Courtesy Dr Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP (Glasg). /Wikimedia

You would think that amid all the human carnage in the Middle East, the destruction of archaeological sites hardly counts for much. But the smashing of the Mosul Museum by the self-styled Islamic State, and their blowing up of a succession of high-profile ancient cities last year – Nimrud and Hatra in Iraq, Palmyra in Syria – have grabbed more media attention than their wholesale butchering of men, women and children.

There is something about the deliberate annihilation of cultural heritage that strikes a deep blow against the identity of human beings, collective and individual. When a madman attacked Michelangelo’s Pietà at the Vatican in 1972 and broke off the Virgin Mary’s arm, public outrage far exceeded the offence taken at the mass amputation of living hands in repressive Middle Eastern courts of law. Ancient works of art and historical monuments symbolise the endurance of human achievements. Perhaps that is why their loss seems to some more shocking than the destruction of lives that only briefly inhabit time and space.

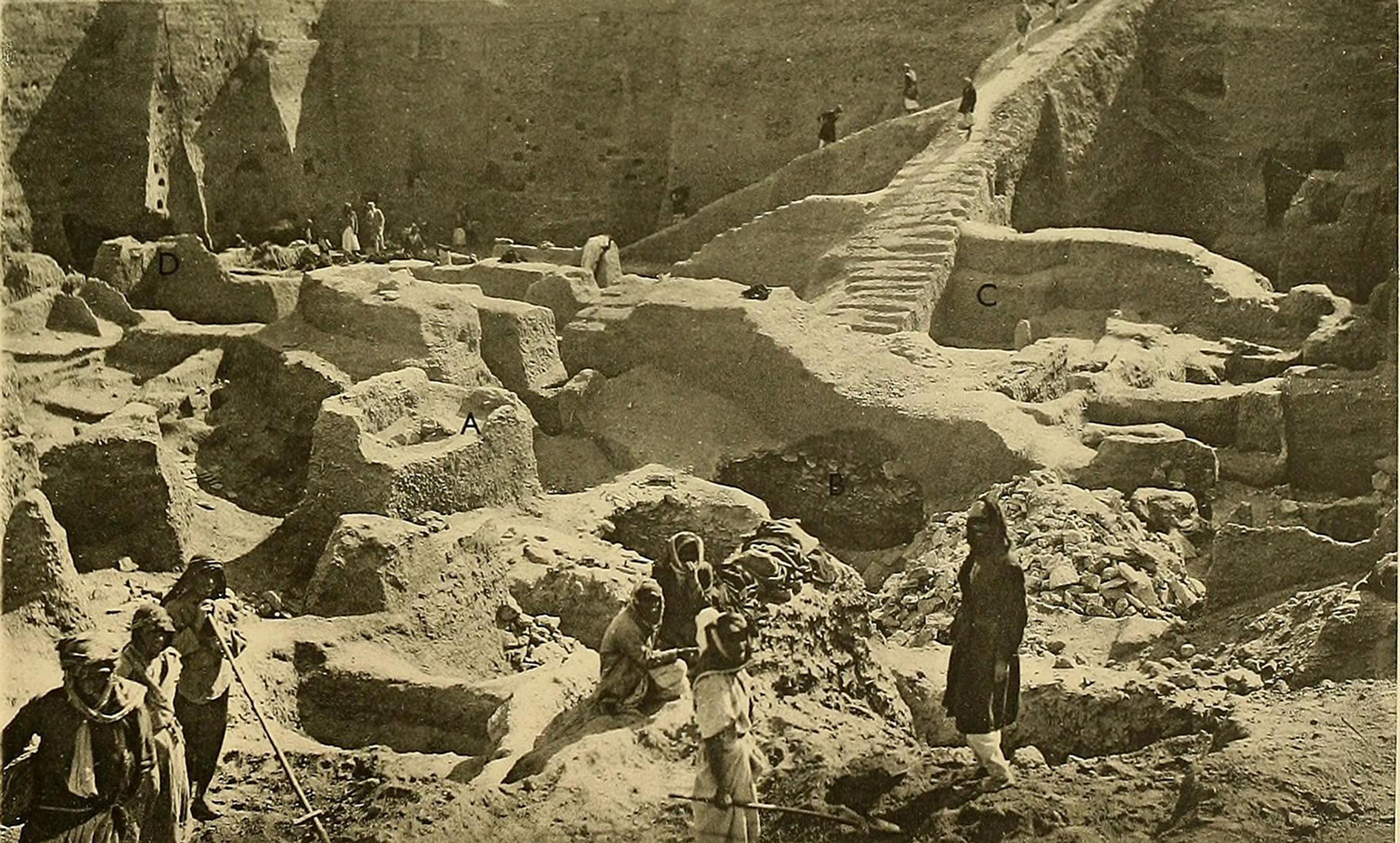

The destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East is not an innovation of the Islamic State. Since Saddam Hussein lost control of southern Iraq after his army’s expulsion from Kuwait in 1991, there has been a concerted effort to loot dozens of archaeological sites in what is the cradle of urban civilisation. The harsh conditions of life, first under international sanctions, and then during the break-up of the Iraqi state since 2003, encouraged local people to seek treasure in the ground beneath their feet. The illegal trade in Mesopotamian antiquities that was viciously repressed by the Ba’ath government sprang back to life and continues to this day. It has brought on to the market many thousands of small objects. Their exact archaeological provenance can only be guessed at, and they are now dispersed among museums and private collections worldwide. For archaeologists, the destruction of ancient sites by looting is just as terrible to learn of as the smashing of sculpture in Mosul and the detonation of high explosives in Palmyra. But it is not all bad news: out of the destruction and looting, and partly because of it, emerge striking gains in knowledge of our oldest literary inheritance.

