CDC/ Melissa Dankel

During a TEDx talk in Calgary, Alberta last summer, the MIT doctoral student Steven Keating explained how curiosity about his brain led him to volunteer to have it scanned for a study. The result was diagnosis and eventual removal of a cancerous brain tumour. Keating was a convert. He has since amassed nearly 70GB of personal medical data, curated from hospital and doctor records, research labs, and direct-to-consumer medical testing, and insists that everyone could benefit from creating their own ‘medical selfies’.

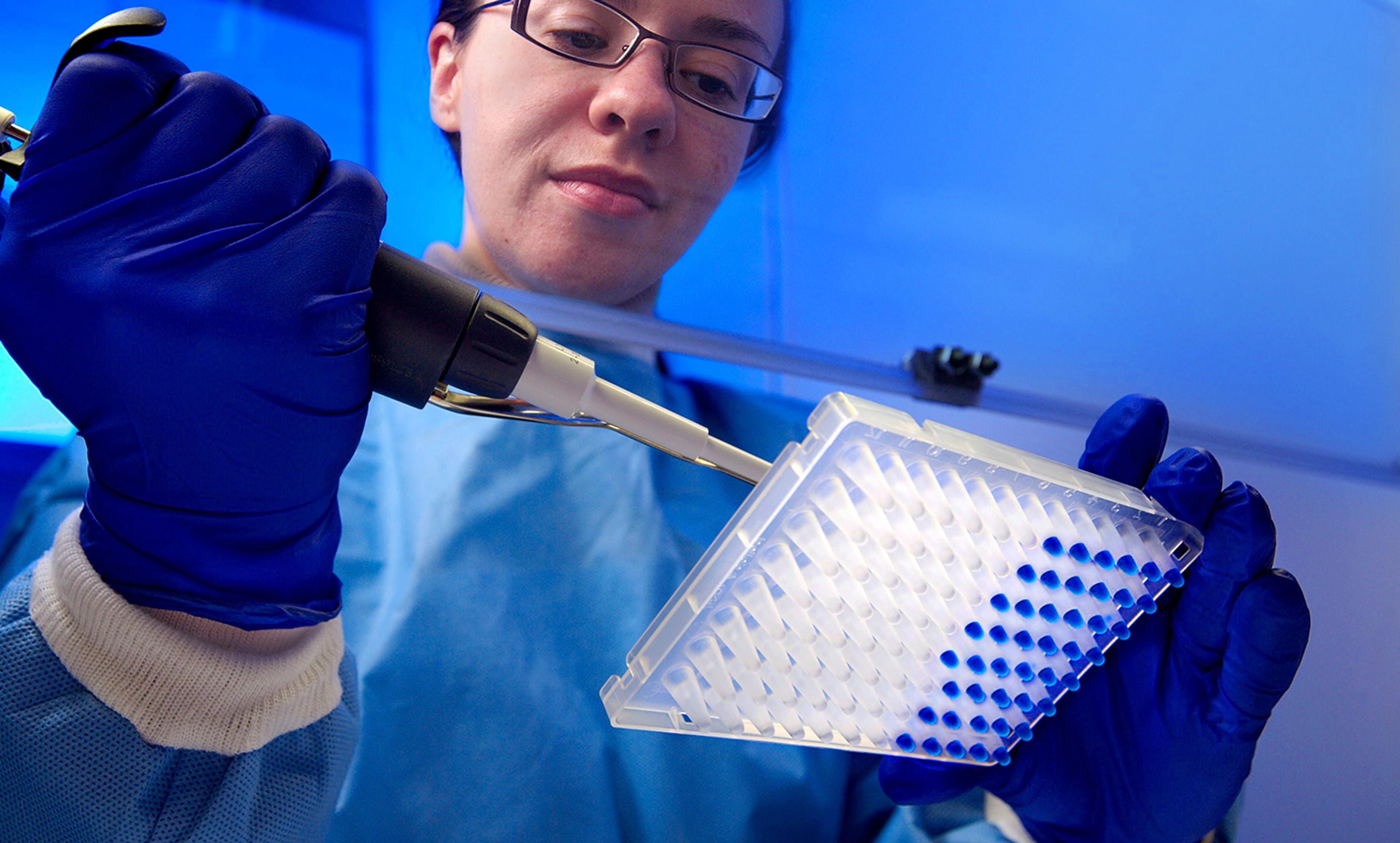

Thanks to a spate of new startups entering the healthcare realm, it’s never been easier to generate a snapshot of your personal health. Dozens of companies offer direct-to-consumer tests on saliva, urine, blood or cheek swabs that can indicate either the presence of or the genetic susceptibility to disorders ranging from diabetes to cancer. With the strike of a computer key, you can order a DNA testing kit to determine if you have increased vulnerability to any number of chronic diseases, to predict how you will respond to frequently prescribed medications, or to obtain diet, exercise and skincare regimens geared to your unique genetic makeup. You can even learn about the bacteria that have taken up residence inside your gut, and how they influence your health. Are these medical testing companies the new Ubers of healthcare, poised to disrupt the industry and usher in an age of patient-driven, on-demand medicine? In his 2015 book The Patient Will See You Now, the cardiologist Eric Topol predicts just such a medical revolution, in which newly empowered patients with smartphones will take charge of their own health care.

It’s no mystery why direct-to-consumer testing is so appealing: as the price of healthcare rises, consumers can’t help but think twice before running to the doctor for tests. On the other hand, the information you can request in the privacy of your home is unprecedented. Color Genomics will analyse a saliva sample for mutations on 19 genes known to affect risk for breast and ovarian cancer, including BRCA1 and BRCA2. Couples planning to have children could send their saliva to companies like 23andMe and Counsyl to learn if they are carriers for rare inherited diseases such as Tay-Sachs, cystic fibrosis, sickle-cell or Bloom syndrome. DNA4Life predicts how you will respond, based on your genetic makeup, to more than 120 commonly-prescribed medications. Dozens of companies offer genetic testing directly to consumers to provide information regarding nearly 400 diseases and traits.

