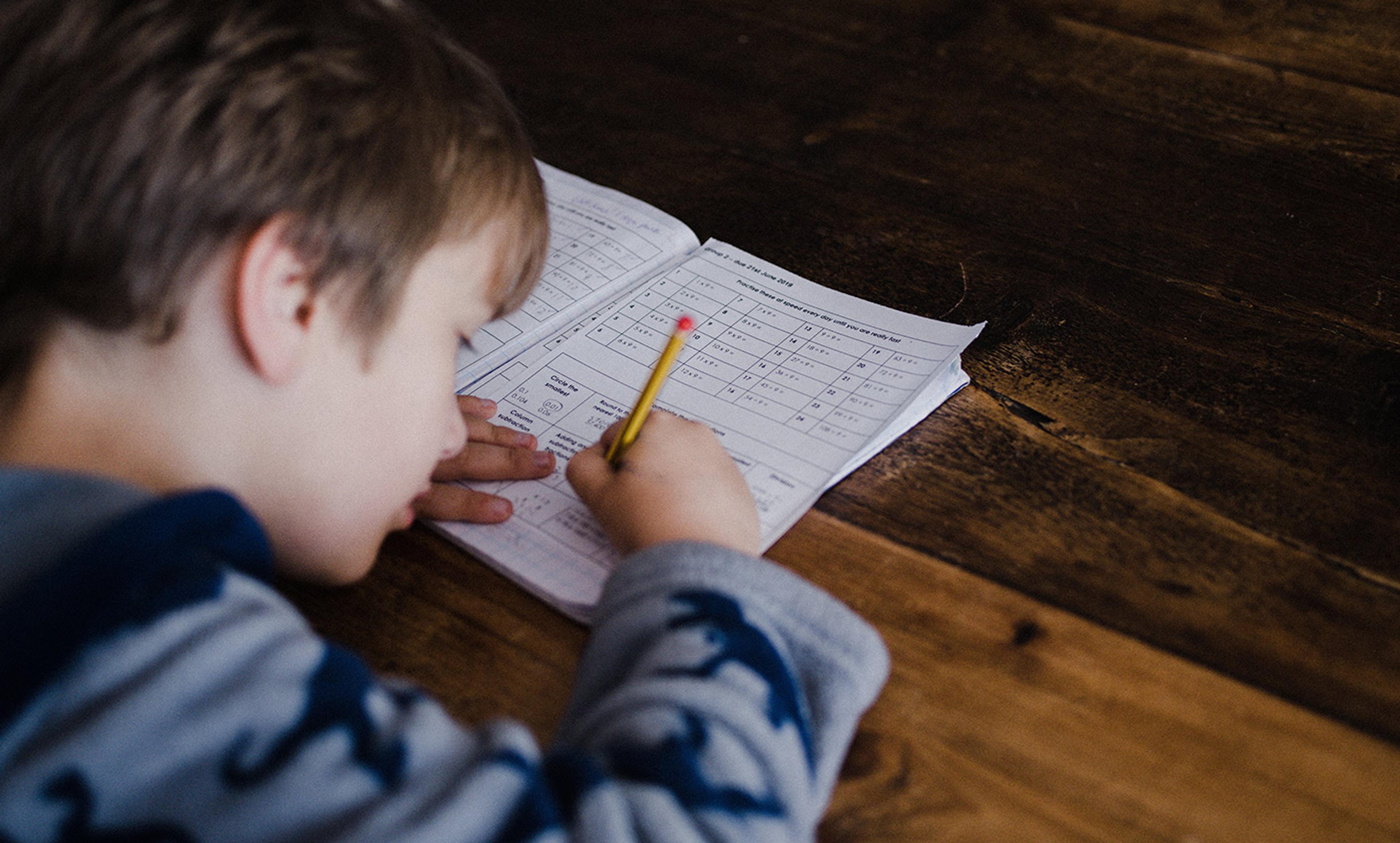

Boy Scouts at Gettysburg, 1913. Courtesy Library of Congress

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA) has both proud supporters and critics of its policies on religious beliefs and sexuality. But for more than a century, the organisation has performed a distinct and vital social function. The BSA and other youth-camping associations developed in the early 20th century. They came to exist primarily as a response to the decline in employment and job apprenticeships among young teens, and the growing disconnection between these youths and the larger adult community and its civic responsibilities.

