Untitled. Possibly relating to the fair in Albany, Vermont. Courtesy Library of Congress

Most of us know and value pleasant experiences. We savour the taste of a freshly picked strawberry. We laugh more than an event warrants, just because laughing feels good. We might argue about the degree to which such pleasant experiences are valuable, and the extent to which they ought to shape our lives, but we can’t deny their value.

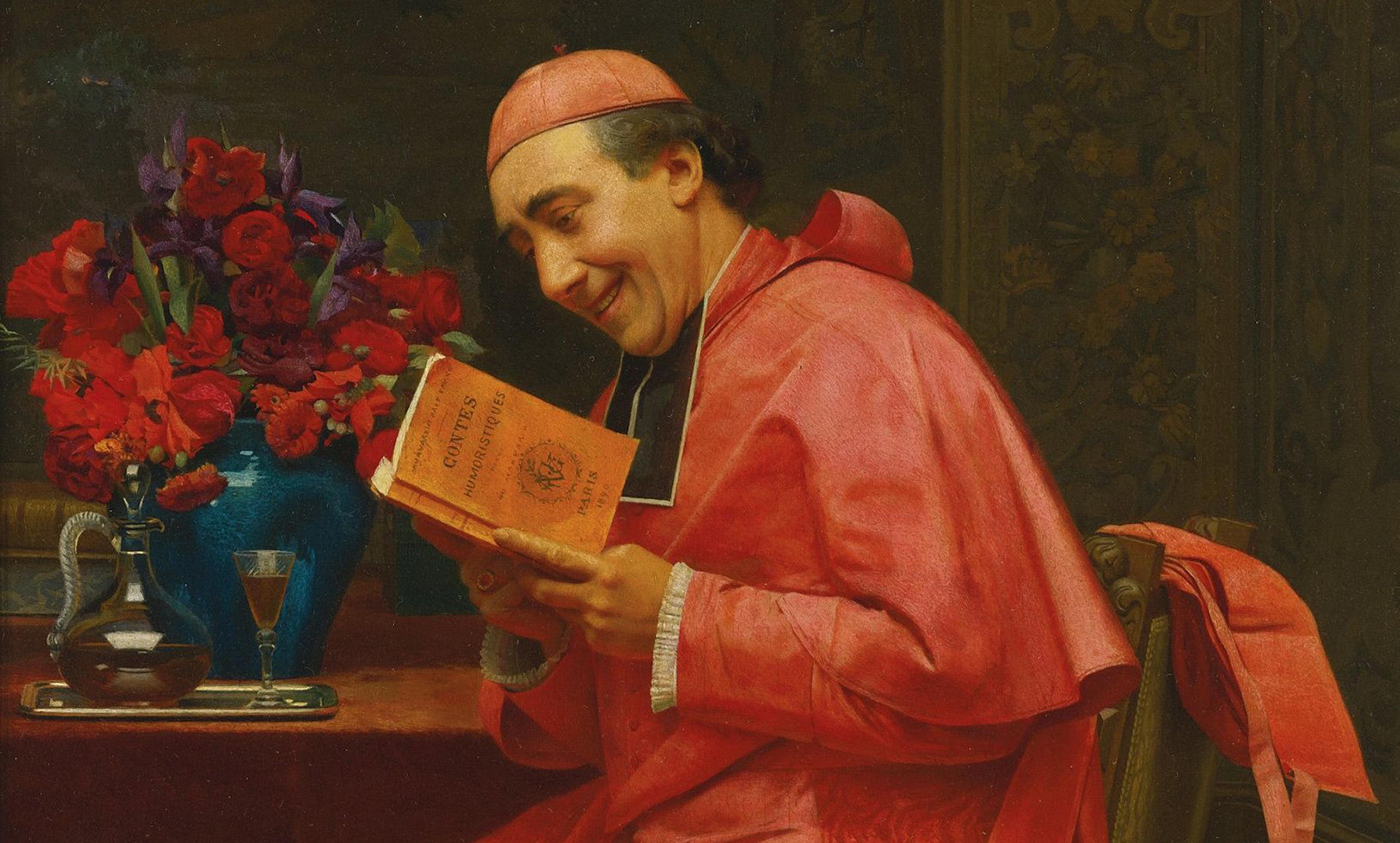

So pleasant experiences are necessarily valuable, but are there also valuable experiences that are not necessarily pleasant? It seems there are. Often, we have experiences that captivate us, that we cherish even though they are not entirely pleasant. We read a novel that leads us to feel both horror and awe. We binge-watch a TV show that explores the shocking course of moral corruption of someone who could be your neighbour, friend, even your spouse. The experience is both painful and horrifying, but we can’t turn it off.

