wikipedia

In 1946, the French philologist André Dupont-Sommer published the first Jewish tombstone inscription from Firozkoh in Afghanistan. Dated between the 11th and 13th centuries, when the city was destroyed by the invading Mongols, the tombstone inscriptions follow a standard pattern. Chiselled into the rock with unadorned lines and no decoration, they mention the name of the deceased, the date, conventional tributes such as ‘blessed in the Garden of Eden’ and ‘God fearing’, and an appropriate biblical quote.

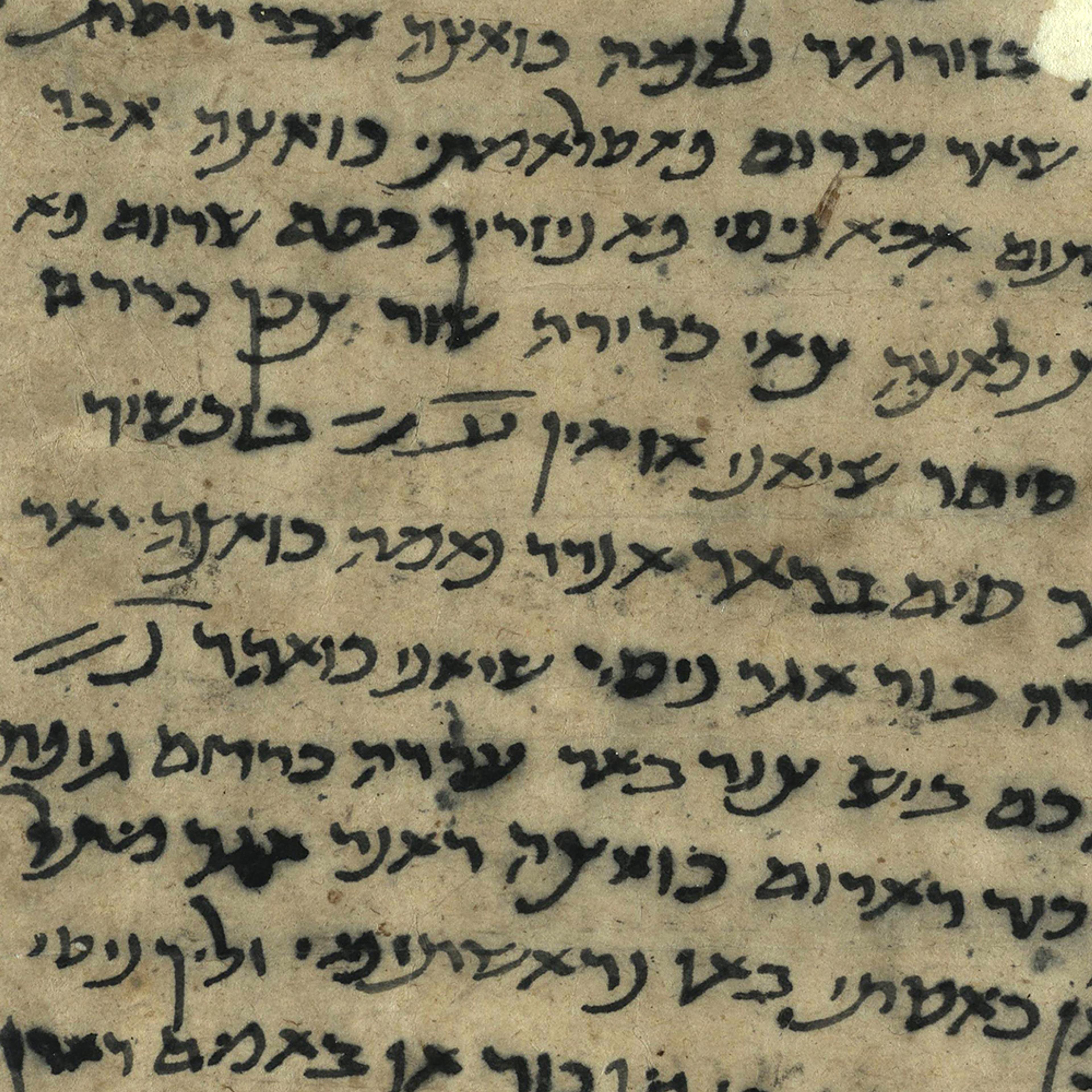

For all their simplicity, until recently these epitaphs were one of the few sources for Jewish history in medieval Afghanistan. Scholars studied the mixed Hebrew and Persian names, the aesthetics and, most importantly, the language. Like Jewish communities throughout today’s Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia and western China, Jews in Firozkoh spoke and wrote Judeo-Persian, a Jewish language, like Yiddish, that is intelligible to standard Persian speakers but incorporates Hebrew vocabulary and is written in the Hebrew script.

