Driving on one of New York’s poorly maintained and crowded roads, I found myself in a situation one can more safely observe through numerous YouTube ‘bad driver’ videos: a driver for whom all other traffic apparently ceased to exist confidently pulled into a lane I already happened to occupy. After a quick manoeuvre that probably spared me a role in one of the aforementioned videos, I said, perhaps louder than was necessary, to nobody in particular: ‘Is this [deleted] aware of anything but his own [deleted]?’

Because I am a philosopher, and thus tend to be rather bad at letting go of ideas – especially ideas without good answers – my close brush with YouTube fame led me to consider other instances of what has come to be called ‘main character syndrome’ (MCS) or, perhaps more annoyingly, ‘main character energy’. Not a clinical diagnosis but more a way of locating oneself in relation to others, and popularised by a number of social media platforms, MCS is a tendency to view one’s life as a story in which one stars in the central role, with everyone else a side character at best. Only the star’s perspectives, desires, loves, hatreds and opinions matter, while those of others in supporting roles are relegated to the periphery of awareness. Main characters act while everyone else reacts. Main characters demand attention and the rest of us had better obey.

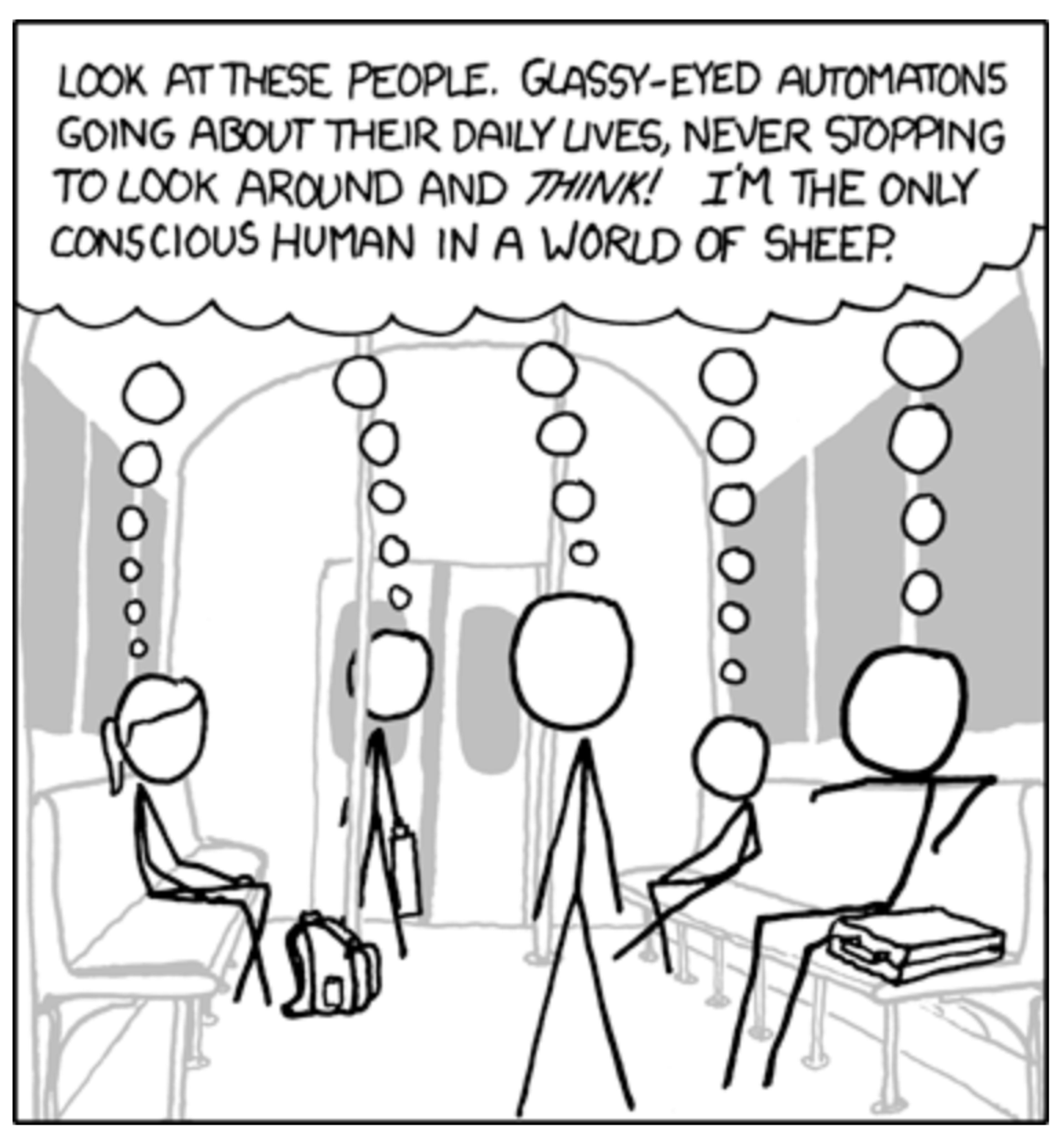

You have probably heard of MC behaviour – or perhaps even witnessed it online or in person. A TikToker and her followers physically push aside those inconvenient extras ‘ruining’ their selfies – and then post their grievances on social media. A man on a crowded subway watches a loud sports broadcast without headphones while ignoring other commuters’ requests to turn it down a bit. This is no mere rudeness: in the narrowly circumscribed world of main characters, the rest of us are merely the insignificant ghosts who happen to intrude on their spaces. Akin to chess pieces, or perhaps to animatronic figures, we have agency only in the development of the MC’s story. In current parlance, we are non-player characters (or NPCs) – a term that originated in traditional tabletop games to describe characters not controlled by a player but rather by the ‘dungeon master’. In video games, NPCs are characters with a predetermined (or algorithmically determined) set of behaviours controlled by the computer. Rather than agents with a will and intent, NPCs are there to help the MC in his quest, to intersect with the MC in preset ways, or to simply remain silent – a kind of prop, or perhaps human-shaped furniture, a part of the scenery. Another way to view NPCs is to imagine what the philosopher David Chalmers calls a philosophical zombie, or p-zombie, a being that, while physically identical to a normal human being, does not have conscious experience. If a p-zombie laughs, it’s not because it finds anything funny – its behaviour is purely imitative of the real (main character!) individual. For someone convinced of their MC identity, the rest of us are, perhaps, just so many zombies.

Courtesy xkcd.com

