Sometime in the 1220s CE, a young woman named Ida was walking the city streets of Leuven in Belgium when she was called into the home of a dying man. The sick man was so certain of his imminent death that he had already summoned a priest to administer last rites. Entering his home and having learned something of his affliction – its duration, symptoms and the source of his pain – Ida fixed her eye upon the pestiferous tumour that vexed him. She promptly drained the tumour of its puss and – lo! – the man reported immediate results. The swelling and pain had diminished with Ida’s assistance. He made a full recovery.

Ideas about medieval medicine often conjure images of men donning plague masks, carrying leech flasks, and sporting an assortment of backwards, painful and toxic remedies. Rarely do we imagine stories such as this one, of a woman’s bedside ministrations. But the history of medieval medicine is one that might best be told from the perspective of quotidian acts of care. Hundreds of devout single women just like Ida dedicated their lives to active charity in which they cared for the poor, sick and indigent in private homes, in hospitals and on city streets. Some of them acted as official caregivers who served as midwives or wetnurses, as nursing sisters in hospitals, or as nuns who maintained apothecary shops. Others bore no official titles whatsoever and charged no fees for their service. The kind of care they provided has remained invisible, though it was as essential to daily life in Europe as economic transactions, religious and civic festivities and the waging of wars that feature so prominently in our records of the Middle Ages. What is remarkable about Ida’s story, then, is not that she cared for this dying man in Leuven, but that it was recorded at all (in this case, by an unknown Cistercian monk).

Women were prominent in everyday care because healthcare was largely a preventative enterprise that took place in domestic, interior settings. Medical knowledge was as dynamic and fluid then as now, but therapeutic ideas from the Middle Ages were often transmitted through oral means as well as through informal, apprenticed training. The human body was commonly understood to consist of four fluid humours – blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile – that fluctuated in relation and proportion to various internal and external factors. Since health and illness largely depended on humoral excesses or deficiencies, the task of health practitioners was to moderate the humours in search of balance. They tinkered with humoral flow through bloodletting, emetics, purgation and other manipulations of the body.

It was largely understood that what took place inside the body was dependent upon its interactions with factors that originated from outside of the body. In medical theory, these external factors were called the non-naturals. The non-naturals were divided into six basic categories. The first was air, which we might think of as the quality of the environment. Next was food and drink – not just the diet as we know it, with its quantities, quality and specific component ingredients – but also the manner by which certain alimentations warmed or cooled, accelerated or decelerated the motions of the fluid economy within the body. The next two categories – exercise and rest, and sleep and wakefulness – have clear contemporary parallels that are still recognisable for their effects on health. As a fifth category, the likewise familiar concepts of evacuation and retention referred to the rate of a patient’s urination and bowel movements. And finally, there were the passions of the soul.

These passions were akin to emotions. According to medical theorists, certain strong emotions could trigger physical effects as witnessed in the blushing caused by embarrassment or the shivers generated by fear. Intense bouts of sadness, anger or longing could precipitate deleterious conditions such as melancholia (severe depression) or acedia (utter languish). In such cases, practitioners might prescribe remedies intended to delight and soothe, such as listening to the delicate sounds of pleasant music, observing the soothing sensations of the garden, engaging in amusing conversation, or taking pleasure in a jovial story. These experiences might relax or tense the body, and cause the circulation of heat away from or toward the heart. This stimulation caused an adjustment to the humours that produced physical manifestations.