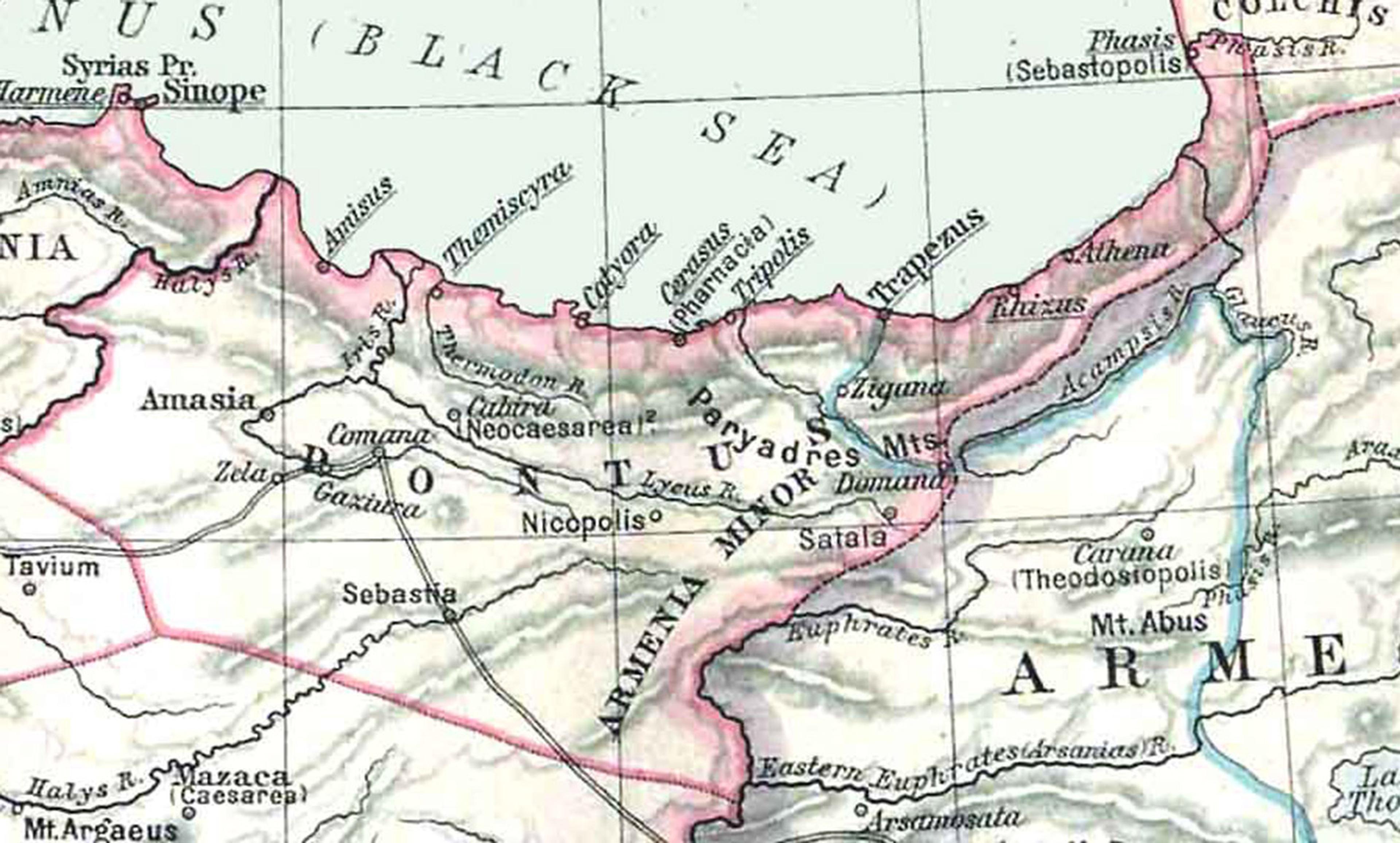

The graves offer a tantalising glimpse into a largely unknown Jewish community. They raise many questions. How did Jews live on the eastern boundaries of the Islamic world? What did they do? Where did they come from? The short epitaphs, along with a few other inscriptions and scattered references in histories and literary sources, could only tell so much.