While Chalmers’s p-zombie is a part of a philosophical hypothetical concerned with the nature of mind and consciousness, the non-philosophical take on people as NPCs is deeply morally worrying. Having taught and written for a number of years in the areas of ethics and moral psychology, one of the central ideas that I have tried to explain and make more vivid is that morality is something that we do together, that our ideas about who we are require each other’s engaged participation, and that an empathetic openness not only to each other’s moral agency, but to each other’s emotional states, is central to our shared lifeworld. We must see others as fully human, and be engaged with each other as moral beings to understand who we are, and who we are in relation to others and to the world.

But the main character narrative denies all these possibilities. It is destructive to views of human beings as fundamentally relational and interdependent, and poses a threat to two important experiences of being human: the first is connection to others; the second is love.

To counter objections that my worries are a simple case of generational misalignment – a confused Gen Xer misunderstanding Gen Z perspectives – I suggest that MCS is dangerous precisely because it seems to be no passing fad, and is not limited to any one generation’s political perspective, or social group – indeed, its influence extends far beyond TikTok, and is found within the business world, in academia and in the halls of power.

As a philosopher and a narrativist, I am an unabashed supporter of the view that selves are something that we create together, through shared stories. What is a narrative? In short, anything that can be read, spoken, heard, written, viewed or otherwise expressed – and this certainly includes social media. In telling stories, we create and reveal who we think we are; in listening to the stories of others, we help to mould and sustain them as persons. Stories are thus foundational to how we view the world and our place in it, and through them we can make ourselves morally intelligible to ourselves and to others.

And this is also where we run into a problem. Setting aside critiques within philosophy itself of a narrative view of morality as epistemically unreliable and without any foundational principles, there are also worries that bear more directly on our current topic: if social media is a kind of narrative, can narrativists, such as myself, defend it on the same grounds as other narrative ways of understanding ourselves and the world? And if the answer is ‘yes’, then why am I spending all this time worrying about main character syndrome and its many stories?

The answer has something to do with the kinds of stories MCS offers. On the one hand, narrative approaches to morality and identity centre both speaking and hearing – sharing and uptake – emphasising the importance of multivocality, of shared discourse, of mutual intelligibility. They point toward the moral significance not just of one’s own stories, but of the narratives of others as guides to understanding the fundamental interdependence of human identities.

