The last emperor, Sapa Inka Atahualpa. Courtesy Wikipedia

Between the 1430s and the arrival of the Spanish in 1532, the Inkas conquered and ruled an empire stretching for 4,000 kilometres along the spine of the Andes, from Quito in modern Ecuador to Santiago in Chile. Known to its conquerors as Tahuantinsuyu – ‘the land of four parts’ – it contained around 11 million people from some 80 different ethnic groups, each with its own dialect, deities and traditions. The Inkas themselves, the ruling elite, comprised no more than about one per cent.

Almost every aspect of life in Tahuantinsuyu – work, marriage, commodity exchange, dress – was regulated, and around 30 per cent of all the empire’s inhabitants were forcibly relocated, some to work on state economic projects, some to break up centres of resistance. Despite the challenges presented by such a vertical landscape, an impressive network of roads and bridges was also maintained, ensuring the regular collection of tribute in the capacious storehouses built at intervals along the main highways. These resources were then redistributed as military, religious or political needs dictated.

All this suggests that the Sapa Inka (emperor) governed Tahuantinsuyu both efficiently and profitably. What’s more, he did so without alphabetic writing, for the Inkas never invented this. Had they been left to work out their own destiny, this state of affairs might well have continued for decades or even centuries, but their misfortune was to find themselves confronted by both superior weaponry and, crucially, a culture that was imbued with literacy. As a result, not only was their empire destroyed, but their culture and religion were submerged.

Instead of writing, the Inkas’ principal bureaucratic tool was the khipu. A khipu consists of a number of strings or cords, either cotton or wool, systematically punctuated with knots, hanging from a master cord or length of wood; pendant cords might also have subsidiary cords. The basis of khipu accounting practice was the decimal system, achieved by tying knots with between one and nine loops to represent single numerals, then adding elaborations to designate 10s, 100s or 1,000s. By varying the length, width, colour and number of the pendant cords, and tying knots of differing size and type to differentiate data, the Inkas turned the khipu into a remarkably versatile device for recording, checking and preserving information.

The main uses to which khipus were put were, firstly, to record births, deaths and movements of people, thereby providing an annual census upon which local labour, military and redistributive assessments could be made. They were also used to count commodities, especially the tribute payable by conquered provinces such as maize, llamas and cloth (there was no coinage). Maize, for example, might be represented by a yellow cord, llamas by a white cord, and so on. Early Spanish chroniclers and administrators were astonished at the accuracy of khipu calculations: according to Pedro de Cieza de León, writing in the late 1540s, they were ‘so exact that not even a pair of sandals was missing’.