Such questions about the history of Afghan Jews were the reason a 2011 television report on Israel’s Channel 2 news set the scholarly community abuzz. The report was quickly picked up by the world media and described how, a few months earlier, foxes scratching in the dirt revealed a hidden cave, somewhere in the Afghan province of Samangan. Inside the cave, so the story goes, local villagers found a trove of Jewish documents nearly a millennium old. The find is now known as the Afghan Geniza.

The truth is that we will likely never know where or how the find came to light, though other manuscripts have been found in the same arid region. Smuggled out of Afghanistan and held by a shadowy network of antiquities dealers, the vast majority of the corpus’s hundreds of pages remain unpublished and unavailable for research. However, 29 manuscripts, bought by the National Library of Israel in 2013, shed new light on this discovery (full disclosure: I work at the library, but in a different department).

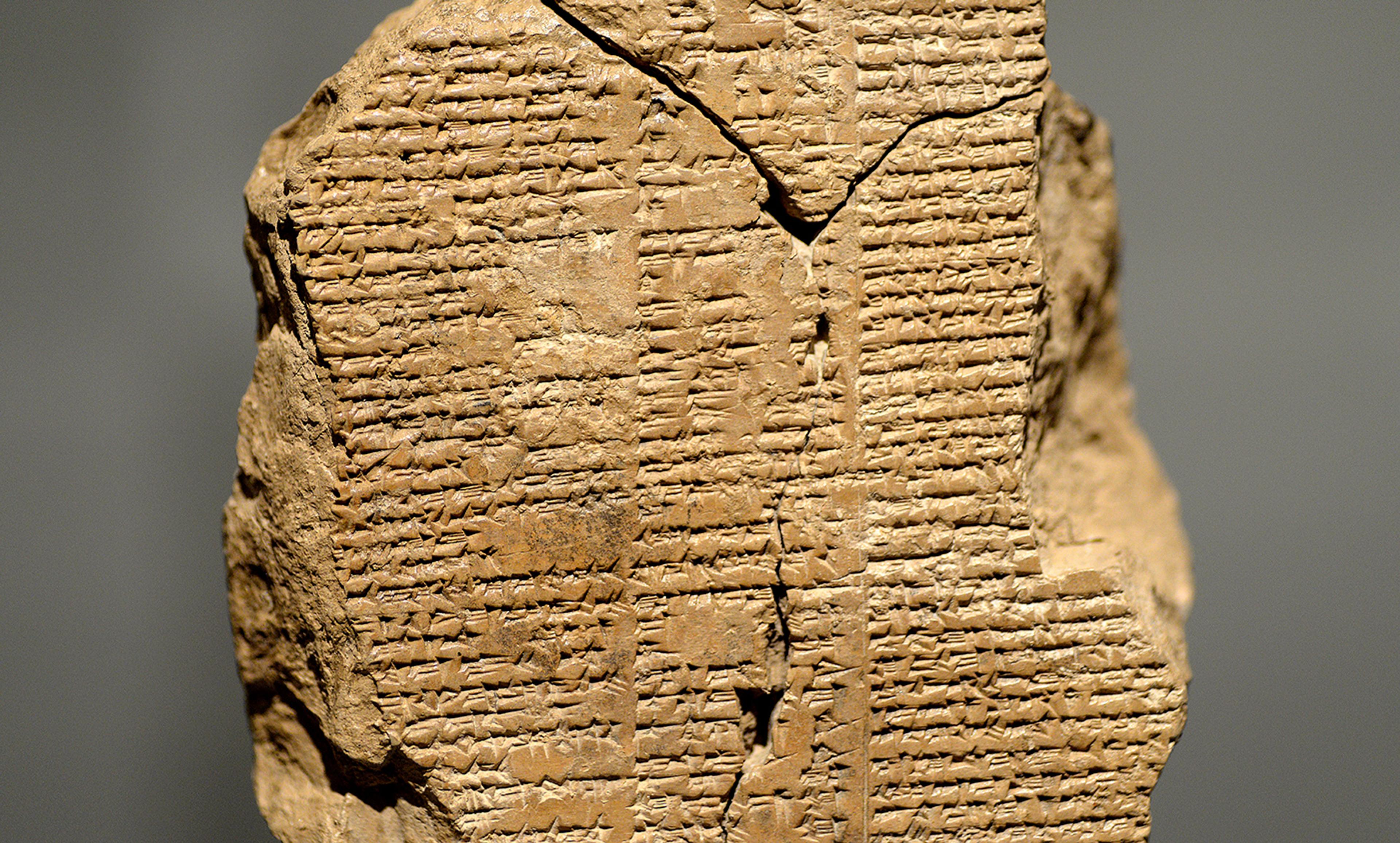

Like its namesake the Cairo Geniza – the trove of discarded books and papers kept in the ‘genizah’ (Hebrew for storeroom) of the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo – the manuscripts from Afghanistan are a grab-bag of texts. There are legal documents in standard Persian, written in Arabic script; personal and business letters in standard Persian, and more in Judeo-Persian; fragments of Persian poetry; a commercial document in Arabic; and, most spectacularly so far, a page from a commentary on the biblical book of Isaiah by Saadia Gaon, the 10th-century Jewish philosopher.

The manuscripts are likely part of a family archive belonging to Jewish merchants from Bamiyan, an important trading city on the medieval Silk Road. Most of the legal documents are receipts of debts owed to the family patriarch Abu Nassar Yehuda ben Daniel. The letters also concern Abu Nassar and his son Abu al-Hassan Siman Tov’s tax obligations, land purchases and commercial dealings. The legal documents follow Islamic law, and Muslim names appear throughout. Abu Nassar’s business and life were clearly not confined to the Jewish community.

One of the Judeo-Persian personal letters, sent from Yair ben Emed (apparently, Abu Nassar’s son-in-law) to Abu al-Hassan, paints an intimate picture of family dynamics. Yair pleads with his brother-in-law that, as much as he might like to move to Bamiyan from Ghazni, the city nearly 100 miles away from where he lived, his economic circumstances made it impossible. ‘I am not acquainted with any other profession, and I am not a man [who is accustomed] to travelling and to being remote from home,’ he writes. ‘And you know that [in] this business and work that I do, if I am absent from the shop for one day, I will be without profit that day.’

