Terry Farrell’s Comyn Ching redevelopment near Covent Garden, London. Photo by Valentino Danilo Matteis

The overwhelming problem in contemporary architectural culture is that most of the critical talk about it fails to relate to the buildings that we all see every day. How can we talk about that clumsy new apartment block nearby in terms of the great movements in architectural history? Only with great difficulty. And the reason is that a few outmoded ideas alone, most of them originating in the mid-20th century or much earlier, still dominate the critical press. Buildings have to be exciting, progressive, mould-breaking to be worth discussing. Yes, there are buildings like that, and people are rightly moved by them. But as a measure for judging the great run of buildings that are erected daily – that are perhaps less than thrilling – we have no adequate way of sharing the pleasures or disappointments that they bring.

Architects tend to imitate the language of their clients and critics because they themselves are visual, visceral people for whom the thing itself and not a description of it is the dominant motivator. It has always been like that: the architects of the gothic revival spoke passionately in terms of morality and truth because that was the terminology the church-builders who employed them wanted to hear. And that has never subsided: buildings are still ‘good’ or ‘bad’, or ‘honest’ or ‘pastiche’. And ‘bad’ buildings are somehow morally ‘wrong’, and their architects lesser people because of it. This – and the whole business of delivering one-line judgments – is early Victorian language, and these terms are completely useless when applied to most buildings.

