Aleksandr Zykov/Flickr

‘What’s the magic word?’ Any English-speaking toddler knows the answer to this question: ‘please’. And any student of French, German, or another modern European language can be just as sure of learning that language’s equivalent of ‘please’ in the first lesson. The word is now considered essential for normal interaction between civilised people, and those who fail to employ it are seen as rude.

Politeness, though, has not always worked this way. Ancient Greeks of the fifth century BCE had no word for ‘please’, that is, no polite expression that they regularly attached to requests. When making requests of people they liked and respected, people they did not want to offend, these Greeks normally used a simple command, such as ‘Give it to me!’, ‘Go!’, or ‘Sing!’. Such commands were not rude in that culture, for rudeness is as culturally relative as politeness. In some cultures, it is rude to begin eating without wishing the other diners at your table a pleasant meal; in other cultures it is not. In some cultures, it is rude to accept food the first time it is offered; in other cultures it is not. And while in many cultures it is rude to use a simple command instead of saying ‘please’, in classical Greek culture it was not.

‘Please’ is by no means the politest way of making requests in English: compare ‘Please pass the salt’ to ‘Is there any chance you could help me with this computer problem? Pretty please with sugar on it?’ Politeness has degrees, and in most cultures you need to use more of it in some circumstances than in others. Minor requests made to close friends and family typically need less in the way of polite periphrases than onerous requests made to more distant associates: picture the difference between the way you might ask a good friend to lend you a pencil and the way you might ask a distant acquaintance to let you borrow a valuable book.

To this rule, the classical Greeks were no exception. When making the kind of major requests that in English would call for more than a simple ‘please’, they too used polite periphrases rather than simple commands. A man asking for substantial instruction says, ‘I would gladly learn from you’ rather than just ‘Teach me!’, while a child asking his grandfather for a big present says, ‘I entreat you to give it to me’ rather than ‘Give it to me!’ So the Greeks clearly shared some of our ideas about how to ask for something politely, as well as our ideas about when extra politeness is required. Yet they did not share our idea that some sort of polite word should usually be attached to requests: only 12 per cent of the requests in classical Greek literature use one of these polite periphrases (a fact not always evident in English translations, since translators frequently add ‘please’ to passages that do not contain it in the Greek).

But all this changed in the third century BCE. Suddenly, Greek speakers stopped using unadorned commands as their default way of making requests. Commands were still used to social inferiors, but polite formulae like our ‘please’ were regularly used to equals and superiors. What prompted Greek speakers to start saying ‘please’?

