow the hallucinations to occur. She traversed borders between reality and unreality, exemplified by images relating to rooms and houses. She wrote:

This house, bathed in an emerald green light, becomes transparent. Through the walls she can see. The inside: she sees the Indian Buddha from the Temple of the Rocks, the big Chinese dragon embroidered in gold and silver thread on a black velvet background, the Arab lamp with golden, red, and green light. But this image of the interior of the house is brief, the walls close up again … The door closes again, and the entire house, even the green fairy light under which the house first appeared, melts away.

A few years later, in 1970, having suffered another cycle of hallucinations followed by a crashing return to reality, she committed suicide by throwing herself from a balcony in Paris.

I have a collection of hotel-headed notepaper and I use it to write people notes, instead of sending postcards. The American poet Elizabeth Bishop, an inveterate traveller for the duration of her life and no stranger to hotels, drew sketches on hotel stationery. One such drawing is her room at what was the Murray Hill Hotel in New York, and the space she captures feels claustrophobic, confined. In the story ‘In Prison’ (1938) she writes: ‘The hotel existence I now lead might be compared in many respects to prison life, I believe: there are the corridors, the cellular rooms, the large, unrelated group of people with different purposes in being there that animate every one of them but it still displays great differences.’

The hotel experience boils down to the room: the confinement of the space that is at once personally yours and not yours, cell-like, an entrapment. Jonathan Ellis writes in Art and Memory in the Work of Elizabeth Bishop (2006) that ‘wallpapered rooms were always difficult spaces for Bishop to settle down in because of their link to childhood fears’. Just like Unica Zürn looked out of hotel windows and saw the demolition of her family home, it finally occurred to me that it makes no difference how far you run – to a hotel perched on the edge of the universe perhaps – the room one takes will always be wallpapered with childhood fears and in the bathroom half-light you will always look like a ghost.

I moved back to the seagulls and the shabby hotels, to work on making an uneasy peace with standing still

My sense of dis-ease grew when travelling, so I tried to bring things from home to make me feel grounded. But I quickly realised that I did not own anything other than books that had any personal meaning, and this fact alone made me sad and question the way I had been living my life. I began to feel panic whenever I was around the furniture and fittings of international hotels: the purposefully generic lobby, the vast reception desk. It got so even the dining spaces and stairwells of hotels began to induce anxiety when I walked through them.

A sense of entrapment, claustrophobia and paranoia but, above all, the acute feeling of being lost: where am I? Where the hell am I? The blood and muscle and bone of my body continually whirred in failed attempts to locate myself – perhaps the hippocampus seahorse in my brain was doing somersaults – and, as a result, a permanent, shameful feeling of drowning. I had to stop travelling, I decided; stay at home for a while. I gave up the international job and decided to sit still and write.

The closest I could get to staying at home was to take up a writer residency in a hotel in Margate, Kent, where I intended to shut myself up and finish a piece of work. I thought that remaining in the UK would keep me on safer, dryer ground. No hotel swimming pools, no more loss of self through the cracks of fractured time zones or hallucinatory jet-lagged evenings.

In my damp little room overlooking the grey sea and a bleak promenade, I began to draw a map, a constellation of writers and artists I felt were somehow inheritors of the earlier Surrealist’s endeavours; queens of the night in nameless hotel rooms. From Leonora Carrington to Jean Rhys. From Jean Rhys to Amy Winehouse. From Amy Winehouse to Tracey Emin, Margate’s greatest export, whose childhood home was the Hotel International in Margate, a seafront hotel run by her father. It was a place of no safety for the young Emin as is well documented through her art career.

One of Emin’s pieces, entitled ‘Hotel International’ (1993), is a quilt made of hand-stitched felt words, using fabrics and materials from her life. In an interview with Carl Freedman in 2005, discussing her use of homely spaces, re-making dolls houses, using quilted materials, blankets and tents, she was asked: ‘Do you feel like a little girl, playing with furniture, when you create these homes?’ She answered: ‘Possibly.’ ‘So you are trapped in the past? You are involved in yourself to the degree that you can’t move away from it?’ ‘Maybe I am trying to put home right,’ she replied.

I grew up in a clapped-out seaside town on the south coast of England, not so many miles away from Emin’s Margate. I did everything I could to escape the shingle, the bad weather, the faded, John Betjeman‑esque hotels where I had summer jobs waitressing for sleazy hotel bosses, serving ice cream to ancient old ladies. For many years, I equated this chalky, desolate coastline and the squawking of seagulls with death: the end of the world, the end of time.

I circled the globe as many times as possible, but just as Jean Rhys found herself continually back in the same bedsits – ‘predestined, she had returned to her starting-point in this little Bloomsbury bedroom that was so exactly like the little Bloomsbury bedrooms she had left nearly 10 years before…’ – I find myself living again in a similarly run-down seaside town, a spitting distance from London, a spitting distance from Gatwick airport, walking along a tide-line scattered with cuttlefish bones and dried fish eggs. I now live close to a seafront lined with shabby hotels with names such as the Belle View and the Sea Bright. When I peer into the windows, I think of Elizabeth Bishop’s disparaging list of hotel ‘decorations’: the ‘unattractive wallpaper’ and the ‘Turkey carpets’. In the end, to remain alive, I gave up the fancy travelling job. I gave up pretending that London, or any other city, was my home and moved back to the weather and the seagulls and the shabby hotels, to work on making an uneasy peace with standing still.

When I think about that time of my life now, a spiralling-down that surprised me and which I barely survived, it is entirely connected with the hieroglyphs of hotels. I ask myself Bishop’s famous line: ‘Should we have stayed at home, wherever that may be?’ My answer is that I don’t think so. I don’t regret all the running away but I do understand the risks of travel a little better.

I have a few rules now: don’t go for too long, always come back, make sure to remain tethered by animals, children, houses and husbands, anything that can be clung on to and turned into an anchor. When I recall the swimming pools in those grand hotels, and all the associated symbolism – the unconscious, the enclosed and confining aspects – I imagine myself lying on my back in the water, allowing myself to be carried, floating, and I am no longer afraid of the sensation of being weightless. It is less like drowning, or falling, but simply being taken along.