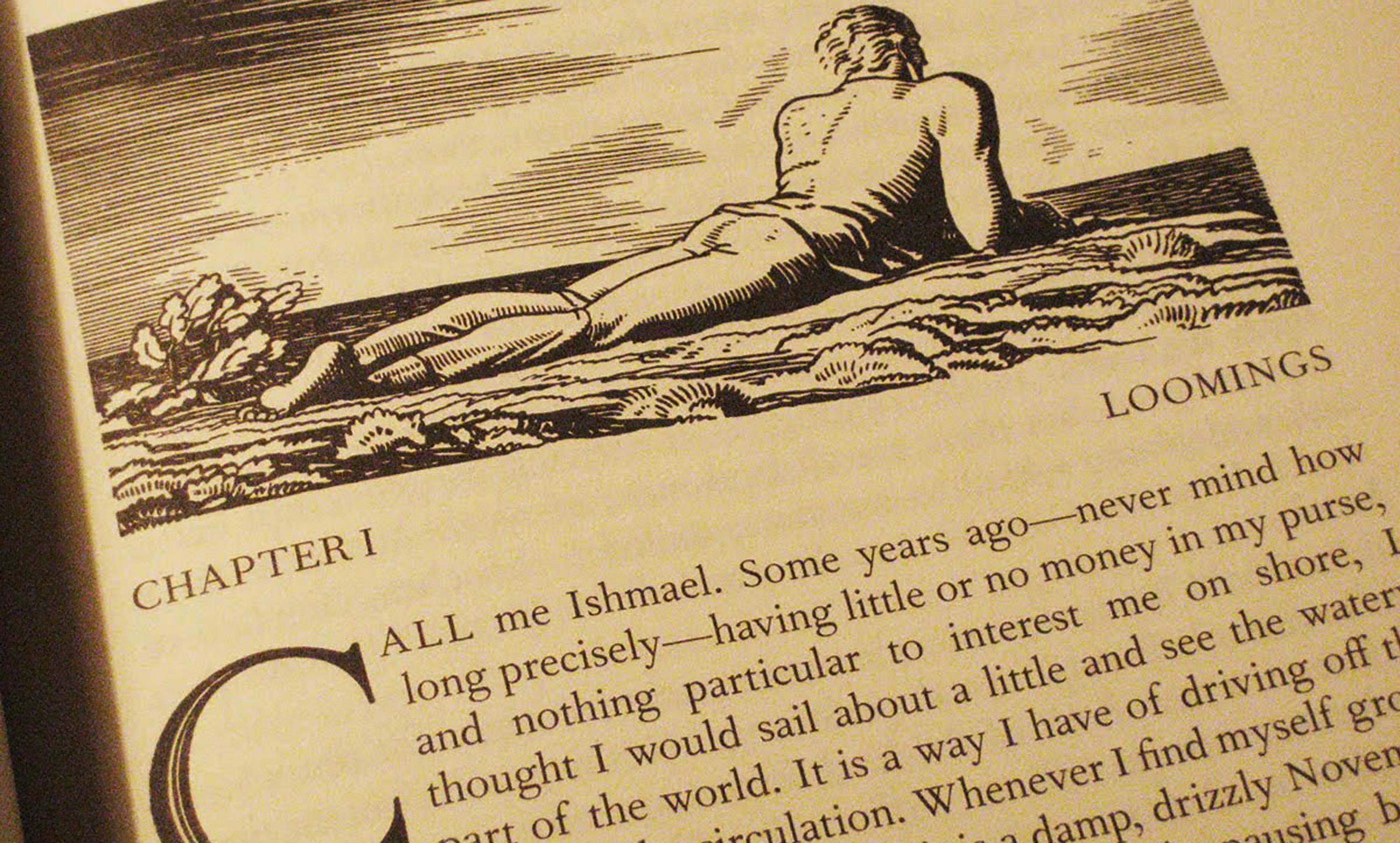

Architects, in fact, have something to learn from novelists, and perhaps especially writers of stories for children, who are adept at describing buildings in ways that relate closely to real life. Rather than presenting them in terms of ‘concepts’ – such a mid-century way of doing things! – they often offer glimpses into the character of places through vignettes: an entrance way, a hall, a room, a view. They leave the rest to the imagination of the reader, just as listeners to the best radio dramas develop the characters mostly in their own heads.

That approach can be applied to architectural criticism and history. The lesson is this: abandon the idea that there is one way of describing a building and instead draw on the many sources that we use to evaluate culture generally to give a building its due respect. For the great novelists, a building does not play a single role – it has a number of different aspects that each reflect the story and the span of the narrative. When I first discovered the French novelist Honoré de Balzac, I was struck by the way he uses highly accurate descriptions of houses in his stories as both settings and symbols. There is a satisfying interaction between the characters and the grand or shabby rooms in which they find themselves, or the places they seek out; in both Eugénie Grandet (1833), and especially Père Goriot (1835) with its large cast of characters, you feel it in the roles of the spaces and even through the arrangement of the furniture. It was no surprise to me that these novels were written just as architecture was about to undergo a massive revolution.

Most people experience buildings in precisely this ‘vignette’ form, coming and going past or through them and seeing them briefly at different angles and in varying but specific circumstances. This means that you are looking at a real thing – a door, a window, a wall, a detail of some kind; you are not looking at an ‘idea’. The question is how to tell these stories together in a coherent way. British postmodernist architecture and the way in which it was received in the 1980s show very clearly how the failure of architectural criticism to respond to the richnesses of real life can have such a barbarising effect.

