I am at the beach, enjoying that elemental pleasure – walking barefoot outside, when the texture of sand slipping through my toes and crunching against the tender flesh of my sole turns walking into a kind of communion or commingling with the physical world. I am reminded of the Neil Simon play Barefoot in the Park (1967), where walking barefoot connotes the rambunctious, impulsive, back-to-nature sentiments of the 1960s, and also of Antaeus, the Greek demi-God who drew his strength from Mother Earth and was invincible, as long as he remained in physical contact with the ground.

In his poem ‘God’s Grandeur’ (1877), Gerard Manley Hopkins laments modern man’s estrangement from the divine with the lines: ‘The soil/Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.’ The beach is one of the few places where the modern human foot can comfortably achieve a state of elemental earthly contact.

But then the snack bar on the other side of the parking lot beckons. My feet, blissfully shoeless, arrive at the curb to meet a jagged expanse of sun-baked asphalt, gravelly pebbles and the remnants of smashed beer bottles, and my idyll comes to an abrupt end in a heartfelt appreciation of the purpose and power of the humble shoe.

I could walk to the snack bar barefoot, suffering physical discomfort and having my attention monopolised by negotiating the hazards. I am reminded of John McClane in Die Hard (1988), removing his shoes at the beginning of the movie and rubbing his bare toes in the plush executive carpeting of the Nakatomi Plaza, only to have this peaceful encounter interrupted by the brutal exigencies of his action-hero role, which becomes significantly more punishing for his want of footwear. Barefoot in the parking lot, my being is focused down to a pair of feet, painstakingly preoccupied with self-preservation and pain-avoidance. If I only had my trusty sneakers, all the solid ground in the world would be available to me. The quarter-inch of material between my feet and the ground would separate me from the physical earth but, in making the world accessible, would create a world too. As Shantideva, the 8th-century Buddhist monk observed, ‘with the leather soles of just my shoes, it is as though I covered the whole earth’ in leather.

This leather planet, the world created by shoes, is different from the barefoot world: detached, abstracted, insulated. It is a world less concerned with the topography of the ground and less attentive to its objects and textures. It is ‘duller’ and less ‘sensitive’. At the same time, this artificialised condition releases me from the grip of my physical circumstances and lets me ‘transcend’ the physical world toward my own desires.

