I’m lying on my bed, on my back, with a bandage wrapped around my head. If I had a thermometer sticking out of my mouth, I’d look like an emoji for a sick person. There’s nothing wrong with me, at least nothing the bandage can fix, but there are two electrodes under it — one above my right eyebrow, the other higher up, beyond the hairline above my left eyebrow. They’re supposed to be making me smarter, or so the internet says. The eyebrow alignment thing is clutch because it’s hard to know exactly where to plant the anode and cathode, and placement is key if you want this thing to work.

I can’t tell if it’s helping me yet. Before I got into any of this, I expected a raging placebo effect. I’m a sucker when it comes to under-explored human potential and ‘stuff that makes you be better’. I like science a whole bunch, but I love The X-Files more — I want to believe. A year ago I quit smoking and started running, which is universally understood as good, but now I eat chia seeds, coconut oil, and dinosaur kale, too, and I buy into sensory deprivation tanks. I don’t eat gluten or dairy (except KerryGold butter) and listen to quite a few podcasts about the Quantified Self. I roll my eyes at the grandstanding blowhards who have ‘fixed’ themselves but I keep up with the gizmos and apps that track people’s various rhythms. I’m no lifelogger or body-hacker, but I’m curious, and I want to be in-tune enough to know what’s really the matter, so I can level up and be at my most awesome.

Right now, though, my concerns are superficial: I’m worried about my pillows. I’m using wet, Post-it sized sponges to help conduct the electricity that’s making its way into my skull, but I overdid it. The waterlogged squares are weeping all over my face and into my down pillows, and those are fancy and newish, so I don’t want them to start smelling weird. I don’t know what it means that I’m so concerned with my bedding, but I’m hoping this session will figure that out for me. The water juices the current so it doesn’t run out of steam while it’s lapping my head, but it’s also there as a precaution: I don’t want to burn myself like this one guy on Reddit who has a forehead patch that looks like a hamburger. However, this is my fourth day of auto-administering TDCS, or transcranial direct current stimulation, and I’m slightly discouraged. It sucks to admit this, but I may need TDCS to be intuitive enough to do TDCS correctly in the first place.

Few things make you feel more irresponsible than relying on a subreddit for information on zapping your brain. To catch you up on everything I know, TDCS (or tDCS — there’s something controversial about whether the ‘t’ should be capitalised or not, but I’m a tourist so I’m sticking with a big ‘T’ because it’s easier) is also called non-invasive brain stimulation. It’s non-invasive because nobody’s getting cut open. If you break all the words down it means you’re sending electricity through your head where it turns on, stays on for a while — usually 20 minutes — and then shuts off. During the session, the bit of brain directly beneath the anode (in my case, the red wire) is thought to become excited, whereas the region beneath the cathode (the black one) is thought to be inhibited.

If you’re thinking of TDCS in terms of electroconvulsive therapy, like in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Girl Interrupted, it’s not like that. Dr Marom Bikson, associate professor of biomedical engineering at the City University of New York, explained it to me like this: ‘The way to think about electrical stimulation is that you have a dose, just like with a drug. But instead of talking about what the drug is made out of in terms of chemical composition, we talk about the waveform, duration, and placement. Any alterations make it a different drug altogether.’ TDCS is two milliamps, ECT about 800. See, super-different.

Bikson has been studying the effects of electric currents on neurons since he did his dissertation on the subject at Johns Hopkins in 1995. He’s the guy TDCS fanboys email all the time, asking questions or writing screeds about their discoveries and adventures. He has dynamite SEO when you look for anything TDCS-related, especially in New York. He’s also the CEO of Soterix, which is like the Louis Vuitton of TDCS machine manufacturers. At Soterix, they have that whole ‘price available on request’ thing going on, like you see in high-fashion magazines. He won’t even tell you how much one costs since there’s no way to get one outside of a research setting.

Part of me wonders if everyone who undergoes TDCS will go nuts in 50 years, in the same way I’m slightly convinced everyone with LASIK will go blind on the very same day.