Newly compulsory schools and voluntary organisations created segregated spaces in which young people could socialise away from the city streets and political life. Historians have argued that, in the United States, Boy Scouting and other youth summer camps taught members primitive virility, militarism, frontier nostalgia and physical aggressiveness as an antidote and escape from a rapidly urbanising and industrialising society. However, my own historical research and previous work experiences suggest that both Boy Scouting and many residential summer camps teach essential life skills – such as a cooperative work ethic and active civic engagement – that job apprenticeships and cross-generational public interaction once provided to our nation’s youth.

In the 1910s and ’20s, Scout leaders carefully developed independence and self-reliance in boys growing up in an increasingly sheltered society. Removed from parents’ and teachers’ close supervision at home and at school, early Boy Scouts learned to keep track of their own belongings and hygiene. They cooked for themselves over an open fire. Perhaps most importantly, they learned to make their own trail through the camp forests as well as what leaders referred to as the bewildering ‘mental woods’ of modern adolescence. With guidance from early troop leaders, boys could try out more adult behaviours and personalities. They learned to pull their own weight and become helpful, trustworthy citizens. Each had to contribute labour and willing cooperation to guarantee the smooth functioning of the miniature community that his camp cabin or Scout troop represented. Early Scouts learned such skills as studying nature scientifically, performing First Aid and emergency rescues, cooperating with a group on set standards of progress, and conserving resources efficiently. Instead of rejecting modern society, early Scout leaders combined certain 19th-century ‘male’ traits such as a hard work ethic and modesty with newer virtues such as scientific efficiency, expert management, and practical but non-partisan civic responsibility.

I was initially drawn to the study of early Boy Scouting by my experience as a cabin counsellor and horseback-riding instructor at a rustic Tennessee summer camp for boys and girls. I did it for nine years. Like most veterans of summer-camp work, I came to a moment that nearly all college-aged camp counsellors reach: leave and move on to new work, or dive fully into summer-camp work as a career, aiming to become a camp director. Instead, I hedged my bets by applying for graduate programmes in US history while enjoying another summer as a counsellor.

Nearly 20 years after I moved into studying boyhood, my book Modern Manhood and the Boy Scouts of America (2016) was published. It’s in part an answer to the questions that began to preoccupy me as a camp counsellor. I was especially intrigued by the contrasts and similarities between the boys’ and girls’ sessions at my camp. Girl and boy campers came for separate sessions, in different weeks, and each year a handful of the guy counsellors served as support staff for the girls’ camp in specialised activity areas such as horsemanship and the lakefront. Working both sessions allowed me and other full-summer employees to witness the differences between boys’ and girls’ camp.