Several home testing products currently under development promise even more. Cue’s elegantly designed ‘deep health tracker’ will use saliva, nasal swabs and blood to track levels of testosterone, inflammation, vitamin D, and fertility – and to detect influenza infection – and send results to your smartphone. Scanadu’s Scout, a scanning device modelled on the one used by Star Trek’s Dr Bones, will relay heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, blood oxygenation and respiratory rate to a smartphone app. QuickCheck Health, a self-described ‘clinic in a box’, is developing home tests for common ailments such as urinary tract infection and strep throat.

Meanwhile, consumers are able to send raw data from testing companies like 23andMe to interpretation websites such as LiveWello and Promethease. These companies will analyse information on thousands of different mutations, generating even more extensive health information related to health risks and other traits.

The rise in DIY medical testing has sparked concern among doctors and public health officials who fear that consumers might not understand the implications of test results, or could be unduly alarmed – or falsely reassured – by findings. But such concerns are not a reason to block consumers’ access to information about their own bodies: the benefits of individuals gaining deeper insight into factors that may influence their health outweigh the negatives, as long as they defer to the expertise of their doctors before acting on any test results. Doctors and genetic counsellors can contextualise genetic test information, for example, and advise consumers how to proceed in terms of screenings or treatment.

The geneticist Greg Lennon, a co-founder of SNPedia, which operates the Promethease system, concedes that disease risk based on genetic data alone is far from definitive. Environment and lifestyle play big roles as well, as do interplay between different genes.

But definitive or not, I would certainly want to know about anything that affected my future disease risk. Perhaps it would motivate me to be more conscientious about my screenings, or drive me to commit more fully to a healthier lifestyle. We all recognise that regular exercise, low-fat/high-fibre diets, and sufficient sleep are good for us – but knowing we harbour an increased vulnerability to disease might be the push we need to adhere to healthy regimens. ‘DNA is not destiny,’ says Lennon, ‘but what you learn from your DNA may provoke you to change your actions – and that changes your destiny.’