MCC Current/Flickr

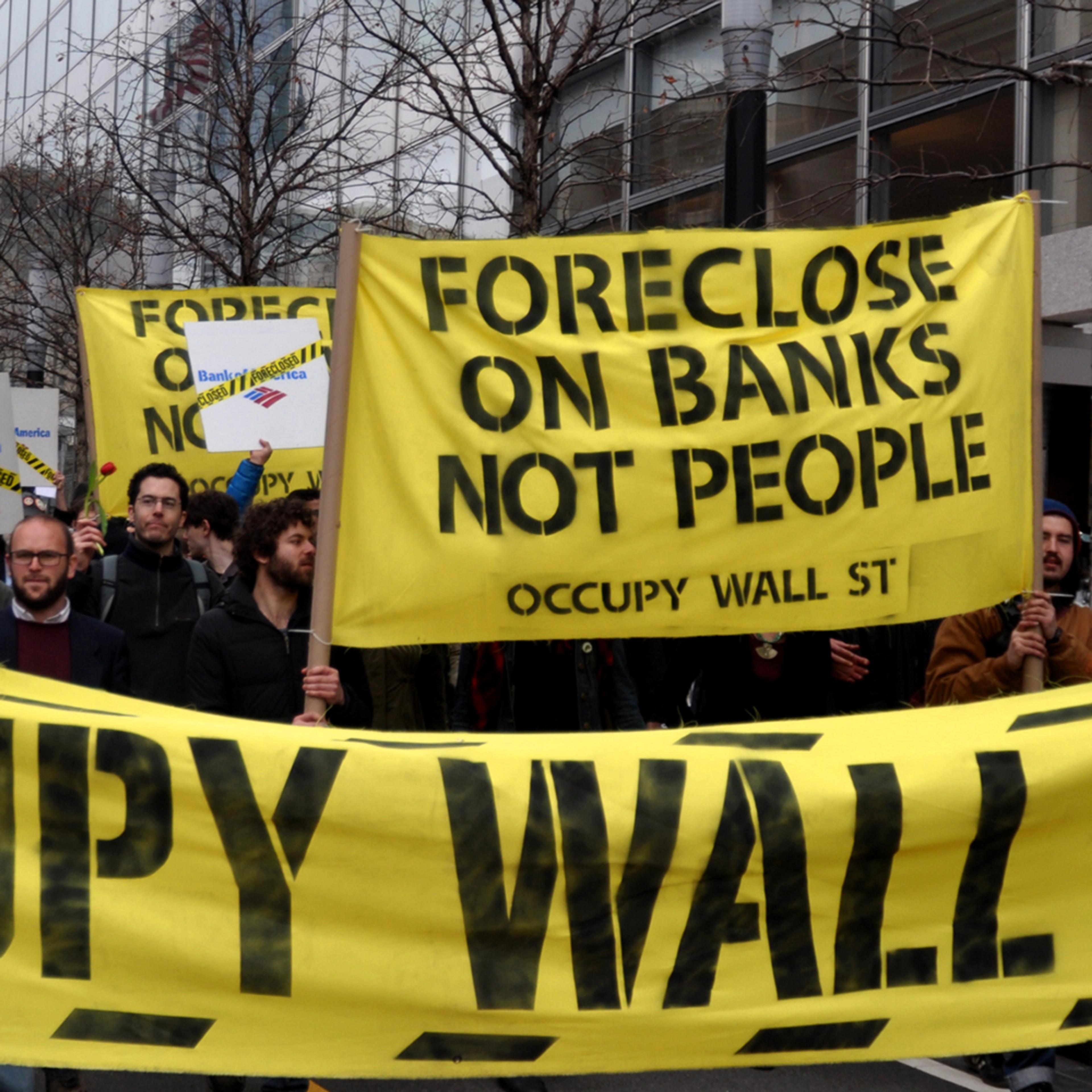

In June 1962, 59 student activists met in Port Huron, Michigan to draft a manifesto of their core principles. They condemned racism in the United States and the nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union. Most of all, though, they indicted their own institution, the modern US university, for ignoring and suppressing their voice. Students needed to ‘wrest control of the educational process from the administrative bureaucracy’, The Port Huron Statement declared. Otherwise, the empty suits who ran the university would drown its emancipatory potential in a sea of bland rituals and senseless rules.