When I visited Bikson at his office uptown to check out the gear, I asked him to run a session of TDCS on me, but he shut me down. He did let me feel the current on my arm, at which point I sweet-talked him into showing me what it felt like on my head. But only for a minute. We both knew there are minimal risks to TDCS since we’re talking teeny, tiny electrical currents, but he could lose his job running experiments on randoms so I understood. I didn’t flip his desk or set fire to his office.

The funny thing about TDCS is that I’d never heard of it until I did, but once I had it started showing up everywhere. It’s like that movie with Jim Carrey where he sees the number 23 wherever he looks, but less boring. The articles on the topic are wonderfully seductive and because I’m such a believer I buy into most of them. The ones from British newspapers are my favourites. They crib juicy bits from clinical trials in Brazil or Germany, or else DARPA experiments, and pull-quote on and on about how TDCS makes you smarter by ramping up your maths skills and language skills, while giving you laserlike focus.

It’s also supposed to improve marksmanship. Last year, Sally Adee wrote an article on TDCS for New Scientist. She visited a lab in Carlsbad, California where they hooked her up to a machine intended to evoke a ‘flow state,’ that Zen zone where you tune-out self-doubt. She said it helped her learn how to shoot an M4 close-range assault rifle in a military training simulation. The first go around, she was garbage at it, but when she used TDCS she found herself in a state that she described as a ‘near-spiritual experience’ and slayed every single one of the targets. Reading her story, I was reminded of the immortal words of 30 Rock‘s Liz Lemon: ‘I want to go to there.’

The godfathers of modern TDCS are Dr Michael A Nitsche and Dr Walter Paulus from the department of clinical neurophysiology at the University of Göttingen in Germany. In the year 2000, Nitsche and Paulus published an article in The Journal of Physiology, which described how TDCS alters excitability in different regions of the brain by up to 40 per cent. In the brain, excitability affects synaptic plasticity, which means that the neural pathways that determine the capacity for memory and learning are changing substantially, depending on where you’re zapping. There are various electrode montages, each correlating to what we understand about regions in the brain. If you want to stimulate the language centre, you place your anode and cathode on different parts of your head than if you’re interested in reducing epileptic seizures. It seems straightforward but it’s actually mysterious. For example, stimulating the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex influences memory but also helps you quit smoking.