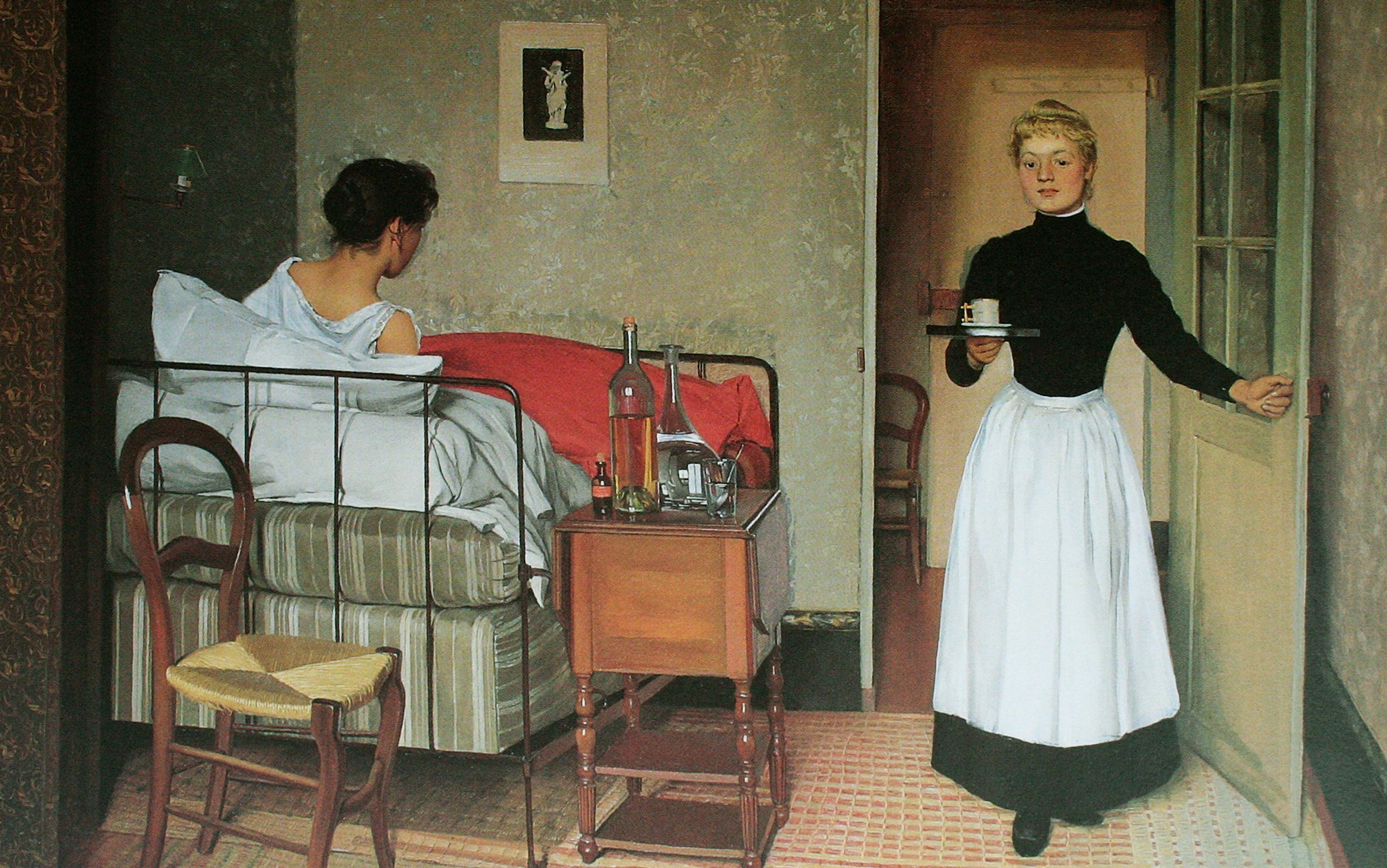

Taken together, the six non-naturals represented the body’s total environmental context – the food it ate, the air it breathed, the media it consumed, the amount of exercise, sleep and purging. Regulating this context on a daily basis was largely women’s work. As mothers, sisters, wives and daughters, women prepared meals, laundered linens, ensured regular exercise, soothed emotions and generally maintained the regimen of their charges. In most cases, the maintenance of non-natural health took place within the home in informal and intimate settings. But when the body’s vulnerability exceeded domestic resources in Christian communities in Europe – such as when childbirth became especially woeful, when travellers wandered in faraway lands, or when disease wasted limbs – it was often religious women who took up the care responsibilities that filial relations could no longer bear.

Prayer to St Apollonia was one of the most common forms of dental assistance, recommended by physicians

For example, in the town of Huy, in present-day Belgium, a woman named Yvette provided routine care in the leprosarium known as Grandes Malades. There, she fed and bathed patients, and checked on them in the middle of the night to adjust their position in bed. She made it clear to friends and neighbours that she wished to provide assistance to those ‘vilest persons’ that family and society would no longer accommodate. Other religious women dedicated themselves to ensuring that the sick had access to necessary material resources that they were unable to procure for themselves, including food, blankets and medicine. An Italian widow, Umiliana of Cerchi, begged in the streets of Florence to provide resources for the sick poor. And Ida of Nivelles, who would later become a Cistercian nun, spent her youth begging for bread, cheese, footwear and medicines on behalf of patients in the hospital of St Nicholas.