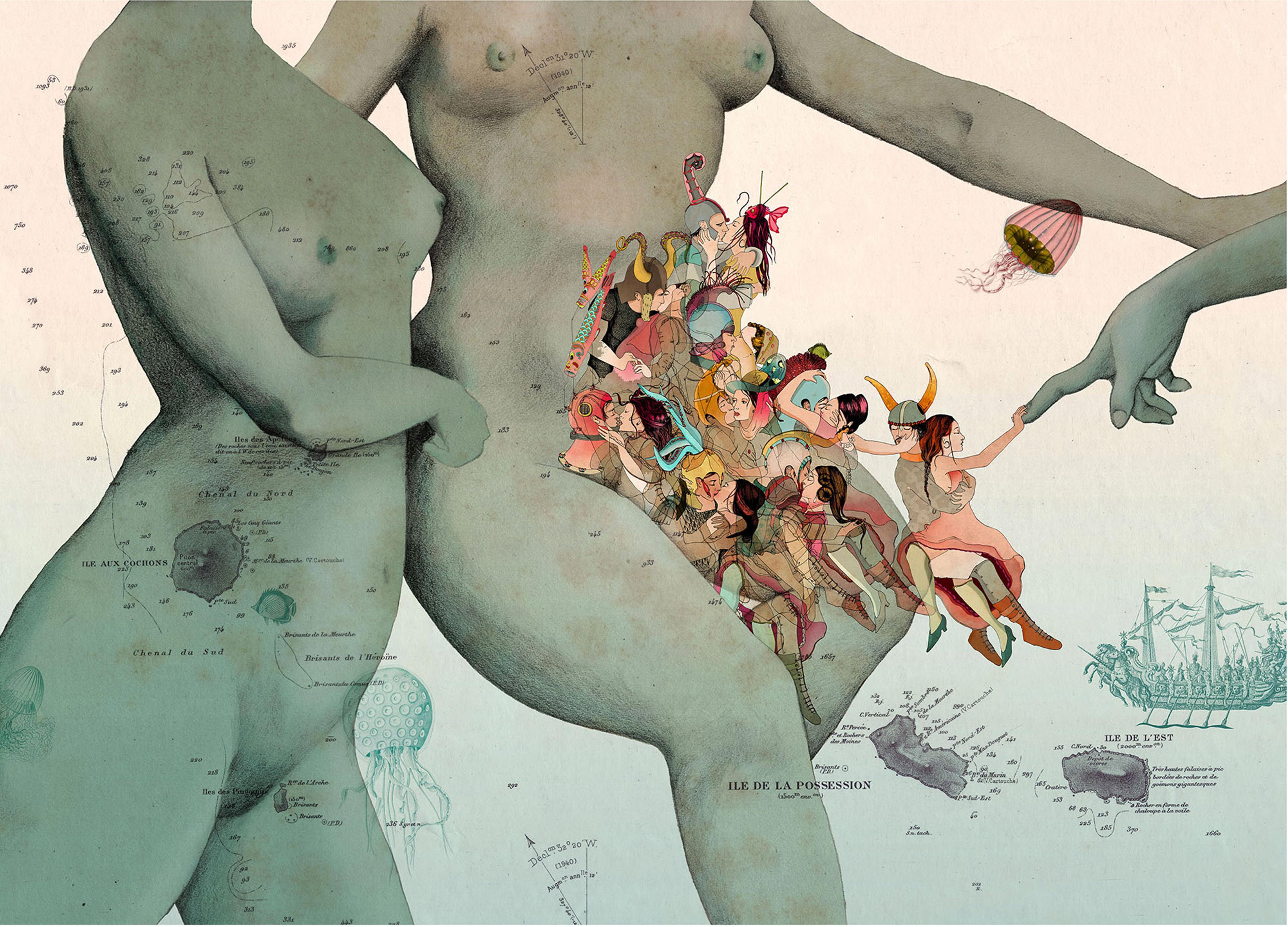

My encounter at the beach parking lot demonstrates an important aspect of how shoes exist phenomenologically for the wearer. The most fundamental thing about my shoes is not the way they look or what they do, but how they affect my mobility, my freedom and, therefore, my being. They act, even if at a subconscious level, as the literal foundation for my understanding of myself, specifically as that understanding informs my sense of where I can go – what kinds of projects are within my sphere of possible futures. This phenomenological relationship between shoes and the possibilities they facilitate informs the antifeminist trope that a woman’s ideal state is ‘barefoot and pregnant’, the ancient Chinese practice of footbinding, even modern Western fashion’s fetishisation of high-heeled women’s shoes. Impractical and/or painful shoes reduce haptic, spatial freedom even more severely than being barefoot does, reinforcing the sense in which shoes act as a symbolic foundation for human identity.

The shoe stands as a synecdoche of the wearer. To talk about being in someone’s shoes or to think about what it’s like to walk a mile in someone’s shoes, even to imagine that you have some big shoes to fill, is to contemplate stepping into a different identity – as if the shoes, not the person wearing them, determines who you are. As Elvis sang: ‘Well, you can knock me down, step in my face, slander my name all over the place,’ as long as you lay off of my shoes, my true locus of selfhood. In this subterranean way, we are our shoes.

Perhaps this is what Vincent van Gogh was trying to suggest in his repeated paintings of old pairs of shoes. During his Paris period, and at various other points in his career, the painter lavished his characteristic gift for vivid intensity on worn and cast-off footwear, creating tableaux that, although featuring shoes, seem to encompass an unseen world of meaning. The German philosopher Martin Heidegger avowed that, in Van Gogh’s painting of shoes, he could locate not only the lifeworld of the ‘peasant woman’ who supposedly wore them, but also the meaning of art itself: its ability to transport us from what he calls the ‘boringly obtrusive usualness’ of actual shoes into an encounter with ‘the thing’s general essence’. Heidegger’s commentary on Van Gogh’s painting suggests a parallel between the technologies of artistic reproduction and the technologies of footwear, both of which perform the same breaking-away from the earth to reveal the synthesis of a new world.

In the 1980s, the American cultural critic Fredric Jameson updated Heidegger’s argument, proposing that, if Van Gogh’s shoes represented the earthy, mythic humanism of modernist consciousness, then the representative shoes of the postmodern age, with its glamorous mass-produced surfaces, were Andy Warhol’s ‘Diamond Dust Shoes’ (1980) – which Jameson used as the cover image for his influential book Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991). Jameson understood that shoes are vectors of ontological mobility that carry us out of the world of immediate appearances and into the human world of signs and meanings.