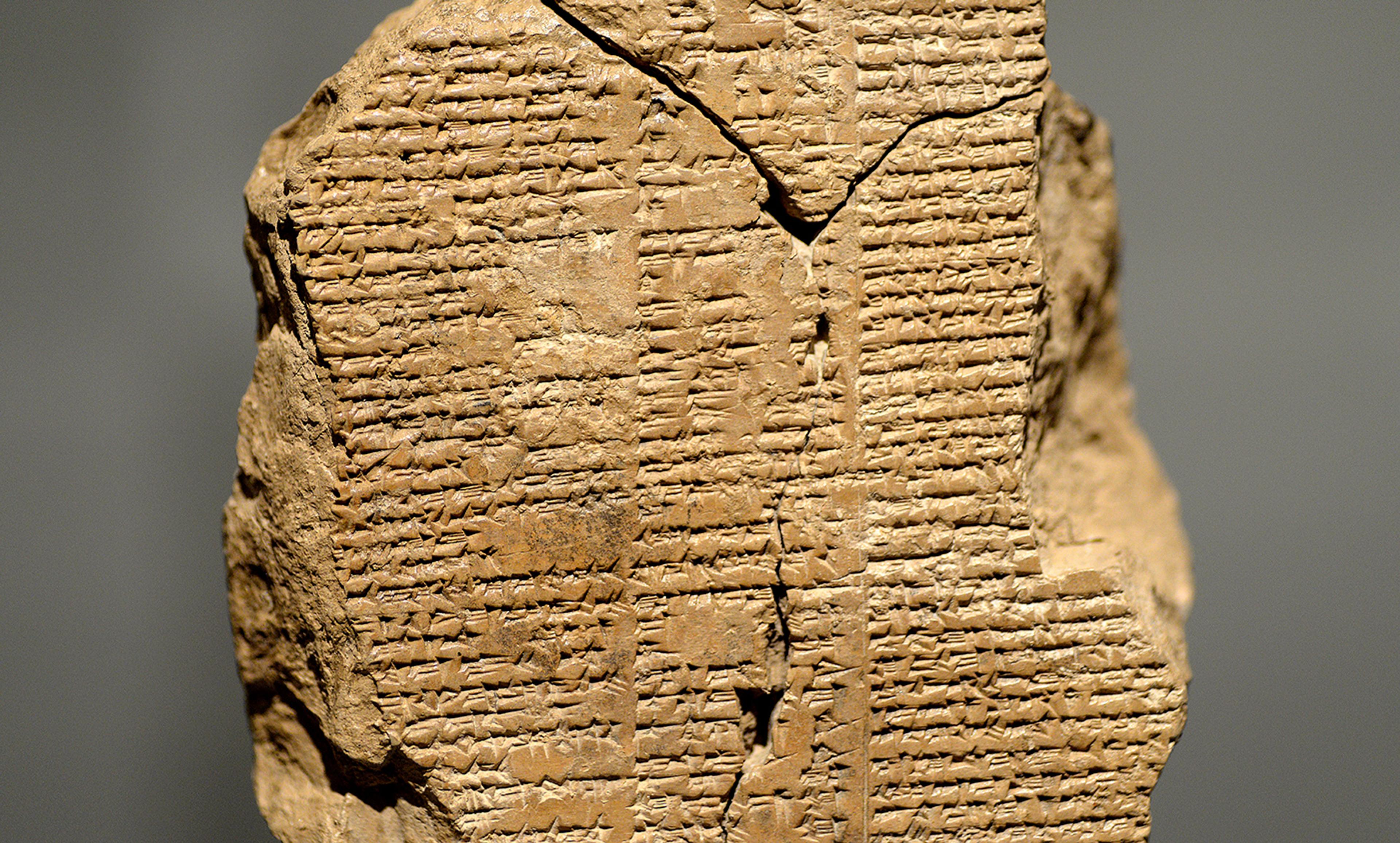

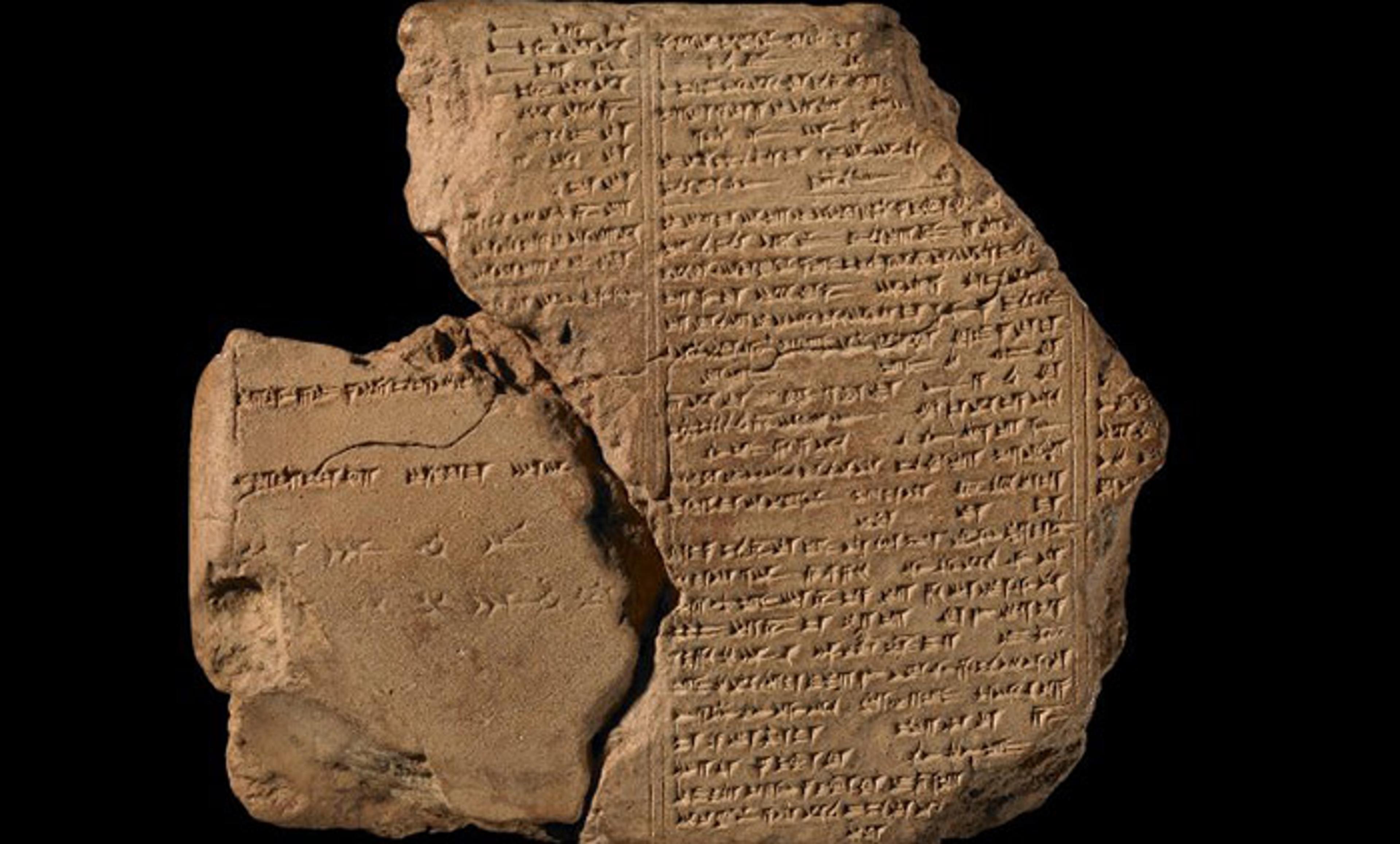

Among the objects that passed through the antiquities’ markets in the past 25 years are large numbers of clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform. These are documents that bear witness to every aspect of life in ancient Mesopotamia – public, political, religious, spiritual, literary, legal, economic and administrative – across 3,000 years of ancient history. Because cuneiform tablets contain written texts, their writing, spelling and content often reveal how old they are and where they come from. Assyriologists (historians of Mesopotamia) use them to reconstruct in astonishing detail the history, culture and science of the Near East before Alexander the Great.

The recovery since the 1860s of the written culture of ancient Mesopotamia has been one of the least noticed but most noteworthy feats of scholarship of modern times. The world’s most ancient literatures, 4,000 years old and lost for nearly half that time, are now in the process of recovery from broken cuneiform tablets scattered around the world.

From the very beginning, one text, above all others, emerged as the finest representative of this literature: the Epic of Gilgamesh. This Babylonian poem, reconstructed from more than 200 fragments, tells the story of one man’s doomed quest for immortality. It struggles with the same existential preoccupations as we do: what it means to be mortal in an eternal world, how human nature differs from animal and divine, the ethics of political power and military force. It reflects ourselves, for we are all Gilgamesh, and therein lies its power to move us.