These material comforts were often accompanied by spiritual and emotional consolation – attention to the passions of the soul. For instance, when Ida of Leuven found herself ill and bedridden, her sister not only brought her bread and oversaw her regimen, but also took her for walks and provided soothing conversation. When the preacher and abbot John of Cantimpré felt he was nearing his death, he requested that he be transported to the convent of Prémy, where he sought the prayerful presence of nuns. And when the young Bernard of Clairvaux was beset by severe headaches, his mother arranged for a woman to sing to him to ease his suffering.

Communities in late-medieval Europe valued religious women for their physical acts of caregiving as well as for the therapeutic quality of their songs and prayers – that is, their intense performance of powerful words. Ample medical charms, poems, hymns and prayers have survived from women’s religious communities, a testament to their involvement in the therapeutic care of the passions of the soul. Take the example of a book of prayers, known as a psalter, from a community of religious women in Liège who served a local hospital. Now housed in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, the psalter contains, in addition to the psalms, a monthly guide to a regimen of healthy foods and beverages that women could refer to when preparing salubrious meals and scheduling phlebotomies. The book also features a set of poems perfectly suited for performance at the bedside of the sick. They cite specific remedies such as theriac, a medieval wonder drug consisting of numerous compounded ingredients, while integrating interjections to ‘heal the sick man’ and ‘heal all pain’. These poems might have been read at the bedsides of the sick in the hospital of St Christopher in Liège, where the sonic and rhythmic delights might encourage patients’ hope and joy, which would in turn contribute to recovery or at least to resilience.

Another prayerbook from the same community, now in the British Library in London, includes prayers to St Sebastian. Homage to this martyr and plague saint was, by the 14th century, considered one of the most efficacious remedies for this affliction. Another prayer in the psalter calls on the martyr St Apollonia for the alleviation of toothache; prayer to her was one of the most common forms of dental assistance, recommended by physicians as well as village empirics. These prayers, dedicated to specific therapeutic purposes, indicate a wider environment in which religious women were concerned with providing comfort and healing to their community members.

Other devotional books made for women’s religious communities furnish additional evidence for the kinds of healthcare labour they provided. Some of these books contain medical charms and indulgences that would be used as aids in caregiving. Charms were verbal remedies that were written or uttered on behalf of the patient, and were used by many varieties of healthcare practitioner. In a 14th-century manuscript from the Cistercian women’s abbey of La Cambre in Belgium, a series of charms were inscribed to support the care of those experiencing childbirth and epilepsy, an indication that the nuns and laysisters in the community likely served in this capacity. In another book used by Cistercian women, an indulgence is copied for protection in childbirth and is attached to apotropaic drawings of the side wound and arms of Christ, that is, the instruments of torture described in the gospel narrative of Jesus’ suffering and death as well as the lacerations they produced.

Such indulgenced images might have been used as assistive devices in childbirth, similar to the birth girdles that the parturient were known to wrap around their bellies during labour. A recent study of ancient proteins left on the parchment of a 15th-century English birth girdle has shown that such devices bear traces of their use. The girdle retains remnants of blood and other bodily fluids that would have been expelled during labour, and also preserves traces of foodstuffs such as honey and oats that would have been used to care for the woman. In such items, we see how religious women supported others during life-threatening circumstances by bestowing physical comforts such as neutral foods and massage, but also by providing prayer and poetic chants that might be adapted to the pace of labour, speeding up or slowing down to sync with the rhythms of contraction in a meditative, incantation-like formation.

Research by the American historian Monica H Green shows that, while women in the Middle Ages clearly provided essential healthcare services, their labour then, as now, was virtually invisible to anyone looking only to official records. For example, scholars digging into national records of official – that is, licensed – healers, have found scant evidence of female practitioners: according to those records, women represent fewer than 2 per cent of the total recorded practitioners in late-medieval France and England, and even fewer in Iberia’s Kingdom of Aragon, the regions for which we have firm numbers. In addition, the question of what constituted ‘official’ medical practice was highly contested in the Middle Ages, such that therapeutic authority – which practitioners were perceived as possessing the power to heal – was dependent on the individual community, the individual practitioner and their relationship, their history.