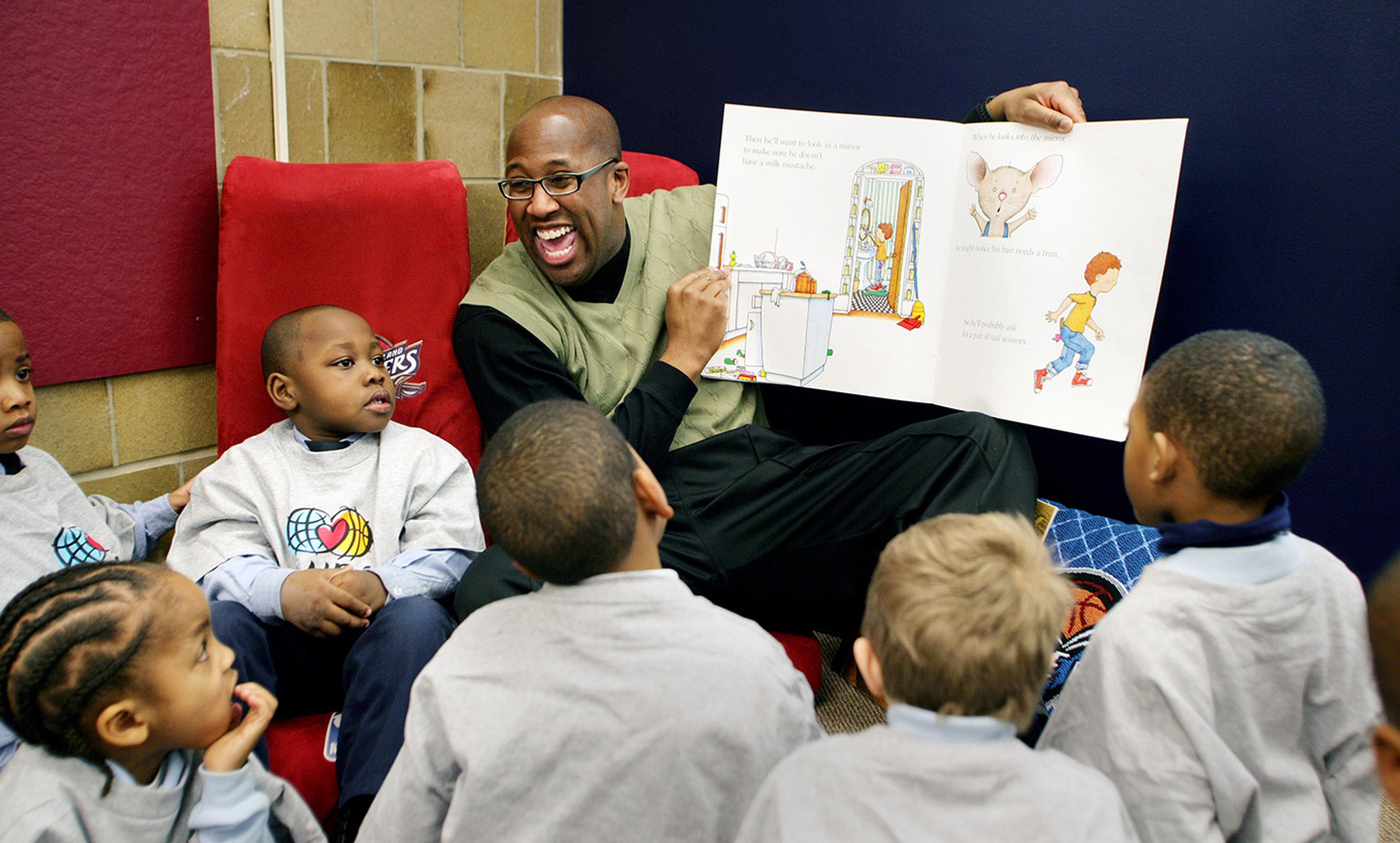

Constant physical activity characterised the boys’ camp. It mediated their friendships and nearly all their experiences. Girl campers, on the other hand, typically built camaraderie through conversation and song. At the same time, both the boys and the girls as well as their respective counsellors shared a way of speaking about camp as the ‘real world’, contrasting the other weeks of the year with camp as the ‘outside’ world. Both sessions taught campers structured independence within a small group, cooperation with others, community involvement, and careful use of resources. Like many other residential summer camps over the past century, my camp emulated US Boy Scout teachings from the 1910s and ’20s that used natural environments and small groups to encourage youths to grow into adult roles.

But many children in the US today experience summer day camps, after-school programmes and sport leagues in segmented periods that lack an overarching vision of proper adolescent development. In my own city of Memphis, there are signs of innovation such as elementary-school gardens that incorporate local adults and the ‘REAL Places’ middle-school curriculum (an acronym for students ‘recognising environmental assets and liabilities’ in their own neighbourhoods). These are important efforts to re-bridge the century of division between the worlds of children and adults, but still more needs to be done to match the potential for youth maturation and civic engagement in the residential summer camp or the early Boy Scout troop.