The shoe, one of the oldest forms of human technology, is the prototype for all other technologies, a catch-all term for instruments and procedures that allow us to break ‘the surly bonds of earth’ and proceed into unnatural or unwelcoming environments. Vehicles such as cars, boats and rocket ships are like shoes writ large. Spacesuits, hazmat suits and vaccines are like whole-body shoes. The media of language and art can also be thought of as technologies in this sense; like shoes, they also separate us from direct experience to provide us with a new, ‘heightened’ reality. My short-lived reverie of a barefoot existence confronts me with the uncanny fact that shoes are not simply a technology that I can adopt or reject as the mood strikes me, but an artificial object my body has evolved to use.

Although the earliest artifact of footwear known to archaeology is a 10,000-year-old sandal found in Oregon, palaeoanthropologists can tell that shoes came into widespread use among human populations around 40,000 years ago because of visible changes in the skeletal structure of the small toe. Along with fire and language, shoes are one of those elemental technologies that have actually interacted with our DNA and become part of the habitat we’ve evolved to live in. My reality-check at the edge of the beach confirms that my relationship with my shoes is not merely an external relationship (between two independent entities) but an internal one, in which the shoes are in some sense part of my body. In this sense, even the most primitive technologies reveal the cyborg status of human reality. Estranged from the earth, we look to our shoes to act as a connection rather than a barrier between our physical ground and our human world.

Yet, like all technologies, shoes present a Faustian bargain: whatever advantages they bestow are always shadowed by a lingering remorse. When I return to my beach blanket, put on my sneakers, cross the parking lot and buy the beer, my thirst is quenched, but an animal resentment simmers somewhere in the recesses of my unconscious. I love my shoes. I rely on them. I am existentially dependent on them. But I also bristle at the extent of this dependency. I wonder if this vague disgruntlement accounts for the fact that even as we elevate shoes into symbols of sex, status and achievement, we also denigrate them in ways that suggest that, whereas shinier and more ‘externalised’ forms of technology let us master our environment, shoes remind us of our embodiment and evolutionary incompleteness, even as they help us mitigate these conditions.

There is in the worship of shoes a two-sidedness in which valuation and denigration are equally involved

There is a deep motif in many religious traditions according to which shoes are profane, even unholy items. When Moses discovers the burning bush, the first thing it tells him is that he needs to take off his shoes if he wants to walk on holy ground. Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus remove their shoes before entering a place of worship. John the Baptist explained his relationship to the Messiah by saying that he was not worthy to loosen the strap of his sandals. To be sure, this reputation is linked to the way shoes collect dirt and germs from the ground: bringing them into a clean interior ‘tracks up the place’, as my mom used to say. At the same time, shoes are commonly associated with the personal soil of the wearer, making the ‘stinky old shoe’ a cultural touchstone, a symbol of all that is foul and abject about the human body. When the writers of the American sitcom Married … with Children (1987-97) wanted to give Al Bundy the most humiliating job possible, they made him a shoe salesman. In the popular psychology of people who are sexually aroused by footwear, it is often observed that, in the throes of shoe-worship, what they’re really getting off on is their own self-abasement in prostrating themselves before such a menial and squalid icon.

Still, the shoe’s reputation as a debased object hasn’t prevented the global footwear market from raking in more than $200 billion a year. If you are a human being living in an even remotely technologised culture, you own a pair of shoes, and likely more than one pair. Of course, some people own many more than one pair – a surplus that’s become a notorious symbol of status. When Imelda Marcos, the First Lady of the Philippines, fled her country after the 1986 uprising, journalists breathlessly reported that she’d left behind 3,000 pairs of shoes. The figure was later revised to just above 1,000, but her love of shoes, and the media’s fascination and amplification of this love, illustrate how much cultural value is invested in footwear.