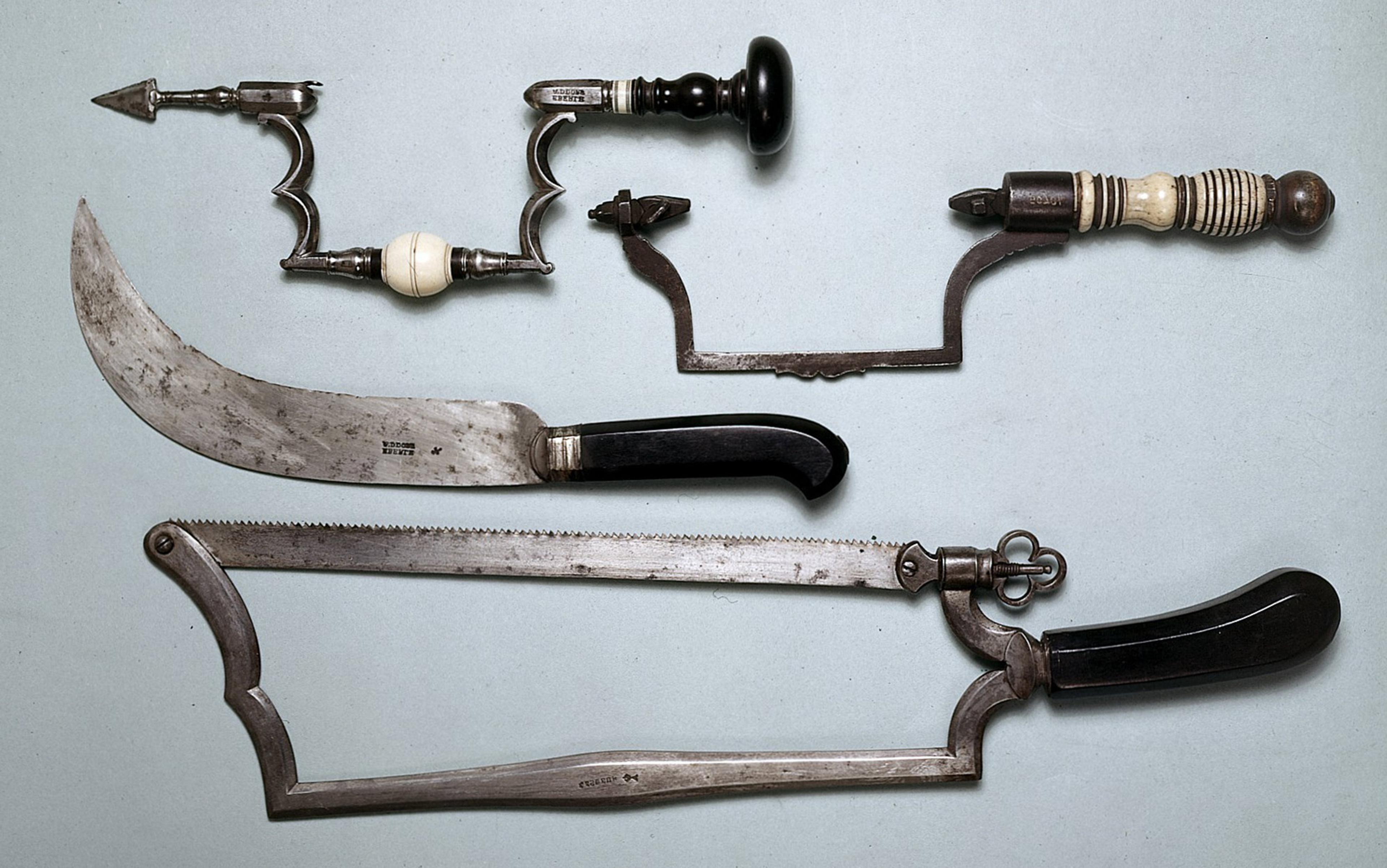

In this social context, a variety of specialists competed for authority in the medieval medical marketplace – from scholastic physicians, herbalists, barbers, apothecaries and surgeons, to village empirics, saints and charitable women. So, if licensed, university-educated male physicians were to emerge at the pinnacle of this hierarchy, they would need to furnish some kind of justification for their claim to authority because they were not able to demonstrate greater efficacy or access. According to the humoral model of the body, after all, most medical care was preventative. And, if the majority of medieval medicine was preventative, and women controlled the means of domestic production and reproduction – food, sleep, hygiene and emotional wellbeing – then in some real sense women were the greatest threat to a medical elite who sought to elevate their own practices and differentiate them from common household chores.