The Judeo-Persian of these letters is not only important because it was spoken by the region’s Jews. Judeo-Persian also preserves antiquated vocabulary and grammatical forms lost from standard Persian. The Afghan Geniza’s medieval Judeo-Persian will help scholars understand the development of Persian as a whole. Previously, the corpus of Judeo-Persian texts from the eastern reaches of the Iranian world consisted of two letters and a handful of literary and religious works.

While Arabic continued to be the predominant legal language in the region, the inclusion of Gaon’s Judeo-Arabic commentary implies that Abu Nassar’s family had a deeper knowledge of the language. It might indicate that the family – and, perhaps, other Jews – had emigrated from Baghdad or other Arabic-speaking regions to the west of Bamiyan. Such movement was common; Judeo-Persian documents found in the Cairo Geniza show that Persian-speaking traders had moved there from points east.

But language is not the only historical clue that the Afghan Geniza provides. The documents include a wealth of details, including names, occupations, prices, weights and measures, foodstuffs, and more. Historians have used such information from the Cairo Geniza to reconstruct the economic and social history of a network of Jewish traders that stretched from Morocco to the Malabar Coast in India.

This painstaking work on the Cairo Geniza proved crucial to understanding medieval Islamic society at large, and not only its Jewish component. This was possible because Jews were so thoroughly integrated into the commercial structure of the Muslim-majority society. The insights gained from the geniza documents about Jews’ involvement in trade, industry, finance, and the legal system, could, on those grounds, be applied to the general population, too.

The same observation no doubt holds true for the Afghan Geniza; the documents show Abu Nassar’s close contacts with local Muslim communities. But as Shaul Shaked, professor emeritus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, cautions, 29 manuscripts lack the context and volume of data that hundreds could provide. As he put it, until the entire find is available for research, the Afghan Geniza ‘offers more questions than answers’.