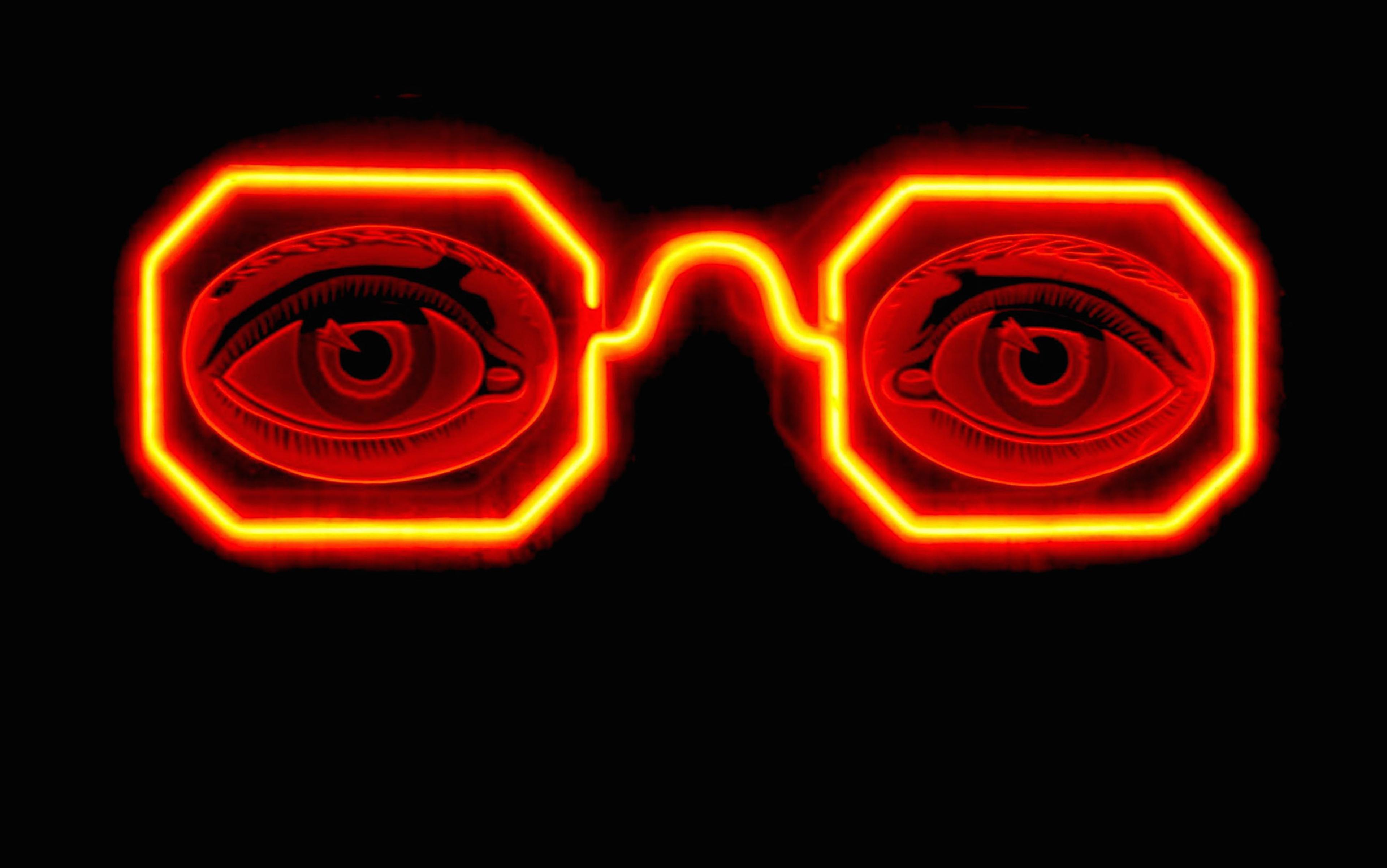

Most of the recent internet write-ups on TDCS have been about the ‘foc.us’, a TDCS headset that claims to ‘overclock’ your brain and make you better at video games. Priced at $249, the unit comes in two colours (red and black) with a fancy zippered carrying case like the kind that overhyped headphones made by ex-rappers are packaged in. They’re beleaguered with shipping issues and have fallen a couple of weeks behind in fulfilling orders (mine has not arrived yet) but their customer service is highly communicative. The website is a riot. In the ‘press’ section, there’s a handful of high-resolution images with attractive models wearing the headset with Blue Steel expressions, very low-cut jeans, and ‘come hither’ eyes. It’s clear this stuff is marketed to gamer bros, but from what little I know, I’m not convinced of the effectiveness based on the foc.us contact points. The sponges are too small and flat and the headset looks hard, like a girl’s plastic headband. I can’t imagine the electrodes are placed snugly enough on the skin to guarantee an effective circuit.

Advertising image for the foc.us gaming headset, slogan: ‘Overclock your head!’ Credit foc.us tDCS Labs

Despite my scepticism, and the fact that I don’t even know what it means to ‘overclock’ the brain, I’m intrigued. After all, the desire to make yourself smarter is universal, and in my experience, if you’re smart in the first place, you’re even greedier for cognitive boosts. When I get writer’s block, I’ll do almost anything to get over it. Sometimes, I even give a guy money to let me lie in the dark in his saline-filled tank. The only thing I won’t do is noortropics. Smart drugs scare me. Especially ProVigil (Modafinil), the pill that’s referred to as the ‘Limitless’ drug since it behaves like NZT-48, the brain-boosting stuff that takes a doltish Bradley Cooper and makes him superhuman-smart. Certain overachieving Silicon Valley types are candid about taking it regularly, like Dave Asprey, aka The Bulletproof Executive, who also cops to augmenting his chemically heightened brain function and alertness with TDCS. He’s had a kit for over a decade, and he throws it on like a light cardigan whenever he feels like it. He claims it allows him to efficiently reach ‘gamma states,’ a transcendental level that takes the Dalai Lama four hours of meditation to achieve. I know this because he talked about it on Joe Rogan.