One way that physicians sought to distinguish their practices from those of women was by caricaturing women healers as chatty, gullible hacks who spout futile words and wield spurious herbs. They were careful in doing so, as they wished to retain for themselves some of the very practices that they accused women of engaging in improperly. Authority in matters of healthcare came to be conditioned by gender, in addition to factors such as race, ethnicity, class and ability, among other social markers of identity and status. For example, the 10th-century physician Qūsta ibn Lūqā, whose work was influential among scholastic physicians, recommended a range of therapies to cure melancholy, including listening to music, engaging in pleasant conversation and luxuriating in warm baths. He composed a parade of bizarre therapeutic agents for other physical ailments: meat-coloured carnelian (a gemstone) to staunch blood, the faeces of a wolf who had consumed the bones of a sheep for an upset stomach, or an emerald worn on the finger to prevent epileptic seizures. Qūsta insisted that, if a physician provided the patient with an amulet or charms along with any herbal remedies prescribed, then such embellishments would work to encourage patients’ faith and hope in a cure, which would, in turn, support their bodily health.

Women, the elderly, children and people from Ethiopia and Scotland should not be trusted with such remedies

Hope was understood to expedite the process of healing. Charms and amulets supplied the medical theatrics and props that worked on the passions of the soul by encouraging genuine hope for cure. Therapeutic authority depended on a convincing performance, and the practitioner’s ability to elicit from patients a genuine faith in the power to heal. As Qūsta reasoned: ‘health will follow more quickly, since the body is aided by medicine [and] the soul by an incantation, in which the joining of the two health for body will follow more rapidly.’ But, he continues, only certain practitioners were truly effective and trustworthy at deploying verbal and empirical treatments. Women, the elderly, children and the extremely light- and dark-skinned people from excessively warm and cold climates such as Ethiopia and Scotland, he asserted, should not be trusted with such remedies.

The first generation of educated, licensed medical practitioners who claimed authority over matters of human health in the West ensured that social markers were essential to the perception of therapeutic efficacy. Italian physicians inherited Islamicate medical texts and began tinkering with the notion that hope and confidence in cure encouraged the therapeutic process, and that men, rather than women, were best suited for the job. The 13th-century Italian physician Urso of Salerno suggested that only the trustworthy virtue of the educated male could elicit the proper measure of confidence to commence the healing process, through their soothing words and hope-inspiring presence. His countryman Peter of Abano argued that a patient’s mere confidence in their practitioner bore real bodily effects. The physician’s ability to convince the patient, to play on their capacity for hope in cure, cinched the salubrious process. For Peter, too, the remedies hocked by practitioners other than educated men were to be greeted with suspicion; old women, he warned, were subject to demonic intervention when uttering therapeutic charms. And for the mirabilis doctor Roger Bacon, the power to heal bodies by the virtue of one’s soul was given ‘especially [to] young men’ who could comfort by their mere presence.

By the late Middle Ages in Europe, as practitioners of medicine were outlining the parameters of their field, physicians deemed that women, the uneducated, countryfolk and non-Christians were inept charlatans who sought to prey on the false hope of desperate patients. They created a smear campaign to ensure that potential patients doubted their therapeutic authority. The French physician Guy of Chauliac declared that ‘women and idiots’ were most interested in using herbal charms and incantations. And the surgeon Theodorico Borgognoni swore that the ritual prayer he recommended for extracting an embedded arrow was derived from learned male physicians, and not from the false tales of old country women.

Physicians also sought to limn their competitors by issuing and policing licences to practise medicine. The case of Jacoba of Felice is instructive. In 1322, the medical faculty at the University of Paris put Jacoba on trial. Her alleged crime: practising medicine without a licence. The minutes of the trial are revelatory, indicating that patients often turned to Jacoba after having sought remedy from licensed medical practitioners who were unable to cure them. One witness reported having been so sickly that he could not stand or walk. He consulted numerous medical doctors before he finally called for Jacoba to visit him at his Paris hospital. Jacoba prepared purgatives, wrapped him in bandages and ointments, and rested him in a herbal sweat bath, all of which she undertook ‘with such great care that he was completely restored to health’. Another witness testified that she was so ill that several consulting physicians had already given her up for dead when Jacoba showed up to assist. Jacoba ‘laboured over her’ by inspecting the woman’s urine and feeling her pulse, then she prescribed a liquid medicine and a purgative syrup. The physicians who put Jacoba on trial could find nothing wrong with her diagnostics or prescriptions. Nevertheless, she was found guilty and barred from ever caring for the sick again.