Gilgamesh continues to spring surprises by proving to us that ideas we think modern are not modern at all. In 2011, Farouk Al-Rawi, an Iraqi Assyriologist now living in Britain, was shown a group of cuneiform tablets by an antiquities dealer in the Kurdish part of Iraq. He spotted among them a large, unusually shaped fragment and urged the Sulaymaniyah Museum to acquire the whole group. Sitting down to clean the strange piece and embark on deciphering its text, he realised that he was looking at a piece of the Epic of Gilgamesh. In November 2012, he and I spent four days establishing a definitive decipherment, and the results were published in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies two years later.

Assyriology customarily hides its light under a bushel, and there was no press release. It was a further 10 months, in October last year, before the media realised what we had done and signalled the discovery to non-specialists and the general public. Downloads of the academic paper climbed briefly from a handful per month to 150 per day: not exactly big-league, but impressive for an obscure article in a learned journal of tiny circulation.

The newly discovered fragment comes from an episode in which Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu invade the distant Cedar Forest to kill the ogre who guards it for the gods, and to plunder its timber. The text of the epic is quite stable – meaning that different manuscripts hold pretty much the same text – but some lines are beset by damage and others are missing altogether. The new piece fills a large gap in the poem at the beginning of the episode, when the two heroes approach the Cedar Forest and stand awestruck in its deepening shade. There is a lively description of the deafening noise that filled the forest canopy: the squawks of birds, buzz of insects and yells of monkeys form a cacophonous symphony to entertain the forest’s guardian.

This is not the familiar forest of northern folklore, of Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel: it is a jungle, a Heart of Darkness presenting the same moral dilemmas as Joseph Conrad’s novella. Is it right for the forces of civilisation to invade, kill the guardian and steal his timber? The end of the episode makes clear the poem’s ambivalence to the destruction of the forest. ‘My friend,’ says Enkidu to Gilgamesh, ‘we have reduced the forest to a wasteland; how shall we answer our gods at home?’ The pillaging of nature was not without shame, even then.

The Epic of Gilgamesh asserts the endurance of civilised values in the face of barbarity. It is an ancient monument like Nimrud, Hatra and Palmyra, but its substance is words and ideas, and so it cannot be destroyed like material things. And it is not yet complete. More tablets like the one in Sulaymaniyah will come to the surface, either on the market or through regular excavations. Then, on some distant future day, we will have finally reconstructed this most majestic Babylonian poem. All that is needed is committed Assyriologists, and the will of liberal society to sustain and perpetuate this tiny academic field that still has so much to teach about our human condition.