Detail from a portrait of Hugues Felicité Robert de Lamennais (1827) by Ary Scheffer. Courtesy Wikipedia

For most people today, socialism is associated with a secular or atheistic worldview. Since the October Revolution of 1917, most socialist regimes have built on Marxist doctrines, and taken clear anti-religious stances. From another perspective, however, secular or anti-religious socialism is exceptional, and religious socialism common. The vast majority of the socialist predecessors of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were acutely religious. Especially in France, socialists found religion integral to their political vision.

After the mid-19th century, socialists even became founders of new spiritualist occultist religious movements. The role of socialism as a secularising force in the 19th and 20th centuries was coincidental, and not inherent to socialism itself. In fact, socialists had a vital and productive relationship with religion. In the 1820s, the French Saint-Simonians, the first influential socialist movement, declared themselves the apostles of their ‘church’ and preached a ‘New Christianity’. The Fourierists, who succeeded the Saint-Simonians as the most dynamic socialist school, demanded the ‘return to the Christianity of Jesus Christ’. In the 1840s, the leading communist Étienne Cabet identified communism with ‘the true Christianity according to Jesus Christ’. Pierre Leroux, who had coined the term socialisme, explained its meaning with ‘religious democracy’. Engels, in 1843, had marvelled at the Frenchmen’s ‘mysticism’, but later observers, who had usually been shaped by Marxism, dismissed the religion of the early socialists as superficial rhetoric or childish enthusiasm. However, that is simply not the case. Many early socialists looked to religion for ways to define society according to principles both religious and socialist.

Early socialists sought to create a ‘synthesis’ of religion, science and philosophy to counter the excesses of the Enlightenment. They saw the Enlightenment, and the French Revolution, as needing correction against a tendency to materialism, atheism and egoistic individualism. The Saint-Simonians declared that ‘the political order will be, in its entirety, a religious institution’. In this perfect society, a class of priests would maintain social harmony. They even accepted the description of socialism as a ‘theocracy’, as long as one ‘understands theocracy as the state in which the political and the religious laws are identical, and where the leaders of society are those who speak in the name of God’.