I’m going to try to learn how to twirl a pen, in a practice known in Japan as mawashi. It’s otherwise known as that annoying but enviable gift that all Asian mathletes seem to have

I like Asprey’s casual style, but part of me wonders if everyone who undergoes TDCS will go nuts in 50 years, in the same way I’m slightly convinced everyone with LASIK will go blind on the very same day like in that José Saramago book. Still, I have to at least do it once. And by once I mean five days a week for two weeks at least. How else will I know? But the thing about TDCS is that nobody will do it on me outside of a clinical trial. Most of the clinical trials currently being conducted in the US focus on stroke rehabilitation and pain management. There are also some interesting attempts to treat depression with it, and there’s a team at Harvard that’s looking into the effects of TDCS on food cravings. That’s the study I’m really curious about, since I have a Dorito problem, and because it’s being led by Dr Felipe Fregni, who is a big deal in TDCS circles. But the problem with clinical trials is that most are double-blind with a sham arm, which means neither the subject nor the investigator knows who got the real treatment. Even if I hoof it to Boston for a couple days a week, there’s no guarantee I’ll be juiced. And while there’s a study at the University of Pennsylvania, I’m not eligible for it, because English is not my first language.

At this point, I’ve been researching TDCS for weeks and reading a ton of Oliver Sacks. I’ve re-watched Altered States and even screened the Bourne Identity again, the crap one with Jeremy Renner where he takes the ‘blue chems’ to get smart. I am jonesing for a vision quest or that quickening that’ll happen when my synapses get diesel and my long-term potentiation game is unrivalled. But there are just too many caveats when you’re working within the parameters of clinical research with institutional review board approval. I’m getting antsy, but I’m still determined to go the official route. I finally succeed in finding an assistant professor of neurology at New York University who agrees to administer a 20-minute sample session. She warns me that a single dose is ‘not likely to produce any long-lasting changes’ but still, I take her up on it, because I want to see the electrode montage and get a feel for the experience as a whole. The morning of our appointment, she goes into labour and emails me as she’s headed to the hospital.

I feel like the universe is trying to tell me something, so I take matters into my own hands. I do not visit the campuses of pedigreed universities, I go to the TDCS outback. I head south to visit Dr James Fugedy at the Brain Stimulation Clinic in Atlanta, Georgia. It’s the one place in the country where you’re able to buy a TDCS machine of your very own. Fingers crossed it’s not in a strip mall.

I’m happy to learn that the Brain Stimulation Clinic is well-appointed and official-looking. I hadn’t known what to expect, since the website is helpful but also features a lot of cursive type. The clinic is located on the third floor of the Meridian Mark Medical Plaza and I’m admittedly most reassured by the multi-storey parking garage. The way I see it, the true indication of how official the BSC is, is if they validate parking. It’s humid out since it’s been pouring all morning and I’m in black leggings and a loosefitting top. I’ve come all this way to see Fugedy and here I am dressed like I’m going to yoga. I snap a photo of my crap rental car and the spot I’ve parked it in, just in case my zapped brain elects to jettison this information. I wonder briefly if I should be driving myself home, given that you’re not allowed to after oral surgery or getting your pupils dilated.

Fugedy’s office has a waiting room that’s large by New York standards. I fill out the paperwork about my medical history and insurance information. A BSC visit with a single treatment is $150, but an appointment where you’re given a treatment, your own TDCS machine to take home and instructions on how to use it (as well as follow-up emails or Skype chats) costs $2,400. Insurance doesn’t cover it since the treatment is ‘off-label’ which means that TDCS isn’t approved for the depression or fibromyalgia you may be visiting Fugedy for. But sometimes for patients with insurance and a well-documented pain-management case, Fugedy will perform electromedicine on your body, bill the insurance company (since that’s FDA approved) and deduct the session fee from the $2,400. Fugedy refuses to sell a unit unless you meet with him in person. He has standards. He went to Yale.

