Dave Nakayama/Flickr

Artificial food. That’s what humans eat. I say this to anyone who will listen. ‘Oh yes,’ comes the reply. ‘The more’s the pity. Cheap, nasty, imitation food-like substances. It’s high time to return to natural food.’ But, no, I mean artificial in its original sense of man-made, produced by humans, artfully created.

Our distant ancestors found little good in the food that nature provided. Greens had too few calories to sustain life, chewy meat came tightly wrapped in awkward-sized packages known as living animals, nuts were bitter or oily, roots tended to be poisonous, and grains were tiny and so hard that they passed undigested through the system. Acquiring and digesting food was a constant struggle.

So sometime in the distant past, at least 20,000 years ago and probably much more, members of our species decided they could improve on nature. They discovered how to process raw foods by using fire to cook them, or stones to chop and grind them, or coopting microorganisms to ferment them. They began creating niches for the more edible species, breeding sweeter fruits, less toxic roots, and bigger grains. In short, they created the art of cookery to transform the natural.

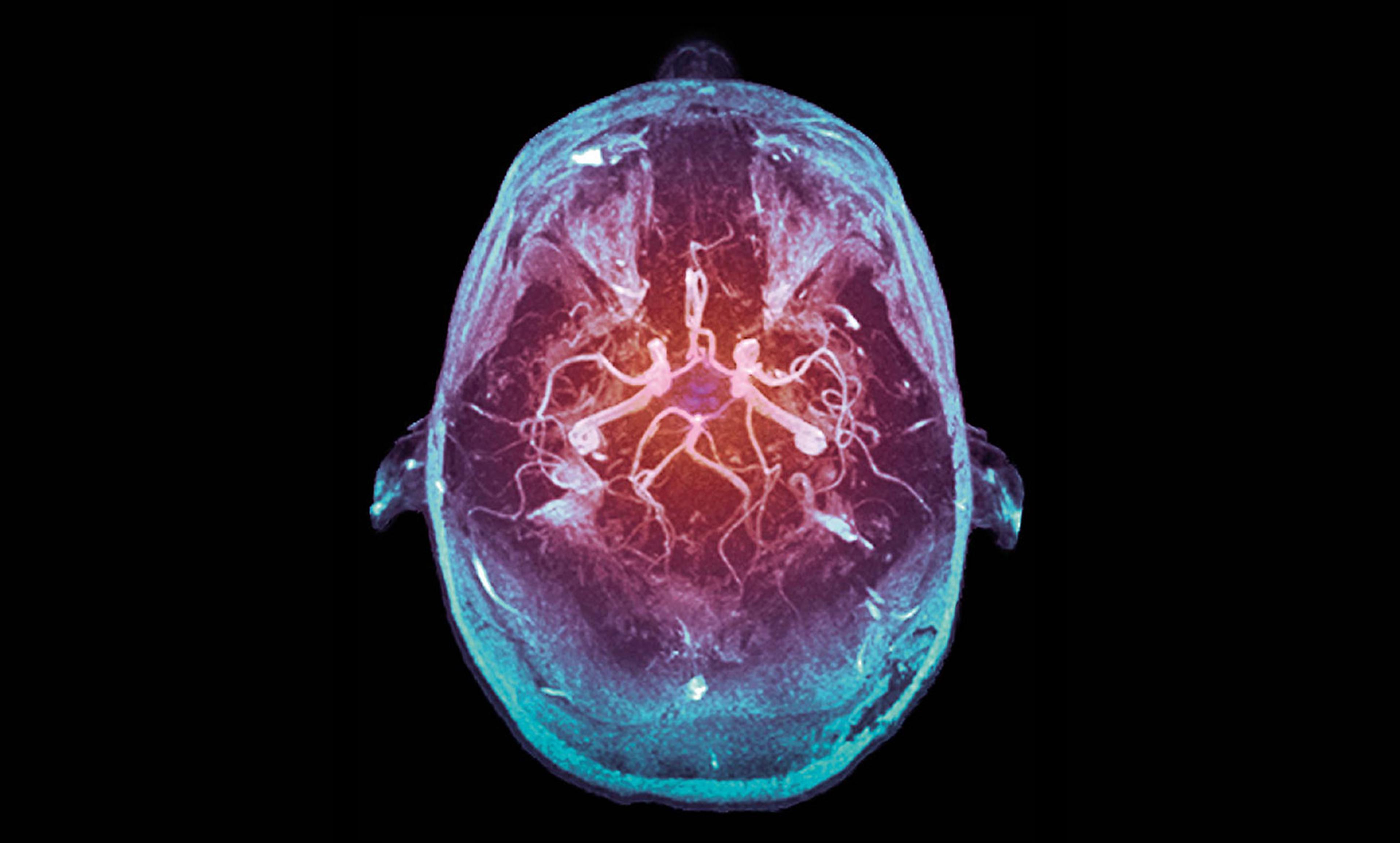

The art of cookery, they believed – and modern science has confirmed – produced more food that, on balance, was nutritious, easier to digest, safer, longer-lasting and better-tasting than raw plants and meat. With the benefit of hindsight, anthropologists such as Richard Wrangham at Harvard have argued that bodies changed as the energy formerly spent on digesting was diverted to brains that increased in size, and society evolved as a response to cooked, and hence communal, meals.

Over the millennia, humans continued to improve unpromising raw materials. Tough little barley grains, they discovered, after sprouting, drying, grinding and fermenting, made delicious beer that eased pain and induced merriment, besides providing calories and nutrients. Dull, flatulent soy beans, after soaking, crushing, fermenting and pressing under carefully controlled conditions, yielded a nutritious condiment that enlivened the simplest meals. And cacao beans, after equally arduous multi-stage processing, ended up as appealing chocolate.

Not one of these products bore the least resemblance to the original raw material. Far from being second-rate imitations of the natural, they were new creations, works of artifice and genius. In this, the new foods were no different than garments created of silk or wool, or buildings constructed from wood, stone or bricks. Why it is so little recognised that food is as much a human construction as clothing or housing is hard to say. No one advocates returning to ‘natural’ housing. What would that be, a shelter under an overhanging cliff? Perhaps it’s because the term food is so capacious, or better, imprecise, covering everything from farm products such as wheat to prepared dishes on the table. By contrast, terms such as clothing and housing are never used for cotton bolls or timber.