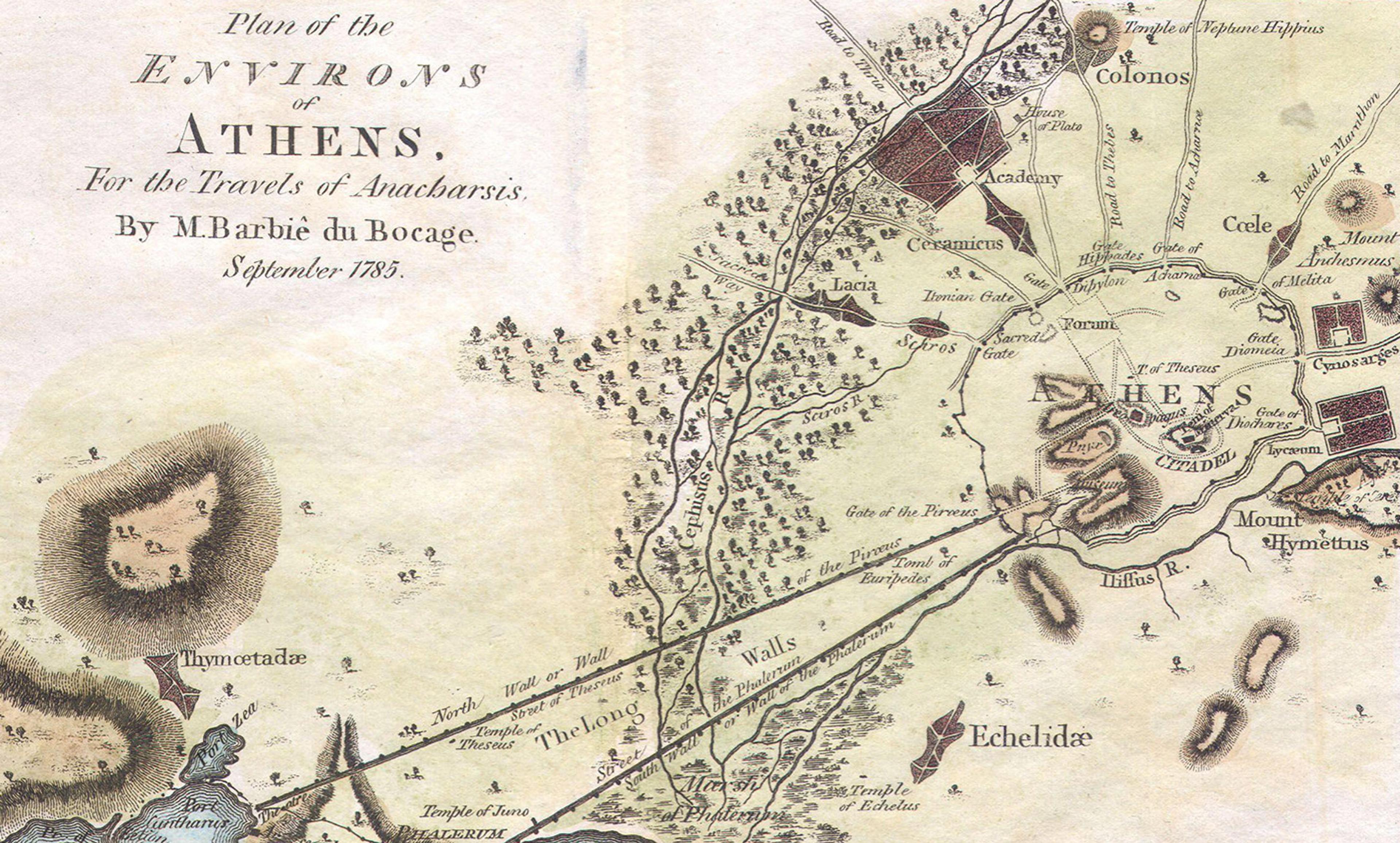

The answer lies in a change of culture. Classical Greece (or at least the portions of it from which most of our surviving literature comes, particularly Athens) was fiercely egalitarian and democratic. Neither the equality nor the democracy extended to everyone – women and slaves formed two major classes of exceptions – but those who had the good fortune to be included valued their equality highly and made sure it was maintained. Men who revealed greater-than-average wealth were quickly relieved of the excess by being assigned to fund an artistic or military enterprise, and those who thought themselves better than the rest were often sent into exile. This egalitarian culture was reflected in the classical Greek language, in which adult male citizens addressed each other all in the same way – and made requests without saying ‘please’.

This situation came to an abrupt end in the late fourth century BCE, when Greece was conquered by the Macedonian king, Philip II. Philip, his son Alexander the Great, and their successors enormously expanded the number of Greek speakers by making Greek the language of government and elite culture all over the Eastern Mediterranean. Greek speakers of the third century BCE were no more likely to live in Greece itself (as opposed to Egypt, Turkey, or the Middle East) than modern English speakers are to live in England, rather than in America, Canada, Australia, etc. But the Greek culture spread by Macedonian conquests lacked the element of democracy and equality, for it was attached to a hierarchical social system: not only a king and group of Macedonian nobles at the top, but below them a highly stratified society, often one surviving from the pre-Macedonian social structure of the conquered areas.

In fact, third-century Greek speakers had as much chance of living in an equality-loving democratic society as modern English speakers have of living in a communist state. Instead they lived in kingdoms composed of powerful nobility, disempowered peasants, and many levels in between. It was this shift that caused Greek speakers to start saying ‘please’ to everyone except their inferiors: third-century Greek reflected the society that used it just as fifth-century Greek had reflected its own society.

Our own society is far more egalitarian than Alexander the Great’s empire, but far less egalitarian than classical Greece. Some people are richer and more important than others, and they are not afraid to show that. This inequality is reflected in our language, for ‘please’ is not always used with requests. The same parents who insist that their children use ‘please’ to request a cup of juice are happy to omit ‘please’ themselves when ordering those children to put on their coats and shoes. Indeed, the reason ‘please’ is so important is that its use is far from universal: every day we hear both polite requests with ‘please’ and commands without it. If the ‘magic word’ were attached to all requests and all commands, it would cease to be polite, in the same way the pronoun ‘you’, originally a plural used as a polite singular like French ‘vous’, ceased to be polite when its less polite alternative ‘thou’ disappeared entirely.

These historical examples suggest that certain types of politeness may be inextricably connected to inequality. Yet we now value both equality and politeness highly: are they compatible? They may not be. If we ever achieve the fully equal society that we at least claim to want, perhaps we shall all give up saying ‘please’.