The glamor of shoes, however, is never far removed from their essential vulgarity. Reports of Marcos’s shoe collection resonated with the theme of conspicuous yuppie consumerism in the 1980s, yet appeared all the more lurid since the items in question – shoes – are considered ‘pedestrian’. Other evidence of the obscene wealth of the Marcos family – the vast estates, exotic animals, the jewellery and clothing – failed to attract the same kind of sensational outrage. When Carrie Bradshaw, the lead character in the TV series Sex and the City (1998-2004), indulges in shoe shopping as a therapeutic means of managing the pressures of urban civilisation, or when the American comedian Liam Kyle Sullivan in the persona of ‘Kelly’ sings in a YouTube video about a life devoted to buying shoes, there is a similar ironic undercurrent: these situations are comic because we sense an incongruity between the importance that shoe-fetishists invest in these objects and the ‘boringly obtrusive usualness’ typically associated with shoes. There is an undercurrent of ambivalence in the very worship of shoes, a two-sidedness in which valuation and denigration are equally involved, an ambivalence that found perfect expression in the popularity in the mid-2000s of ‘minimalist shoes’: expensive, high-tech footwear that promised to mimic the feeling of not wearing shoes at all: the self-disappearing shoe.

This two-sidedness is also evident in the key shoe-related incident of recent history. In the annals of 21st-century warfare, a significant shot was fired with ‘the shoe heard round the world’ – the moment on 14 December 2008 when the Iraqi journalist Muntadhar al-Zaidi hurled both his shoes at the US president George W Bush during a press conference in Baghdad. This sort of footwear attack has a long lineage, including Nikita Khrushchev’s shoe-banging at the UN in 1960 and the shoe bombardment meted out in 2003 to Saddam Hussein’s toppled statue in Baghdad. Although neither of al-Zaidi’s missiles actually hit its target, his act of protest deployed one of the oldest artifacts of human technology as a tool of resistance against the advanced technologies of the US military. That something as lowly and commonplace as a shoe could be used to humiliate the most powerful person on the planet seemed to epitomise the precariousness of the US’s position in Iraq. More, the episode expressed the sense in which the quotidian, earth-bound technologies used by regular folk contain a kind of resiliency that is unmatched even by the most high-tech military force in history. In its very identity as a debased and inconsequential thing, al-Zaidi’s shoe wielded a devastating potency.

The sociopolitical significance of shoes flares out in these instances in recent history. But it is in the realm of imaginative literature that the metaphorical depth of shoes has been most fully articulated. One of the most enduring cultural symbols of technological prowess are the ‘talaria’, the winged sandals worn by the messenger god Hermes, crafted by the mythological engineer Hephaestus, and loaned to Perseus to help him slay the forces of nature-magic represented by the gorgon Medusa. Incarnations of the talaria appear in the glass slippers of Cinderella and in the ruby slippers Dorothy wears in the movie The Wizard of Oz (1939). Even here, though, there are undercurrents of ambivalence about the power of the footwear. The iconic status of Cinderella’s glass slippers likely derives from the uncanny impression they create of the free-moving wearer being unshod: the slippers are in this sense the ultimate minimalist shoe. In their crystalline transparency, they whisk the heroine away from the boring ordinariness of her earth-stained world of cinders and rags into a heavenly world of privilege and freedom. But when Cinderella flees the ball at midnight, one of these magical shoes gets ‘left behind’, as if to downplay the shoes’ role in Cinderella’s traversal between these realms. In being left, the shoe is returned to the mundane world, shorn of its magic, allowing the prince to claim Cinderella beyond the enchanted domain.

In The Wizard of Oz, Glinda, the Good Witch of the North, presents Dorothy with the magical ruby slippers upon her first arrival in Oz, and she wears them throughout her ambulatory adventures in the magical realm, questing all the while to find a way back to her Kansas home. Dorothy uses the ruby slippers for walking, as she would use any ordinary pair of shoes, oblivious to their magical potency until the very end of her travels, when Glinda points out what she neglects to mention at the beginning: namely, that the ruby slippers Dorothy has been wearing all this time have the power to transport her home. Yet if Dorothy had recognised the shoes’ power from the beginning, she would never have had the transformative adventure the ruby slippers allowed her to have by way of their quotidian function as a regular pair of shoes. The potency of the shoes thus arose, at least partly, out of neglect. Both Cinderella and The Wizard of Oz dramatise an impulse to repress a conscious appreciation of the foundational role that shoes play in their wearers’ stories, suggesting that the true power of shoes lies to some degree in their ability to camouflage themselves as ordinary, unmagical objects.