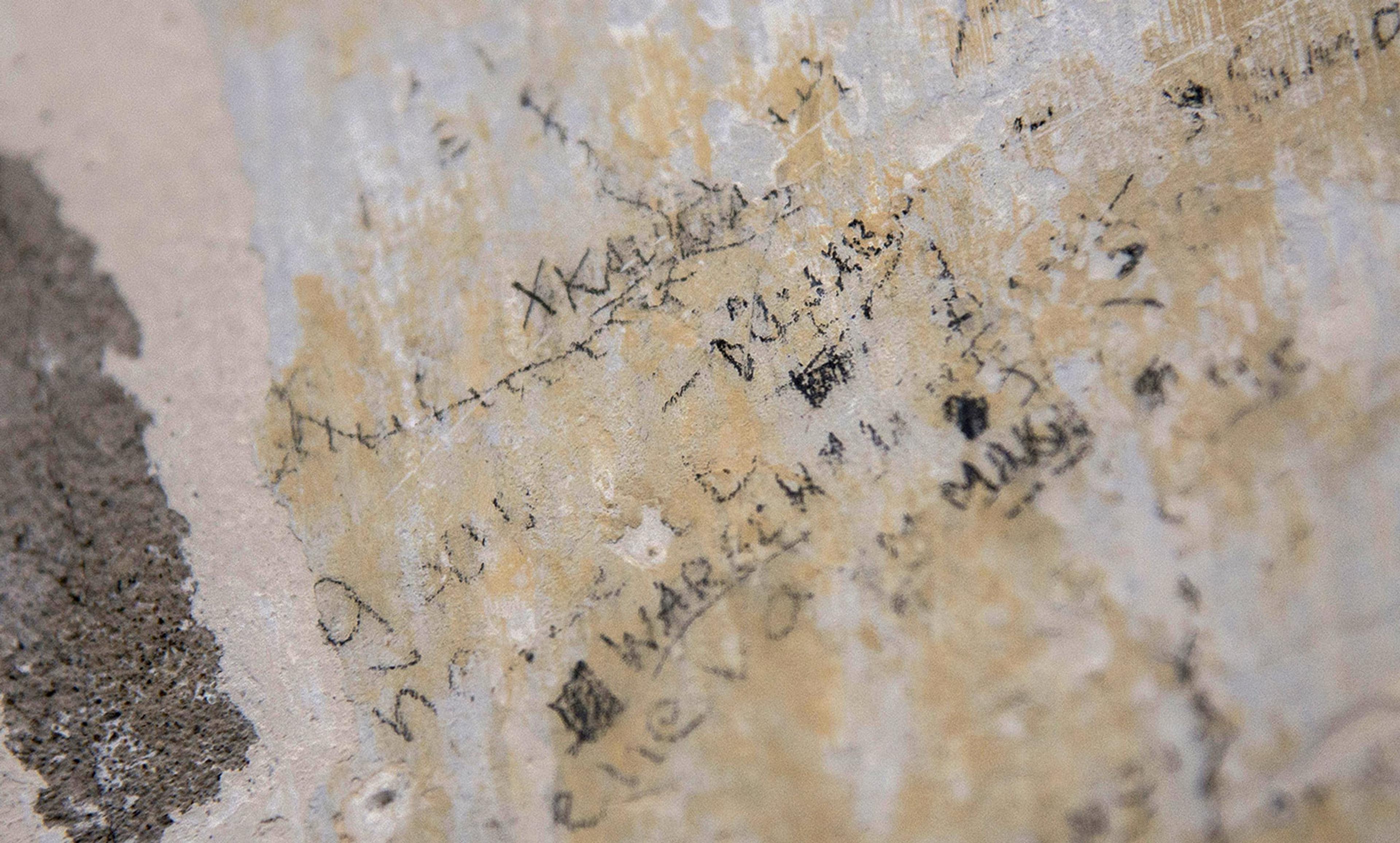

The point of postmodernism in architecture was that buildings were no longer supposed to be marching, bravely, proudly and teleologically, into the specific future envisaged by mid-century critics; that historical style and ornament were no longer beyond revival; that the greatness of buildings should not be primarily conceptual – instead, they should relate to everyday cultural experiences and engagements. Terry Farrell’s Comyn Ching redevelopment at Seven Dials near Covent Garden in London of 1978-1991, for example, was an extremely subtle weaving of historical motifs in layers at scales large and small across an old city block. But at the time, most critics found it impossible to describe it adequately. Because they could not read the future, they could not yet see how influential it was to be; and because there was nothing like it, and it did not fit into any established conceptual pattern, they had nothing to say. Instead, look at it, and describe what you actually see. This is not phenomenology: it is a search for real life.

Comyn Ching, in common with several others buildings by Farrell, is threatened by recent proposals for redevelopment, and as a result conservationists are now beginning to get their words together in order to try to save it. It has become a plausible task: we are well beyond the simplicities of 1980s architectural criticism. But we have a long way to go, and architectural writers have much to do if they are to explain not only why unusual buildings and landscapes, but also everyday ones, carry a value that is not easily described or ‘conceptualised’.

Historic buildings are under perpetual threat, even though they are large and expensive, and even though ours is a society generally more aware of waste and sustainability than ever before. Unless there is a common language, a demotic composed of many voices for buildings, it is very unlikely that the standard of design in most buildings will improve. And there is no need to look for a single reason why a building is important. It is more rewarding to hear the many and possibly conflicting voices of people who enjoy them, or have strong feelings about them, possibly even for reasons unconnected with their actual architecture.