On the other hand, narratives spun by the main character have little interest in, or patience for, the stories of others; they are anything but interdependent. They care nothing for mutual intelligibility. Only the main character, his perspective, his story and his solitary self, matter. In this version of narrative selfhood, there is room only for the singular speaker, and his singularly important chronicle. Yet, as narrativists will often note, not all narratives are good, or desirable, or to be encouraged.

In fact, as the feminist philosopher and bioethicist Hilde Lindemann argues, some narratives can create spaces of moral damage that are detrimental to the identities of both the speaker and his audience, and destructive to the possibility of a shared moral universe. I suggest that narratives emerging out of the MCS phenomenon are precisely of this damaging kind.

MCS offers the wrong kinds of stories: harmful, isolating, solipsistic, amoral. And it begins, in large part, with the assumed superiority of the main character’s self-conception. While main characters are singularly important beings in their own minds, this importance comes in many flavours. Let’s begin with the usual culprit – entertainment and social media – where they can be often found in their native environment. The ‘main character’ hashtag has been viewed, mostly approvingly, millions of times on TikTok and on Instagram, and #maincharacter accompanies tens of thousands of posts. Daily, social media denizens are sold the idea that becoming the heroes of their lives is the only thing that matters.

We demand from others, both directly and indirectly: ‘Stop everything, and watch me!’

But it is not just social media: so many of our films – especially those targeting younger viewers – focus on the central quest of the hero, who must overcome, outsmart, outrun, outperform and, in the end, glory in her victory. This hero’s journey, this monomyth, is on full display in The Hunger Games movies (2012-23), the Divergent film series (2014-16), the Spider-Man universe (2018-24), and The Maze Runner films (2014-18), which are but a handful of relatively recent examples. There are sidekicks and other characters, to be sure – but, in the end, to quote the much older film Highlander (1986), ‘there can be only one’.

Absorbing these messages and mimicking the voiceovers of lead characters in films and other media, we also try to narrate our lives – often, directly into our smart phones – and share with the world all the ways in which our paths, our storylines, our perspectives, are the ones that matter, the ones worth paying attention to; our voices the voices that are worth hearing. We demand from others, both directly and indirectly: ‘Stop everything, and watch me – the hero!’

But isn’t it a bit too easy to blame media for our growing obsession with our own importance? Long before the internet, let alone social media, people have shared their narratives in diaries, autobiographies, poems and so on, bringing their lives to centre stage. Generations of Americans have been taught to pursue happiness – individual, personal happiness – above all else. There have always been solipsists, narcissists, sociopaths and simple attention-seekers – social media did not invent the me-first typology.

And yet, can we help ourselves in this time of global access to others, and to ourselves? Can we – well, some of us, anyway – resist demanding an audience when one is always there, ready to be engaged? Perhaps not. As the clinical psychologist Michael G Wetter said in a Newsweek interview in 2021, main character syndrome is:

the inevitable consequence of the natural human desire to be recognized and validated merging with the rapidly evolving technology that allows for immediate and widespread self-promotion … Those who exhibit characteristics consistent with the experience of main character syndrome tend to want to create a narrative that is dependent on an audience to validate their story. What good is a story or movie if there is no audience?

Media, social and otherwise, has made it easier, cheaper and, importantly, more socially acceptable to act out our MC monomyths. We can upload photos, videos, entire films about ourselves – and we can choose how we are perceived through clever tricks of light and angles, apps and filters that tell exactly the stories we want told. All this because we want to get noticed, we want to be seen – and seen as someone who matters, as the main someone who matters. As the influencer Ashley Ward noted on TikTok in 2020:

You have to start romanticising your life. You have to start thinking of yourself as the main character because, if you don’t, life will continue to pass you by, and all the little things that make it so beautiful will continue to go unnoticed.

Not being seen, not being noticed as someone who matters means relegating oneself to NPC-dom – a nobody, a nothing, a mannequin without a personal story or agency, going through a prewritten script of a grey, insignificant life. To be seen, on the other hand, is to be happy. This happiness requires making sure that others know that one is happy, successful, better than those NPCs – in other words, it calls for constant curation of one’s image, one’s narrative, one’s self. If one is not the MC, someone else surely will be. This is, for many, simply an intolerable fate.