I’m led by a nurse to the back office which has three huge windows, a brown exam table, two small, suspiciously identical plants (they’re plastic, I checked), a framed painting of a non-religious mother and child, and a grey machine with a bunch of dials and buttons on it. Fugedy looks about in his 60s with a thick head of stick-straight white hair and a white moustache. He takes my vitals and we chat about our respective weeks. I like him immediately. He’s one of those guys who never seem put out, no matter how many questions you ask him.

Amid my frustration, I start to wonder if TDCS makes you better at sex. I’m unnerved that this is where my brain went, even if I’m definitely not the first person to consider it

The TDCS machine that Fugedy uses is called an ActivaDoseII Iontophoresis delivery unit. As he readies it and wets the sponges, I realise I’m nervous. I have such high hopes. I’m already kinda good at a whole bunch of stuff. I wonder if it’ll be hard for me to relate to people who aren’t as accelerated as I am. I’ll have to break up with my boyfriend and stop talking to my family because the alternative would only hurt everyone. I’ll be like Dr Manhattan from Watchmen. I’ll probably have to go to space just to get some peace.

The set-up turns out to be rather simple. The unit is about the size and weight of the first-gen Game Boy, but black. There are only two dials, one that’s the on/off switch and one that controls the current. The hard part is placing the electrodes. I make sure to take selfies of the electrode montages so I can know if I’ve done them correctly when I get home.

One of the first things I notice about TDCS is that it’s like being able to set an appointment for a power nap. Time goes by at an unbelievable clip. Twenty minutes is a long time just to sit near someone blinking at you, so Fugedy leaves the room. He gives me a big gold Salvation Army bell so I can alert him when the 20 minutes are up. When he comes back into the room, I think he must have forgotten something. It feels like only five minutes, but it turns out 19 have already passed. I’m even slightly annoyed, as if I’ve been interrupted.

TDCS sort of feels like you’re about to fall asleep while knowing that you won’t completely conk out. My breathing slowed way down, and I started to feel cold. I was so relaxed, I couldn’t imagine having to shoot a gun like Sally Adee. I don’t know what ‘flow’ feels like but my thoughts became jumbled. I often daisy-chain absurd thoughts to entertain myself as I drift into sleep but this was different. I felt like I had no control over the remote.

When my session was over Fugedy sat next to me as I tried to solve the nine-dot logic problem. Last spring, a pair of Australians — Richard P Chi and Allan W Snyder — published a paper in Neuroscience Letters claiming that inhibiting the left hemisphere for 10 minutes made participants in a study 40 per cent more likely to solve a difficult task, like the nine-dot logic puzzle. I’d tried solving the infamous Google Interview Questions online but hadn’t ever attempted this one. But after 20 minutes of TDCS, I strike out. I had wicked performance anxiety and a well-meaning Fugedy patiently urging me to think outside of the box. I couldn’t help but feel that I was wasting his time.

I return to New York with my TDCS kit (the Transportation Security Administration checks it for gunpowder residue) and take my dose after my multivitamin. It’s actually a wonderful reprieve to build in a 20-minute meditation session into each afternoon, and by day three I’ve solved the logic problem. For those who don’t know, the problem goes like this: there are nine dots in a square. Three up, three across. You’re supposed to join all the dots without picking up your pen using only straight lines. You can’t use more than four straight lines. I solve it pretty quickly by cheating. I don’t look up the solution but I do draw a massive nine-dot set and fold the paper into strips and then triangles until the dots line up and I can knock them all out in one stroke. I also consider drawing the dots really small and taking a Sharpie Magnum 44 and blacking out the whole square with one line, but I decide against it. There has to be a legitimate solve.