We heard echoes of these sentiments in the protests that seized US campuses last November. Like their forebears in the 1960s, today’s students blasted university leaders as slick mouthpieces who cared more about their reputations than about the people in their charge. But unlike their predecessors, these protesters demand more administrative control over university affairs, not less. That’s a childlike position. It’s time for them to take control of their future, instead of waiting for administrators to shape it.

Most of the protests last fall focused on racism at the universities themselves, rather than in US society generally. Nearly every formal demand issued by the students included a request for a new university office, rule or regulation. Administrators typically complied, too, marking yet another departure from the 1960s. Back then, university officials regarded student protesters as an existential threat to the university itself. Today’s administrators embraced the protesters, promising to ‘do better’ – and, not incidentally, to provide more administrators. Some schools pledged to hire ‘Chief Diversity Officers’; others agreed to institute new diversity training and programming; still others announced new multicultural and counselling centres, aimed especially at assisting minority students.

What’s going on here? At the simplest level, the protests over race and diversity reflected the increase in diversity across US higher education. The number of black college students tripled between 1976 and 2012, when African Americans went from 10 per cent to 14 per cent of the undergraduate population. Hispanic enrolment rose even more sharply, from just 3 per cent in 1976 to 14 per cent – the same fraction as African Americans – in 2012. To be sure, vast racial inequalities remain: although minorities represent a third of all college students, for example, they make up about one-seventh of students at selective private and public colleges. But these schools also compete fiercely for the most qualified minority students, which reflects another huge difference from the past. Indeed, among elite institutions, diversity has become a key emblem of elite status. So in one sense, universities were a victim of their own success. Attracting a critical mass of minority students, they faced new demands from that same clientele.

These years also witnessed a dramatic shift in patterns of university employment, away from faculty and towards administrators. In 1975, universities had almost twice as many professors as administrators; 40 years later, the administrators outnumber the faculty. Over this span, the number of ‘executive, administrative, and managerial employees’ at universities rose by 85 per cent; meanwhile, so-called ‘professional staff’ – accountants, counsellors, and so on – ballooned by an astonishing 240 per cent. Part of the reason lay in the perverse economic competition between different schools, which offered a host of new student services and amenities in order to attract more paying customers. There was also a growing maze of federal and state regulations, which required new teams of officers to ensure compliance. Consider the recently promulgated federal instructions under Title IX of the US education code, which requires universities to establish systems for preventing and punishing sexual assault. That in turn forces them to hire dozens of counsellors and investigators, lest the universities run afoul of the new rules.

As universities layered on more and more bureaucracy, students came to believe that every campus problem had a bureaucratic solution. Officials are expected to remove every trace of racism, ranging from outright bigotry to smaller ‘microaggressions’; examples include asking a minority student if she is from ‘the ghetto’, or whether she was admitted to school under affirmative action. Protesters in November demanded that universities institute penalties for these types of comments, like mandatory diversity training for miscreants. Never mind that regulations of campus speech have been found unconstitutional by every court that has addressed them, or that most studies of diversity training have failed to show that it improves race relations. Symbolically, at least, adding a new rule or requirement will show that the university is ‘doing something’. And when it falls short, as it inevitably must, it will be asked to do more.

How can we break this cycle of administrative demand and dashed expectation? We might start by encouraging students to revive older traditions of direct action, which would leverage their own power instead of ceding yet more of it to university officials. If you’re the target of racial slights or insults, don’t wait for your school to institute yet another speech code or diversity training: organise your own teach-ins and rallies, where students can enlighten each other. If sexual assault is rife on campus, don’t rely on administrators to eliminate it: stage protests outside dormitories and fraternity houses, reminding everyone what goes on inside of them. If the school newspaper prints an article that offends you, don’t tell the university to de-fund the paper: publish your own online blogs and journals, and circulate them far and wide.

Asking administrators to solve every problem infantilises students, even as it contributes to the top-heavy bloat of our universities. Our students need to grow up, in the most political way, by wresting control of the educational process from an administrative bureaucracy that wields way too much authority already.