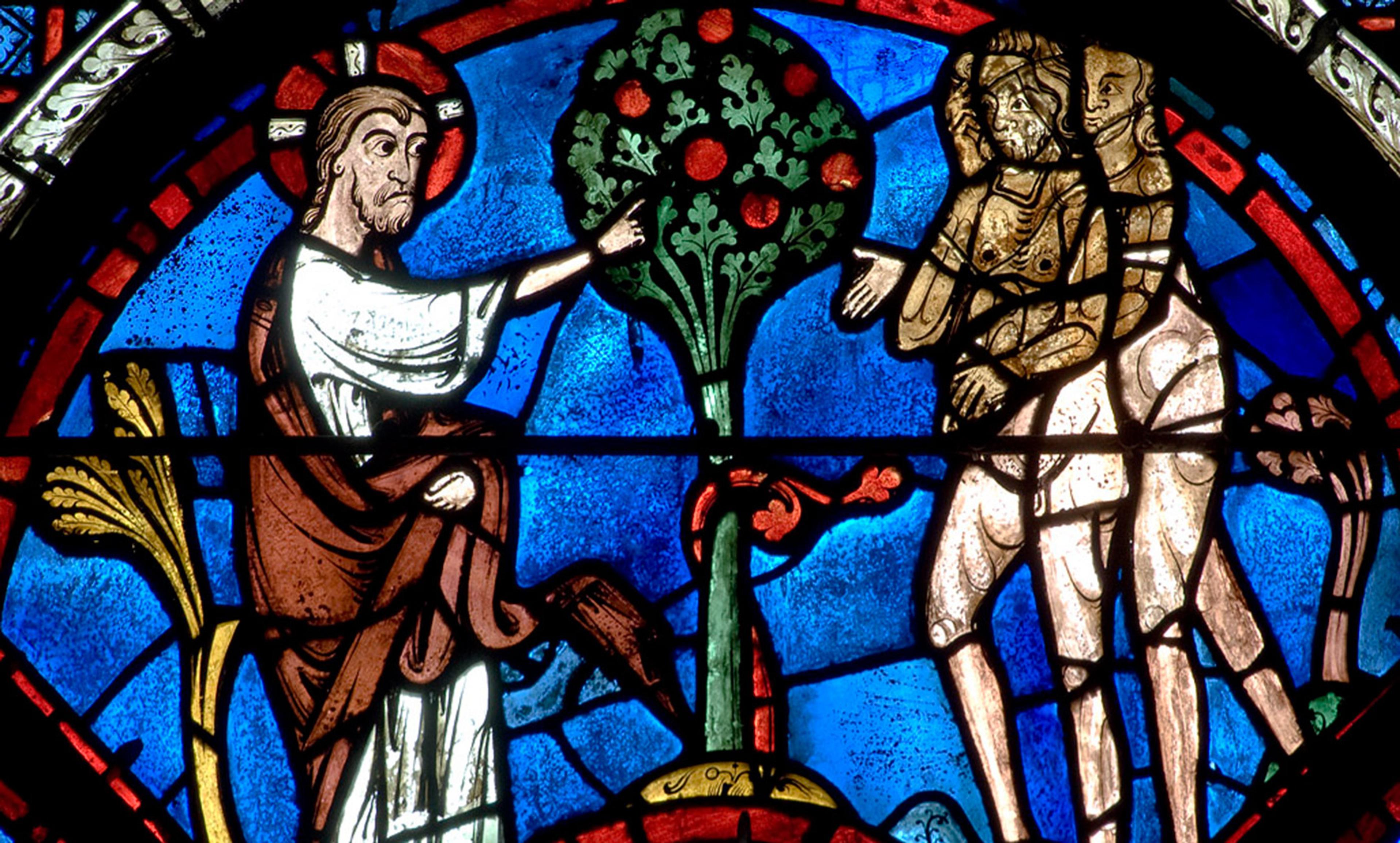

Following the long-established example of Catholicism, socialists demanded ‘spiritual authority’ and modelled their universal association after the structure of the Catholic Church. The borders to contemporary reformist Catholics were often blurred, most spectacularly in the case of Félicité de Lamennais, a priest who had founded the so-called neo-Catholic movement and had turned to a Christian socialism in the early 1830s. Lamennais’s highly influential writings fuelled the socialist determination to establish the ‘true Christianity’.

The February Revolution of 1848 failed to realise the socialist Kingdom of God on Earth. The coup of Louis-Napoléon in 1851 brought the demise of the Second Republic, and socialist activities were outlawed. It was in this atmosphere that the appearance of spiritualism caused a sensation. Spiritualism had emerged in the United States in 1848, when the Fox sisters claimed to be in contact with the spirits of the dead by so-called ‘rappings’. Since 1853, similar phenomena had caused a stir in France and Germany. Socialists, especially Fourierists, welcomed spiritualism, in part because it had emerged from US socialism and incorporated theories about universal harmonies and attractions, natural forces and spiritual regeneration conducive to socialism. In the 1850s, numerous socialist veterans became leading spiritualists.

At the same time, vehement debates about the future of socialism raged. The Revue philosophique et religieuse, an attempt to revive socialism in its July Monarchy vein, is an example of the clash between veteran socialists and their critics. The latter included the socialist Zionist Moses Hess. The fronts were clear: as a wrathful letter to the editor claims, the ‘scientific’ German socialism owned the future, while the failure of socialism in France owed to it being ‘theosophical socialism’.

Alphonse-Louis Constant, a clergyman who in the 1840s became notorious for his extreme radicalism, was another mystically inclined socialist. Born in 1810, he had abandoned his ecclesiastic career to enter the world of Romantic artists and socialists. Constant became a disciple of Lamennais and proclaimed a communisme néo-catholique. Like Saint-Simonians and Fourierists, he held that only an instructed elite could realise a peaceful revolution.

In his articles for the Revue, Constant maintained that he had found the key to achieving true socialism: the Kabbalah and its magical doctrines. Contemporaries were less surprised than later generations: historiographies of socialism – both critical and self-referential – regarded the socialists as the heirs of a heretical tradition that included mystics, theosophists, Kabbalists, magicians, Cathars, or Templars, and stretched back to the ancient Gnostics. Constant explained that this tradition represented true religion, and thus true socialism, but that its wisdom had been handed down in an encrypted form to save it from corruption. The decryption of this occult tradition would mean the emancipation of humanity.

Parallel to these articles, Constant began to adopt a pseudonym under which he would become famous as the founder of modern occultism: Eliphas Lévi. The first parts of his occultist Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (or Dogma and Ritual of High Magic), a work that is still influential, appeared in 1854. In this and his later books, Constant was the first author to propagate ‘occultism’. Its aim was the creation of a priestly elite of initiates that should lead the people to emancipation and, finally, establish a universal association with God where everybody is equal. The ‘universal science’ of magic, which Constant developed on the basis of contemporary socialist theories, was to play a central role. This would create the final synthesis of science and religion that would lay the foundations for the perfect social order, marking the last stage in the revolutionary march of human progress.

The language of magic should not obscure Constant’s ideas as a socialist. Scholars have sometimes regarded his call for spiritual authority, theocratical hierarchy and the gradual instruction of the ‘ignorant masses’ as a reactionary political turn. In fact, these were church-inspired socialist doctrines. Because of the dominance of materialist, atheist varieties of socialism since the second half of the 19th century, the relationship between religion and socialism has been in some profound ways distorted. Not only did religion lead many to socialism; with spiritualism and occultism, socialism has contributed in lasting ways to the landscape of modern religion.