It’s hideously narcissistic. I feel like I’ve earned the right to be smarter simply because I was curious enough to buy a plane ticket to Georgia and run a couple of drills

On the fourth day I remember Fugedy’s advice. I let my lines go wild outside of the box’s parameters and solve it by creating diagonals that hinge far outside of the corners. But here’s the thing, I don’t know if that’s attributable to Fugedy’s words or TDCS. ‘Think outside of the box’ feels like a pretty big hint.

The second week I try to stimulate the brain’s language centre but I only do it for two days. I already speak four languages and while I’d love to learn Spanish since it seems the most useful and the easiest to practice with native speakers, I know French already and the romance language cognates are too easy. So instead, I elect to learn Farsi. I’m not learning how to read and write. I’m just learning vocabulary words written out phonetically in the English alphabet. I take two quizzes before TDCS — one with 33 vocabulary words and the other with 48 — and again afterwards. I give myself two minutes to study both sets. The first quiz I get 30.3 per cent of the words wrong. After TDCS only 12.1 per cent. On the second quiz I get 35.4 per cent wrong; after, 8.3 per cent. The improvements are marked but I can’t get excited because it didn’t feel startling. I started building memory devices like I always do when I’m learning new words. The word for war in Farsi is jang which means ‘sauce’ in Korean. If I picture a battleground drenched in thick red blood I know I’ll have that word forever. It felt entirely unremarkable.

‘I shoot 25 bullets, conduct TDCS for 10 minutes, and then shoot 25 more.’ Credit Jon Snyder

Next I moved on to stimulating the motor cortex. Since Fugedy’s kit only supplied one industrial-strength elastic bandage, I use a too-tight Hello Kitty sleep mask for the anode that needs to go on top of your head and to the left. I’m relieved to be home alone. I’m going to try to learn how to twirl a pen, in a practice known in Japan as mawashi. It’s otherwise known as that annoying but enviable gift that all Asian mathletes seem to have, where they can register impatience and boredom with elegantly spinning mechanical pencils. Between that and the Hello Kitty sleep mask, I’m a study in abusing electrical neuroscience to get way more stereotypically Asian. I’ve always been jealous of pen-twirling but too cool to practise it, and the one time I tried it was really, really hard. I prepare by watching a YouTube video so that I can envision it in slo-mo. I grab a medium-point, plastic Bic Round Stic since it’s nice and long. For 10 minutes I try spinning, but no dice. I can get the twirling bit right, but I can’t catch it with my forefinger. Not even once. It repeatedly goes flying, skittering off the bed and on to the floor. I pause to reflect that I am beginning to spend a weird amount of time in bed during the day. Ten minutes into exciting the motor cortex, I catch the bastard 11 times. Back-to-back only once but the pen feels heavier. I learn how to lower my hand slightly at the right time to create a slight wave that helps the pen complete a full rotation. It’s a revelation. This feels different.

By the time you’re in your 30s, unless somebody makes the god-awful decision to gift you with a cooking class or salsa lessons, it may have been a while since you learnt something new. Since I’d only learnt how to ride a bike two months prior through a course, I can vividly recall what it feels like to learn how to do something physical. I know what it feels like to go from panicking and veering into whatever you’re looking at, to the wildly alien sensation of lifting your legs simultaneously and catching the pedals to move yourself forward in an intended direction. It’s like ice skating or learning to float. This pen business was nothing like that. It felt a great deal harder the whole time. And it was annoying to have to repeatedly pick the pen up off the floor. Amid my frustration, I start to wonder if TDCS makes you better at sex. I want to look it up but I’m pre-emptively repulsed. I’m also unnerved that this is where my brain went, even if I’m definitely not the first person to consider it.