These experiences seem intuitively valuable in the same way that pleasant experiences are intuitively valuable. But they are not valuable because they are pleasant – rather, they are valuable by virtue of being interesting.

What does it mean for an experience to be interesting? First, to say that something is interesting is to describe what the experience feels like to the person undergoing it. This is the phenomenological quality of the experience. When we study the phenomenology of something, we examine what it feels like, from the inside, to experience that thing. For instance, most of us would describe eating our favourite foods as a pleasurable experience: the food itself isn’t pleasurable, but the experience of eating it is. Similarly, when we talk about something being beautiful or awe-inspiring, we aren’t describing the thing itself, but rather our experience of it. We see the sunset and feel moved by it; the beauty is something we experience. Likewise the awe it inspires is a feature of our experiential reaction to it. The interesting is just like this. It is a feature of our experiential reaction, of our engagement.

We don’t always use the word ‘interesting’ in this way. In ordinary language, we often describe the objects of experience as interesting. We talk about interesting books, interesting people, and so on. When we say that a book is interesting, we more likely mean that the experience of reading the book is interesting. It just doesn’t make sense to describe a book to be objectively interesting, independently of people experiencing it as interesting. How could a book be interesting without being read? And if a book is objectively interesting, shouldn’t we all find it interesting? We don’t all find the same things to be interesting. It is a common experience for something to be interesting to one person, yet not another. So while we might describe objects as interesting, we should recognise that this is a loose, and shorthand, way to describe what’s really interesting – our experience of them.

Another way in which we use the word ‘interesting’ is in the context of describing what a person is interested in: John is interested in Second World War novels, for example. This usage also differs from what I’m describing as the ‘interesting’. It describes a particular fit between one’s interests and the objects of one’s experiences. But notice that fitting with your interests, and being interested in something, is actually a different experience to finding something interesting. We’ve all been interested in things that turn out to be boring, and we’ve all found experiences interesting when we had no prior interest in them. The interesting is thus not an objective feature of an object, nor an experience that necessarily aligns or follows from your interests. It is rather a feature of our experiences.

To say that something is interesting is also to describe a particular kind of synthesis that arises within the experience. Whenever we engage in an activity, we bring to that experience some combination of expectations, likes/desires, beliefs, curiosity, and so forth. This package contributes to the activity delivering a particular subjective experience. There is a synthesis, specific to the individual’s engagement, that determines what her experience feels like – its phenomenological quality. It is within this synthesis that a person finds an experience interesting, or not. There is no one synthesis that makes an experience interesting. Sometimes, a clash of expectations and reality makes something interesting, sometimes someone’s curiosity allows one to notice features that make an activity interesting, and so on. Because the interesting lies within a synthesis between the individual and an activity, one individual can find something interesting (say, reading philosophy) that another person doesn’t.

The synthesis is complex, unique to the subject and the experience – and, in the end, unspecifiable. This is why we tend to overlook the interesting as a valuable feature of our experiences. Pleasure, by contrast, is a fairly uniform feature of experience. We know exactly what others are talking about when they talk about pleasurable experiences, and can relate to that experience in a personal way – even if it is something that we have not experienced as pleasurable. Our reactions to the experiences that others find interesting are often different. John finds reading Second World War novels to be an ongoing source of interest, yet Julia can’t imagine a more boring way of spending her time, and can’t understand how anyone would find them interesting. In such scenarios, we are more likely to discredit the value of John’s experience than to try to understand and appreciate it. Because the interesting is by nature a more complicated, harder-to-reach, harder-to-describe feature than others, we rarely stop to think about just what the interesting is.

While wrapping our head around the interesting might be challenging, it is important to acknowledge the value intrinsic to interesting experiences. Recognising it as valuable validates those who choose to pursue the interesting, and also opens up a new dimension of value that can enrich our lives. Most of us know there is more to life than pleasure, yet it is all too easy to choose our experiences for the sake of pleasure. For many of us, though, interesting experiences are more rewarding than pleasurable experiences, insofar as their intrinsic value is a product of multifaceted aspects of our engagement. Interesting experiences spark the mind in a way that stimulates and lingers. They can also be easy to come by – sometimes just a sense of curiosity is needed to make an activity interesting. Look around, feel the pull, and cherish the interesting.