The trade-off for improved foods was hard, daily work. With human, animal, wind or water the only power available, with organic materials the only fuel, the range of attractive, nutritious edibles expanded only thanks to the labour of the majority who processed and cooked. Only a tiny proportion of the population had the luxury of doing other things with their lives, such as governing, fighting, praying and thinking, than processing and cooking food.

In just the past two centuries, across ever greater areas of the world, fossil fuels replaced wood, water or other more traditional power sources. Steam engines and then electricity powered flourmills, refrigeration plants, breweries and canneries. Women no longer spent much of the day scouring for brush, dung or wood, but had heat to cook with at the turn of a knob. Industrially processed food – that is, food prepared using convenient and powerful fossil fuels – had arrived.

The benefits to health and to society came swiftly. Canned and frozen fruits and vegetables in winter eliminated the scurvy that had plagued the northern United States. Iodized salt did away with the goiter belt of the Midwest. More nutritious, safer food contributed to a taller population that lived longer. Life expectancy increased from under 50 years in 1900 to around 75 at the end of the 20th century. Freed up from laborious food processing, people, particularly women, flocked into new occupations. Everyone could now enjoy the dignity of eating the white bread and red meat formerly available only to the privileged.

Life being what it is, these advances also brought risks. If deficiency diseases have disappeared, new, dangerous types of e-coli bacteria can spread quickly through food that is prepared in large facilities. If longevity has increased, so have the diseases associated with abundant food, such as diabetes and heart conditions. It’s not surprising that, without historical perspective, activists hope that poor societies will continue to process their foods by hand. Nor is it to be wondered at that concerned citizens urge their fellows to avoid processed food, argue that things have gone too far, and advocate a return to some point in the past.

Yet yearning for some ideal past, as this brief sketch shows, overlooks the fact that more people are better fed on tasty, safe and nutritious food, as well as having more opportunities in life, all thanks to food processing. To point the finger at certain processed foods and call them ‘bad’ misses the point that with food, as with medicine, it’s all in the dose. Living on potato chips and packaged cakes is not a good idea. Enjoying them occasionally is just fine.

We are not and, unlike animals, have never been stuck with what nature provides. And our choices have never been wider than they are at present. For those who don’t want potato chips and snack cakes, food processing is supplying a wealth of alternatives. Organic foods? Whole aisles in the supermarket. Gluten-free, vegan or paleo? The local hypermarket has everything needed, ready to be put on the table with minimum labour and without breaking the budget. As new needs and wants appear, the art of cookery at once expands to satisfy them, as nature never could. That’s why it’s a cause for celebration that food is something we make, something we process, something not natural, but artificial. It’s to everyone’s benefit.