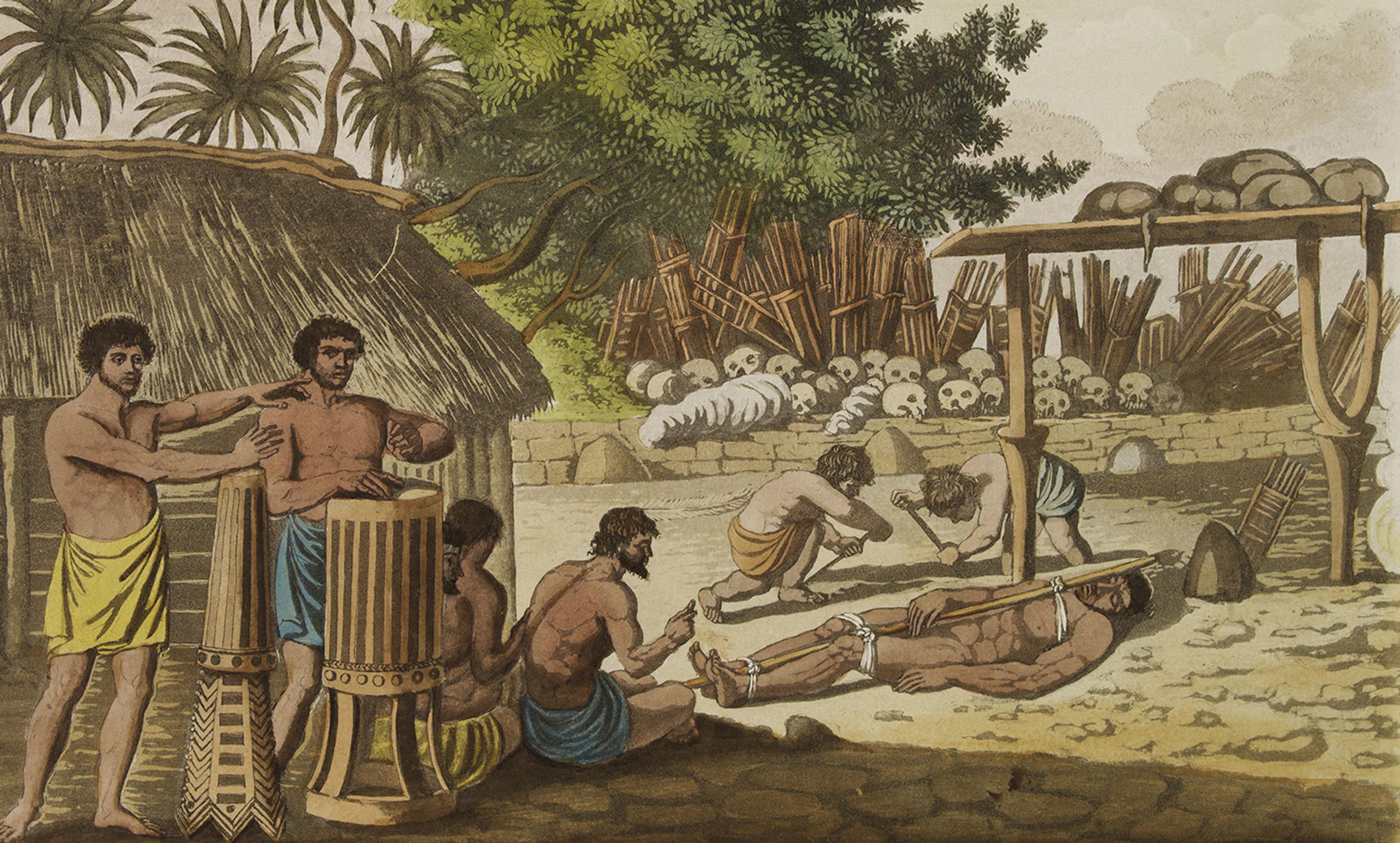

Training in what anthropologists call ‘khipu literacy’ was compulsory for a specified number of incipient bureaucrats (khipukamayuqs) from each province. For this, they were sent to Cusco, where they also learned the Inka dialect, Quechua, and were schooled in Inka religion. Like most imperial rulers, the Inkas conquered in the name of an ideology, the worship of their chief deity, the Sun, and his child on Earth, the Sapa Inka. Sun-worship was mandatory throughout the empire, and vast resources were allocated to the performance of an annual cycle of festivals and rituals, and to the maintenance of the priests who staffed Tahuantinsuyu’s ubiquitous shrines. However, the Inkas also tolerated local deities, which, if perceived to be efficacious, might be incorporated into the Inka pantheon.

It is hard to see how alphabetic writing would have helped the Inkas to administer Tahuantinsuyu more efficiently: this was not an intensively governed empire but a federation of tribute-paying and politically allegiant provinces. In other spheres of government, such as law, writing would doubtless have made more of a difference, leading perhaps to the development of written law-codes, arguably even a ‘constitution’. But since writing was never developed, imperial rule remained weakly institutionalised, leading to a concentration of power and office, which meant that when the Sapa Inka was removed, there was little to fall back on.

So when Francisco Pizarro and his 200 or so conquistadores captured the Sapa Inka Atahualpa at Cajamarca on 16 November 1532, Tahuantinsuyu was left headless and disorientated. The confusion that followed was the crucible in which Spain’s New World empire was forged.