Jacoba’s trial alerts us to the difficulties that women faced in trying to practise healthcare without a licence. Because the barriers to acquiring a licence were so great, many did what they could to help neighbours and family without a licence. But financial and social hindrances also explain why unlicensed practitioners are so difficult to track in the historic record. The practitioners who provided everyday care in the Middle Ages can’t be searched for in our historical databases according to licences, occupational markers and even fee-for-service exchanges. Instead, we must look for women’s soothing presence away from clinical spaces, in the intimate places that sick bodies sought care and reported cure. There, we find the subtle interventions of daily regimen and attention to comforting the passions of the soul as integral components of healthcare.

A history of healthcare conceived from the vantage of care, rather than that of authoritative practitioners, reveals a pattern that has been replicated over the centuries: the care that is most daily, most sustaining to all other acts, is also often the most undervalued, the most invisible and the most feminised. Recently, scholars have begun to dismantle histories of medicine that imagine the construction of health knowledge from the limited perspective of the authoritative practitioner. Their findings shatter our image of the solitary, typically white, male physician-healer, and foreground the extent to which health outcomes and health knowledge are dependent on daily acts of care.

These women supplied the bodies on which white male physicians staked their gynaecological research

The historian Sharon Strocchia at Emory University in Atlanta has significantly expanded the theatre of healthcare practice, as well as its dramatis personae, by demonstrating the pervasive healthcare networks established and maintained by early modern Italian nuns. Religious women, she shows, acted as ‘agents of health’ in courts, convents and hospitals, where they developed pharmaceutical and medical technologies that were transmitted both locally and far beyond communal and political boundaries. The historian Deirdre Cooper Owens at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has revealed that the labour of enslaved women in Alabama in the 19th century created the circumstances and produced the knowledge that resulted in historic breakthroughs in gynaecological surgeries, including caesarean sections, ovariotomies and procedures for obstetric and vesicovaginal fistulas. Using their knowledge as nurses and midwives, these women performed crucial tasks in experimental surgeries, provided recovery care for patients, and supplied the bodies on which white male physicians staked their gynaecological research.

Beyond these Western models, scholars are reframing what counts as medicine and healthcare, pointing readers toward a range of therapeutic and caregiving practices that shape experiences of health, illness and disability. The medical historian Ahmed Ragab at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, for example, has outlined how traditions of prophetic medicine and religious conceptualisations of health and disease in medieval Islam conditioned both medical practice and patient response. Meanwhile, the scholar Dwaipayan Banerjee at MIT has exposed the failure of biomedical systems to recognise and relieve the suffering of impoverished cancer patients in contemporary Delhi; even when care networks are available within the household, ‘infrastructural duress’ exacerbates precarity. These studies, undertaken from the perspective of embodied experience and decentralised healthcare delivery, have provided scholars and activists with the opportunity to assert a new politics of care.

Such a politics is a matter of urgency. The devastating effects of COVID-19 have brought greater public attention to this centuries-long pattern of inequity in healthcare systems. According to the Brookings Institution, 81 per cent of all workers in the healthcare and social service industry in the US are women, and they are disproportionately women of colour. Women make up nine out of 10 nurses and nursing assistants, most respiratory assistants and home health aides, and a majority of pharmacy aides and technicians. They provide housekeeping, food preparation, patient care, and maintenance. Their work is essential to the smooth operation of the entire economy and healthcare industry, in and out of pandemic times. Yet it is underpaid and undervalued, with at least 20 per cent of essential healthcare workers living in poverty.

We know about Ida of Leuven, who pierced the dying man’s tumour to revive him, because a small community of followers venerated her as an unofficial saint and recorded her feats of charitable care and cure after her death, first in orally circulating stories, then later in writing. The deep history of care might suggest to us that we desist in waiting until caregivers are gone before we recognise their labour, build their shrines, tell their stories.