I make an appointment with my local shooting range, making sure that the instructor’s cool with me bringing my kit, but then I start to feel guilty. In any TDCS study I’d be a healthy subject. I don’t have depression, schizophrenia, seizures, or incapacitating pain, and I don’t need stroke rehabilitation for aphasia or compromised motor skills. When Fugedy and Bikson talk about the possibility of creating a viable, available option for those people who find typical treatments ineffective, they’re stoked. They’ve witnessed stunning improvements in the quality of life for numerous patients, and regardless of how different their approaches are to the field, they’re devoted to the prospect of helping the sick. They’re both frustrated with the cockamamie way medicine works in America. And while I certainly don’t think I have the power to hinder the cause, I respect their work enough to wonder if I’m a liability to them. I know TDCS has a credibility problem, I see it every time I explain it to my friends. They’re curious, but they also think I’m nuts. When I describe all the wonderful palliative properties aloud it sounds so unlikely, even to my ears. It sounds like snake oil.

I am 33 years old and these are seriously the most terrible things I have witnessed. I am astoundingly, piggishly, lucky

It’s been less than a month and here I am, mildly surprised that I haven’t solved the stock market or learnt how to code in a fortnight. It’s hideously narcissistic. I feel like I’ve earned the right to be smarter simply because I was curious enough to buy a plane ticket to Georgia and run a couple of drills. I’d even considered buying an entire box of skinny metal pens from the Japanese stationery store to gain an edge because they’re heavier on one side and because I can batch-process picking the bastards up. Even in the fish bowl of first-world problems, feeling any of this is so extra. Griping about not TDCSing myself to genius level should extinct me on general principal, to where I’m just the smell of burned hair, a scorch streak and some smoking shoes because you know what? I am just too gross to live. This is the way that TDCS has made me feel special.

While I’m reading some message boards about the new foc.us kit, Bikson contacts me. It’s like he knows. He forwards me an email (with the identifying portions redacted) from a guy with bipolar disorder II who is using TDCS with a machine like mine to treat his condition as he has become allergic to his antipsychotics. The whole thing bums him out. ‘When people are ill and don’t get the best possible care, is anyone culpable?’ he writes. ‘And what does this mean for real TDCS?’ In the letter the guy describes his history with mental illness and how it’s affected his work and personal life. He explains that he’s tried other drugs (he dabbles with noortropics but finds the costs prohibitive) and then cites a TDCS study on depression and another on seizures and arrives at the conclusion that the seizure suppression montage would help his mood swings. He claims success, but he also talks about alterations in his sleep patterns and accidentally ‘changing perception’ while he’s ‘hacking around’.

The desperation in the guy’s email makes me feel ill. I pan out for a little perspective and try to recount the worst things I’ve experienced — ever — and the only life events I can come up with are break-ups. Two were awful. For one I couldn’t get out of bed for a week and all I did was smoke cartons of Parliament Lights and eat tortilla chips until my hair smelled so bad it made me gag. There was a third break-up but that one had been excised so cleanly from my brain that it was like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. I am 33 years old and these are seriously the most terrible things I have witnessed. I am astoundingly, piggishly, lucky, and yet here I am soaking up all this TDCS equipment and expertise out of sheer curiosity.

I finally make it to the shooting range the next week. It’s in the basement of a building in a central business district and you’d never guess it was there. It feels like a clubhouse. There’s an office area, a designated place where people clean their guns, a classroom and a set of tables with benches. It’s a place where cops hang out and there’s free coffee. I have a semi-automatic 22. It’s a rifle, because I need a licence to shoot anything else in New York.

I take a safety class; I learn how to load and how to jam the butt of the gun into my shoulder, to hold it in place and to anchor my elbow into my torso to steady it. I learn that my right is my dominant eye. I also learn how to match up the gold dot into the little notched groove for front and rear sight alignment. You have to breath a certain way and you have to allow the target in the back to get all fuzzy and ‘bokeh’ and be chill.

I shoot 25 bullets, conduct TDCS for 10 minutes, and then shoot 25 more. The first time, I hit the bull’s eye 24 times. With TDCS, I hit 25. The grouping suggests that my gun’s sight picture is slightly off. I feel like I may have sensed it, but I kept going anyway, blasting and reloading the Ruger, shells pinging off the white plywood partitions. I wonder why I didn’t stop to make the correction. Maybe I dropped into flow state — I can’t be sure. I wish I had an app that could tell me.