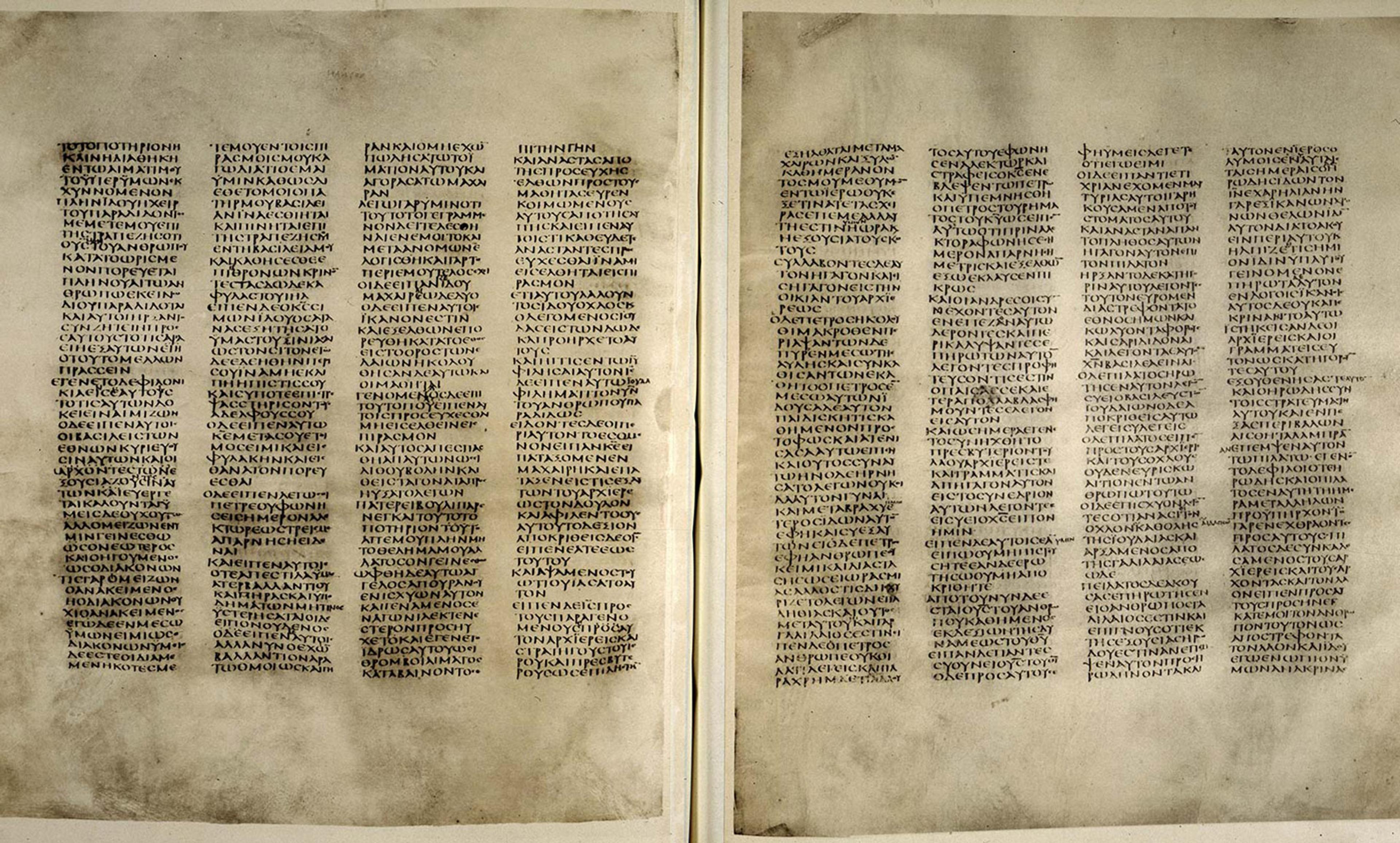

The seizure of Atahualpa was preceded by an incident pregnant with significance for the creation of European empires on a global scale. The first Spaniard to approach him after he entered the great plaza at Cajamarca was the Dominican friar Vicente de Valverde, carrying a cross in one hand and a missal in the other. Speaking through an interpreter, he declared that he had come to reveal to Atahualpa the requirements of the Catholic religion, which were contained in the book he was carrying. Atahualpa demanded to see the missal. When handed it, he was initially unable to open it. When he eventually managed to do so, he seemed more impressed by the calligraphy of the text than what it said. After examining it for a while, he angrily hurled it to the ground. This act of blasphemy was the trigger for Pizarro to give the order to attack.

After eight months of captivity, Atahualpa was tried for treason and condemned to death. If he converted to Christianity, he would be garrotted; if not, he would be burned (as a heretic). Since fire would destroy his body, he agreed to accept conversion, and towards nightfall on 26 July 1533 he was led out into the plaza at Cajamarca, tied to a stake and strangled. The last words he heard were those of Friar Valverde instructing him in the articles of the Catholic faith. Atahualpa wanted to preserve his body so that it could be mummified and venerated by his descendants.

Whatever he believed his ‘conversion’ to imply, it was clearly not the monotheism central to Catholic doctrine. Inka religion, which was broadly speaking animistic, acknowledged many gods, ranging from heavenly bodies (Sun, Moon, stars) to topographical features (mountains, rivers, springs) to ancestors, whose earthly remains were venerated to a degree that baffled Europeans – although most of them made little attempt to understand such practices, disparaging them as heathen, folk-magic or simply childish.

Like other Religions of the Book, Catholicism demanded strict adherence to one God, and the rejection of all other deities. Religions based upon books such as the Bible or the Quran, being (literally) prescriptive, were less tolerant than oral religions. Rival belief-systems presented both an opportunity and a threat. Missionaries and evangelists preached conversion, but with them came inquisitors or crusaders, at which point definitions were sharpened, and criteria for inclusion and exclusion delineated. ‘Truth’ acquired a different meaning, less something to be sought after than something to be received: one God, one credo, one book (‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me’). ‘Reform’ for a book-centred religion did not mean adaptation, but a reversion to fundamentals – the immutable ‘word of God’, as interpreted by the priesthood. Confronted by such certainties, backed by coercive force, the more open-ended, absorbent oral religions of Africa or the Americas were simply overwhelmed.

Nor was this only a matter of religion. The greater ‘law-worthiness’ given to written evidence by literate incomers meant, for example, that customary land-rights and inheritance patterns were similarly overridden. Despite also being colonised by Europeans, societies with written cultures in China, India and the Middle East proved much more resistant to European cultural hegemony than oral societies. The strenuous efforts made in recent times to recover and promote the indigenous heritage of the Americas, Australasia and Africa are testimony in themselves to the degree to which those cultures were submerged, suppressed or derided by Europeans. Their lack of a written tradition was at least partly responsible for this.