Of course, blaming all media, or only social media, for MCS would be inaccurate. Perhaps unsurprisingly, main characters have emerged in places where psychopathy and narcissism have always reigned: in politics, academia and other public-facing institutions. From a US president who claims that ‘I alone can fix’ the nation’s many crises, to news and manipulative media personalities who insist that they and only they are telling the truth, to politicians who cannot – or do not wish to – tell the difference between being famous and being effective, MCS is becoming the norm.

There are worse offenders still. As an academic, I would be remiss if I did not include those within academia, or those solipsistic enough to call themselves ‘social leaders’ or, even worse, ‘thought leaders’. Specifically, main character energy seems to be especially strong among a subgroup of academics, and the philanthropists who fund them, who like to call themselves ‘longtermists’ or ‘effective altruists’.

Moved to action in significant part by the philosopher Peter Singer’s essay ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’ (1972), which argues that we are morally obligated to maximise our impact by focusing on causes that bring about the greatest quality-of-life improvements, effective altruists claim that all of us have a moral responsibility to do good in the most effective way possible – in other words, we must provide the greatest benefit to the greatest number of people that we can, regardless of where they might be located.

The longtermists consider themselves to be justified in manipulating us so that we do the right thing

Longtermism takes this utilitarian ethos many steps further, arguing that its goal is to lessen the threat of ‘existential risks’ to humanity: climate change, nuclear war, destructive asteroids and other catastrophes from space, the revenge effects of AI, and so on; longtermists extend this responsibility to future people as humanity’s major ethical priority.

One of the leaders of the movement, the moral philosopher William MacAskill, argues precisely this in his book What We Owe the Future: A Million-Year View (2022), and is echoed by the researchers in the now-defunct Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) at the University of Oxford, founded by another longtermist philosopher, Nick Bostrom. The message is generally this: we might recognise the tragedy of rationing scarce resources to the current population. However, if doing so means improving the chance of both survival and wellbeing of future generations – of which there will be innumerably more than today – then not doing so constitutes a moral crime.

So, what is the problem – and how do these academic do-gooders, and their financial backers, fit the MCS criteria? The answer lies in two necessary assumptions that effective altruists and longtermists have to make. First, because of the utilitarian calculus that underwrites both worldviews, the possibility of a vastly larger human population in the future seems to justify the NPC-ification of any humans alive at the moment. Indeed, they tell us, our suffering might be the only thing to save the future! Second, since the wellbeing of the (much smaller) current generations matters so relatively little, the longtermists consider themselves to be justified in manipulating us so that we do the right thing. Choose the right professions, contribute to the right causes, suffer the right deprivations, and so on. Because such manipulation is permitted – in fact, morally required – the agency and inherent value of Earth’s current inhabitants is not merely ignored but discounted as a morally relevant consideration. And on top of the whole scheme stands the main character whose monomyth not only grants them the moral perception to understand what really matters, but (ostensibly) the means to bring their vision to fruition, all the NPCs be damned. There can be only one, indeed.

But mattering to each other still matters. The epigraph in E M Forster’s novel Howards End (1910) is ‘Only connect!’ In an emerging modern world seemingly bent on destroying whatever humanity and interconnectedness remains, we are urged to connect the disparate parts of our own psyches and, most importantly, to connect with each other. Yet, we seem to be adrift in a world that is becoming a stage upon which increasing numbers of us choose to strut, preen, and not only declare our need to be seen and admired, but also insist that others subordinate themselves to our personas.

We have reasons to despair – but haven’t we always had them? The social media revolution, with its vast reach and siren songs of the hero’s journey or else with its cruder versions that overtly demand constant attention, is merely the current incarnation of a longstanding preoccupation with the self, with one’s identity, with one’s importance. But this is our time, our moment, and it seems that it is fitting that we respond in the best way we know how. So, while I do not pretend to have the answer – perhaps not even an answer – to addressing the moral harms of the MCS phenomenon, I do think that we can begin by asking what we are losing, and why there are reasons to try to salvage it.

I take self-creating narratives to be fundamental to who we are – by telling and hearing stories about ourselves, about others and about the world, we come to understand who, why and how we might be. Yet the kind of main-character storytelling that is presently ascendant does very little to form mutually constructed identities and, instead, reduces the complexity of human relationships to simplistic binaries of ‘me’ and ‘not me’, ‘them’ and ‘us’, ‘hero’ and ‘villain’. Instead of co-creators and co-authors of each other’s selves, what remains is an anxiety-producing, shallow, consumerist competition for the ring of the one true self, the one true main character. We thus become rivals, competitors and players in what looks like a zero-sum game of winners and losers. As the possibility of interdependently created identities disappears, we feel more alone, unheard, unseen – perhaps un-personed.