A more sinister variation of the myth of the magical shoe is found in Hans Christian Andersen’s fable ‘The Red Shoes’ (1845). Anderson’s story begins when a young girl named Karen fails to show the proper respect for the metaphysical significance of footwear, glibly wearing her sexy new pair of red shoes to church. In the story, this turns out to be not only a fashion blunder but a fundamental violation of the cosmic order. Karen’s vanity is punished when she is incapable of stopping once she starts dancing in the red shoes. An angel tells her that she must dance even after she dies. She begs an executioner to chop off her feet but, even once amputated, her feet continue to dance around her, shaming Karen and keeping her barred from entering the church.

The red shoes effectively get away with murder since they are beneath suspicion

Karen’s nightmarish fate belongs every bit as much to the classic technological revenge story as those scenarios in films such as The Matrix (1999) or The Terminator (1984) in which technology turns the tables on human beings, enslaving us to its own prerogatives. The Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan in 1964 speculated that technology extends human faculties (the shoe is an extension of the foot) but also results in a ‘suicidal autoamputation’ (replacing the biological foot with a technological prosthesis). The lack of regard that Karen shows for the significance of footwear magically condemns her to live out McLuhanian theory with gruesome literalness.

In Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s film The Red Shoes (1948), drawn from Anderson’s tale, and set in a modern ballet company, the shoes themselves evince the same warning about the amputative effects of technology. A renowned director, Boris Lermontov, insists that commitment to the techne of ballet demands the rejection of any other claims on one’s humanity, and the talented ballet actress Vicky Page (Moira Shearer) is forced to choose between the technical perfection of dance and her romantic involvement with the show’s composer. When she puts on the red ballet slippers, her choice condemns her to the same fate as Karen’s – the shoes, apparently by themselves, begin to twitch and jerk, carrying Vicky off a balcony and under the wheels of an oncoming train. In the wake of her death, the ballet company performs a ballet of ‘The Red Shoes’ with an empty spotlight standing in for Vicky, as if she has been existentially amputated from her own story. The camera’s focus on Vicky’s shoes as she makes her suicidal leap signals to the audience that they, not the wearer, are in control; manipulating their wearer in accordance with their own inscrutable purposes; all of the characters in the movie likely suspect that Vicky acted ‘on her own’. The shoes effectively get away with murder since they are beneath suspicion.

We are all Cinderellas and Dorothys, Karens and Vickys, whisked along toward our futures by the magical power of our footwear, while being disdainful, neglectful and forgetful of the shoes themselves. In a critical episode in Don DeLillo’s novel Underworld (1997), a Jesuit priest attempts to re-educate Nick Shay, a juvenile delinquent, to appreciate the interdependency of language and perception. Father Paulus laments that too much of the education provided to young people focuses on abstract ideas: ‘Eternal verities left and right. You’d be better served looking at your shoe and naming the parts.’ When challenged to name the parts of his own shoe, Nick is able to identify the laces, the sole and the tongue, but the priest challenges him to look more closely to identify the cuff, counter, quarter, welt, eyelet, aglet and grommet.

Father Paulus presents the lowly shoe as the object that exists on the extreme opposite end of the continuum from the realm of transcendent ideas that Jesuit priests supposedly concern themselves with; but when the object is inspected in greater detail, it reveals a hidden intricacy, a universe of language and history that we see every day but still fail to perceive. Learning to appreciate this intricacy is a crucial step in Nick’s education, and it is precisely because of the humble obscurity of the shoe as an object that it is capable of becoming a symbol of a wider world that percolates below the threshold of ordinary perception.

The shoe sits at an uncanny ontological threshold: partly belonging to the earth, partly a piece of our own bodies. It’s an object that separates us from the earth while also opening up a world to us. It is simultaneously revered and trivialised in ways that seem to hinge, paradoxically, on one another. Not least, the way we think and feel about shoes rebounds on our own self-perception, both as individuals and as a largely shoe-wearing species. Those points of ambivalence are revealing because they expose elemental conflicts about our own relationship with nature, technology and our bodies: shoeless at the beach’s edge, I felt liberated from social confinement but also, strangely, stripped of my possibilities – as if I had left, along with my shoes, my self behind. Now, reshod, my feet and my selfhood can return to their carapace – secured and corseted, and ensconced in the soft numbness of leather-world.