The MCS narratives lack what psychologists and philosophers call a ‘theory of mind’ – the idea that we experience other people as having the same kind of mental states that we do, rather than playing bit parts in the monomyth of our lives. This lack of an attunement to others as moral persons equal to oneself bears a family resemblance to narcissism. This sense of ‘family resemblance’, an idea put forth by Ludwig Wittgenstein, argues that various practices and ideas can be connected by a series of overlapping similarities.

Motivated by a desire to be adored, their very practices strain the possibilities of love

The family resemblance between MCS and narcissism lies in what the philosopher Aleksandar Fatic in 2023 called a kind of ‘moral incompetence’ – ‘the incompetence to experience the moral emotions, such as empathy, solidarity, loyalty, or love’. MCS and narcissism connect in their rejection of our interdependence: not only do they mock meaningful connections with others, but they make such mockery into a virtue. Because moral incompetence inhibits connection, MCS, and its close cousin, narcissism, are suggestive of the moral failure against which Forster’s epigraph warned.

But there is that other word: love. Albert Camus, in his Notebooks (1935-42), confesses that:

If I had to write a book on morality, it would have a hundred pages and ninety-nine would be blank. On the last page I should write: ‘I recognize only one duty, and that is to love.’

More recently, the philosopher Harry Frankfurt, in The Reasons of Love (2004), tells us that love is both necessary and dangerous, making us infinitely vulnerable to each other.

Although many of those under the spell of MCS are motivated by a desire to be adored, their very practices strain the possibilities of love. By love, I do not only mean romantic love, but the kind of tender sentiments that are present among friends, family and sometimes even more distant others. This kind of other-directed love requires an openness to mutual vulnerabilities, differences and a non-instrumental conception of the beloved. Yet, MCS promotes the opposite: a kind of othering, a turning of human beings into abstract entities and instrumentally useful (or not so useful) mannequins.

Is there a ‘duty to love’ that MCS betrays? We might side with Immanuel Kant, and say that, at the very least, we must never treat people as a mere means to our own ends. But that seems insufficient when considering Camus’s declaration. To love is, in a sense, to enter into a mystery – a kind of connection with the other that offers no guarantees, no personal glory, no safe outcomes, and certainly no winners and losers. To love is to face uncertainty about who we are – and about who the other might be. Emmanuel Levinas argued that ‘alterity’ – the uncertainty born of the otherness of others – is the beginning of all morality. It might also be the beginning of all love. The other challenges us, makes demands on us, and holds us responsible. The other forces us out of our self-referential solipsism, and into the awe of connection. Look at the other’s face, Levinas tells us. In seeing the face of another, we begin to grasp what it might mean to be vulnerable, to be accountable. This is a million miles from faceless ‘Likes’, subscribers or fans.

Many attracted to life as a main character are seeking some kind of love, or approval, or reassurance that they matter. They are looking for a feeling, a vibe. But love is more than an affective stance. Erich Fromm, in The Art of Loving (1956), defines love as an artistic practice, noting that ‘individual love cannot be attained without the capacity to love one’s neighbour, without true humility, courage, faith and discipline.’ For him, love is ‘an activity, not a passive affect’ – in order to truly love, it is insufficient to merely feel; what is required is responsibility for the care of the beloved. Yet MCS denies us the ability to do exactly that – to genuinely, humbly love anyone or anything. To the conquering hero, all interactions are transactional, all awe self-directed.

Where does this leave us? MCS is not a puzzle to be solved via a ‘do and don’t’ listicle. It is not a social problem against which laws can be passed. Instead, it calls on us to engage in what Joseph Campbell, among others, called a ‘dark night of the soul’. This might mean sitting with our anonymity, solitude, boredom and lostness; pushing back on the equivocation between performance and authentic connections; making ourselves vulnerable to others, and thus to failure. It might mean seeing ourselves as always incomplete – and recognising that fulfilment might not be in the cards, that life is not a triumphant monomyth, and others are not here to be cast in supporting roles. Myself, I tend to turn to Samuel Beckett’s play Endgame (1957), where a character reminds us: ‘You’re on earth, there’s no cure for that!’ Sounds about right – let’s begin there.